-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

As a power system specialist who spends a lot of time inside pharmaceutical plants, I tend to look at flow meters the same way I look at UPS systems and inverters: they are quiet infrastructure that only gets noticed when something goes wrong. Yet just as a poorly maintained UPS can bring a critical line down, a misapplied or drifting flow meter can degrade product quality, trigger deviations, and quietly waste hundreds of thousands of dollars in gases, solvents, and energy.

Pharmaceutical production has become one of the most demanding environments for flow measurement. From sterile water and high-value APIs to nitrogen, compressed air, and aggressive cleaning solutions, engineers must measure fluids precisely, repeatedly, and in a way that stands up to regulators and validation teams. Modern flow meter platforms from major suppliers, including those you would source from Yokogawa, are built around a set of proven measurement principles. Understanding those principles and how they behave in real pharma processes is the starting point for specifying the right instruments, designing reliable systems, and keeping the plant in a safe operating window.

In this article, I will draw on published application notes and technical guides from manufacturers and solution providers in flow measurement and pharma utilities to unpack how high-performance flow metering supports pharmaceutical manufacturing, and how to think about selection, application, and ongoing reliability.

At its core, a flow meter is an instrument that measures how much fluid passes a point per unit time. That fluid may be a liquid, gas, vapor, or even a slurry. Technical sources define flow in either volume per unit time or mass per unit time. Volume flow is typically used when density does not change much, such as many liquids, while mass flow is preferred for gases and steam where density varies strongly with temperature and pressure.

In pharmaceuticals, this seemingly simple measurement underpins almost every critical step. Research from BCST Group, Burak, and others highlights three big reasons accurate flow measurement is treated as a foundational control function rather than a convenience.

First, it is essential for product quality and batch consistency. Pharmaceutical manufacturing recipes are built around precise ratios of active ingredients and excipients. Flow meters are used to control the flow of raw materials into reactors, blending tanks, and continuous lines so that each batch follows the defined formulation. Inadequate control or undetected drift in flows can shift reaction stoichiometry, change coating thickness on tablets, or alter solvent ratios, all of which show up as batch variability.

Second, accurate flow measurement is directly tied to patient safety. As summarized in technical commentary on parenteral products, flow accuracy affects the actual delivered dose in injections and infusions. Underdosing risks inefficacy; overdosing can create serious adverse events. Even when the flow meter is upstream of final filling, any systematic bias in mass or volume dosing can carry through to the final product.

Third, regulators expect robust measurement and control. Agencies such as the FDA and EMA require manufacturers to demonstrate that critical process parameters, including flows of gases and liquids, are measured, controlled, and documented. Articles on pharmaceutical flow measurement emphasize that failure to do so can lead to observations, rework, and, in worse cases, recalls.

On top of the quality and compliance issues, there is a hard financial edge. Flow meters are one of the few tools that tell you whether your expensive nitrogen, compressed air, solvents, and purified water are being used efficiently. Studies on compressed gas and utility monitoring show that poor flow measurement drives unchecked leaks, excessive purging, and oversized equipment, all of which hit operating costs.

Before picking a meter type, it helps to be clear on what quantity you actually care about. Technical primers on mass flow technology and flow meter selection emphasize a few core concepts.

Mass flow rate quantifies the amount of mass moving per unit time. Industry references often express this in grams per minute or pounds per hour. Mass does not change if pressure or temperature changes, which makes it a solid basis for controlling how much chemical, gas, or API you are really moving.

Volume flow rate measures the volume per unit time, such as gallons per minute. For liquids whose density is relatively constant in your operating window, volume is a convenient proxy. For gases and steam, volume changes as pressure and temperature change, so volume alone can mislead you unless it is corrected or standardized.

Mass flow meters measure mass directly using thermal dispersion or Coriolis-based sensing. Mass flow controllers combine a mass flow meter, a control valve, and electronics to adjust the valve and keep flow on setpoint. Volume flow meters measure velocity or displace known volumes and infer flow from geometry.

In pharmaceutical work, this distinction turns into practical rules of thumb derived from selection guides. When you are dosing a liquid API, solvent, or methanol into a reactor, mass flow is often preferable because you care about actual mass ratio in the reaction. When you are distributing purified water or water for injection (WFI), volume flow tends to be more convenient because density is stable and many design standards are framed around volume.

For gases such as nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide, and compressed air, mass flow is usually the engineering preference since mass use relates directly to gas consumption, cost, and combustion or inerting performance. That is why technologies like thermal mass flow meters and Coriolis gas meters show up repeatedly in pharmaceutical gas applications.

Modern pharma plants use a portfolio of flow meter technologies. Each is grounded in a distinct physical principle, and each comes with characteristic strengths and limitations that matter in a GMP environment.

Turbine flow meters measure flow by placing a bladed rotor in the fluid stream. As the liquid passes, it spins the rotor, and electronics convert rotational speed into flow rate. Technical materials from BCST Group and GAIMC describe turbine meters as highly accurate and linear, with typical accuracies around plus or minus half a percent of reading and, under controlled conditions, even tighter.

In pharmaceutical service, sanitary turbine meters have been developed with 316L stainless steel, polished surfaces, self-draining internals, and tri-clamp (Tri-Clover) sanitary connectors. These features support clean-in-place and sterilize-in-place regimes and meet regulatory expectations for sanitary design. In one example, a sanitary turbine meter range of roughly 0.1 to 100 liters per minute equates to about 0.03 to 26 gallons per minute, with particular strength in small-flow detection at the low end. That makes them attractive for vial, syringe, and IV bag filling where precise small-volume control is crucial.

However, turbine meters are picky about what they see. Guidance from several sources is consistent: they are best suited to noncorrosive, relatively clean, low-viscosity fluids. Significant particulates, bubbles, or high viscosity can damage bearings or distort the calibration. For that reason, turbine meters are excellent in well-filtered, low-viscosity filling and batching operations but are less suitable for viscous suspensions, slurries, or liquids that may carry entrained gas.

Coriolis flow meters measure mass flow directly. They drive one or more tubes into vibration; as fluid flows through, inertia causes a phase shift or twist in the tubes. Electronics measure that twist and calculate mass flow. As explained in technical references and application notes, the big advantage is that the measurement is largely independent of pressure, temperature, and fluid properties. Many Coriolis meters simultaneously provide density and temperature, which adds value for process monitoring and control.

Pharmaceutical and chemical applications cited in manufacturer guides show Coriolis meters used for corrosive chemicals, high-purity systems, and critical dosing. All-metal, crevice-free wetted paths and bent or straight tube designs support hygienic operation without pockets where residues can accumulate. An example from a process industry guide reports that replacing older technology with Coriolis meters for reactant dosing improved yield by about half a percent and saved more than a million dollars per year in raw materials, underscoring what mass-accurate dosing can deliver when feedstocks are expensive.

In pharma, that same capability translates to precise API dosing, solvent addition, and methanol dosing for wastewater treatment, where RL Technologies points out that Coriolis meters can simultaneously supply density, temperature, volume, concentration, and solids percentage. The trade-offs are familiar to instrumentation engineers: higher purchase price, higher pressure drop compared with some volumetric technologies, and a need to consider vibration in the installation. For critical streams, though, the life-cycle economics are often favorable.

Thermal mass flow meters are designed primarily for gases. They use a heated sensor and a reference sensor immersed in the gas stream. As gas flows by, it carries heat away from the heated sensor; the power required to maintain a fixed temperature difference is proportional to mass flow. Articles by TechStar, BCST Group, and others highlight how this principle is similar to wind chill: more mass flow means more cooling.

Thermal mass meters shine in pharmaceutical gas applications. TechStarŌĆÖs analysis identifies tablet and pill coating, nitrogen blanketing, nitrogen purging, and gas flow monitoring in airborne infection isolation rooms as representative use cases. Coating processes are extremely sensitive to airflow; variations affect temperature, humidity, and coating delivery rate. High-precision, fast-response thermal meters allow the control system to hold airflow within a tight band, which reduces coating defects and appearance flaws that would otherwise compromise consumer confidence.

In nitrogen blanketing and purging, thermal mass meters provide both safety and efficiency. They help ensure sufficient nitrogen delivery to exclude oxygen and reduce explosion risk, while tracking actual usage to control costs and detect leaks. In compressed air systems and isolation rooms, they contribute to maintaining correct pressure differentials and can flag filtration problems.

Thermal meters offer several practical advantages: negligible pressure drop because the probes occupy a small cross-section, high turndown, and good low-flow sensitivity. However, their accuracy depends on knowing gas composition and keeping the gas relatively clean. Manufacturers note that thermal meters perform best with stable, clean gases such as nitrogen and compressed air rather than dirty or composition-changing mixtures.

Ultrasonic flow meters use sound waves to measure flow. Transit-time designs send pulses both with and against the flow; the difference in travel time is related to flow velocity. Clamp-on ultrasonic meters mount transducers on the outside of the pipe, avoiding any wetted components. Inline ultrasonic meters place the transducers in or around the flow path.

Technical documentation from industrial flow instrument providers explains several benefits of ultrasonic meters. Clamp-on designs do not require pipe cutting, do not introduce any pressure drop, and pose virtually no contamination risk. This makes them attractive in high-purity deionized water services, WFI distribution, RO water, and lines where mechanical modification is not possible or permissible. For example, one clamp-on meter series is described with typical accuracy around plus or minus one percent of reading and reliable low-flow measurement, with outputs suited for SCADA or PLC integration.

Pharmaceutical case material also shows clamp-on ultrasonic and external insertion meters used when water authorities or plant operators cannot interrupt or puncture large-diameter pipelines, including pipes up to around 6,000 millimeters. In high-pressure networks where no penetration is allowed, clamp-on becomes the default choice.

Inline ultrasonic meters, while more invasive, offer higher stability and are less sensitive to coupling conditions. Across both styles, there are important preconditions. Pipes must run full, air bubbles should be minimized, and wall thickness and material must be accounted for. Where those conditions are met, ultrasonic meters deliver non-intrusive measurement with modest installation effort.

Electromagnetic flow meters, or magmeters, apply FaradayŌĆÖs law. A conductive fluid moving through a magnetic field generates a voltage proportional to velocity. Industrial guides describe magmeters as having no moving parts, no intrinsic pressure loss, and being largely unaffected by changes in density or viscosity. They have become the dominant choice in water and wastewater applications.

In pharmaceutical and water treatment contexts, electromagnetic meters are used on untreated water, treated effluent, chemical dosing, and sludge streams. RL Technologies documents how PTFE liners are used on untreated water inlets where abrasion and solids are present, while different liners are used on treated or potable water outlets for corrosion and abrasion resistance. They also highlight how battery-powered magmeters with specialized coils can measure very low velocities down to about 0.1 meters per second, roughly 0.33 feet per second, enabling detection of leakage flows that conventional meters miss.

The key limitation is that magmeters need conductivity. According to selection guidance, electromagnetic meters are unsuitable for very low conductivity fluids such as high-purity RO water, where conductivity can fall below about five micro-mho per centimeter. In such cases, ultrasonic or vortex meters are recommended.

Variable area meters, often called rotameters, are simpler instruments consisting of a float moving in a tapered tube. They provide a visual indication of flow without external power. Industrial overviews place them as low-cost solutions for lab utilities, noncritical air and water lines, and some chemical feeds. In pharma, they might appear on noncritical utilities rather than validated product streams because their accuracy is limited compared with mass or high-end velocity meters.

Knowing the principles is one thing; seeing how they map onto actual pharmaceutical processes is where specification decisions are really made. Industry case material across multiple vendors sheds light on the highest-impact applications.

Pharmaceutical manufacturing begins with raw material and API receipt. Flow metering on incoming liquid streams ensures the correct quantities are transferred into storage or directly into process. BCST Group notes that raw material flow metering supports recipe integrity by making sure precise levels of materials are present for every step of chemical synthesis.

Within reactors and blending vessels, flow meters control the addition of APIs, excipients, solvents, and catalysts. BurakŌĆÖs discussion of flow meters in batch production and blending emphasizes that accurate flow control is essential to produce homogeneous mixtures and keep each batch within specification. Here, sanitary turbine meters and Coriolis mass flow meters are common choices. Turbine meters excel where the fluid is clean and low viscosity, such as some solvents and solutions. Coriolis is favored when mass accuracy and fluid independence are paramount, especially for expensive APIs or reactive components.

For fermentation media feeding bioreactors, IntekŌĆÖs Rheotherm flow meters illustrate another design goal: low pressure drop and easy sterilization. A straight-through stainless steel sensor design supports clean-in-place and steam-in-place, and in some cases sensors are designed to withstand autoclave sterilization. Typical flow ranges for fermentation feeds cited in that context go from a few ounces per hour up to around one and a half gallons per hour, showing that specialized low-flow measurement is often required.

Pharmaceutical facilities consume large volumes of gases. TechStarŌĆÖs analysis points out that excessive gas consumption wastes money and can impact quality and safety. Nitrogen is used for blanketing and purging, oxygen and air for combustion and aeration, and various gases for inerting and packaging.

Thermal mass flow meters are typically deployed on nitrogen blanketing and purging systems to control delivery and detect abnormal usage that may indicate leaks. For tablet and pill coating, both TechStar and BCST Group describe the importance of stable airflow to maintain coating thickness, avoid film cracking, and prevent visual defects. High-sensitivity thermal meters with fast response help maintain that stability.

Compressed air is another major focus. RL Technologies documents thermal mass meters used to monitor compressed air in aeration basins and biogas streams in wastewater treatment. Similar principles apply in pharma plants: measuring air to critical consumers supports energy efficiency and ensures adequate supply to devices like air-operated valves and instruments.

Steam measurement, often for sterilization and HVAC, is usually handled by vortex or differential pressure meters. Sterling Pharma Solutions describes using vortex flow meters for steam along with pressure transmitters rated up to about 356┬░F to monitor utility supplies. Integrating these with a building management system (BMS) allows the plant to track steam usage, detect filter blockages via differential pressure, and coordinate maintenance.

Purified water and WFI are among the most tightly controlled utilities in pharma. Flow meters track distribution to points of use and help validate that sanitization and circulation regimes are maintained. However, the very high purity of this water can make electromagnetic flow meters unsuitable due to low conductivity. RL Technologies notes that when water conductivity drops below about five micro-mho per centimeter, ultrasonic inline or vortex meters are preferred.

Clamp-on ultrasonic meters such as those described by industrial suppliers are especially attractive in retrofit projects because they can be installed without cutting or penetrating stainless steel WFI loops. Non-intrusive measurement minimizes the validation burden and contamination risk. Inline sanitary turbine meters can also be used where conductivity and viscosity make them feasible, leveraging their high accuracy for dosing purified water in formulation and filling.

Clean-in-place and sterilize-in-place cycles are central to hygiene and contamination control. Manufacturers of flow meters and selection guides highlight that hygienic meters must tolerate hot chemicals and acids during CIP, often up to about 200┬░F, and saturated steam during SIP up to roughly 284┬░F.

Sanitary turbine meters and ultrasonic meters are both designed to withstand CIP/SIP environments when constructed from appropriate materials. GAIMC describes 316L stainless steel turbines with polished, crevice-free internals and clamp connections that can handle cleaning solutions and sterilization temperatures around 266┬░F without degrading performance. Ultrasonic meters with non-intrusive sensors naturally avoid product contact and do not disturb cleaning validation.

Accurate flow measurement during CIP is used to verify that sufficient cleaning solution volume and velocity reach every part of the system. This supports cleaning validation records and helps optimize chemical usage. In wastewater and water treatment contexts, electromagnetic flow meters, sometimes with PTFE liners, are also used around filters and treatment stages to monitor raw and treated water flows, illustrating how similar technology supports both product and environmental compliance sides of a pharma operation.

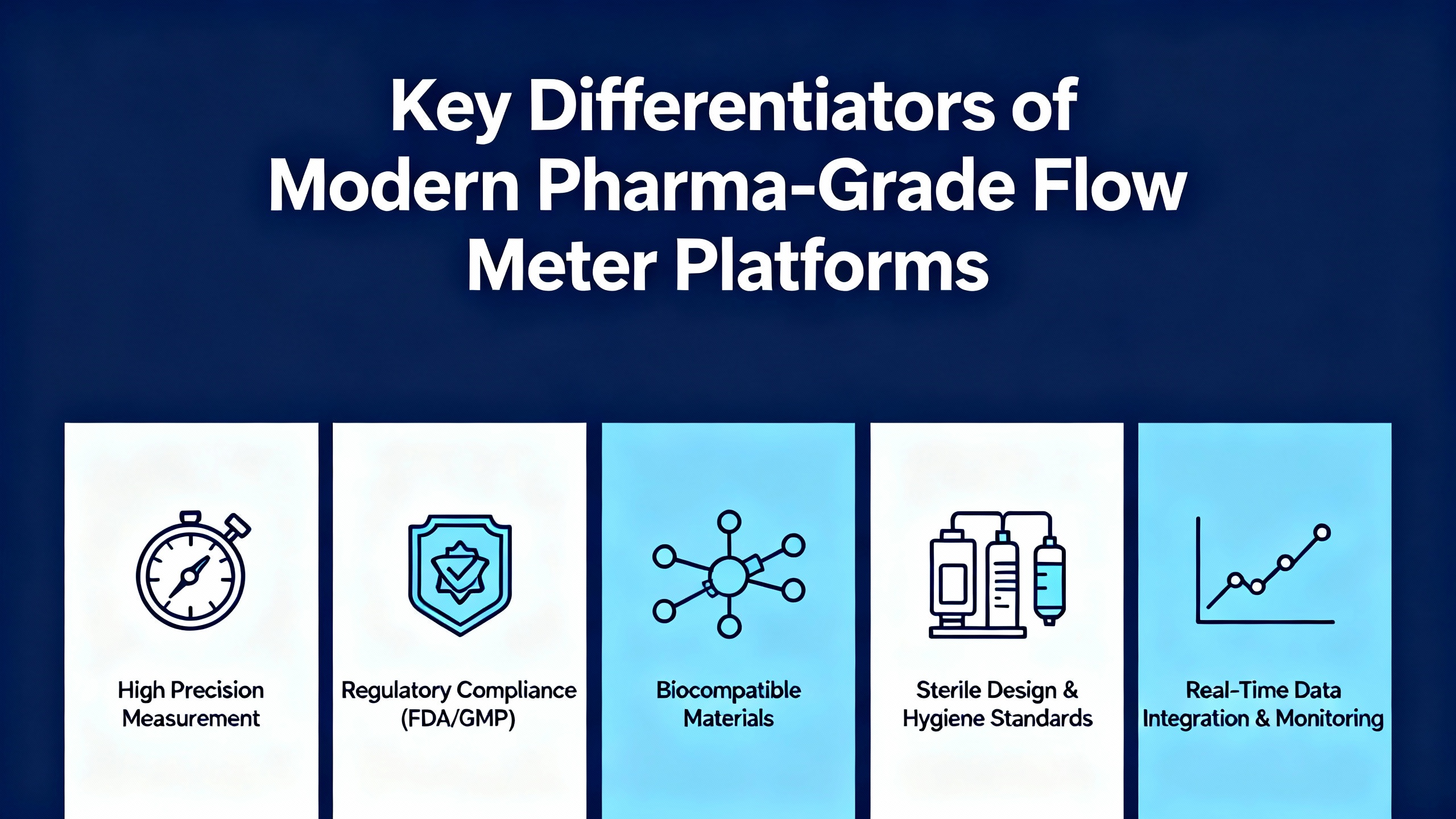

If you strip away branding and look at the core capabilities described across technical articles from BCST Group, TechStar, GAIMC, VPInstruments, RLT, and others, you see a consistent picture of what a modern, pharma-capable flow meter platform should offer. These are exactly the kinds of capabilities you should expect when you evaluate solutions from major suppliers, including a Yokogawa system environment.

First, high accuracy and repeatability matched to the application. For most critical pharmaceutical duties, the general ranges seen in flow instrumentation guides apply. Coriolis meters offer accuracies around a tenth of a percent of reading for liquids, calibrated positive displacement meters around two-tenths of a percent, ultrasonic meters around a third of a percent in master-metered setups, and magmeters around half a percent when properly installed. Repeatability is just as important as absolute accuracy because it underpins process stability and statistical control.

Second, hygienic and cleanable mechanical design. Sanitary turbine meters and Coriolis meters for high-purity applications rely on polished stainless steel, self-draining geometries, and clamp connections. Straight-through or straight-tube designs simplify cleaning and minimize dead legs. The ability to withstand repeated CIP and SIP cycles at the temperatures and chemical concentrations used on site, without drift or damage, is an essential qualification.

Third, diagnostic and maintenance-friendly electronics. VPInstruments describes flow meters with exchangeable sensor cartridges to reduce downtime for recalibration. RL Technologies highlights magmeters with built-in diagnostics that expose sensor coil strength so users can see when a device is drifting out of its active life. These are all examples of the same trend: meters that tell you not only the process variable but also their own health, making calibration planning and troubleshooting more efficient.

Fourth, integration with control, power, and energy management systems. SterlingŌĆÖs BMS project shows how linking flow and pressure measurements for water, steam, air, and nitrogen into a building management system can reveal patterns, improve utilization, and support carbon neutrality targets. VPInstruments goes further by combining flow and electric power measurement to quantify the true energy cost per unit of compressed air or technical gas. Meters with analog outputs and digital communications such as 4ŌĆō20 mA, RS485, and modern fieldbuses slot cleanly into distributed control systems and historians.

Finally, suitable turndown and dynamic range. Selection texts emphasize that a flow meter should have a measurement range wide enough to cover both minimum and maximum flows while still keeping the operating region inside the specified accuracy band. Technologies like turbine, ultrasonic, and thermal mass flow meters can offer turndown ratios from ten-to-one up to several tens-to-one, which is important in batch and multipurpose lines where flows can vary widely.

A concise way to think about these trade-offs for major principles is summarized below.

| Principle | Typical pharma use | Main strengths | Main considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turbine | Clean liquids, filling, batching | High accuracy, good small-flow detection, sanitary designs | Needs clean, low-viscosity fluids; sensitive to bubbles |

| Coriolis | Critical dosing, corrosives, methanol, multiphase | Direct mass, density, temp; fluid-independent | Higher cost, higher pressure drop, vibration sensitivity |

| Thermal mass | Nitrogen, compressed air, tablet coating gases, biogas | Direct gas mass, minimal pressure drop, high turndown | Requires known gas mix, clean gas for best performance |

| Ultrasonic | Purified water, WFI, RO, large pipes, retrofits | Non-intrusive options, no pressure drop, broad pipe sizes | Needs full pipes, low bubbles; installation-sensitive |

| Electromagnetic | Raw water, treated water, slurries, chemical dosing | No moving parts, no pressure loss, tolerant of solids | Needs sufficient conductivity; not for ultra-pure water |

| Variable area | Noncritical utilities, labs, local indication | Simple, low cost, no power, visual indication | Limited accuracy, not ideal for opaque or dirty fluids |

All of these capabilities are available in the market today; the engineering task is to align them with your specific pharmaceutical process constraints and your overall automation and power strategy.

Flow meter selection guidance from specialist companies converges on a set of practical factors you should formalize in your user requirements. Rather than treating selection as a one-line ŌĆ£type and size,ŌĆØ treat it as an engineered decision.

Start with fluid properties. Determine whether the medium is gas, liquid, steam, or a multiphase mixture. Note conductivity, viscosity, corrosiveness, solids content, and whether composition changes over time. For instance, magmeters require a minimum conductivity; they are excellent for water and many aqueous chemicals but unsuitable for ultra-pure RO water. High-viscosity or sticky fluids call for technologies like positive displacement or certain Coriolis designs rather than turbines.

Next, define process conditions. Establish normal and extreme flow rates using realistic operating scenarios, not just theoretical pipe capacity. Capture inlet and outlet pressures, allowable pressure drop, temperature ranges, and whether the line may see vacuum, high pressure, or high temperature events. Selection notes point out that very low velocities, below about 0.33 feet per second, can challenge many meters, so specialist solutions are needed where leakage detection at very low flows is required.

Then, clarify accuracy and repeatability requirements. For custody transfer or high-value APIs, you may need accuracy better than a few tenths of a percent. For routine monitoring of utility flows, a few percent may be perfectly acceptable. Make sure you distinguish between absolute accuracy and repeatability; many combustion and utility applications prioritize repeatability so that control loops behave consistently, even if the absolute reading is slightly offset.

Consider installation environment and constraints. Think about straight pipe runs available upstream and downstream, pipe size, whether you can cut or weld the line, and accessibility for maintenance. Some technologies need long, straight runs to achieve their specified performance, while others, like some Coriolis and certain compact meters, are more tolerant. In older facilities where pipe modifications are difficult, clamp-on ultrasonic or insertion-style meters provide retrofit options without long outages.

Hygiene and cleanability are nonnegotiable in product-contact applications. Selection guides emphasize choosing meters with materials and seals compatible with CIP chemicals and SIP steam temperatures, and with geometries that avoid crevices and dead legs. If the meter must be removable for autoclaving, that should be specified at the outset.

Finally, account for life-cycle cost, not just purchase price. Differential pressure meters, for example, can be inexpensive upfront but introduce permanent pressure loss, which raises pumping energy over time. Thermal mass and ultrasonic meters may have higher initial cost but low pressure drop and minimal maintenance. Calibration intervals also matter: mechanical meters may require annual calibration, while static devices like ultrasonic or magmeters can often run two to four years between calibrations, subject to regulatory and internal quality requirements. For critical GMP applications, shorter, traceable intervals will apply regardless of technology.

From the standpoint of a power and reliability engineer, this life-cycle viewpoint should feel familiar. A meter that looks inexpensive at the catalog level can turn into a long-term liability if it forces you to oversize pumps or compressors, adds unplanned downtime for cleaning or bearing replacements, or drives complex recalibration logistics.

Experience from UPS and power protection equipment gives useful parallels for maintaining reliable flow measurement. UPS maintenance guides stress that even in seemingly clean environments, dirt, dust, sawdust, and metal filings accumulate inside equipment. Contaminants on relay and contactor contacts can cause failures, and conductive particles can create short circuits and malfunctions on circuit boards. Cleaning is recommended at least annually, using careful vacuuming with non-conductive tools rather than blowers or compressed air, which simply drive contaminants deeper. All work is done with the equipment de-energized, and technicians use appropriate personal protective equipment.

Flow meter transmitters, local control panels, and marshalling cabinets share many of the same vulnerabilities. While the process connection may be stainless steel and designed for harsh chemicals, the electronics that interpret signals and communicate with the DCS still require a clean, dry, and well-ventilated environment. Borrowing from UPS practice, a disciplined schedule of cabinet inspection, gentle vacuum cleaning, torque checks on terminations, and review of diagnostics helps prevent intermittent faults and unexplained signal dropouts.

On the process side, easy cleanability of sensors is vital. IntekŌĆÖs Rheotherm insertion probes used on pill coating dryers are designed to have no mechanical parts or orifices that can be fouled by sticky coating material, and when equipped with sanitary connections, sensors can be extracted quickly for wiping or solvent cleaning without damage. That sort of design consideration pays off in reduced downtime, especially on lines where any stoppage is expensive.

Diagnostic features built into modern meters further support reliability. RL Technologies describes how electromagnetic flow meters with in-built ŌĆ£coil strengthŌĆØ diagnostics allow users to distinguish between an aging sensor and mere calibration drift. Portable clamp-on ultrasonic meters can then be used as temporary standards to validate the installed meter, aligning with ISO guidelines on field validation. On the utility side, SterlingŌĆÖs BMS project illustrates how linking flow, pressure, and differential pressure into a central system enables predictive maintenance; for example, automatically identifying when a water filter is approaching blockage so maintenance can be scheduled before production is impacted.

Calibration strategy is another reliability lever. Guidance from comprehensive flow meter handbooks suggests annual calibration for mechanical meters such as turbines and positive displacement devices, and two- to four-year intervals for static meters like ultrasonic and magmeters, with critical applications requiring shorter intervals for traceable compliance. In a pharmaceutical context, calibration intervals are often dictated by the quality system, but understanding inherent stability helps you defend your chosen interval to auditors.

In short, if you treat flow meters with the same preventive care and disciplined attention you devote to UPS systems and protective relays, they will repay you with quiet, predictable service instead of surprise deviations.

For critical liquid dosing where mass ratios matter, Coriolis mass flow meters are generally the most robust choice because they measure mass directly and are relatively insensitive to temperature and pressure changes. For clean, low-viscosity liquids where volume flow is sufficient and where small-flow resolution is important, sanitary turbine meters provide high accuracy and fast response. Selection guides also point to positive displacement meters in some high-viscosity or custody transfer situations, but these see less use in hygienic pharmaceutical lines compared with sanitary Coriolis and turbine designs.

Technical guidance from flow instrumentation references recommends annual calibration for mechanical meters such as turbine and positive displacement devices and calibration every two to four years for static meters such as electromagnetic and ultrasonic instruments, assuming stable service conditions. In regulated pharmaceutical environments, actual intervals are usually shorter and driven by criticality, historical stability, and quality procedures. Critical GMP-critical meters may be calibrated yearly or even more frequently, while noncritical utilities might follow the longer intervals suggested by manufacturers, supported by diagnostics and occasional field validation with portable standards.

Clamp-on ultrasonic meters are particularly useful when you cannot cut or weld existing piping, when you are working on very large-diameter or high-pressure lines where insertion is not practical, or when the process fluid has very low conductivity that rules out electromagnetic meters. They are frequently used on high-purity water and RO lines, in water distribution networks, and in retrofit projects where downtime must be minimized. They require full, bubble-free pipes and careful attention to transducer mounting and pipe data but, when those conditions are met, provide reliable flow data without introducing any new wetted materials into the system.

As with critical power systems, the most robust pharmaceutical facilities are built on instrumentation that is specified thoughtfully, installed correctly, and maintained with discipline. When you treat flow metering as part of your reliability architecture rather than just a catalog line item, you get cleaner batches, fewer deviations, and a plant that behaves predictably under pressure.

Leave Your Comment