-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Gas turbine control panels are quietly deciding whether your plant starts on demand, rides through grid disturbances, and protects expensive rotating equipment when something goes wrong. In utility peakers and industrial cogeneration plants, these panels sit alongside UPS-backed switchgear controls, generator protection relays, and emergency power systems. When they are modern, predictable, and well-integrated, the whole power system behaves more like a coordinated power protection ecosystem than a collection of individual devices. When they are not, every start becomes a gamble.

Aging gas turbine fleets and rising expectations for reliability and flexibility are now forcing owners to ask a hard question: do we refurbish, recommission, or completely replace the turbine control panel? The answer is no longer just ŌĆ£do what the OEM says.ŌĆØ A mature ecosystem of open-architecture solutions, specialized retrofit providers, and advanced digital control technologies has emerged, giving operators real alternatives.

This article walks through those alternatives, using real cases from utilities and industrial plants, and offers practical guidance on how to choose the right path for your unit without compromising power system reliability.

Many gas turbines installed from the early 1990s onward are still running on their original digital controls. In parallel, newer peaking obligations and variable renewable output have increased the need for fast, reliable starts and flexible operation. According to Mechanical Dynamics & Analysis, recommissioning work on two GE Frame 7EA units with Mark V controls found that up to about thirty percent of field devices in calibration checks failed, despite the systems still being technically ŌĆ£in service.ŌĆØ That kind of hidden degradation is typical when panels and devices run far beyond their intended support horizon.

A major concern is obsolescence of proprietary ŌĆ£black boxŌĆØ controls supplied by the turbine OEM. Power Engineering has described how closed-architecture systems prevent owner-operators from viewing live logic, modifying control strategies, or even repairing human-machine interfaces with readily available hardware. When a client computer failed at one independent power producer, the operator was forced to work directly at an HMI next to high-voltage breakers in an arc-flash zone for weeks while the OEM-specific hardware was shipped out and repaired. That is a reliability and safety problem, not just an inconvenience.

At the same time, modern power markets are less forgiving. The Mark V and earlier generations were installed into power systems that expected occasional peaking or steady baseload operation. Today, those same machines are asked to cycle frequently, follow load, black-start plants, or island a city during grid contingencies. TTS Energy Services reports that Tucson Electric Power requires its Valencia plant to be able to operate in island mode to serve Nogales, Arizona if the transmission tie is lost. In that context, the control panel is not just a turbine brain; it is a critical part of regional power security.

Legacy panels also limit performance. A PubMed Central study on model predictive control integrated into a large gas turbine showed that advanced optimization of pilot gas valves, main natural gas valves, and compressor pressure ratio control improved combined-cycle thermal efficiency by about 1.1 percent while enhancing load-frequency performance. Older controls with fixed logic and basic proportional-integral-derivative loops simply cannot exploit that type of optimization.

Finally, older controls can delay or prevent compliance with emissions and cybersecurity requirements. Modern systems such as the advanced control platforms discussed on the AutoCS Blog and by Petrotech incorporate predictive analytics, better combustion control, and open-architecture networking that is easier to harden under standards like NERC Critical Infrastructure Protection. Closed, unsupported panels are much harder to secure, patch, and audit.

For owners, all of this converges into one conclusion: legacy gas turbine control panels are increasingly the weak link in an otherwise robust power supply system.

A gas turbine control panel is more than a governor. It is a coordinated control, protection, and information system that touches every major aspect of turbine operation and its interface to the wider power system.

On the process side, the panel regulates fuel flow, air flow, and firing temperature. The CallGTC article on gas turbine speed control describes how governors, fuel control systems, and combustion control strategies all interact to keep speed and load within safe limits. Mechanical, hydraulic, or electronic governors adjust fuel to match load. Fuel control strategies can be single-point or multi-point, with variable geometry control at guide vanes to fine-tune airflow. Combustion control methods such as lean combustion, staged combustion, or dry low emissions (DLE) combustion reduce emissions while preserving stability.

On the electrical and grid side, the panel interfaces with generator excitation and protection. In a case study from Petrotech, a GE Frame 5 generator with an outdated excitation system was upgraded to a microprocessor-based digital excitation control system. The new system regulates voltage, reactive power, and power factor while protecting the generator against abnormal operating conditions. In the same project, turbine fuel regulation was modernized to ensure precise speed and load control in either isochronous or droop modes, with smooth transitions under load. That kind of coordination between fuel control, speed sensing, and excitation is central for black-start and island operation.

The panel also provides the human-machine interface and connectivity to plant networks. TTS Energy Services describes how at the Valencia plant, legacy turbine controls and older GE Fanuc platforms were replaced with Rockwell Automation ControlLogix controllers, distributed I/O, FactoryTalk View SE for HMI, and FactoryTalk Historian SE. Modern HMIs give operators graphical visibility into speed, exhaust temperature, voltage, real power, and alarms. Historian databases enable trend analysis and performance audits.

Finally, the control panel forms part of the protection and power quality layer. Overspeed protection, flame monitoring, vibration monitoring, and emergency trip logic are implemented here. CallGTC emphasizes that failures in speed governing, faulty sensors, or delayed load shedding can all contribute to dangerous overspeed events. Upgrades often integrate dedicated overspeed protection devices, such as the independent overspeed system TTS installed on the LM2500 at Valencia, and vibration monitoring systems like the Bentley Nevada platform at the same site.

Viewed this way, upgrading the control panel is not just a technology refresh. It is a power system reliability project that needs to be treated with the same rigor as UPS design, generator protection, and switchgear coordination.

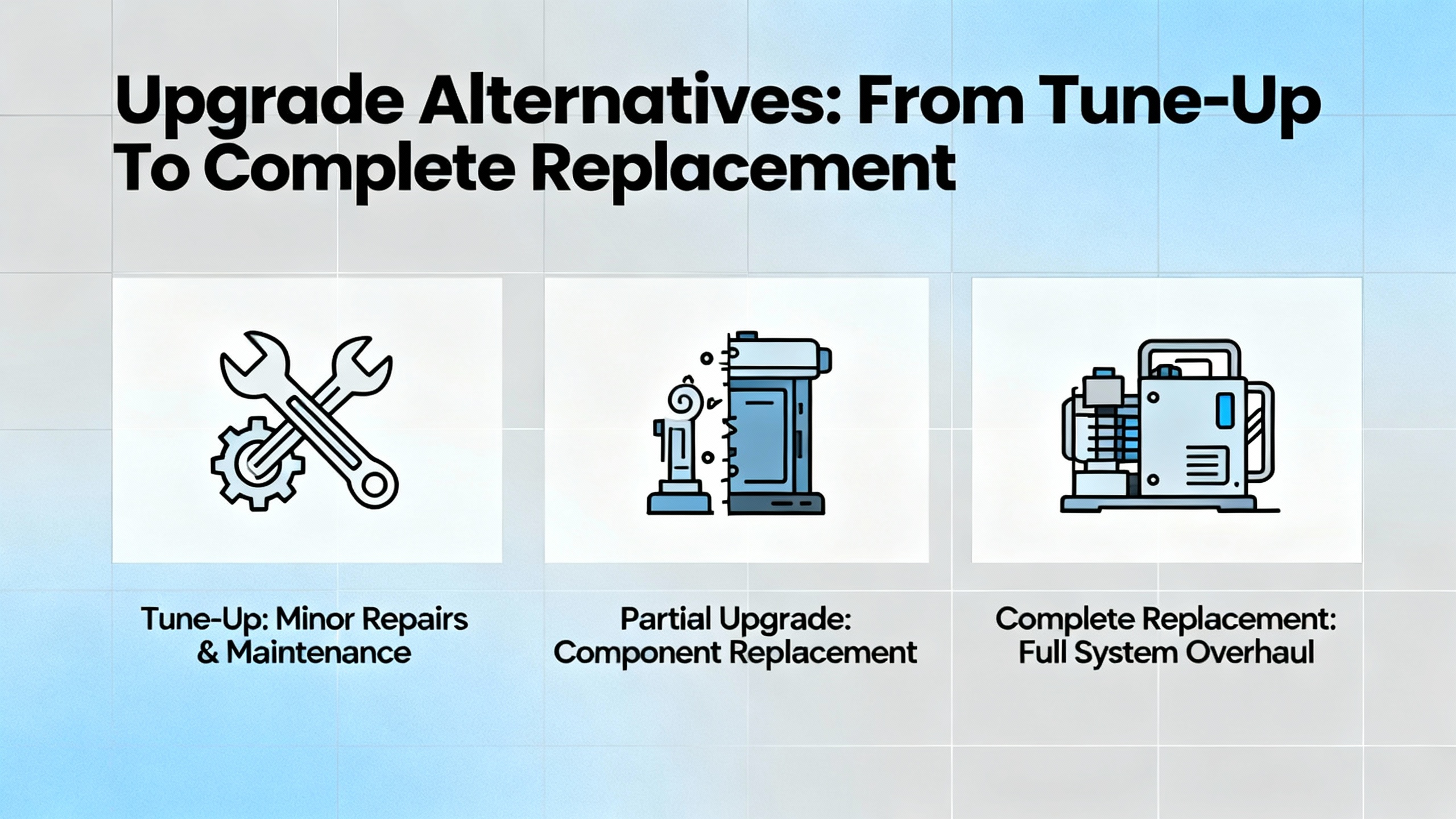

There is no single correct path for every plant. The practical options fall into four broad strategies, which can be combined or sequenced over time.

In many plants, the fastest reliability gains come from recommissioning what is already installed. Mechanical Dynamics & Analysis describes recommissioning work on two GE Frame 7EA gas turbines with Mark V controls used for peaking service. Comprehensive calibration checks on those units showed device failure ratios up to about thirty percent. Primary tasks were I/O loop checking, function testing, and operating checks on all field devices and connections. Non-working field devices were recalibrated or replaced, junction box issues threatening the fire protection system were corrected, and incorrect wiring was discovered and addressed.

MD&A reports that this type of recommissioning can be done at roughly ten percent of the cost of a full controls replacement and with significantly less outage time. They also commonly enhance legacy systems with a modern HMI, which gives operators better visibility and reduces nuisance and false alarms. For plants with limited capital but urgent reliability issues, recommissioning is often the most cost-effective starting point.

The trade-offs are clear. Recommissioning does not eliminate obsolescence; it simply restores an older system to its best achievable condition. Network security, integration with modern analytics, and advanced optimization remain constrained by the old platform. However, as a bridge strategy, it can dramatically reduce start failures and nuisance trips while giving the owner time to plan a larger transformation.

A second strategy is partial modernization, where the owner leaves the core turbine logic platform in place but upgrades key subsystems such as excitation, fuel regulation, speed sensing, and the HMI. The Petrotech case study on a GE Frame 5 black-start unit in New York illustrates this approach.

In that project, an outdated excitation system was replaced with a microprocessor-based digital excitation control system. This new system regulates generator voltage, reactive power, or power factor by controlling direct current excitation, and includes functional limits and protections. Simultaneously, Petrotech implemented a Turbine Fuel Regulation system built from mature function blocks with millions of operating hours, along with upgraded speed sensors to support stable isochronous and droop modes. The HMI was also modernized to a touchscreen panel with real-time trending of speed, exhaust gas temperature, generator voltage, and real power.

The documented benefits included higher turbine efficiency, improved reliability, and greater operational flexibility. The system could now respond quickly to load rejections and increases while maintaining frequency within acceptable limits, reducing overspeed trip risk and enabling rapid reestablishment of loaded operation.

TTS Energy Services applied a similar philosophy at the Valencia LM2500 unit. They installed a Basler Electric DEC excitation system with power system stabilizer, a Schweitzer generator protection relay, AllenŌĆæBradley ControlLogix I/O, isolated analog and thermocouple inputs, RTD inputs, and a new HMI. Integration with existing Woodward fuel valves was achieved using the latest drivers applicable to each valve. After full loop checks and field device interrogation, they commissioned the generator protection and excitation, conducted power system stabilizer tests, and successfully performed a black-start test for the greater Nogales area.

Partial modernization offers a practical balance. It targets high-impact elements that influence reliability, power quality, and operator interaction, without incurring the full cost and risk of rewriting all core logic. However, it still inherits any structural limitations of the underlying control platform and usually does not fully solve obsolescence or cybersecurity concerns.

A more transformative option is to replace the turbine control panel with an open-architecture system built on a modern distributed control system or programmable automation controller platform. Turbine Logic, Petrotech, ABB in Power Engineering, and modernization case studies in Power magazine all highlight variants of this path.

Turbine Logic describes gas turbine control system upgrades focused on modernizing control software, HMIs, sensors, actuators, and communication protocols. Upgrades typically include enhanced algorithms for performance modeling and predictive analytics, improved visualization and control for operators, more accurate sensors and actuators, and updated communications to integrate with modern plant networks.

In one Power magazine case, an industrial plant moved from manual turbine startup, which required three operators coordinating by radio, to automatic start and synchronization. A controls retrofit allowed a single operator in the control room to start and synchronize the unit safely. Another utility with three gas turbines on a fifty-year-old control system improved starting reliability from roughly half of start attempts to more than ninety percent after a controls upgrade, with no subsequent failed starts attributed to the control system.

ABBŌĆÖs discussion of open systems in Power Engineering underlines the strategic differences. Black-box OEM systems lock algorithms and data away from the owner, forcing dependence on OEM engineers, customized hardware, and long turnaround times. Open systems, in contrast, provide full access to logic and process data, enable local repair using standard components, and can be integrated with control of the rest of the plant. That reduces hardware obsolescence risk, improves safety by avoiding improvised operation near high-voltage gear, and supports predictive maintenance because plant staff can directly analyze high-resolution process trends.

At TEPŌĆÖs Valencia plant, TTS implemented a standardized platform using Rockwell Automation ControlLogix controllers, distributed I/O, and FactoryTalk software for HMI and historian functions. This unified architecture across multiple turbine units simplifies spares management, operator training, and fleet-wide analytics. It also makes it easier to embed coordinated logic for island operation, load shedding, and black start.

The advantages of a full open-architecture replacement are strongest when viewed through a power system reliability lens. Unified, modern controls reduce start failures, enable more secure networking, provide better disturbance data for event analysis, and support integrated control of turbines, generators, auxiliary systems, and even UPS-backed protection devices. The main drawbacks are higher upfront cost, a larger commissioning scope, and the need for careful vendor selection and long-term support planning.

The final option is to replace the existing controls with the OEMŌĆÖs current control platform and upgrade packages. On paper, this seems like the safest path: the turbine manufacturer provides hardware, software, and documentation tuned to their machine. In practice, it is more complicated.

TC&E notes that OEMs often recommend upgrades such as moving from Mark IV to Mark V or Mark VIe whenever an owner asks for seemingly small changes like adding a pressure switch or hydraulic system. TC&E argues that this is frequently driven by internal staffing limitations rather than absolute technical necessity, especially when the OEM no longer has personnel who can maintain older logic. At the same time, they emphasize that for some units, particularly where extreme reliability is required, an OEM upgrade may be justified.

Modern OEM packages do offer real performance benefits. GE Vernova, for example, highlights combined solutions like Advanced Gas Path hardware, dry low emissions combustion, and OpFlex software upgrades that increase output and efficiency for older units. Their Autonomous Tuning solution uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to adjust fuel splits, firing temperatures, and airflows in near real time. That reduces thermal stress and hot spots in the hot section, stabilizes combustion to avoid instabilities and lean blowout, and smooths structural loads by reducing harmful vibration.

The key issue with OEM platforms is that they are usually closed architectures. The Power Engineering article points out that such systems make the owner a captive customer for troubleshooting, spare parts, and logic changes, often at high cost and with limited flexibility. Lifecycle management frequently follows a ŌĆ£rip and replaceŌĆØ model rather than an incremental migration path, and integrating third-party optimization or plant-wide analytics can be more difficult.

For owners who value tight integration with OEM hardware and have contractual or financing reasons to stay with the OEM, this option remains viable. The challenge is to weigh those benefits against long-term cost, flexibility, and self-sufficiency.

Beyond simply turning the unit on and off, modern gas turbine control panels bring a set of capabilities that directly influence power system resilience and operating economics.

Control systems are central to turbine performance optimization. The Energy Sustainability Directory emphasizes control systems as a key factor in maintaining optimal operating conditions and reducing performance losses from off-design operation. Modern controls can keep the turbine closer to its design sweet spot across varying load, temperature, and pressure conditions.

The PubMed Central study on model predictive control is a good illustration. By feeding optimized set points to the pilot gas valve, main natural gas valve, and compressor pressure ratio controller, the MPC-based strategy improved load-frequency response and thermal efficiency in a combined-cycle plant by about 1.1 percent. That may sound modest, but in a large plant it translates to significant fuel savings and reduced emissions over time.

GE VernovaŌĆÖs Autonomous Tuning example also shows how software-based improvements can protect hardware while optimizing performance. By continuously adjusting combustion parameters, the system reduces thermal stress in turbine blades, prevents combustion instabilities, and maintains low emissions without excessive water or steam injection. That is essentially an automated, continuous tuning process that would be impossible to replicate manually.

Petrotech emphasizes advanced control systems and open-architecture models as a strategy for turbine efficiency. In their GE Frame 5 project, upgrading the fuel regulation and generator control systems, alongside a modern HMI and diagnostic algorithms, resulted in increased turbine efficiency, better reliability, and more flexible operation, including operation in both isochronous and droop modes.

When your control panel upgrade is designed with performance in mind, it becomes an efficiency upgrade as much as a reliability upgrade.

Starting reliability may be the single most important metric for peaking units and emergency generation assets. Power magazine reports a case where a utility with three gas turbines on a very old control system improved starting reliability from about half of attempted starts to more than ninety percent after a controls upgrade, with no subsequent failed starts attributable to the new controls. In another case, a plant that previously needed three operators to coordinate a manual turbine start by radio moved to automated start and synchronization with a single operator in the control room.

MD&AŌĆÖs experience with recommissioning Mark V systems also shows that a systematic approach to calibrations and loop checks can reveal a large fraction of degraded devices and wiring issues. When these are corrected, nuisance alarms decrease and genuine alarms become more meaningful, which improves operator confidence and response.

From a power system perspective, better starting reliability means fewer forced outages, more dependable capacity during grid contingencies, and more predictable utilization of UPS-backed auxiliary systems that support start sequences. It also improves the economics of peaking plants that may be contractually obligated to meet dispatch requests or face penalties.

Safety is tightly linked to control architecture. The arc-flash scenario described in Power Engineering, where an operator had to stand near high-voltage breakers because a proprietary HMI client failed and had to be shipped back to the OEM, is an example of how closed systems can create unsafe workarounds. Open systems built on standard hardware and networks, as advocated by ABB and others, allow local repair or replacement, minimizing the need for operators to work in hazardous areas.

Modern controls also help with emissions compliance and operational safety. AutoCS notes that advanced gas turbine control systems with predictive analytics can detect early signs of wear, monitor parameters like temperature, pressure, vibration, and airflow, and automatically adjust operations to prevent catastrophic failures. Compliance with environmental regulations is supported by precise emission control, reducing nitrogen oxides and carbon dioxide output while keeping combustion stable.

Cybersecurity is an increasingly critical dimension. Power magazineŌĆÖs modernization article stresses that industrial security must protect intellectual property and prevent intrusions that threaten productivity, safety, or the environment. It recommends starting with a security assessment and implementing defense in depth, aligned with standards such as NERC Critical Infrastructure Protection. Open, information-enabled platforms like Rockwell AutomationŌĆÖs PlantPAx, which was used to replace an obsolete distributed control system in a California cogeneration plant, make it easier to implement modern security practices, including secure remote access and network segmentation.

Gas turbine controls do not operate in isolation. They sit on power and communication infrastructures that include UPS systems, dc distribution, generator protection relays, switchgear controls, and sometimes industrial UPS-backed loads such as critical process or data center equipment.

The Valencia project shows how the turbine control panel must coordinate with generator protection, excitation, and system stabilizers to perform black-start and island-mode operation. A Basler excitation system with a power system stabilizer, Schweitzer generator protection, and an independent overspeed system had to be tuned together with the new control logic. Extended testing included power system stabilizer trials and a black-start test where the plant powered the greater Nogales area during a simulated blackout.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs standpoint, a control panel upgrade is an opportunity to rationalize how turbine controls, UPS-backed control power, and protective relays share information, alarms, and trip signals. It is also the moment to check that control power sources are robust, redundant where needed, and protected by high-quality industrial UPS systems whose autonomy is matched to start and shutdown sequences. While the research sources focus on turbine controls themselves, practical projects should treat the control panel as part of an integrated power protection chain that includes UPS, inverters where present, and downstream protective devices.

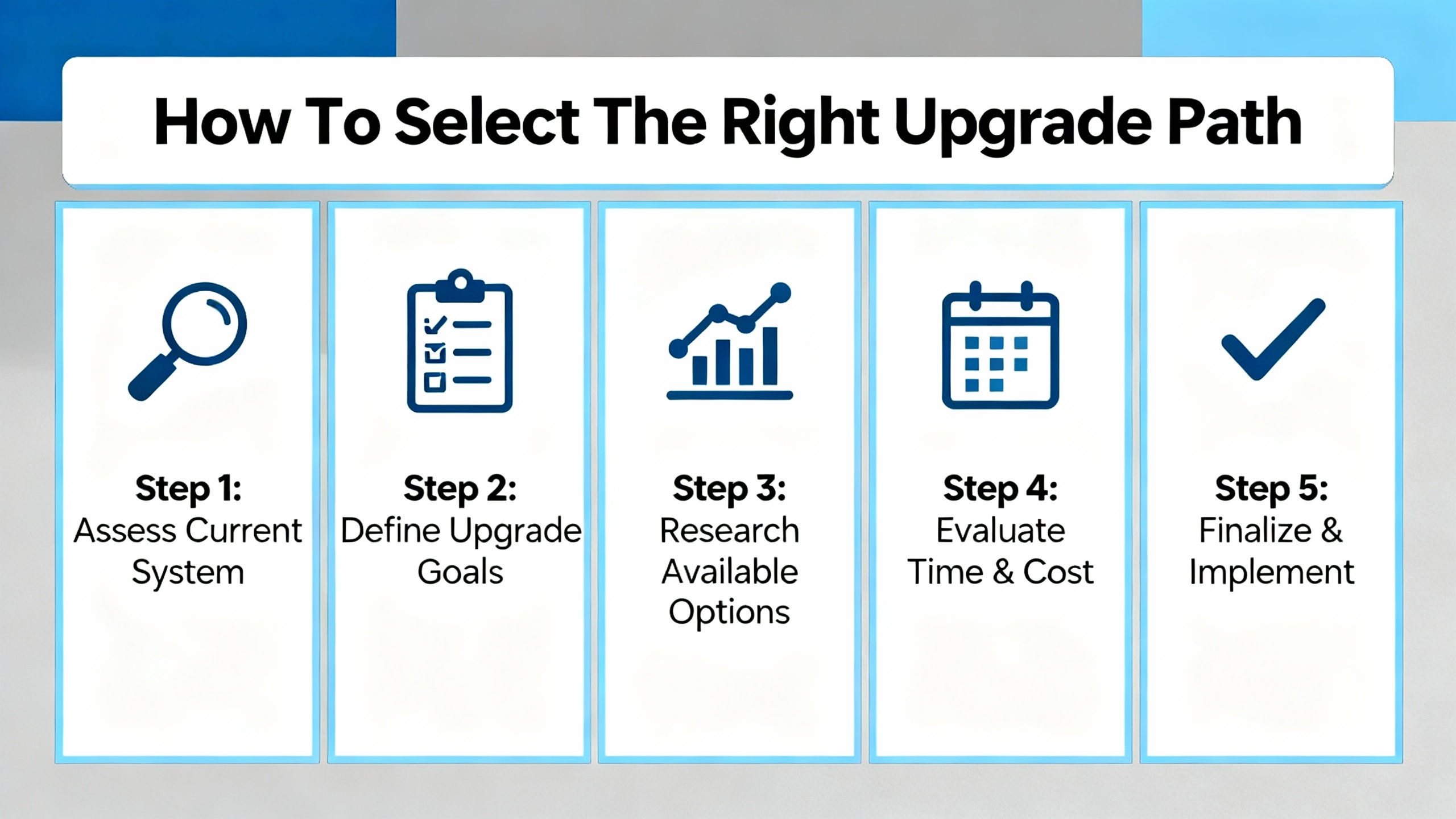

Deciding between recommissioning, partial modernization, open-system replacement, and OEM replacement requires aligning technical needs with operating philosophy and budget.

An experienced contributor on the Automation & Control Engineering Forum points out that the first question is how the turbine is or will be operated. If the unit must run continuously around the clock, a high degree of redundancy, such as triple modular redundant or dual redundant systems, may be justified to allow online replacement of failed components without shutting down the turbine. However, redundancy also increases the number of components and therefore the absolute number of failures over time, even if the failure rate per card does not change. More redundancy demands more spares and more disciplined maintenance.

If the turbine mainly provides peaking or backup service and can tolerate occasional outages during component failures, a simplex or lower redundancy solution may offer adequate reliability at much lower cost. In that case, as the forum contributor notes, owners should still focus on selecting a supplier that can implement the upgrade on time and within budget and provide strong after-installation support.

The second major dimension is technology philosophy. Power Engineering contrasts OEM closed systems with third-party open systems. Closed systems tie owners to a single vendor for parts and service, restrict access to diagnostics and logic, and often require sending components back to the OEM for repair. Open, plant-wide systems encourage integration of the gas turbine with boiler, balance-of-plant, and even industrial power supply systems, using common platforms and allowing the owner to become a self-maintainer to a greater extent.

Cost and outage duration are also critical. MD&AŌĆÖs recommissioning projects at around ten percent of a full upgrade cost are attractive for immediate risk reduction. Partial modernization, like PetrotechŌĆÖs DECS and fuel control upgrades or TTSŌĆÖs phased approach at Valencia, can be phased to avoid taking all units out of service at once. Full replacements or OEM migrations require carefully planned outages but offer longer-term benefits.

The table below summarizes the typical characteristics of each path.

| Upgrade path | Typical scope | Strengths | Limitations | Best suited for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommission existing controls | Calibration, I/O loop checks, wiring corrections, minor device replacement, HMI enhancement | Low cost and outage time, quick reliability gains, preserves existing wiring and logic | Does not solve obsolescence or security, limited performance improvements | Units needing fast reliability improvement with minimal capital |

| Partial modernization | New excitation, fuel regulation, speed sensors, generator protection, HMI and historian | Targets high-impact subsystems, improves efficiency and stability, enhances operator visibility | Still constrained by core control platform and networking | Plants wanting better performance and reliability without a complete platform change |

| Open-architecture replacement | New PLC or DCS-based control panel, modern I/O, integrated HMI, plant network integration | Owner access to logic and data, standard hardware, easier cybersecurity, supports plant-wide optimization and analytics | Requires careful design and vendor selection, higher upfront cost and commissioning effort | Plants seeking long-term flexibility, integrated control, and reduced dependence on OEM |

| OEM control system replacement | Migration to current OEM platform plus optional performance and combustion upgrade packages | Tight integration with OEM hardware, access to OEM upgrade packages and performance improvements | Closed architecture, potential vendor lock-in, sometimes high lifecycle cost and limited flexibility | Units where OEM relationship, warranty, or specific upgrade packages are strategic priorities |

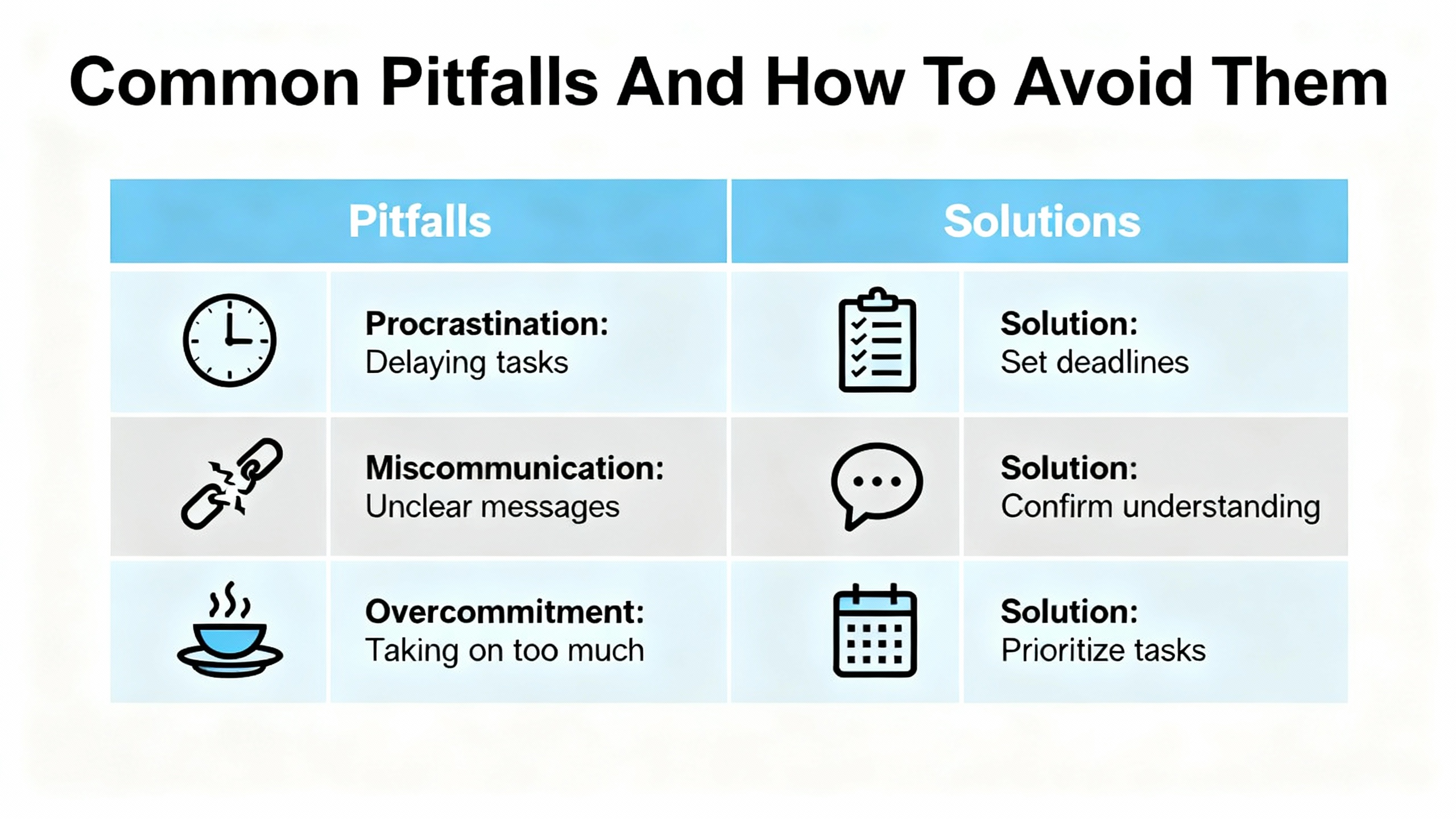

Several recurring pitfalls emerge from the cases and expert commentary in the research notes.

One pitfall is assuming a full OEM control replacement is always necessary when only incremental needs exist. TC&E warns that OEMs often recommend platform upgrades such as moving from Mark IV to Mark VIe even for small additions like a new hydraulic system or pressure switch. In at least one example, TC&E found ways to add steam augmentation logic to an existing Mark IV system without a wholesale upgrade, using engineers experienced in legacy logic. Owners should always explore whether recommissioning or partial modernization can address their requirements before accepting a complete platform change proposed by the OEM.

Another pitfall is neglecting field devices and wiring during upgrades. MD&AŌĆÖs recommissioning work revealed non-working dampers, battery charger issues indicated by buzzing noises, junction box problems affecting fire protection systems, non-working field devices, and incorrect wiring. TTSŌĆÖs experience at Valencia also underscored the value of fully loop checking each field device during a controls upgrade to uncover latent faults. A new control panel cannot deliver reliability if it is connected to degraded instruments, cabling, and auxiliary systems.

A third pitfall is ignoring the broader plant impact of turbine upgrades. The Combined Cycle Journal article on gas-turbine upgrades and their impacts on heat-recovery steam generators describes how increases in exhaust temperature and flow can overstress superheaters, reheaters, economizers, drum internals, and attemperators. Although that article focuses on hardware upgrades rather than control panels, it reinforces an important point: any substantial change to turbine operation or controls should be accompanied by a study of downstream equipment and balance-of-plant interactions, including how new control logic will manage transients and limits.

Improper start-up and shutdown procedures are another risk area highlighted by CallGTC. The article notes that incorrect procedures during these phases can contribute to overspeed events, especially if control logic and operator actions are not aligned. When controls are upgraded, training and clear procedures are as important as the hardware and software themselves.

Finally, environmental conditions during extended outages or layup periods are often underestimated. Power EngineeringŌĆÖs discussion of dehumidification strategies in turbine and generator maintenance shows how corrosion accelerates when relative humidity exceeds about forty percent and becomes exponential above roughly sixty percent, especially in the presence of industrial pollutants. Desiccant dehumidifiers and well-sealed work areas can prevent subtle corrosion of rotors, stators, and internal components during long outages or preservation periods, improving the long-term reliability of both new and existing control wiring and devices.

Is a control panel upgrade worthwhile if my turbine still starts most of the time?

Starting ŌĆ£most of the timeŌĆØ is not adequate when the unit is part of a power security strategy. Evidence from modernization projects reported in Power magazine shows that upgrading controls can raise starting reliability from roughly half of attempts to above ninety percent while also reducing nuisance shutdowns. Combined with new diagnostics and better visibility, that can justify the investment simply by avoiding a few major forced outages or contract penalties.

Is an OEM control system always safer than a third-party open system?

Safety depends more on implementation quality, testing, and lifecycle support than on whether the platform is OEM-branded. The Power Engineering article on open systems shows that closed OEM systems can, in some situations, force operators into unsafe workarounds when proprietary components fail. Third-party open systems, when designed and commissioned by experienced turbine specialists, can achieve equal or better safety while giving owners more control over diagnostics, spares, and training. The key is to choose a supplier with deep turbine control experience and a demonstrable track record.

How should I think about redundancy for my new control panel?

The Automation & Control Engineering Forum contributor suggests starting from operating mode. A unit required to run around the clock at high availability may justify triple modular redundant or dual redundant architectures so that most components can be replaced online. Peaking or backup units that can tolerate occasional forced outages may not need high redundancy and can avoid the complexity and higher spare parts burden. In both cases, proper maintenance and attention to diagnostic alarms remain crucial.

How do control panel upgrades interact with UPS and other power protection equipment?

While the research sources focus on turbine controls, practical projects should treat the control panel, its dc supply, and its trip circuits as part of the broader power protection system. New panels may draw different control power, require revised coordination with generator protection relays, or rely on faster communication with breaker and switchgear controls. A thorough upgrade plan will review UPS capacity, distribution, and protection settings to ensure the entire chain supports the new control architecture during start, normal operation, and emergency shutdowns.

As a reliability advisor, I suggest thinking about gas turbine control panel upgrades the same way you would think about replacing a critical UPS or static transfer switch. The goal is not just a newer box; it is a more observable, maintainable, and resilient power system. Whether you start with recommissioning, partial modernization, or a full open-architecture or OEM replacement, the strongest outcomes come when turbine controls, generator systems, protection, and power quality strategy are designed as a whole rather than as separate projects.

Leave Your Comment