-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In many plants I visit, the Yokogawa control system is the quiet success story in the background. Operators know the graphics by muscle memory, production runs day after day, and the cabinets sit on clean UPS power that nobody wants to touch. That familiarity is exactly why migrations get delayed until the system becomes a liability instead of an asset.

ISAŌĆÖs guidance on DCS upgrades highlights that legacy platforms feel comfortable but steadily accumulate risk: vendor support tapers off, replacement parts become scarce, software falls behind current operating systems, and integration with new technologies becomes harder. ARC Advisory Group makes a similar point: if a migration ends up as a simple like-for-like replacement, you have missed the opportunity to improve reliability, safety, and business performance.

From a power and reliability standpoint, the DCS is the decision-making brain that orchestrates how switchgear, UPS-backed feeders, inverters, and process equipment respond to events. When that brain rests on aging operating systems and unsupported controllers, every grid disturbance, transfer to generator, or UPS failure carries more risk than it should. A Yokogawa system replacement is therefore not just a software project. It is a reliability project that should be planned with the same rigor as a major power-system change.

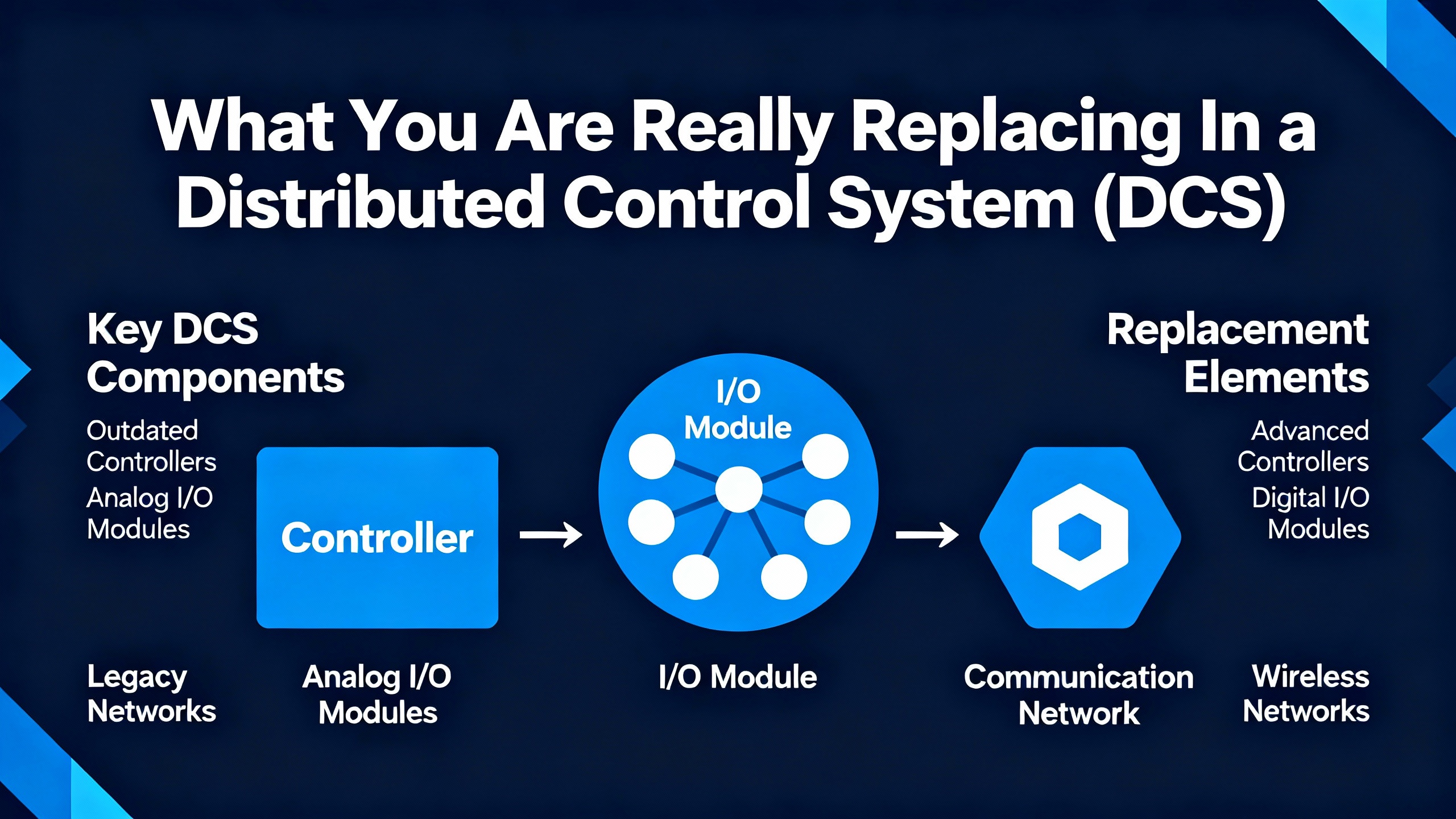

Before talking about migration paths, it helps to be precise about what ŌĆ£the DCSŌĆØ means in a Yokogawa context. ARC Advisory Group defines DCS migration as upgrading a legacy or installed control system to a current system while preserving valuable intellectual property, leveraging new platform capabilities, minimizing operational impact and cost, and enabling future business value. In practice, that involves several layers.

Yokogawa technical reports describe the Field Control Station, or FCS, as the controller node that performs input processing, control computation, logic operations, and output processing. In the CENTUM CS 1000 family, the FCS is built around hot-standby redundant CPU cards, redundant power supplies, and duplicated control and I/O buses. These FCSs share architecture and I/O modules with larger CENTUM CS systems, which simplifies mixed-system maintenance. The FCSs communicate with Human Interface Stations (HIS) and gateways over a VLnet control bus operating at 10 Mbps, with network spans on the order of a few hundred feet per coax segment and roughly a dozen miles when fiber repeaters are used.

The hardware is engineered for compactness, low power consumption, and maintainability. CPU redundancy is synchronous and hot standby, dual power supply cards feed both CPU and I/O nests, and VLnet and I/O buses are duplicated with automatic error detection and isolation. Only the main power distribution board and part of the CPU switching circuit are non-redundant. The FCS nests are fanless, support front-access hot-swappable cards, and mount in standard 19ŌĆæinch racks with up to five I/O nests. Power supplies are available for 100ŌĆō120 V AC, 220ŌĆō240 V AC, and 24 V DC, making integration with UPS and DC systems straightforward.

On newer Yokogawa platforms such as CENTUM VP, the system extends this hardware robustness with virtualization and advanced HMI. Yokogawa describes how virtualization decouples system software from physical hardware so multiple virtual machines can run on a single server. This allows hardware to be refreshed while software images are preserved, shortens migration and test periods, and clarifies maintenance boundaries between IT and OT. Operator stations use ergonomically designed graphics, high visibility color schemes, alarm management through a Unified Alarms and Conditions Server, and trend recording that supports both continuous and batch-type monitoring.

In other words, a ŌĆ£Yokogawa DCS replacementŌĆØ touches controllers, workstations, servers, networks, and data structures. The more clearly you understand that stack, the more deliberate you can be about what truly needs replacement and what can be retained or modernized.

| Layer | Typical Yokogawa elements | What a replacement may change |

|---|---|---|

| Field control and I/O | CENTUM FCS, I/O nests and modules | Controllers, I/O modules, redundancy scheme |

| Operator and engineering | HIS workstations, engineering stations, specialized keyboards | PCs, OS versions, HMI tools, virtualization |

| Servers and applications | Historians, Exaquantum, ExaOPC, batch and asset tools | Server hardware, OS, versions, licensing |

| Networks | VLnet or Vnet, plant Ethernet, WSUS update servers | Network hardware, addressing, security architecture |

| Power and environment | UPS-fed feeders, FCS power cards, HVAC, grounding | UPS capacity, feeders, distribution, room conditions |

Control Engineering and Plant Engineering note that process units often run decades longer than the 15ŌĆæyear lifecycle typically assumed for a DCS. They also highlight typical component lifetimes: field wiring may remain viable for around forty years, I/O and termination panels for about twenty years, controllers for fifteen years, operator displays for roughly eight years, and workstations for about five to six years. That mismatch is why many facilities are operating Yokogawa systems that are two or three generations behind current software.

Plant Engineering and TechWem describe several migration drivers that are especially relevant for Yokogawa owners. Hardware obsolescence and diminishing spare-part availability push risk higher every year. As older servers and workstations fall off the vendorŌĆÖs support matrix, security patches stop flowing or become difficult to validate. Meanwhile, the convergence of OT and IT and the rise of IIoT connectivity have erased the traditional ŌĆ£air gap,ŌĆØ which means older, unpatched systems become attractive targets.

Another driver is loss of in-house expertise. Many legacy Yokogawa systems carry decades of incremental changes, undocumented workarounds, and abandoned logic. As senior engineers retire, the tacit knowledge that explains ŌĆ£why it is wired that wayŌĆØ disappears. Plants then face an uncomfortable choice between running a black box on life support or tackling a structured migration.

Finally, modernization pressure is not only about risk. Modern Yokogawa DCS platforms and their peers support richer data structures and more open interfaces. Plant Engineering points out that modern DCSs unlock data for analytics, environmental reporting, asset management, predictive maintenance, and digital twins. From a power-systems angle, that means easier correlation between power quality events and process behavior, better disturbance analysis, and more confident use of advanced control strategies that depend on reliable data.

A real-world example comes from a Control.com discussion on migrating Yokogawa CENTUM VP from Release R4.02 to Release R6. The responder emphasizes that this is a major change rather than a minor revision. R4 is supported on Windows 7, whereas R6 requires Windows 10 or Windows Server 2016. That operating-system gap alone typically forces replacement of all servers, workstations, and HIS hardware.

The licensing model also changes. Releases R4 and R5 share a license structure, but R6 introduces a different scheme. Existing R4 or R5 licenses are migrated so that purchased features such as engineering tools, trending, and FCS expansions are retained. However, a new R6 license must be purchased based on the total physical and virtual I/O count. Yokogawa uses a software tool that scans the system for I/O points, FCSs, license keys, software versions, and patch levels so that license capacity is sized accurately and cannot be understated.

Companion software is part of the scope. The same forum response notes that Exaquantum and ExaOPC must be upgraded at minimum, and systems using UGS typically need new servers running Windows Server 2016. Sites that maintain their own WSUS servers for managing Windows updates must also migrate those update servers to the newer operating systems.

Interestingly, not all hardware is impacted equally. AFV10/30-series field control stations were reported as unaffected by the R4-to-R6 upgrade in that case, even though the answer did not address every controller type. This underlines the point that a Yokogawa migration may involve a complete renewal of servers and HMIs while leaving certain FCS hardware in place, as long as it remains supported and aligned with the new software baseline.

The same practitioner notes that having a Yokogawa lifecycle (LCA) agreement is beneficial and that the recommended starting point is a discussion with the local Yokogawa systems manager. That engagement typically involves several calls and at least one site visit. Preparation alone commonly takes about six months, and total expenditure scales with control-system size and the number of components changed.

From a power and reliability perspective, this example illustrates something important. You can refresh the computing platform and applications while keeping proven FCS hardware that already sits on well-engineered UPS feeds and redundant power cards. Alternatively, you can treat the migration as the moment to modernize everything, including the power infrastructure feeding the DCS. Either way, you need enough lead time to engineer and test the changes instead of rushing under crisis conditions.

Once you decide to move away from a legacy Yokogawa release or platform, the next question is how aggressively to change the control logic and graphics. HargroveŌĆÖs discussion of DCS migrations presents two primary strategies: one-for-one replication and from-scratch redesign. Both begin with reverse engineering, which is mandatory for any serious migration. Engineers study the legacy Yokogawa software, hardware, and documentation, and interview operations staff to understand the true control philosophy and required functionality.

One-for-one migration aims to replicate every loop, wire, piece of code, and logic structure from the legacy system into the new platform. Automated conversion tools can help with simple to moderately complex schemes and reduce engineering effort when there is strong similarity between old and new configuration strategies. This approach is well suited when the existing graphics layout is mostly retained, the system is dominated by low-level points and simple PID loops, and the legacy and new system architectures map cleanly.

However, the same article points out significant downsides. One-for-one conversion effectively freezes the clock on your legacy logic, missing opportunities to simplify, adopt modern functions, and reduce controller loading. Migrating unused or ŌĆ£deadŌĆØ code increases cost, schedule, and startup troubleshooting effort. Startup may be more difficult because you are carrying forward thirty years of design history, including inconsistencies and one-off solutions.

By contrast, from-scratch migration redesigns the control logic, hardware, and narratives from the ground up. The goal is to optimize process performance, exploit modern platform capabilities, and eliminate unnecessary complexity. Hargrove notes that equivalent functionality might be implemented with about ten function blocks instead of one hundred legacy blocks. The result is a leaner system that is easier to troubleshoot, faster to optimize, better documented, and less expensive to maintain over its life.

The trade-off is clear. From-scratch design demands more front-end engineering and tighter collaboration with operations and process engineering. One-for-one conversion is sometimes faster to configure but can lock in outdated practices. In practice, many successful Yokogawa migrations use a hybrid approach: one-for-one conversion where the legacy design is sound, coupled with redesign of problem areas, dead code removal, and HMI modernization.

| Configuration strategy | Typical use case | Main benefits | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-for-one | Simple loops, stable graphics, strong similarity between systems | Shorter engineering, automated conversion possible | Carries dead code, misses modernization opportunities |

| From-scratch | Complex or poorly documented systems, desire for optimization | Leaner logic, easier troubleshooting, better long-term cost | Higher up-front effort and need for deep domain input |

ISAŌĆÖs ŌĆ£ten essentialsŌĆØ for DCS upgrade and migration underscore that the highest-risk period is the installation phase, especially the cutover from the old to the new system. During cutover, every field instrument, valve, motor controller, network segment, cable, and I/O card connection must transition correctly. Any error can cause extended downtime or unsafe conditions.

To reduce that risk, ISA and multiple engineering sources emphasize detailed front-end loading, or FEL. FEL should be completed well before any cutover activities begin and must actively involve process engineers, maintenance teams, and the chosen automation provider or system integrator. TechWem adds that clear migration objectives and scope are essential: you should decide whether you are replacing primarily for obsolescence or also to add functionality, cybersecurity, and integration. Goals can be framed around reducing unplanned downtime, improving operator efficiency, aligning with standards such as ISA/IEC 62443, and integrating data with enterprise systems.

A solid FEL phase starts with an as-is analysis. That means reviewing and validating P&IDs, control narratives, loop diagrams, network drawings, hardware layouts, configuration backups, alarm philosophy, and maintenance logs. TechWem recommends systematically identifying gaps and inaccuracies rather than accepting legacy drawings at face value. Hardware and network audits should inventory controllers, I/O, servers, workstations, and network devices, along with their location, firmware, and current loading. Configuration analysis should examine control strategies, custom code, HMI graphics, historian tags, alarms, and external integrations.

Equally important is capturing operational realities. Both TechWem and Logical SystemsŌĆÖ specialty chemical plant case study stress the value of talking to operators, maintenance technicians, and engineers about pain points, workarounds, and unofficial practices. These conversations frequently reveal issues that never made it into the documentation but will determine whether the migrated system actually works for the people who rely on it.

Early, systematic risk analysis during planning and installation lets you address safety, expected downtime, resource availability, network traffic, data integrity, and cybersecurity while options are still open. Plant Engineering recommends applying a disciplined front-end loading process to define the desired future state, align migrations with maintenance turnarounds, and reduce scope changes and schedule slips. A risk register with mitigation actions, clear roles, and decision thresholds turns that analysis into a practical tool rather than a paper exercise.

Testing is non-negotiable. ISA, TechWem, and Plant Engineering all emphasize the combination of Factory Acceptance Testing and Site Acceptance Testing. FAT at the vendor or integrator site validates that hardware integration, control logic, HMI graphics, alarming, and communications meet requirements before anything ships. SAT then verifies installation quality, wiring, connectivity, loop checks, and functional performance in the actual plant environment. For Yokogawa upgrades, that usually means exercising FCS redundancy, historian and ExaOPC connectivity, alarm routing, and failover scenarios while the system is still in a controlled state.

Choosing how to execute the cutover is as important as choosing what to replace. ARC Advisory Group outlines several options and their trade-offs.

Total system replacement during a planned turnaround replaces the entire control system in one major outage. When there is a suitable time window, the process type allows it, and the supplier or integrator has strong experience, this can be the fastest and sometimes least costly approach. Downtime is limited to a single event, redundant labor is reduced, and you emerge with a single, current-generation system that simplifies lifecycle support and lowers total cost of ownership. The downside is that the stakes are high; if the new system is not ready, schedule pressure and restart risk increase quickly.

Phased migration is often chosen when the hardware infrastructure, wiring, and I/O are deeply embedded in the plant and wholesale replacement is difficult or cost prohibitive. In a phased approach, only those components that must be replaced are upgraded at each step. This reduces immediate risk and capital outlay but lengthens the migration horizon and introduces interfaces between new and old systems that must be managed carefully. TechWem notes that large sites frequently require phased execution by process unit or area simply because they cannot be taken down all at once.

ARC describes hot swap migration as replacing DCS components while the production process is running. Hot swap minimizes the time that the process is not producing, which can be attractive for continuous operations. However, it carries higher risk if not planned and executed carefully. Thorough preparation, automated conversion for databases and graphics, and meticulous testing are mandatory. Conversion of legacy sequence code is particularly tricky and often requires supplier-specific strategies.

The opposite extreme is a downtime migration in which all changes to hardware and software occur while the process is stopped. This removes the risk of inadvertently tripping the plant mid-run but introduces a hard deadline. The new system must be fully functional within the allotted shutdown window, and there is frequently no easy way back once the old system is removed. TechWem also describes parallel operation strategies where a new system is run alongside the old with temporary marshalling. These approaches minimize switchover risk at the cost of temporary additional hardware and engineering effort.

YokogawaŌĆÖs own FCS Online Upgrade solution, promoted in a recent video, adds another dimension: it allows certain system software upgrades to be performed while maintaining continuous process control, eliminating the need for prolonged full-plant shutdowns for those tasks. This kind of online upgrade supports regular updates for cybersecurity and functionality while maintaining plant availability and productivity. In practice, most owners use a combination of approaches: online upgrades and hot swaps for incremental changes, phased or total replacement for structural platform changes. The key is aligning the cutover strategy with process risk tolerance, power-system flexibility, and the realities of maintenance windows.

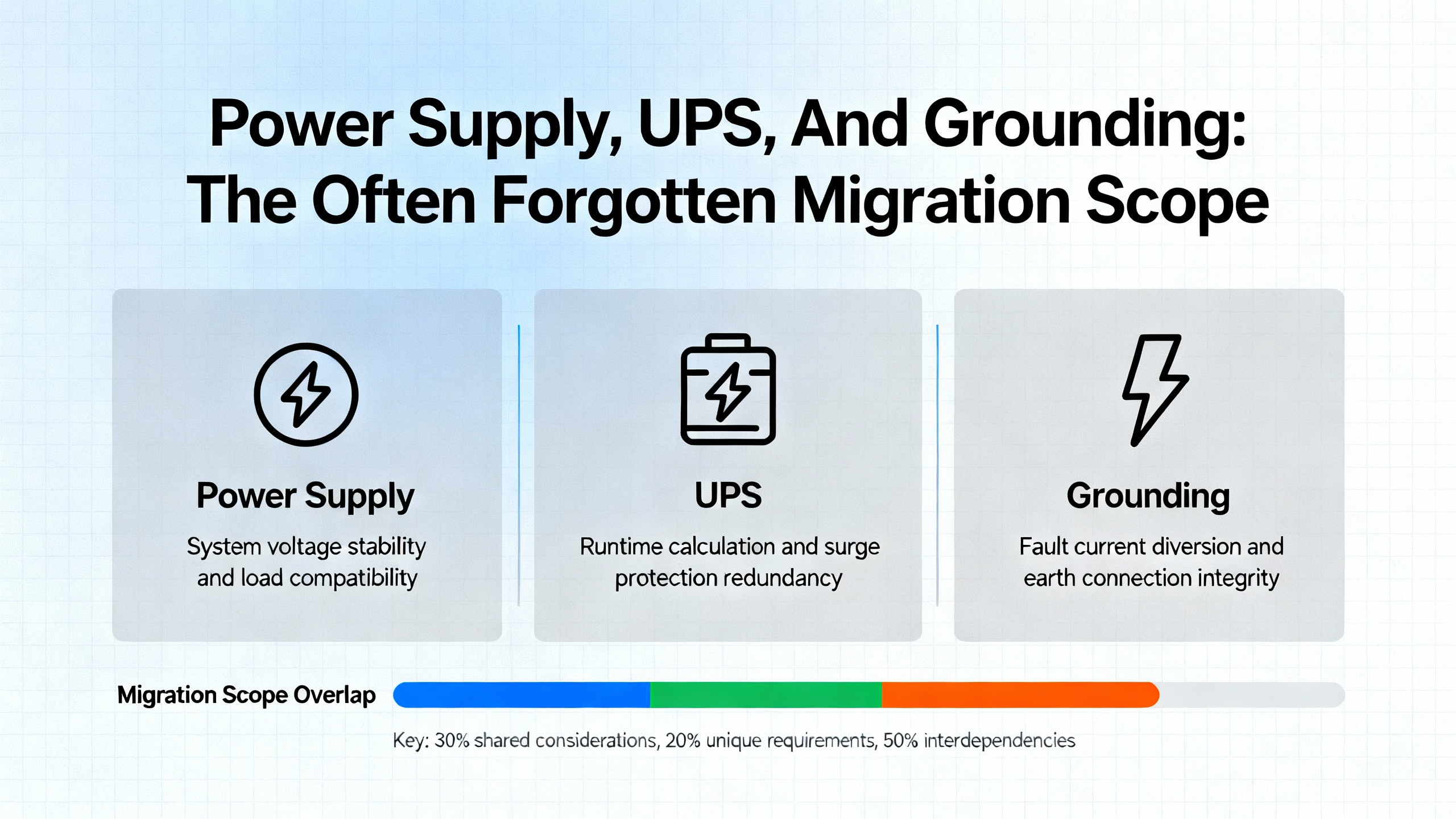

As a power-system specialist, I have seen many migration plans that devote hundreds of pages to control logic and graphics but only a few lines to the power that keeps the DCS alive. YokogawaŌĆÖs own DCS maintenance procedures underline how critical that electrical foundation is.

Preventive checks include verifying AC voltages between line and neutral, line and earth, and neutral and earth on left and right feeders from the UPS to the DCS panels. DC power quality is checked on both feeders and at analog and digital terminal boards to confirm that all field I/O and electronics receive stable voltages. Proper grounding and earthing of panels, including the quality of welds and dedicated instrument earths, are explicitly required to minimize electrical noise, ground loops, and fault hazards. Environmental factors such as fan operation, filter cleanliness, room temperature, relative humidity, and dust ingress are monitored because they directly affect electronics longevity.

On the controller side, Yokogawa prescribes quarterly checks of CPU battery expiry dates and voltages, along with verification of PW482 power-module outputs at all nodes to ensure that redundant DC distribution remains healthy. For HIS and server PCs, asset and configuration data such as station numbers, network cards, IP addresses, operating systems, and service-pack levels are recorded and reviewed.

A DCS migration is the ideal time to formalize these practices into the project scope. When you plan a Yokogawa replacement, include explicit tasks to review UPS and inverter capacity, distribution paths to FCS power cards, breaker coordination, and grounding schemes. Confirm that redundant feeds are truly independent, that UPS autonomy is appropriate for the new hardware footprint, and that protective relays and transfer schemes will not introduce unexpected disturbances during cutover. By tying the power audit to the migration, you reduce the chance that a beautifully engineered new DCS suffers its first major outage due to a preventable power issue.

Logical SystemsŌĆÖ specialty chemical plant DCS upgrade illustrates how much success depends on people rather than tools. The project started with time spent alongside the operations crew: maintenance technicians, plant operators, and others who live with the system every day. The team documented their issues and workflows and recorded functional requirements in language that matched real operations, not just P&IDs. Drawings of legacy equipment were created and field-verified so that plant details were accurate and up to date.

Stakeholder engagement extended across functions. Process engineers provided input on required functionality and control strategies. Operators shaped the HMI look and feel, including layout and customization requests that would make their work easier and safer. Electrical and instrumentation and maintenance groups focused on design for reliability and the use of standard parts that could be stocked and replaced quickly. Operations scheduling weighed in on downtime windows and commissioning plans so that migration steps fit production reality. The underlying principle was simple: prioritize solutions that make sense for the people running the system, not just for the controls engineers.

YokogawaŌĆÖs own article on system integrator success presents a complementary four-step model: Identify, Create and implement, Operate, and Sustain and improve. The first step is to identify challenges through collaboration and coŌĆæinnovation, including gaps between production plans and actual performance, inconsistent quality, and the need to maximize output while minimizing energy use. Importantly, the article stresses benchmarking against industry best practices, such as uptime levels, rather than only internal history.

Domain knowledge and industry experience are repeatedly emphasized as critical criteria when selecting a system integrator. Engaging an integrator expert in power generation to solve a refineryŌĆÖs problems, for example, is unlikely to succeed. The recommendation is to insist on integrators with extensive expertise in similar processes and plants and to verify references through phone calls or site visits.

During creation and implementation, integrators can bring proven solutions such as remote performance monitoring with periodic reviews, support for adjusting production plans in response to external factors, consolidation of multiple quality-related process values into single indices, pattern analysis of batch data, advanced process control to optimize production, and soft sensors that infer real-time product quality. After commissioning, keeping the integrator engaged for several months allows fine-tuning of operations and thorough training of plant personnel. Long-term success then depends on internal staff sustaining and improving the system, with the integrator remaining as an on-call resource in the value-generation cycle.

Not every Yokogawa owner needs or can justify a full rip-and-replace project. Control Engineering outlines three broad modernization strategies that apply directly here: operation-level upgrades, partial migration that reuses infrastructure, and full DCS replacement.

Operation-level upgrades may focus on operator and engineering stations while retaining existing controllers and I/O. Upgraded HMIs, engineering tools, and historians can deliver better alarm management, trending, and analytics with minimal impact on field wiring and FCS cabinets. This incremental approach reduces downtime and shutdown risk and can often align with existing maintenance and budget cycles. Its success depends on strong interoperability between the legacy Yokogawa hardware and the new software components.

Partial migration reuses existing infrastructure such as field wiring, termination panels, and sometimes even I/O nests while replacing controllers, servers, and workstations. For owners of Yokogawa FCS hardware that remains supported, this is an attractive route, especially when combined with virtualization. CENTUM VPŌĆÖs virtualization capabilities allow new virtual machines to be commissioned on fewer physical servers, and hardware can be updated with less disruption to running software.

Full replacement is warranted when the plantŌĆÖs remaining lifetime exceeds the DCS lifecycle, and goals include performance improvement, cost reduction, and adoption of new technologies. In this scenario, some owners look beyond traditional vendor architectures to open process automation. Control Engineering notes that open process automation, based on open standards and modular, plug-and-play design, allows equipment from multiple vendors to interoperate more freely, enables easier integration of legacy systems with new technologies, and eases component-by-component updates without full plant shutdowns. It also accelerates adoption of innovations such as advanced analytics and embeds modern cybersecurity practices by design.

Data migration is another dimension that deserves explicit treatment. QlikŌĆÖs data migration primer distinguishes between database, storage, business process, application, and cloud migration. A Yokogawa DCS project can touch all of these: configuration and historian databases, storage platforms, MES and ERP integrations, and sometimes a shift toward private or public cloud for analytics. Treating data migration as its own workstream, with its own testing and rollback plans, is essential to maintaining data integrity through the transition.

| Approach | Typical scope | When it fits best |

|---|---|---|

| Operation-level upgrade | HMIs, engineering tools, historians | When controllers are supported and risk appetite is low |

| Partial migration | Controllers, servers, workstations, reuse wiring/I/O | When infrastructure is sound but platform is obsolete |

| Full replacement | Controllers, I/O, networks, HMIs, servers | When long plant life and major performance gains are targeted |

| Open process automation | Modular, multi-vendor architecture, new control stack | When flexibility and long-term interoperability are priorities |

Pulling these threads together, a practical roadmap for a Yokogawa system replacement starts with strategy rather than hardware. ARC advises treating migration with the same rigor as initial control-system selection and embedding it in a continuous improvement process. In concrete terms, that means aligning your OT strategy, including the DCS, with business objectives such as safety, availability, energy efficiency, and digitalization.

Next, use FEL-style planning to define migration objectives and scope. Decide whether your primary driver is obsolescence, functionality, cybersecurity, integration, or some combination. Determine which units, control loops, operator stations, and network segments are in scope and which must be left for a later phase. For many sites, phased execution by unit is the only realistic option.

Then invest time in an honest as-is assessment and stakeholder engagement. Validate drawings, audit hardware and software, interview operators and maintenance staff, and catalogue pain points around alarms, power events, and restart behavior. Treat the DCS as part of the facilityŌĆÖs protection and energy-management ecosystem, not a separate island. Include UPS, inverters, switchgear control, and protection I/O in your inventory and risk register.

With that foundation, work with Yokogawa and, where appropriate, an independent integrator to choose your migration and cutover strategies: from-scratch or one-for-one configuration, total or phased replacement, hot swap, downtime, or parallel operation, and the degree to which you will use online FCS upgrades and virtualization. Build a detailed execution plan that includes FAT and SAT, resource planning, training, and power-system readiness checks.

Finally, treat commissioning not as the end but as the beginning of a new lifecycle. Keep the integrator engaged through early operations, track key performance indicators such as uptime, nuisance trip rates, and power-related incidents, and schedule regular reviews of both the control and power systems. Combine YokogawaŌĆÖs lifecycle services with disciplined internal maintenance so that monthly power checks, quarterly controller health checks, and periodic cybersecurity and data-migration reviews are standard practice, not emergency actions.

In the CENTUM VP R4-to-R6 example reported in a user forum, preparation commonly took about six months before the actual cutover, and total effort scaled with system size and the number of components changed. That timeline included vendor engagement, site visits, hardware and software scoping, and license sizing. Complex plants or those pursuing from-scratch redesign should expect at least that level of lead time.

In the same case, AFV10/30-series field control stations were reported as unaffected by the R4-to-R6 upgrade, even though servers and workstations had to be replaced to meet new Windows requirements. More generally, whether you can retain existing FCS hardware depends on its support status, compatibility with the new software release, and your long-term lifecycle strategy. A detailed review with Yokogawa and a lifecycle agreement can clarify which modules remain viable and for how long.

Yes, but with important qualifications. ARC, TechWem, and YokogawaŌĆÖs own materials describe options such as hot swap migration, phased migration, parallel operation, and YokogawaŌĆÖs FCS Online Upgrade, which can apply certain system software updates while maintaining process control. Each option carries different risk, cost, and complexity. A careful risk assessment, combined with extensive offline testing and strong UPS-backed power integrity, is essential before relying on any strategy that avoids a full shutdown.

In my experience, the most successful Yokogawa replacements treat the DCS, the power system that feeds it, and the people who operate it as a single reliability ecosystem. When you design your migration with that ecosystem in mind, you can modernize safely, protect uptime, and build a platform that supports the next decade of plant performance.

Leave Your Comment