-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In industrial and commercial facilities, Siemens drive systems, soft starters, UPSs, and other motor control gear have quietly become part of the critical power backbone. When a key drive, inverter, or control module fails, production often stops, and power protection schemes are compromised. At that point, the only number that really matters is how long it takes to get the right replacement part installed, tested, and back in service.

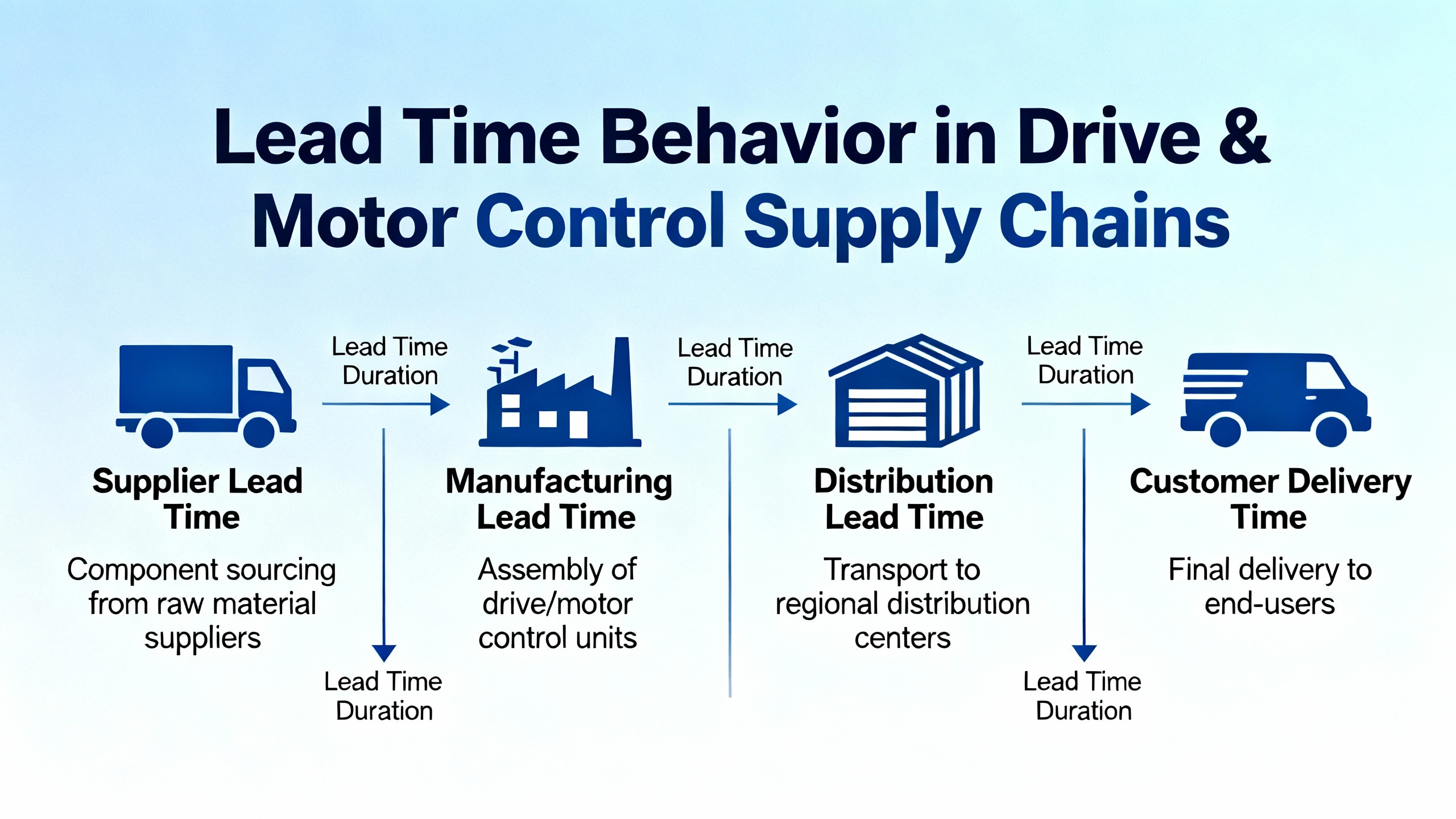

That number is lead time. Investopedia describes lead time as the total duration from the start to the end of a process, covering preŌĆæprocessing, processing, and postŌĆæprocessing activities. In a power and motor control context, that spans everything from your internal requisition through SiemensŌĆÖ or a distributorŌĆÖs processing, factory or warehouse handling, and freight, all the way until the part is on your dock and ready to install.

Manufacturing specialists such as CAI and Investopedia highlight that lead time is not one thing; it is a bundle of closely related intervals. Customer lead time stretches from order to receipt. Material or supplier lead time covers the time to obtain raw materials and components. Production lead time reflects the actual manufacturing or configuration work. Cumulative lead time is the entire chain end to end. For a maintenance manager looking at Siemens drive parts, these categories show up as the time to raise an internal order, the OEMŌĆÖs or distributorŌĆÖs internal cycle to pick, build or configure, and the transportation delay from their facility to yours.

The research consistently shows that shorter, more predictable lead times increase customer satisfaction, reduce inventory holding costs, and improve cash flow and operational efficiency. In a powerŌĆæcritical plant, that ŌĆ£customerŌĆØ is your own operations team and, ultimately, your production lines and tenants or patients. Long or unpredictable lead times are not just a commercial annoyance; they directly threaten uptime.

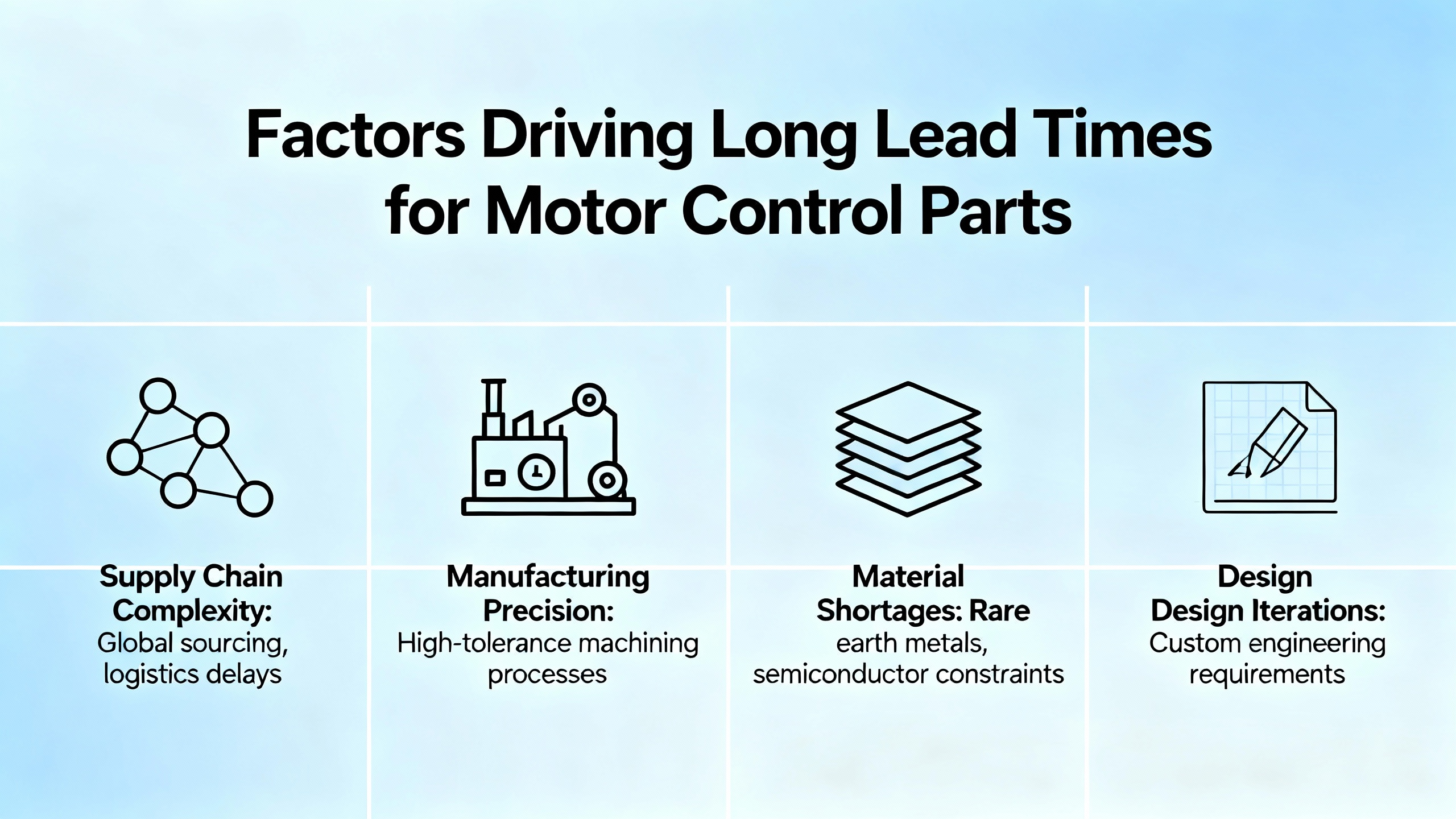

Although the research notes do not name Siemens specifically, they describe patterns that apply to any global OEM supplying complex, configurable equipment and spare parts. Manufacturing lead time, according to CAI and Umano, spans material procurement, production, assembly, testing, packaging, and shipment. Each of those stages can add days or weeks when you are dealing with specialized circuit boards, IGBT modules, control cards, or engineered motor control assemblies.

Several drivers dominate lead time in this environment. Supplier reliability and inventory management determine whether all necessary components are on hand when an order for a drive part enters the system. Production capacity and process complexity dictate whether Siemens or a contract manufacturer can insert your order into an existing flow without causing bottlenecks. Change orders and customization, transport performance, quality issues and rework, and demand fluctuations all add variability, as highlighted by CAIŌĆÖs list of ten leadŌĆætime drivers.

Transport itself has become a structural risk. CMiC Global describes how transport delays are no longer rare events; they are recurring disruptions that undermine project schedules, inventory strategies, and contracts. LearnAboutLogistics adds that cumulative international lead times can easily run beyond ninety days once port handling, consolidation, and lastŌĆæmile delivery are considered, even when transit time at sea is only a fraction of that. When the drive part you need is on another continent and infrastructure is strained, those same dynamics apply.

On top of that, lead time is not static. LearnAboutLogistics emphasizes that lead time depends on load. When incoming orders exceed available capacity slots at factories, warehouses, or logistics providers, quoted lead times stretch and become more variable. From a power systems perspective, this means that the lead time you heard during a calm period may be badly wrong once a regional surge in orders hits, whether that is due to a retrofit campaign, a standards change, or a major outage in your sector.

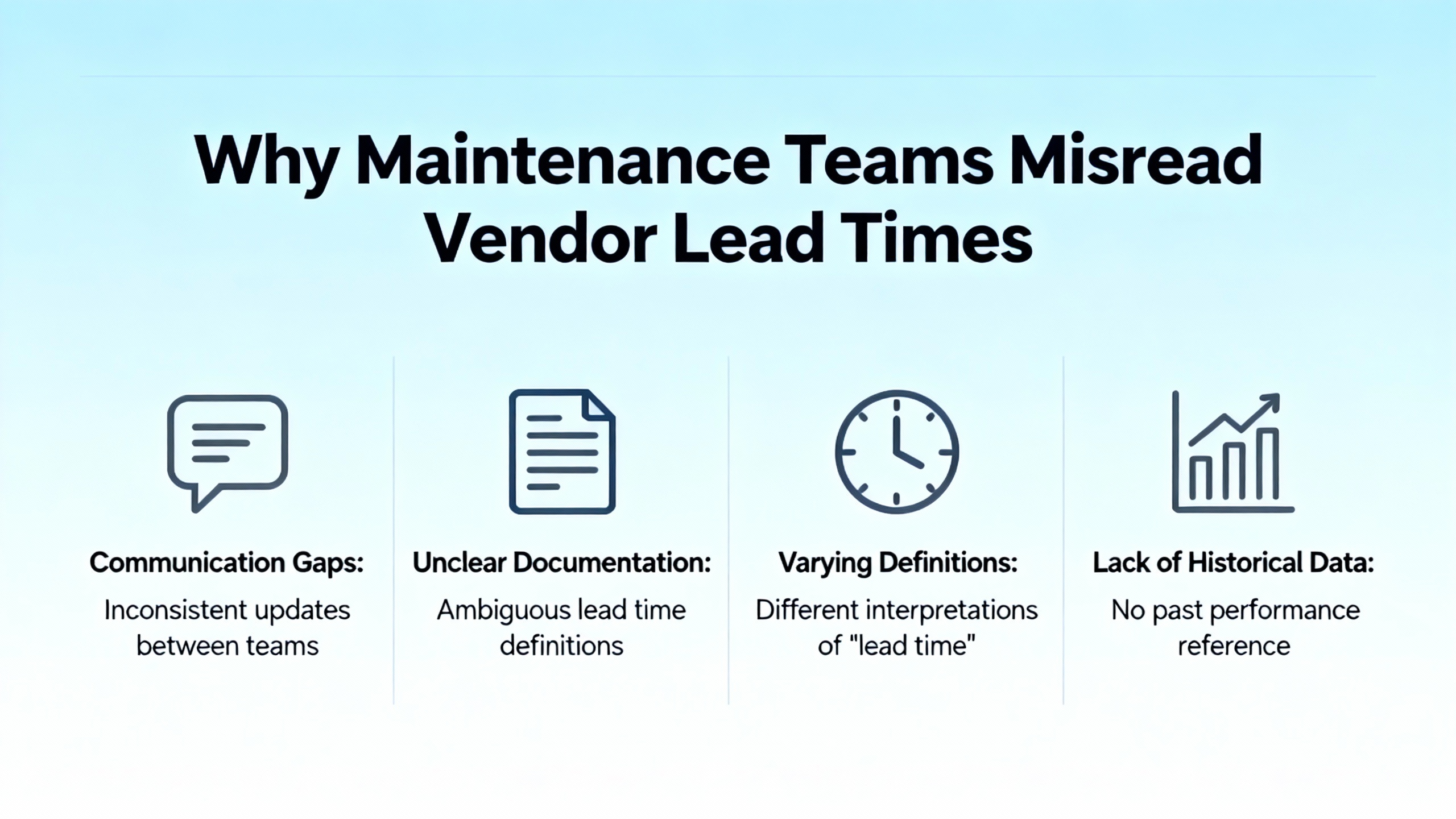

In power and automation projects, I consistently see a gap between how maintenance teams think about lead time and how manufacturers quote it. Mathison Manufacturing notes that a common misconception is to equate lead time only with shopŌĆæfloor production time. In reality, the upstream phases such as design review, procurement of special materials, and internal approvals, plus downstream services like assembly, testing, finishing, and packaging, often dominate the calendar.

Another complication is inconsistent definitions across suppliers. Mathison points out that one manufacturer might define lead time as ŌĆ£time to ship,ŌĆØ while another describes ŌĆ£time through productionŌĆØ and leaves shipping as an extra, sometimes tenŌĆæday, leg. When someone tells you a replacement drive control board is ŌĆ£six weeks,ŌĆØ you must know whether that is six weeks until a truck leaves their dock or six weeks until it arrives at your site and clears receiving.

The same source recommends asking for a phaseŌĆæbyŌĆæphase breakdown. For drive and motor control parts, that means separating prototype or engineering review if any, production or configuration, any finishing or custom firmware steps, assembly or testing, and shipping. Without that breakdown, your internal ŌĆ£motor control delivery scheduleŌĆØ is built on an ambiguous number that different stakeholders interpret in different ways.

Investopedia and Logistics Bureau both stress that simply measuring and clearly communicating lead times is a major step forward. Even if you are not yet reducing lead time, placing a reliable number against each Siemens drive part and ensuring everyone shares the same definition allows you to set realistic expectations, plan maintenance windows, and avoid surprise outages.

Lead time is sometimes treated as a procurement metric, but the research shows it is central to reliability and profitability. CAI notes that shorter and more predictable lead times support onŌĆætime delivery, lower inventory, better cash flow, and smoother production. In power and motor control, ŌĆ£onŌĆætime deliveryŌĆØ translates directly into reduced downtime risk and more predictable maintenance execution.

Umano cites a striking estimate: about forty percent of industrial resources are wasted due to bottlenecks, adding up to roughly twelve trillion dollars of losses worldwide. In motor control supply chains, those bottlenecks may sit in a single factory that assembles a specialized drive component, or in a congested transport corridor that most shipments must traverse. If you have a mediumŌĆævoltage drive down and you are waiting for one critical card, that bottleneck becomes painfully visible on your plant floor.

Milliken points to another dimension that matters for power system reliability: equipment uptime. A study referenced in their work found average machine uptime at only about sixtyŌĆæseven percent of scheduled time. For power and automation systems, poor maintenance and reactive repair behaviors turn lead time into a double penalty. You wait a long time for parts, and once they arrive, you discover hidden equipment issues that extend the outage further because preventative maintenance and early fault detection were not in place.

LearnAboutLogistics and Logistics Bureau both emphasize that lead time variability is as damaging as sheer duration. Long lead times that are stable can be treated like a ŌĆ£floating warehouse,ŌĆØ planned and buffered for. Unstable lead times undermine your ability to respond to demand and to schedule work, which typically triggers overŌĆæordering, excess safety stock, or the infamous ŌĆ£Lead Time SyndromeŌĆØ in which planners continually lengthen assumed lead times, customers place larger and earlier orders, and the system becomes both slower and more volatile.

For Siemens drive parts, that volatility shows up as unexpected slips in promised ship dates, partial shipments, and rushed changes to maintenance schedules. The result is often overtime, emergency workarounds, and, in some cases, running without the desired level of power protection or redundancy. All of these have a cost well beyond the purchase price of the part.

The research briefs converge on a set of root causes that explain why Siemens and similar OEMs sometimes quote long lead times for drive and motor control components. Supplier reliability is near the top. CAI and Umano stress that poor or unstable suppliers, late shipments, customs delays, and partial deliveries are critical risks. For motor control parts, that may mean a single component supplier for power semiconductors or control processors that cannot meet demand, forcing staggered or delayed production.

Inventory management practices are another major driver. When inventory systems lack realŌĆætime accuracy, or reorder points are poorly tuned, stockouts of key items become frequent. CAI advocates for automated reorder points and realŌĆætime inventory management as a way to avoid production stoppages. In a powerŌĆæsystems setting, that principle applies both at the OEM and at your site. If your own store does not have a reliable picture of which drive spares are on the shelf, you cannot trust your maintenance plan.

Production capacity and process complexity matter as well. Complex items with many options, tight tolerances, or specialized testing requirements take longer to build and validate. Mathison notes that highŌĆæmix, lowŌĆævolume environments, custom enclosures, and intricate assemblies all extend lead time. Advanced analytics and Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES), as described by Plex and Umano, can mitigate this by dynamically adjusting schedules and rerouting work when a machine fails, but only if they are implemented and well integrated.

Transportation and logistics performance has become perhaps the most visible contributor. CMiC describes how transport timing now systematically affects jobsite readiness and contract performance, rather than acting as a purely random risk. LearnAboutLogistics extends this idea by distinguishing between transit time and the rest of the cumulative lead time. Many of the most variable and problematic activities happen between order entry and departure from the origin port or warehouse.

Finally, quality issues, rework, and regulatory or compliance steps can add considerable time. CAI advises robust quality management and proactive planning for testing and compliance to avoid failed inspections and regulatory delays. For drive parts used in safetyŌĆæcritical power applications, compliance with grid codes, safety standards, and customer specifications can be substantial. If those steps are not built into the leadŌĆætime model and scheduled effectively, they will show up as disappointing delays just when you need a part most.

The good news from the research is that lead time is highly manageable when you treat it as a process rather than a mysterious fixed value. Investopedia outlines lead time factor categories covering procurement, manufacturing, and shipping delays. CAI and Umano both emphasize breaking lead time down into preŌĆæprocessing, processing, and postŌĆæprocessing, or into material order time, production time, and customer lead time.

In practice, that means starting with a simple discipline: for each critical Siemens drive or motor control spare, define lead time explicitly as ŌĆ£order to ready for installation,ŌĆØ then ask your suppliers to decompose their number. You may discover that a large fraction of the delay is not factory build time but internal processing and transport.

Once you have that breakdown, you can target specific components. Umano presents comparative data showing typical leadŌĆætime reductions of about ten to thirty percent from supplier collaboration, five to fifteen percent from inventory optimization, twenty to forty percent from process automation, five to twenty percent from better demand forecasting, and five to fifteen percent from transportation optimization. These are general figures, but they illustrate that you can choose an action set that fits your situation and budget rather than hoping for a single magic fix.

Modern software can support this new discipline. Plex describes how a wellŌĆæintegrated MES with a centralized workŌĆæcenter list, production tracking, capacity planning, and electronic tracking of maintenance and spareŌĆæparts usage improves visibility and performance analysis. TractianŌĆÖs view of Production Planning and Control casts it as the ŌĆ£brainŌĆØ of operations, integrating production, procurement, inventory, and logistics so machines do not sit idle, stockouts are avoided, and deliveries remain on schedule. When you connect your power maintenance planning, spareŌĆæparts inventory, and supplier interfaces into such a system, lead time becomes a living parameter you can monitor and improve.

Inventory is where many powerŌĆæsystem organizations either overspend or take unwise risks. Investopedia notes that vendorŌĆæmanaged inventory and justŌĆæinŌĆætime approaches can reduce stockouts and lead time, while CAI highlights realŌĆætime inventory and automated reorder points as key enablers of short, predictable lead times.

For Siemens drive and motor control parts, the right strategy is rarely ŌĆ£keep everythingŌĆØ or ŌĆ£keep nothing.ŌĆØ A more effective approach is to segment the installed base and apply different stocking strategies by criticality and leadŌĆætime profile. Critical drives feeding entire production lines or hospital imaging suites deserve a more conservative policy than nonŌĆæcritical HVAC drives with easy workarounds.

Mathison recommends blanket orders and Kanban or justŌĆæinŌĆætime replenishment for manufacturers seeking to manage cost and lead time together. That concept translates well to spares. For moderately critical items with reasonably predictable failure rates, you can work with Siemens or a distributor to set up blanket orders or supplierŌĆæheld stock, backed by clear leadŌĆætime guarantees. The parts remain off your books until consumed, but you reduce exposure to sudden leadŌĆætime spikes.

LearnAboutLogistics warns that when lead times are variable, lean and justŌĆæinŌĆætime models can break down, forcing firms into either low stock with emergency orders and premium freight or overstocking that clogs space and capital. For truly critical power assets where leadŌĆætime variability is high, it is often rational to ŌĆ£break the rulesŌĆØ of lean and carry what looks like excessive inventory. The point is not to reject lean thinking, but to align it with the realities of your risk tolerance and the nature of the supply chain.

Several sources stress that choosing suppliers purely on unit cost is a recipe for poor leadŌĆætime performance. Umano and CAI both argue that speed and reliability should be frontŌĆærank criteria, alongside cost. In my own work with industrial power users, I have seen many cases where a cheap, slow channel looks attractive until the first serious failure, after which the true cost of extended downtime becomes apparent.

Effective collaboration starts with transparency. Share demand forecasts and installedŌĆæbase information with Siemens or your drive distributor at an appropriate level of detail. CAI notes that demand forecasting supports optimized inventory levels and smoother production. For drive parts, a clear view of expected retrofit campaigns, planned outages, and known obsolescence issues allows the OEM to stage materials and capacity ahead of time.

Strategic supplier selection also means looking at geographical footprint and resilience. Logistics Bureau and LearnAboutLogistics both caution that long international lanes introduce regulatory, customs, weather, and capacity risks that are only partially controllable. When you can source critical drive parts through regional hubs or local inventory, even at a modest price premium, you trade some cost for a substantial reduction in both lead time and its variability.

Contracts and commercial structures matter as well. UmanoŌĆÖs supplyŌĆæchain guidance includes building longŌĆæterm partnerships around guaranteed lead times, joint inventory management, and contingency plans. For Siemens drive parts, that can mean framework agreements that define target lead times by part category, escalation paths when those targets are threatened, and structured options such as consignment stock at your facility or at a nearby warehouse.

Lean manufacturing tools like justŌĆæinŌĆætime production and Kanban are central in the leadŌĆætime literature. Umano describes how they minimize inventory, cut waste, and enable realŌĆætime adjustment to demand. MRPeasy and PlanetTogether show how advanced planning and scheduling, finite capacity scheduling, and pull systems like Kanban and CONWIP reduce workŌĆæinŌĆæprocess and keep bottlenecks visible.

It is tempting to apply these ideas aggressively to Siemens drive parts and other motor control spares, aiming to carry almost nothing and rely on a fast, responsive supply chain. But LearnAboutLogistics and Logistics Bureau both caution that variable lead times and external shocks can quickly break this model. When ocean freight slips, customs rules change, or a key supplier faces a labor dispute, a justŌĆæinŌĆætime system with no buffers turns into a justŌĆætooŌĆælate system.

A practical compromise is to use lean techniques to eliminate internal waste while retaining deliberate buffers against external variability. That means cleaning up your own requisition processes, standardizing parts where feasible, using accurate inventory data, and automating reorder triggers. At the same time, you hold explicit safety stocks or time buffers on those Siemens drive parts whose upstream leadŌĆætime variability is high and whose failure would have severe consequences.

MillikenŌĆÖs threeŌĆæphase approach of engaging, educating, and empowering frontline staff is instructive here. When operators and technicians understand the rationale behind inventory decisions and are trained to identify early warning signs in drive behavior, they help reduce abrupt, catastrophic failures that demand emergency parts. Empowered teams can also participate in continuous improvement, fineŌĆætuning reorder points and responding quickly when leadŌĆætime signals change.

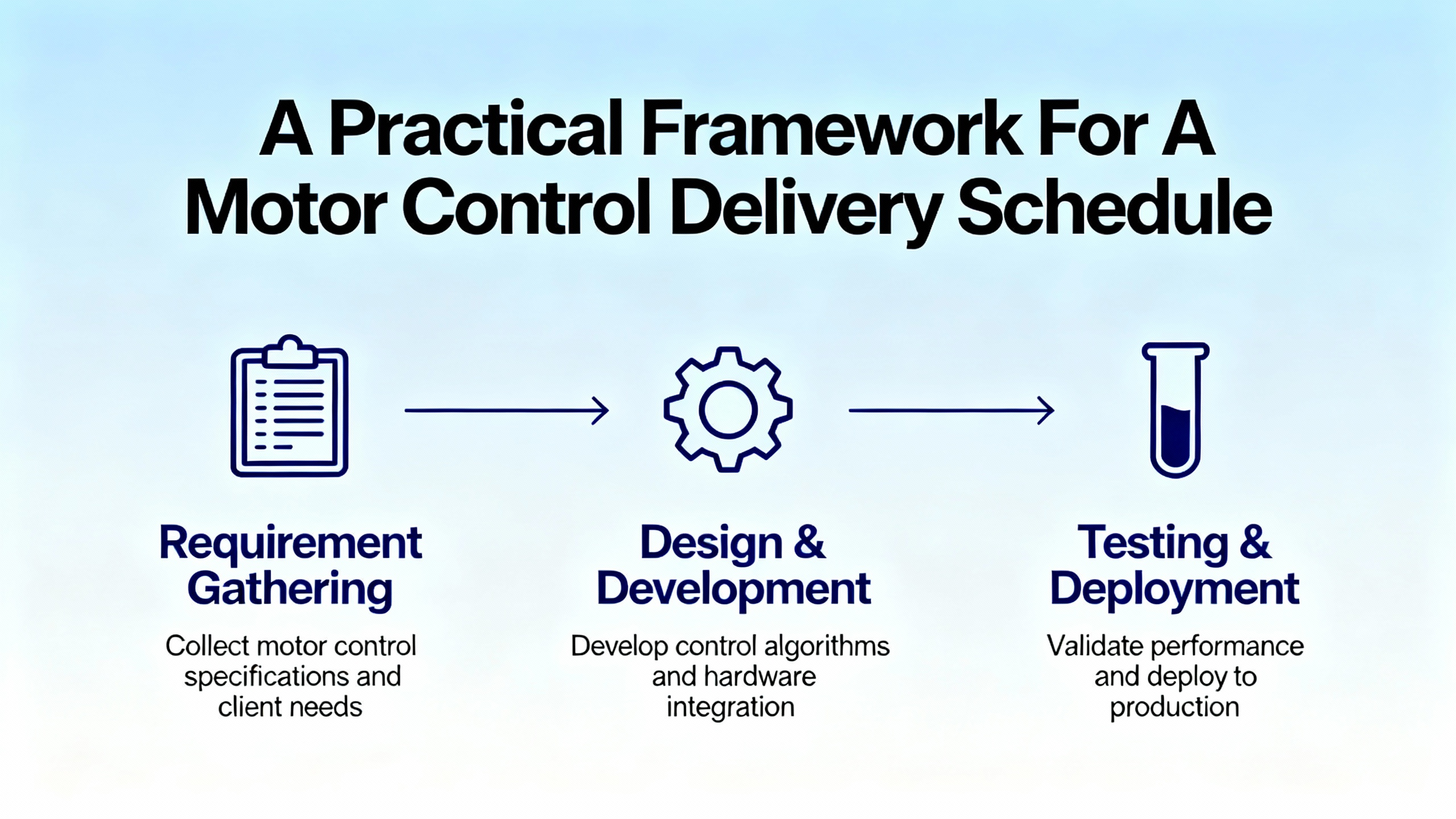

Turning these principles into a concrete motor control delivery schedule for Siemens drive parts requires a structured but pragmatic approach. Production and scheduling experts such as Katana, Epicflow, Tractian, PlanetTogether, and MachineMetrics outline similar multiŌĆæstage processes for manufacturing. Those same stages adapt well to powerŌĆæsystems spareŌĆæparts planning.

The first step is demand forecasting and capacity understanding, but in this context, demand is failure and project demand for drive parts. Use historical work orders, asset ages, environmental conditions, and upcoming projects to estimate what parts you are likely to need over the coming year or two. Katana and CAI emphasize drawing on historical data, regulatory context, and market trends to forecast demand; you can extend that thinking to your installed base and maintenance strategy.

Next, perform material planning and procurement planning specifically for Siemens drive and motor control parts. Identify the raw materials in your case as the part numbers, firmware packages, and accessory kits that each critical asset depends on. Tractian and CAI both advise close collaboration with suppliers to coordinate delivery schedules, negotiate pricing, and maintain quality standards. Here, you also factor in the leadŌĆætime breakdown you have negotiated, so that purchase orders are placed early enough to cover maintenance windows and plausible failure scenarios.

Scheduling and resource allocation then become about aligning maintenance and capital projects with the leadŌĆætime realities of drive parts. Epicflow and MachineMetrics discuss forward and backward scheduling, finite capacity scheduling, and master production schedules. For drives, you can treat major outages and retrofit programs as ŌĆ£production ordersŌĆØ and apply backward scheduling from the desired completion date, inserting lead times for each critical part and resource. That prevents discovering, two weeks before a shutdown, that a key Siemens component has an eightŌĆæweek cumulative lead time.

Production control and monitoring in this analogy corresponds to executing maintenance and project work while tracking actual lead times, deliveries, and installation progress. TractianŌĆÖs concept of PPC emphasizes monitoring and correcting deviations. If a drive part shipment is delayed, your system should immediately show which future work it endangers, so you can resequence tasks, request substitutes, or adjust operating modes.

Finally, you maintain a master schedule of motor control deliveries and associated maintenance activities. MRPeasy and Manufacturing Tomorrow describe how master production schedules act as a contract between sales and manufacturing. In your environment, the schedule ties procurement, maintenance, and operations together. It states which Siemens drive parts will arrive when, which work will be done in the corresponding windows, and how that aligns with risk and production commitments. Regular reviews keep this schedule aligned with reality as lead times, workloads, and priorities change.

The research points to a range of strategies organizations use to manage lead time. Each carries strengths and weaknesses when applied to Siemens drive and motor control components. The table below summarizes typical tradeoffs, drawing on themes from Investopedia, CAI, Umano, LearnAboutLogistics, and Mathison.

| Strategy | Advantages | Limitations / Risks | Best suited for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep local stock of critical drive and UPS parts | Minimizes downtime risk; largely independent of external leadŌĆætime variability; supports rapid repairs and unplanned outages | Ties up working capital; risk of obsolescence; requires strong inventory management | HighestŌĆæcriticality assets where outages are extremely costly |

| Lean stock with emergency expediting | Lower dayŌĆætoŌĆæday inventory cost; relies on premium freight or rush orders only when needed | Vulnerable to systemic transport or capacity disruptions; expediting costs can spike; not effective when upstream production lead times are long | LowerŌĆæcriticality assets or cases where OEM lead times are short and stable |

| Blanket orders and supplierŌĆæheld stock | Balances cost and availability; suppliers can plan production efficiently; can lock in pricing and capacity | Requires trustworthy partners and clear contracts; less flexible if demand pattern shifts sharply | Common replacement parts with predictable demand across your fleet |

| VendorŌĆæmanaged inventory for drive parts | Reduces your planning workload; leverages supplier forecasting and inventory optimization; can improve service levels | Less direct control over stock levels and location; success depends on data quality and collaboration | Facilities with mature relationships and integrated systems with Siemens or distributors |

| MultiŌĆæsourcing and regional hubs | Shorter transit times; more resilience to disruptions in any one lane or factory; potential competitive pricing | More complex supplier management; qualification and interoperability risks for nonŌĆæidentical parts; may not be viable for highly proprietary items | Components with multiple compatible suppliers or modular subsystems |

None of these strategies is inherently right or wrong. The key is to choose deliberately based on leadŌĆætime characteristics, criticality, and your risk appetite, then formalize that choice in your motor control delivery schedule and supplier agreements.

The research underscores that you should work backward from your maintenance windows and worstŌĆæcase leadŌĆætime scenarios, not from average lead times. Once you have a breakdown of cumulative lead time into material, production, and transport, add a reasonable buffer for variability, as recommended by LearnAboutLogistics and Logistics Bureau. For multiŌĆæweek or multiŌĆæmonth cumulative lead times, that often means planning major outages and retrofit campaigns at least one planning cycle ahead, rather than relying on lastŌĆæminute orders.

JustŌĆæinŌĆætime and lean approaches can reduce waste and inventory when lead times are short and stable and when suppliers are reliable, as Umano and CAI describe. However, LearnAboutLogistics warns that variable and long lead times undermine justŌĆæinŌĆætime reliability. For critical Siemens drive and UPS parts with high impact on uptime, it is generally safer to apply lean tools to your internal processes and nonŌĆæcritical items while deliberately carrying safety stock or time buffers for the most critical and vulnerable parts.

MES and productionŌĆæplanning systems such as those described by Plex, Tractian, PlanetTogether, MRPeasy, and MachineMetrics help by providing realŌĆætime data on capacity, inventory, and work status, along with advanced scheduling and whatŌĆæif capabilities. In a power systems context, integrating your CMMS or EAM system with such tools lets you align maintenance planning with spareŌĆæparts lead times, automatically generate purchase orders at the right time, and quickly quantify the impact of any delay on future outages or production.

In industrial and commercial power systems, reliability is no longer just a function of hardware robustness; it is equally a function of how well you understand and manage lead time for the parts that keep that hardware running. When you treat Siemens drive and motor control lead times as measurable, improvable processes, grounded in the kind of practices and data described by CAI, Umano, Investopedia, and others, your ŌĆ£motor control delivery scheduleŌĆØ becomes a genuine reliability tool rather than a hopeful guess. That shift, more than any single spare on the shelf, is what keeps your power protection systems ready when the plant needs them most.

Leave Your Comment