-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

As facilities push for higher availability, tighter power quality, and better cybersecurity, many are discovering a quiet but serious vulnerability in their electrical rooms: aging Schneider PLCs and related software approaching end of life. I routinely walk into plants where a 15–20ŌĆæyearŌĆæold Modicon or building controller still orchestrates automatic transfer schemes, UPS coordination, and generator start sequences. The hardware looks fine, but the OEM has stopped shipping new units, firmware is frozen, and only one technician on staff still remembers the programming tools.

When Schneider Electric publishes an endŌĆæofŌĆælife notice or stops supporting the software stack behind those PLCs, the risk profile of your power system changes overnight. This article unpacks what Schneider’s lifecycle and EOL policies actually mean in practice, why the stakes are especially high for industrial and commercial power systems, and how to plan a practical, lowŌĆærisk migration using Schneider and partner solutions.

Although Schneider’s published lifecycle documents are written for software and GIS platforms, they clearly show how the company approaches support over time for any automation product family, PLCs included. Understanding that framework is the first step toward making sound decisions about your installed base.

Schneider’s End of Life Policy for software and firmware explains that versioning typically follows an X.Y.Z pattern, where X is the platform version, Y is the major version, and Z is the minor version. Two milestones matter most operationally. End of Version is the date Schneider stops licensing a specific version while still selling newer ones. End of Life is the date Schneider ceases maintenance, installation help, and other support for that version. Existing patches usually remain downloadable for a “reasonable period,” but no new fixes are created after EOL.

The ArcFM Product Life Cycle Support Policy illustrates how Schneider structure these phases. Products move through General Availability, Extended Support, Mature Support, then Retired. During General Availability, support is full: businessŌĆæhours phone help, 24/7 online case logging, regular service packs every roughly 6–9 months for certain versions, and certification of new operating systems and databases. Extended Support retains phone and online support, plus patches when warranted, but Schneider no longer certifies new environments. In the Mature Support phase, customers can still call and log cases, but no new patches or environment testing are provided, and this phase typically lasts about a year to give time to migrate. Once a version is Retired, Schneider no longer provides technical support, patches, or any testing in new environments, although your right to use the software itself is unaffected.

Schneider’s broader End of Life Policy stresses that the company reserves the right to handle each product line independently and can change timelines or make custom arrangements. As general guidance, Schneider aims to support the current platform or major version and the previous two major versions, and to give around 90 days’ notice before an End of Version date. Some product families, such as ArcFM Web, have moved to a calendarŌĆæbased policy where each release is assigned a retirement date five years after launch.

From a PLC owner’s perspective, these documents tell you that life cycle is not binary. There is a long middle period where a “mature” platform is still supported but no longer evolving, followed by a clear point where support ceases. Once your PLC family and its associated tools move into those late phases, you are effectively on borrowed time.

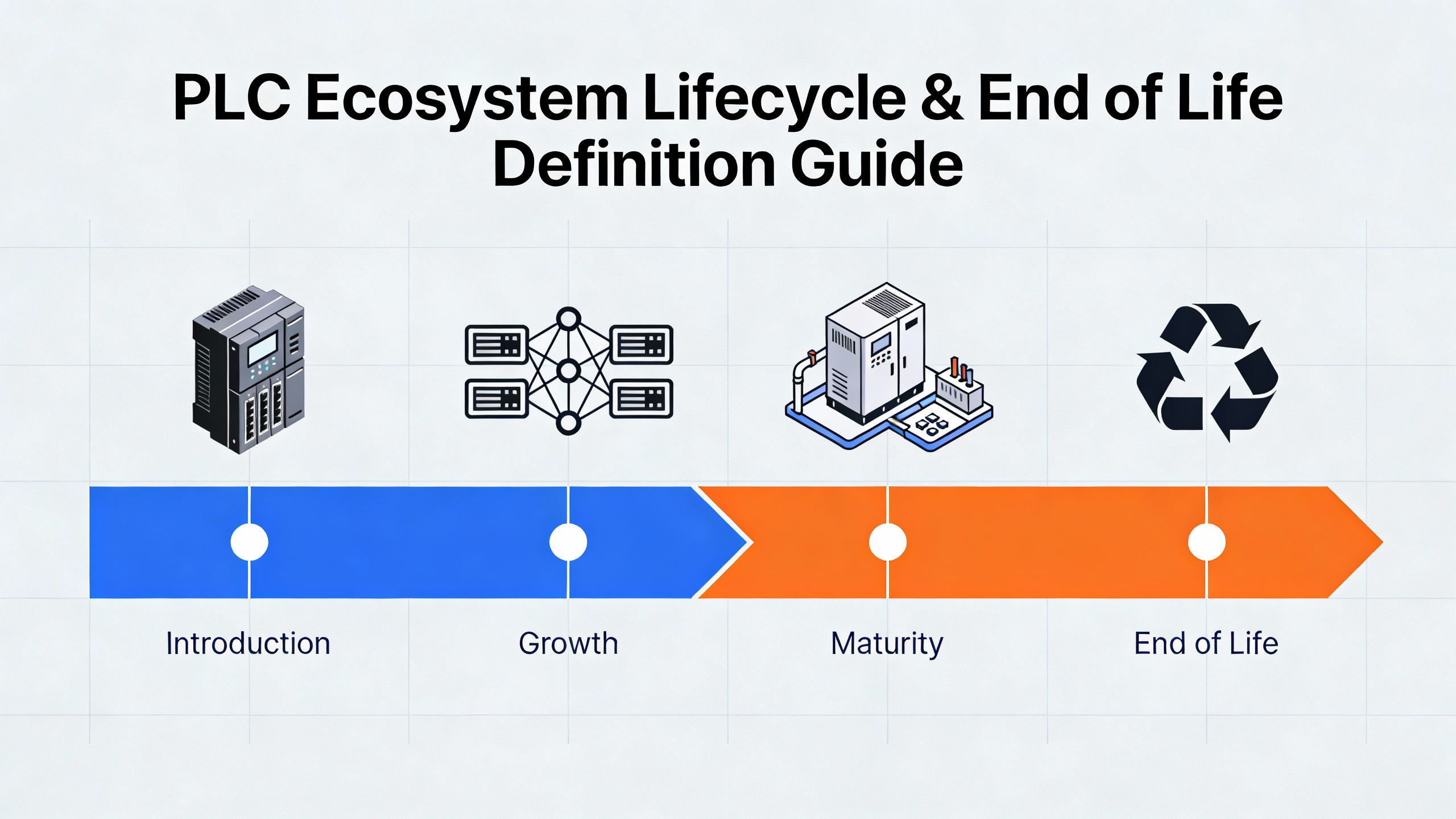

Vendors tend to use precise terms like “end of sale,” “extended support,” or “retired.” Plant staff use a simpler label: legacy. Industry guidance on legacy PLCs describes a life cycle that starts in active production with full support, shifts into mature support with limited updates, passes through endŌĆæofŌĆælife where production has stopped and support is winding down, and ends in an obsolete stage where only secondary markets and thirdŌĆæparty repair remain.

Practical indicators that your Schneider PLC or controller ecosystem is now legacy include a discontinued product series, a lack of firmware or programmingŌĆætool updates, growing difficulty finding technicians who know the platform, and spares that are either scarce or two to three times their original price. Articles on legacy PLCs report that many plants continue running such controllers for 10–20 years past their nominal life, and some anecdotal cases exceed 30 years, especially in clean, temperatureŌĆæcontrolled environments. However, these same sources emphasize that risk and cost of surprises climb every year after OEM support tails off.

Schneider’s own policies reinforce that message. Once a product family is in Mature Support or Retired status, you are unlikely to see new patches, cyber hardening, or testing on the latest Windows Server or SQL version. In other words, the longer you stretch a legacy PLC platform, the more its risk profile diverges from that of your newer UPS, power monitoring, and IT systems.

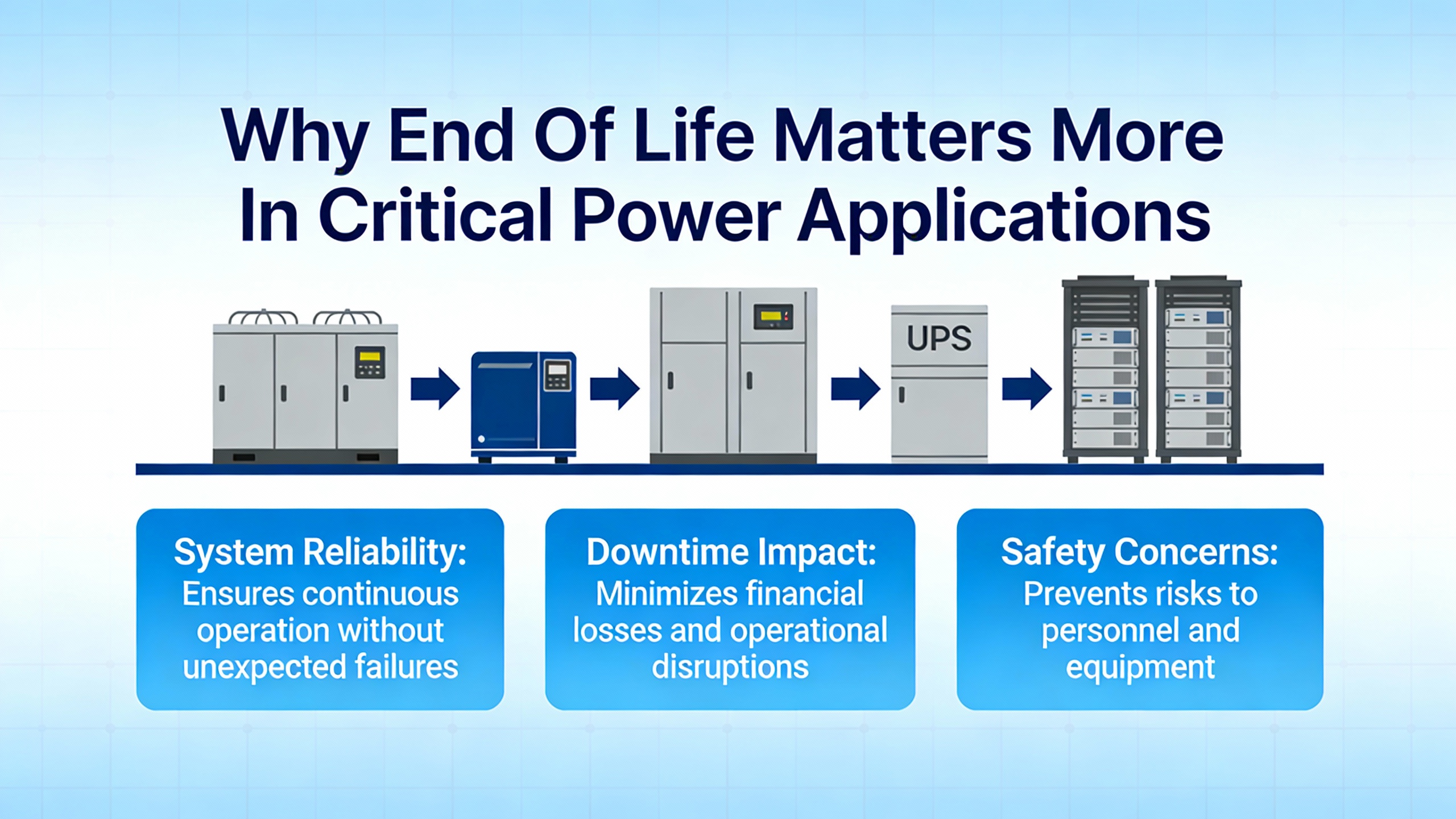

In a generic production line, the cost of a legacy PLC failure is measured in throughput and scrap. In a critical power system—data center, hospital, or semiconductor fab—the same failure can knock out transfer schemes, prevent generators from starting, or leave UPS systems isolated, turning a routine power event into a prolonged outage.

Analyses of legacy PLCs highlight several recurring risks. Parts scarcity is one of the most immediate; controllers, power supplies, and I/O cards for obsolete families can take weeks to source. One published example uses a downtime cost of $10,000 per hour. A fiveŌĆæday wait for a rare replacement CPU at that rate would cost roughly $1.2 million in lost production, not counting penalties or reputational damage. Many facilities easily exceed that hourly rate, especially in lifeŌĆæscience or highŌĆætech environments.

Maintenance providers that specialize in Schneider and APC UPS systems point to similar economics. Schneider’s own survey of data center professionals found that UPSŌĆærelated failures were dominated by battery issues, overloaded capacity, and equipment faults. They also cite broader statistics: U.S. companies can lose on the order of tens of billions of dollars per year to electrical interruptions, and even small businesses may see revenue and productivity losses of at least $1,000 per hour during an outage. When the PLC coordinating your switchgear or UPS bypass path is unsupported and difficult to replace, it becomes part of that exposure.

Cybersecurity adds another dimension. A recent CISA advisory on Schneider EcoStruxure Power Monitoring Expert and Power Operation software described a crossŌĆæsite scripting vulnerability affecting multiple versions. Some affected modules, such as an Advanced Reporting and Dashboards product based on Power SCADA Operation 2020, were already in endŌĆæofŌĆælife support status, with migration to newer offerings recommended. The advisory is clear that older, unsupported versions will not receive the same longŌĆæterm mitigation as current products. Running EOL supervisory software that interacts with your PLCs and power meters increases your attack surface at the very time when ransomware operators are targeting industrial systems more aggressively.

Finally, there is the human factor. As legacy PLC platforms age out of the mainstream, fewer technicians are fluent in their programming environments. Articles on PLC lifespan and modernization note that standardizing hardware and programming practices simplifies maintenance and training, while hanging onto a niche legacy platform often means one or two senior engineers effectively become a single point of failure.

If you connect these threads—parts scarcity, escalating downtime costs, cyber exposure, and skills erosion—the conclusion is straightforward. Extending the life of Schneider PLCs beyond EOL can be reasonable where loads are nonŌĆæcritical and spares are abundant, but in critical power applications, it quickly becomes a gamble that is hard to justify.

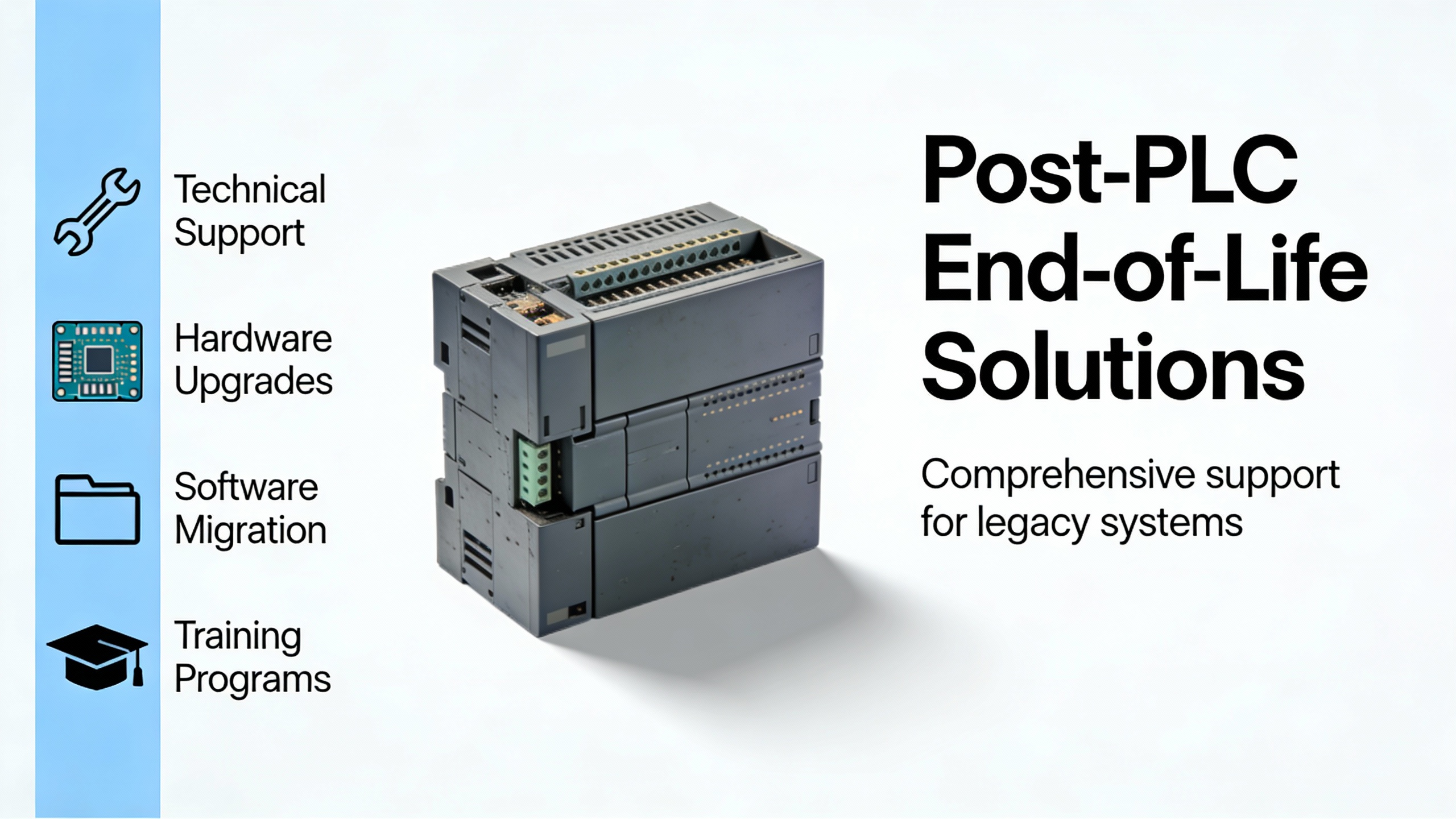

End of life does not mean “you are on your own tomorrow.” Schneider’s lifecycle and service portfolios are designed to create a runway from legacy to modern platforms, particularly where control systems underpin power reliability.

Schneider’s GIS lifecycle policy demonstrates that the company often synchronizes its support phases with upstream platforms. For ArcFM products, support changes track Esri’s ArcGIS versions, and for some desktop and server releases Esri has granted extended Mature Support to March 2028 for utility customers. That kind of alignment is common in Schneider’s automation ecosystem as well; they recognize that utilities and large industrials cannot pivot overnight. The End of Life Policy also notes that custom support contracts can be negotiated on a caseŌĆæbyŌĆæcase basis, which is often how critical infrastructure operators keep a legacy platform supported while they prepare a replacement.

For traditional PLC hardware, Schneider’s PLC Modernization Services provide a defined migration path. These services focus on moving legacy installations—specifically Quantum and Premium PLC platforms—onto the Modicon M580 programmable automation controller, which Schneider describes as an EthernetŌĆæcentric “ePAC.” The goal is not just a new CPU, but a stronger architecture with better visibility and tighter integration into the EcoStruxure ecosystem.

Two key tools underpin this offering. A Unity M580 application converter transforms existing Unity software applications running on Quantum and Premium into equivalent M580 applications. A migration expert configuration utility examines the current installation, identifies gaps, and produces a set of recommendations and preŌĆæengineering data for a new M580 configuration. Together, they shift a large slice of the risk from onŌĆæsite rewiring to preŌĆæproject analysis and software conversion.

One noteworthy feature for highŌĆæavailability environments is the quick wiring system Schneider offers for certain TSX Premium configurations. By using adaptable base plates and wiring adapters, some upgrades can be completed in less than one hour. In practical terms, this means you can upgrade the brain of a switchboard controller or generator sequencing PLC within a single planned outage window, without ripping out and reŌĆæterminating field wiring. Efficiencies gained from the M580 architecture—such as native Ethernet, improved diagnostics, and better integration with plantŌĆæwide software—then combine with that lowŌĆærisk cutover to improve both uptime and maintainability.

These modernization services sit within Schneider’s broader PLC Lifecycle Management Services, complemented by Customer FIRST and Advantage Service Plans on the support side. In other words, Schneider is not only selling you a new PLC; it is offering a structured path from your current risk profile to a supported, sustainable control architecture.

Many power systems use a mix of controllers from different OEMs, and Schneider has positioned its platforms as destinations for those legacy systems as well. One detailed example focuses on Rockwell SLC 500 systems. Analysts estimate tens of billions of dollars’ worth of automation assets worldwide are at or near end of life, with SLC 500 controllers prominent among them.

The proposed migration path in that case is to move from SLC 500 to a UnityŌĆæbased Modicon platform, such as M340, using a twoŌĆæstep approach. SchneiderŌĆædeveloped tools convert existing SLC applications—including tag names and rung comments—into Unity format, preserving the original logic and documentation wherever possible. Unity Pro (now EcoStruxure Control Expert) supports multiple IEC 61131ŌĆæ3 languages, intuitive diagnostics, and preŌĆætested function blocks, so engineers coming from SLC ladder logic can transition without reinventing every routine.

On the hardware side, quickŌĆæwiring terminal blocks bridge from existing SLC field wiring into new Modicon I/O, eliminating the need to pull and reŌĆæland hundreds of conductors. Three migration strategies are commonly referenced: full migration of PLC and extended I/O racks, partial migration where a Unity controller drives existing SLC I/O, or simple CPU replacement while keeping supervisory network connections intact. In a power system, that flexibility lets you stage upgrades around outage windows and critical loads instead of facing a disruptive, allŌĆæorŌĆænothing change.

Once migrated, these controllers can be folded into Schneider’s PlantStruxure architecture, which unifies telemetry, PLC/SCADA, and DCS layers. For a facility manager, that means the same control backbone can handle everything from feeder protection logic to cooling plant optimization and energy reporting, reducing the number of isolated islands to maintain.

Beyond Schneider’s own teams, regional integrators and distributors play a major role in legacy control migrations. Profiles of firms like Guillevin Automation describe a modernization approach that starts with a site audit of devices, networks, and dependencies, followed by offŌĆæsite program conversion and testing, and then either staged migration or a carefully managed ripŌĆæandŌĆæreplace. These integrators often combine Schneider controllers with Weidmüller migration hardware, using preŌĆæengineered marshalling cables and racks to bridge old terminal blocks to new PLCs without disturbing field wiring.

Parallel to modernization, Schneider’s EcoStruxure Service Plans and conditionŌĆæbased maintenance offerings focus on the power equipment itself. For lowŌĆæ and mediumŌĆævoltage gear, Schneider indicates that moving from calendarŌĆæbased maintenance to conditionŌĆæbased programs can extend the time between manufacturer maintenance activities by as much as two years—from roughly three years to about five years—while also targeting root causes of electrical failure. They emphasize that such percentages are nonŌĆæcontractual and based on field experience rather than guarantees, but the pattern is clear: more data and better analytics can both reduce risk and optimize maintenance intervals.

Pulling these threads together, a facility can use Schneider and partner services to modernize PLCs while also adopting smarter maintenance for switchgear, UPS systems, and power distribution, rather than treating controls and hardware as separate lifecycles.

Once you accept that a PLC platform is at or beyond EOL, the next question is not “if” but “how.” Industry experience, including SchneiderŌĆæfocused case studies, generally frames the choice as a spectrum between repairŌĆæandŌĆæhold and full modernization, with several hybrid options in between.

In lowerŌĆæcriticality areas, repair and limited life extension are often the first choice. As long as spare inventory is predictable and the mean time between failures remains stable, keeping a legacy PLC running can be costŌĆæeffective, especially when management needs a threeŌĆæ to fiveŌĆæyear bridge while capital projects are approved. ThirdŌĆæparty repair services and used parts vendors can play a role here, but only if you proactively stage spares rather than hoping the market will deliver when a CPU fails.

As failure frequency increases, or as the PLC’s role in the power system grows more central, replacement quickly becomes the more rational path. Articles on legacy PLC decisionŌĆæmaking recommend building a repair/replace matrix that tags controllers by criticality and observed failure history, then defining triggers—such as two critical failures in 12 months—for moving a given asset from repairable to replaceable. In a power distribution context, a feeder automation PLC with a clean failure record might stay in the repair column for several years, while the controller orchestrating main switchgear interlocks and generator synchronization belongs on an accelerated modernization path.

Three modernization patterns appear consistently in SchneiderŌĆæcentric projects.

One is a quick changeover upgrade, where tools like Schneider’s quick wiring system allow a Premium or Quantum PLC to be replaced by an M580 in the same panel within a very short outage. This is well suited to packaged supervisory control in transfer switches, static transfer systems, or small switchboards.

A second pattern is stepwise or parallel migration. Integrators use industrial gateways to translate between old serialŌĆæbased networks and newer Ethernet platforms, allowing new Schneider PACs to run alongside legacy controllers. Over time, I/O is moved to the new system loop by loop, or subsystem by subsystem, while the old PLC remains as a safety net. Weidmüller’s inŌĆærack or bridge solutions, which mount new controllers over existing wiring arms or route to separate panels via marshalling cables, support this kind of incremental conversion. This approach is ideal for 24/7 plants and hospitals where outage windows are tightly constrained.

The third pattern is a full ripŌĆæandŌĆæreplace. Here, legacy panels are gutted, field wiring is reŌĆæterminated, and a new Schneider architecture—often centered on Modicon PACs, Foxboro DCS, or Triconex safety systems—is installed in one major project. This offers the cleanest end state and the most flexibility in redesign but carries the highest upfront disruption and requires extensive offline testing to avoid surprise behavior at startup.

The right choice depends on process criticality, available shutdown time, the quality of existing documentation, and the balance between capital and operating budgets. What matters most is that the strategy be deliberate and rooted in real risk and cost data, not driven by panic after the first unplanned failure.

To summarize these strategies without resorting to lists, it helps to compare them side by side. A quickŌĆæchange upgrade suits tightly constrained outage windows and relatively simple panels, offering minimal wiring changes but limited architectural redesign. Stepwise migration favors extremely critical facilities that demand reversible, lowŌĆærisk changes at the cost of more hardware and panel space. RipŌĆæandŌĆæreplace becomes attractive when the existing system is poorly documented or fundamentally misaligned with current needs, trading higher project intensity for a clean slate.

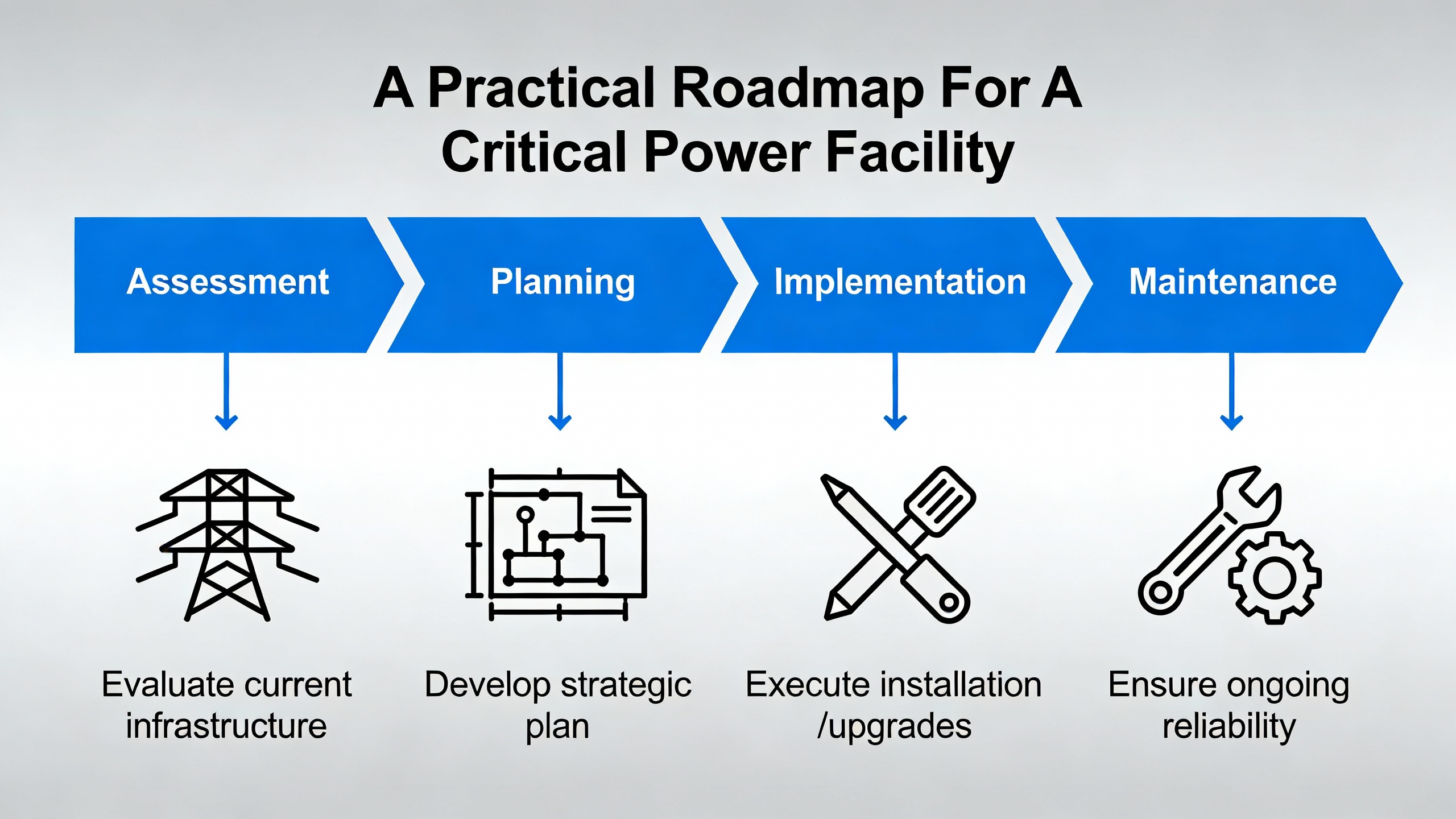

Translating all of this into action, a practical roadmap for Schneider PLC EOL in a powerŌĆæsensitive site usually follows four broad stages: assessment, design, execution, and sustainment.

Assessment begins with an installedŌĆæbase audit. Every Schneider PLC, power monitoring server, and related application should be cataloged with its model, firmware or software version, role in the power system, and lifecycle status. This is where Schneider’s own lifecycle pages and GIS policy tables become invaluable; you can map each software version to General Availability, Extended, Mature, or Retired status and quickly see which elements of your stack are already unsupported. At the same time, you should collect failure history and maintenance records to estimate mean time between failures for each controller.

Design is where you determine your migration strategies controller by controller. For a hospital central utility plant, for example, you might decide that the PLC coordinating generator sequencing and paralleling will move to an M580 via Schneider’s modernization services in the next scheduled maintenance window, using quickŌĆæwiring adapters and preŌĆæconverted Unity applications. Meanwhile, PLCs controlling nonŌĆæcritical support loads, such as parking garage ventilation, might remain on a repairŌĆæandŌĆæhold plan with staged spares and a threeŌĆæ to fiveŌĆæyear replacement horizon. For building automation platforms like Andover Continuum, where public discussion has flagged potential EOL timelines and possible replacement hardware not fully compatible with existing Net Controllers, the design phase should explicitly include a consultation with Schneider to lock down an official transition strategy.

Execution requires disciplined project management. Integrators often set up an offŌĆæsite test bench with representative Schneider hardware and simulated I/O so that converted programs can be verified against the behavior of the legacy PLC before any field cutover. For partial migrations, gateways are installed and exercised while the old PLC remains in charge, ensuring that network and SCADA communications are sound. When outage windows arrive, quickŌĆæwiring systems and preŌĆæengineered adapters become decisive, reducing the risk of wiring errors that are notorious for turning a fourŌĆæhour shutdown into an allŌĆænight recovery effort.

A simple calculation illustrates the payoff. Suppose a modernization project for a key switchboard PLC and supporting software stack costs $600,000 in engineering, hardware, and services. If your downtime cost is $10,000 per hour and the legacy PLC has already caused one 48ŌĆæhour outage over the past few years, that single event represents $480,000 in lost production, not counting reputational or safety impacts. Avoiding just one more incident of that magnitude effectively pays for most of the project.

Sustainment closes the loop by embedding the new system into a broader reliability and maintenance program. ConditionŌĆæbased EcoStruxure Service Plans can be tied to the modernized PLCs and power equipment, enabling remote monitoring, diagnostics, and targeted maintenance instead of fixed schedules. Standardized programming practices across the Schneider fleet, together with upŌĆætoŌĆædate documentation and backups, ensure that future engineers do not face another legacy cliff a decade from now.

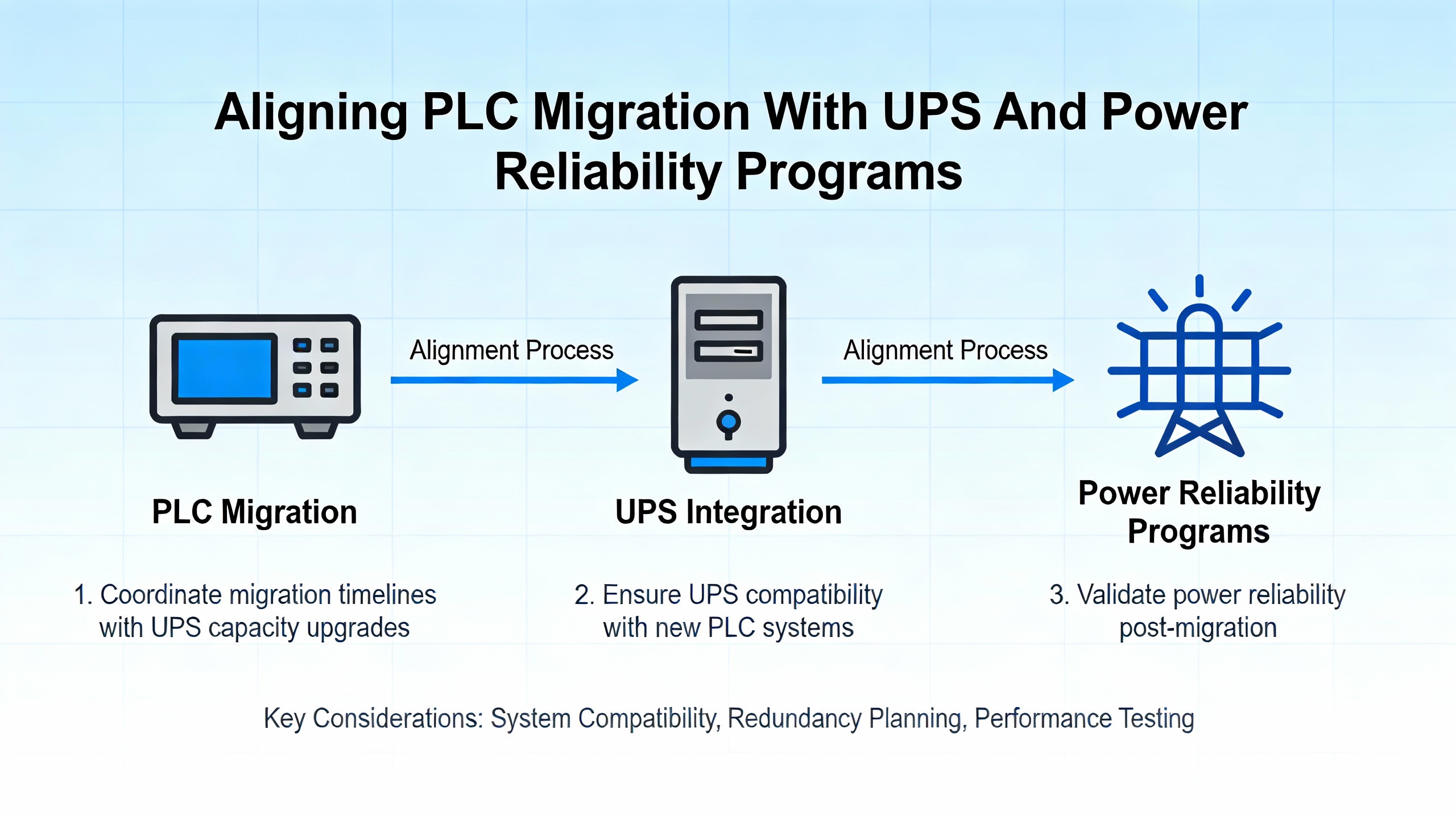

For facilities whose mission depends on clean, continuous power, PLC EOL planning should not occur in a vacuum. It belongs alongside UPS maintenance, switchgear modernization, and broader powerŌĆæsystem reliability engineering.

UPS experts point out that most catastrophic UPS failures are rooted in batteries, capacity issues, or environmental conditions, but that structured preventive maintenance dramatically improves outcomes. Critical power service plans for Schneider and APC UPS fleets typically combine annual or quarterly preventive maintenance with 24/7 corrective coverage and defined onŌĆæsite response times. The point is not just to replace batteries, but to detect and correct weak points before they escalate into failures during a utility disturbance.

The same philosophy applies to PLCs and associated supervisory software. Ensuring your EcoStruxure Power Monitoring Expert and Power Operation installations are on supported, patched versions reduces both cyber risk and the chance of unexpected compatibility issues when operating systems or databases are upgraded. Pairing PLC modernization with an EcoStruxure Service Plan for your lowŌĆæ and mediumŌĆævoltage equipment creates a coherent program where the controls and the power hardware are maintained as one integrated asset, informed by shared data and analytics.

There is a sustainability angle here as well. Schneider’s environmental initiatives emphasize extending product lifecycles, improving efficiency, and providing detailed environmental data for decisionŌĆæmaking. Modern controllers and service plans that reduce unnecessary site visits and avoid catastrophic failures contribute directly to those goals by cutting waste and avoiding energyŌĆæintensive emergency work. While the primary driver for PLC modernization in a power system is uptime, the secondary effects on carbon footprint and resource use are increasingly relevant to corporate boards and regulators alike.

Industry experience with PLC lifespans suggests that controllers can often run reliably for 10–20 years, and in wellŌĆæcontrolled environments sometimes far longer. However, the absence of OEM support and parts becomes more important than the raw age once a product line is in Mature or Retired status. It is generally acceptable to keep running legacy PLCs where loads are nonŌĆæcritical and spare inventory is predictable. Once mean time between failures starts shrinking, spares become hard to source at reasonable cost, or the PLC controls missionŌĆæcritical power equipment, it is prudent to escalate plans toward replacement rather than waiting for a failure to force your hand.

For highŌĆæavailability plants, stepwise or parallel migrations are often safer because they limit the number of changes introduced in any single outage. Schneider and partners offer program conversion tools, wiring adapters, and gateway solutions precisely to support this approach. Each stage can be tested, verified, and, under some schemes, even reversed by reinstalling legacy components without disturbing original field wiring. A full ripŌĆæandŌĆæreplace becomes attractive when the existing system is poorly documented, riddled with workarounds, or fundamentally incompatible with modern requirements, but it should be approached with extensive simulation and testing to avoid surprises at startup.

You should involve Schneider directly when you need official lifecycle status, roadmap information for specific PLC families, or access to formal modernization services such as the M580 migration tools and factory quickŌĆæwiring kits. Schneider is also the primary source for Customer FIRST or Advantage Service Plans and for lifecycle guidance tied to GIS or powerŌĆæmonitoring products. Experienced integrators add value by tailoring those tools to your facility, consolidating multiŌĆævendor equipment into a coherent architecture, and managing the practical realities of outages, documentation gaps, and legacy field wiring. In practice, the most successful migrations in critical power environments use both: Schneider for platform and policy expertise, and trusted integrators for onŌĆætheŌĆæground execution.

In critical power systems, doing nothing about Schneider PLC end of life is itself a decision—with growing risk attached every year. Treat lifecycle notices as early warning, not as an annoyance, and use the combination of Schneider modernization services, conditionŌĆæbased maintenance, and disciplined planning to move your control layer from a legacy liability to a resilient, supportable asset that underwrites your uptime targets instead of threatening them.

Leave Your Comment