-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Keeping industrial and commercial power systems online is ultimately a spareŌĆæparts problem. UPS systems, static transfer switches, generator controls, and power distribution gear all depend on PLCŌĆæclass controllers and related modules. When a CPU, I/O card, or communication module fails, the question is not just ŌĆ£what part fits the slot,ŌĆØ but ŌĆ£what replacement will preserve reliability, safety, and longŌĆæterm support.ŌĆØ

In this guide, I will walk through how to think about Schneider Electric PLC replacement parts and related modules from the perspective of a power system specialist and reliability advisor. The focus is practical: how to identify the right module, avoid compatibility traps, and build a spareŌĆæparts strategy that supports missionŌĆæcritical power infrastructure rather than undermining it.

I will reference guidance and data points from Schneider Electric resources, as well as independent automation and PLC publications, and translate them into powerŌĆæsystem realities such as UPS and power protection environments.

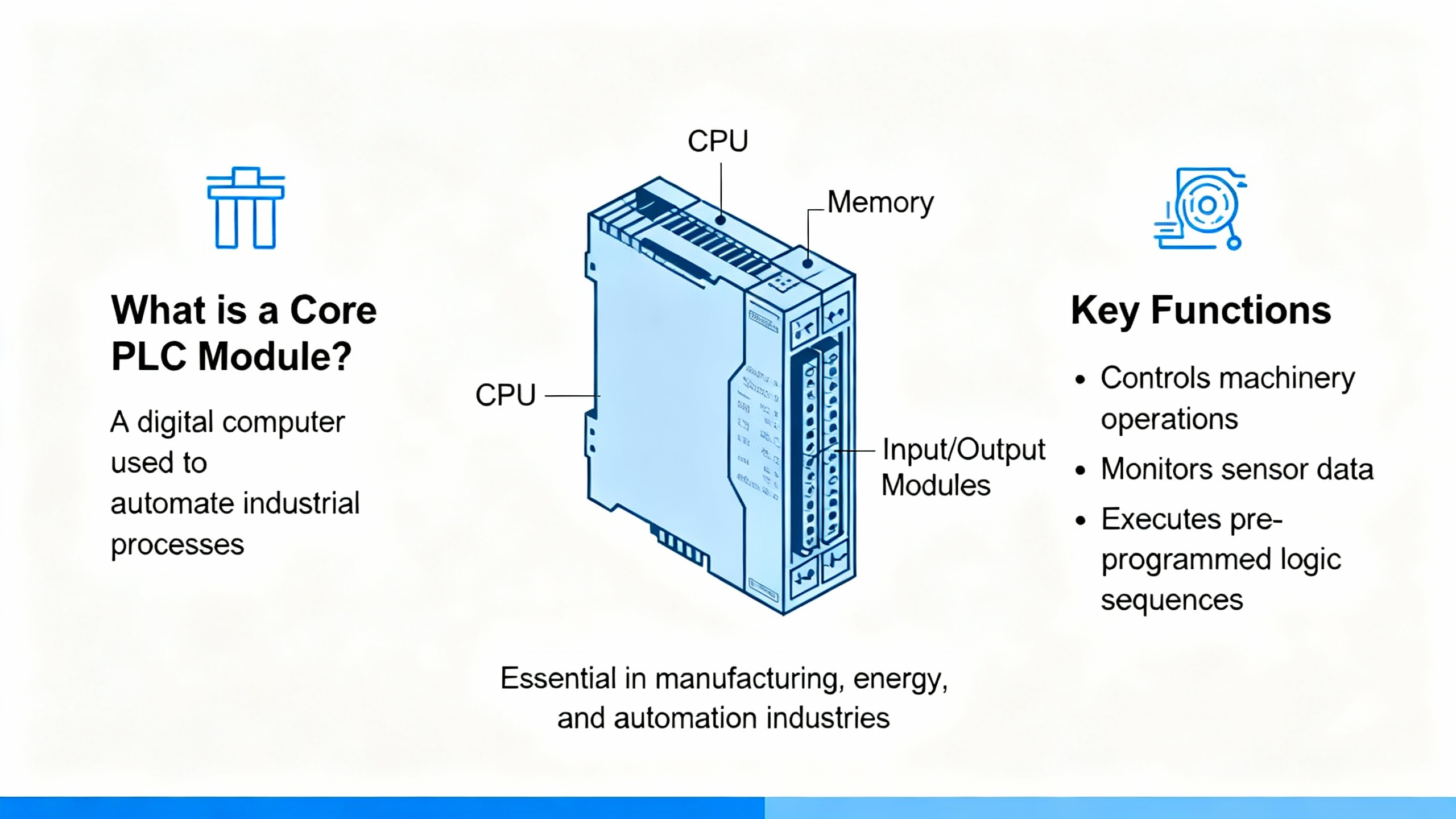

A programmable logic controller is a rugged industrial computer that continuously reads inputs from field devices, executes control logic, and drives outputs to control machinery and processes. Sources such as UpKeep and Empowered Automation describe PLCs as the ŌĆ£brainŌĆØ of automation, sitting between sensors, relays, motor starters, valves, and higherŌĆælevel systems such as SCADA and HMIs.

In critical power applications, that same brain might be supervising automatic transfer switches, coordinating generator start sequences, managing static bypass paths in doubleŌĆæconversion UPS systems, or orchestrating breaker interlocks in lowŌĆævoltage switchgear. Even when the product is branded as a dedicated UPS or switchboard controller rather than a generalŌĆæpurpose PLC, internally it still relies on the same basic architecture: a CPU, power supply, backplane or rack, I/O modules, and communication interfaces.

Pacific Blue Engineering and several PLC training guides emphasize that PLCs are designed to survive vibration, electrical noise, and temperature swings common in industrial environments. That ruggedness is one reason power engineers are comfortable putting PLC modules inside switchgear compartments and UPS cabinets alongside highŌĆæshortŌĆæcircuit currents and transient overvoltages.

When a single module in that chain fails, the risk is not just a loss of convenience but a potential loss of redundancy, loss of automatic transfer capability, or loss of monitoring for overcurrent, ground fault, or battery health. For a data center, hospital, or financial facility, every minute of unplanned downtime can be extremely expensive. Industrial Automation Co. cites industry estimates of about $5,600 per minute for unplanned outages in manufacturing, and powerŌĆæcritical facilities often see similar or higher stakes once contractual penalties and reputational damage are included.

That is why replacement parts for Schneider Electric PLCs and related control modules have to be treated as reliability components, not just catalog items.

Although vendor branding and packaging vary, most Schneider Electric and ModiconŌĆæstyle PLC systems follow the same core architecture outlined by sources such as QIDA Automation, Pacific Blue Engineering, and UpKeep.

The table below maps typical module types to their role in a power system context and to the key replacement considerations.

| Module type | Role in critical power systems | Replacement focus points |

|---|---|---|

| CPU processor module | Executes transfer logic, protection sequences, loadŌĆæshedding schemes | Processing capacity, firmware family, program compatibility |

| Power supply module | Feeds stable DC power to PLC rack and modules | Input voltage, output rating and margin, redundancy, form factor |

| Backplane or rack | Provides data and power bus between all modules | Slot compatibility, data bus speed, mechanical fit |

| Digital I/O modules | Interface to breakers, relays, status contacts, discrete alarms | Voltage and current ratings, isolation level, channel count |

| Analog I/O modules | Interface to CT/VT transducers, temperature, battery sensors | Signal type, resolution, accuracy, isolation, noise immunity |

| HighŌĆæspeed or special I/O | Encoder feedback, synchroŌĆæcheck, fast interlocks where applicable | Supported features, scan performance, wiring compatibility |

| Communication modules | Links to SCADA, BMS, drives, meters via Modbus, Ethernet, etc. | Protocol support, bandwidth, addressing model |

| Safety and protection I/O | Emergency stops, arcŌĆæflash detection, safety interlocks | Safety ratings, response time, certification class |

Publications on PLC architecture highlight a few technical details that matter directly when specifying replacement parts. QIDA Automation notes that modern CPUs can execute control logic with cycle times as fast as 2 nanoseconds and that backplanes can support data rates up to roughly 100 Gbps in advanced systems. For I/O modules, they emphasize that isolation levels commonly fall in the 1,500 to 2,500 volt range, which is very relevant in switchgear and UPS cabinets where control wiring may be exposed to induced transients.

Just as important, QIDA cites a 2024 automation engineering study indicating that roughly 63 percent of system failures traced back to mismatched I/O module specifications, and that about 68 percent of automation failures were tied to incorrect I/O configurations. Although those figures are not SchneiderŌĆæspecific, they underline a key point: in real projects, getting the replacement catalog number right is only half the battle. The underlying electrical and configuration compatibility is often where failures are born.

The CPU is the execution engine. Guides from Pacific Blue Engineering and multiple PLC vendors describe it as the microprocessorŌĆæbased unit that runs the user program, checks diagnostics every scan, and manages communication with I/O and networks.

For replacement, the CPU carries a unique risk profile. Changing only the CPU while keeping the program and the rack can be relatively straightforward if you stay within the same Schneider Electric family and firmware range. However, modernization projects that move from a legacy Modicon or older Schneider controller to a newer platform become controller migration projects, not just spareŌĆæpart swaps.

Balaji Switchgears and Atlas OT, writing about PLC modernization in general, recommend a staged approach. They suggest beginning with an assessment of the existing installation, including a detailed I/O list, network topology, and a full catalog of existing logic, then defining future requirements before picking a target platform. They also point out that automatic program conversion tools are helpful but not infallible, and that rewriting control logic to suit the new controller often yields better reliability and maintainability.

In a powerŌĆæsystem context, replacing a CPU is the moment to revisit loadŌĆæshedding priorities, generator start sequences, and transfer timing, especially if you have experienced nuisance trips or slow transfer events under peak loads.

The PLC power supply tends to be overlooked until it becomes the root cause of a nuisance trip. Power and I/O voltage discussions from Maple Systems and QIDA Automation emphasize that PLC power supplies must be matched to the facilityŌĆÖs standard voltages, commonly 24 to 48 VDC for internal logic and 120 VAC in some cases on I/O.

QIDA reports that about 41 percent of PLC retrofits failed initial testing due to undersized power supplies unable to support the added modules. From a reliability standpoint, that is entirely consistent with what many of us see in the field. When you add just ŌĆ£one moreŌĆØ communication card, plus an extra analog module for a UPS expansion, the original power supply margin quietly disappears.

For Schneider Electric replacement power supply modules, it is not enough to match the catalog family. You need to verify input rating, total load capacity with adequate margin, and derating assumptions for the actual panel temperature and ventilation. In critical power gear where ambient can rise due to transformer or bus losses, that margin is essential.

Backplanes provide both power distribution and highŌĆæspeed communication among modules. While they rarely fail, they are central when you expand or reconfigure.

QIDAŌĆÖs comparison of modular and fixed PLC design notes that modular PLCs provide scalable I/O via chassis slots and often support hotŌĆæswappable components, while fixed PLCs carry a fixed I/O count and usually require full system downtime when any part fails. In industries such as automotive, they report that about 78 percent of plants have adopted modular PLC architectures to support Industry 4.0 demands and faster changeovers, with studies showing up to 40 percent lower upgrade costs compared to fixed systems in some discrete manufacturing environments.

For critical power systems, modular racks give you a path to add additional communication modules, arcŌĆæflash detection I/O, or extra monitoring points without reŌĆæengineering the entire controller. However, when you replace a rack or backplane, you must verify slot addressing, grounding strategy, and mechanical fit, particularly in OEM UPS or switchgear designs where clearances can be tight.

Input and output modules are where abstract PLC logic meets real-world conductors. Sources such as Maple Systems, UpKeep, and QIDA Automation all stress the importance of matching I/O types and ratings to the connected field devices.

Digital input and output modules in power applications typically interface with breaker auxiliary contacts, protective relay outputs, status switches on UPS components, and discrete alarms. They usually operate at 24 VDC or occasionally 120 VAC. QIDA highlights that mismatched electrical ratings, including voltage and current thresholds, account for about 34 percent of automation system failures in general industrial settings.

Analog modules handle signals such as 4ŌĆō20 mA current loops for CT and VT transducers, DC bus voltage sensing, battery temperature, or load percentage outputs from meters. The same QIDA guidance shows that dedicating appropriate analog channels and channel isolation is critical in noisy environments, with case studies where proper use of highŌĆæspeed counters for encoders reduced timing errors by over 40 percent compared with shared configurations.

For replacement, that means you must confirm each of the following for every Schneider Electric I/O module you substitute: signal type and range, channel count, isolation level, and whether any integrated filtering or scaling is handled by the module or by the PLC program. Any discrepancy can silently corrupt measurements or control outputs long before you notice a complete failure.

Modern power systems ride on communication as much as on copper and steel. Articles on discontinued drive replacement and PLC modernization emphasize the importance of matching communication protocols when replacing components. Typical plant networks mix Modbus RTU or Modbus TCP, EtherNet/IP, PROFINET, older DeviceNet or PROFIBUS, and increasingly OPC UA.

QIDA notes that many plants still run legacy protocols alongside newer IIoTŌĆæready networks, and that dualŌĆæprotocol or protocolŌĆæagnostic modules can reduce integration time by around 40 percent compared with proprietary ecosystems. For Schneider Electric installations, communication modules often provide the bridge between PLC logic and EcoStruxure systems, thirdŌĆæparty BMS platforms, or drive and meter networks.

Replacing these modules requires checking not only the physical interface but also whether the specific option supports all the protocols you rely on. For example, an Ethernet module that handles Modbus TCP may not support another vendorŌĆÖs preferred protocol used elsewhere in the plant. When your UPS status, breaker positions, and generator alarms all flow through that bridge, you cannot afford guesswork.

Schneider Electric offers several online tools that can simplify the first steps in identifying replacement parts, but they must be used with the right expectations.

A Schneider Electric product crossŌĆæreference application provides suggestions for products that may serve as replacements or equivalents for other Schneider or nonŌĆæSchneider devices. The legal notice for this tool states explicitly that the information is proprietary, confidential, and provided strictly ŌĆ£as is.ŌĆØ It also emphasizes that functionally equivalent products suggested by the tool are not guaranteed to be fully equivalent in form, fit, and function, and that physical, performance, or interface differences may exist.

The same notice makes two key points that matter for reliability engineering. First, Schneider Electric disclaims all warranties, including implied warranties of merchantability and fitness, regarding the crossŌĆæreference information. Second, they explicitly instruct users to independently verify whether any suggested replacement is appropriate for their specific application and to review product literature and documentation to confirm characteristics before adoption.

Separately, Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs online Product Selector tool is positioned as a guided questionŌĆæbased interface that helps users identify products and compatible accessories. It supports lookups based on catalog reference and allows configuration of options to return matching suggestions. The tool is designed as a selfŌĆæservice aid, accessible without login, to accelerate product and accessory selection.

Using these tools together with careful engineering review is often the most efficient approach. In practice, a good workflow for a Schneider PLC module replacement looks like this. First, collect the exact part number, module type, firmware where applicable, and detailed application context from the existing system. Next, use the Product Selector or crossŌĆæreference tool to identify candidate replacements or successors. Then, retrieve data sheets, wiring diagrams, and application notes and compare electrical ratings, isolation, backplane compatibility, communication protocols, and mechanical details. Finally, validate the choice against your plant standards, safety requirements, and network topology, and benchŌĆætest when possible before field installation.

The critical point is that SchneiderŌĆÖs own documentation treats these tools as aids to engineering judgment, not substitutes for it. For critical power systems, that distinction is essential.

Not every failed module needs to become a modernization project. Industrial Automation Co. frames the repairŌĆæversusŌĆæreplace decision in terms of downtime cost, criticality, and the economics of tariffs and lead times.

They point out that unplanned downtime for manufacturers can run around $5,600 per minute and that in 2025 tariffs on foreignŌĆæmade automation parts in some categories increased prices by roughly 30 to 145 percent. They also note OEM lead times of 10 to 16 weeks even for common modules. In this environment, repair and highŌĆæquality refurbished modules have become more attractive in many cases.

Their guidance, which translates well into the PLC and powerŌĆæsystems world, suggests that repair is usually sensible when the part is nonŌĆæcritical, the failure appears isolated (for example, a damaged board or capacitor), direct replacements are hard to source, and you have a trusted repair partner who performs full functional testing under load and offers a multiŌĆæmonth warranty. Replacement is recommended when the part is missionŌĆæcritical and already causing severe downtime costs, has failed multiple times despite previous repairs, or when repair price exceeds about half of the cost of a new or surplus unit. Obsolescence and lack of modern communication or diagnostics are also strong arguments in favor of replacement and modernization.

Balaji Switchgears and Atlas OT, writing about broader PLC upgrades, emphasize migration strategies such as phased upgrades, parallel running of old and new controllers, and full replacements during planned shutdowns. They underscore that controller replacement is an opportunity to improve diagnostics, cybersecurity, and scalability rather than just swapping hardware.

In a UPS and power protection environment, the stakes guide the choice. A failed communication module that only feeds a noncritical monitoring screen might reasonably be repaired or replaced with a refurbished unit to avoid long lead times. In contrast, a CPU module running generator paralleling logic for a hospital microgrid, or a safetyŌĆærated I/O module handling emergency shutdown signals, is a strong candidate for outright replacement with a current, supported model, even if repair appears less expensive on paper. The potential downtime and safety implications dominate.

Several sources highlight how often compatibility oversights cause failures in PLC projects. QIDA Automation reports that mismatched electrical specifications account for about 34 percent of automation failures, and that ensuring voltage ratings, current thresholds, and form factors align with the application is essential. They also emphasize the importance of ensuring power supply capacity and alignment with module loads, citing that more than 40 percent of retrofits they examined failed early tests because new modules pushed power supplies beyond what they were designed to handle.

For Schneider PLC replacement parts in critical power systems, think about compatibility in three layers.

At the electrical layer, verify voltage and current for each I/O point and the power supply. For example, confirm that digital inputs are designed for the same 24 VDC or 120 VAC level used in your existing wiring and that the output current ratings match the solenoids, coils, or interface relays they drive. Ensure isolation ratings are suitable for the environment; QIDAŌĆÖs figures in the 1,500 to 2,500 volt range for I/O isolation give a sense of what is common for industrial modules, but you must confirm the specific ratings of the Schneider part you intend to use.

At the logical layer, focus on how the module is addressed and configured. Mapping differences in channel order, default scaling for analog modules, or diagnostic bit conventions can break protection schemes or monitoring logic without any obvious wiring errors. Tools like SchneiderŌĆÖs own programming environments and bestŌĆæpractice recommendations from PLC programming experts such as RL Consulting emphasize clear documentation, naming conventions, and separation of normal operating logic from fault handling. When you change a module, updating and reviewing that documentation becomes part of the compatibility check.

At the network layer, confirm protocol and addressing. If the existing PLC talks Modbus TCP to UPS systems and Modbus RTU or PROFIBUS to drives and protection relays, the replacement communication module must support those exact protocols and capacities. Publications on replacement for discontinued drives and strategies for upgrading PLC hardware all stress that network compatibility is often the deciding factor between a ŌĆ£plugŌĆæin replacementŌĆØ and a complete controlŌĆæsystem upgrade.

Schneider Electric positions spareŌĆæparts management as a distinct service area. Their spareŌĆæparts management materials describe EcoStruxure Service Plans as tailored service contracts that combine the EcoStruxure digital platform with remote consultancy and onŌĆæsite and dynamic maintenance. These plans range from essential support to the most advanced expertise and explicitly include conditionŌĆæbased approaches rather than purely reactive or calendarŌĆæbased maintenance.

A complementary perspective comes from PLC AutomationŌĆÖs discussion of critical spare parts. They define critical spares as components whose failure can cause costly downtime, production delays, or unsafe conditions. Examples in their context include motors, drives, control systems, sensors, actuators, power supplies, and circuit boards. Their recommendations include formally identifying which parts are critical by considering the role in the process, replacement difficulty, and procurement lead times; maintaining a visible inventory of critical spares; storing them properly; and using a computerized maintenance management system to track usage and plan reorders.

UpKeepŌĆÖs PLC maintenance guide adds details around preventive maintenance routines for PLC hardware, such as cleaning, inspecting terminals for looseness or discoloration, backing up programs, and checking environmental conditions and diagnostic indicators at least annually.

Bringing these threads together, a robust Schneider Electric PLC spareŌĆæparts strategy for power systems typically includes the following practices, expressed as ongoing disciplines rather than oneŌĆætime tasks. Start by identifying which PLC modules in your UPS, switchgear, generator, and powerŌĆæmonitoring systems are truly critical. Then, for those critical modules, hold at least one tested spare on site whenever lead times or tariffs make rapid replacement uncertain. Use SchneiderŌĆÖs spareŌĆæparts database and Product Selector to confirm that the spareŌĆÖs catalog number, firmware, and configuration options match the installed equipment. Integrate part numbers, locations, and lastŌĆæknown test dates into your maintenance management system. Finally, if your organization lacks the time or expertise to manage those details, consider leveraging Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs EcoStruxure Service Plans to externalize part of the spareŌĆæparts management burden while still insisting on clear visibility into what is stocked and where.

Multiple sources point out that modular PLC designs offer a better path for scaling and upgrading systems over time. QIDAŌĆÖs 2024 guide on choosing PLC modules reports that modular architectures allow engineers to add specific modules such as analog cards or communication gateways without full system replacement, saving in the range of 35 to 50 percent compared with replacing fixed PLC installations when expansions are needed. They also describe design practices such as reserving roughly 25 to 30 percent spare I/O capacity, about 30 to 40 percent additional memory, and around 20 percent powerŌĆæsupply capacity to accommodate future growth.

In automotive plants, QIDA notes that modular architectures have been adopted by about 78 percent of plants, in part because this approach reduces changeover downtime during model changes by approximately 22 percent compared with unitary PLC setups. While those studies focus on manufacturing, the same logic applies to power systems. Expanding a UPS plant, integrating energy storage, or reŌĆæsegmenting switchgear for a new tenant becomes much easier if the original PLC design reserved I/O, communication ports, and rack space for those changes.

For Schneider Electric PLC systems, that means choosing replacement backplanes and CPU families that still have a future roadmap, and favoring modular designs where practical. Premier Automation and other controllerŌĆæselection experts also recommend looking at communication portfolios, Industrial IoT readiness, and software support horizon when choosing a controller family. For power systems, add one more criterion: the expected lifecycle of the switchgear, UPS, or generator compared with the controller lifecycle. If the electrical equipment is expected to operate for decades, you want a PLC platform with a clear longŌĆæterm migration story from the vendor.

Bringing all these elements together, a practical workflow for Schneider Electric PLC module replacement in a critical power environment typically follows a structured pattern similar to what Siemens, Balaji Switchgears, and others describe for controller replacement, adapted here to power applications.

Begin with an installedŌĆæbase assessment at the control level. For the affected UPS, switchboard, or generator control, document all PLC modules by catalog number, slot, and function. Capture the I/O list, including each signalŌĆÖs voltage, type, originating device, and destination. Map communication links and protocols. In parallel, assess the criticality of the function; losing a monitoring display is very different from losing an automatic transfer sequence.

Next, identify the failure and its scope. Determine whether the issue is truly a module failure or an upstream problem such as power quality, bad wiring, or environmental stress. If the module has failed repeatedly, consider whether that points to a design limitation rather than bad luck. This step informs the repairŌĆæversusŌĆæreplace decision described earlier.

Then, select candidate replacements. Use Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs crossŌĆæreference information and Product Selector to identify appropriate replacement or successor modules, noting all disclaimers about ŌĆ£as isŌĆØ information and the need for independent verification. For legacy modules that are fully obsolete, consult Schneider technical support or an experienced system integrator to identify migration paths that minimize wiring and program changes.

After that, verify compatibility in detail. Compare electrical ratings, backplane requirements, isolation levels, and communication capabilities. Review programming impacts, such as configuration data blocks and addressing. If possible, build or simulate the configuration offline and perform bench testing using representative I/O loads. Many PLC bestŌĆæpractice sources, including RL Consulting, emphasize the value of simulation, clear separation of normal and faultŌĆæhandling logic, and structured testing before commissioning.

Finally, plan and execute the field change with a clear cutover and rollback strategy. In power systems this often means scheduling the replacement during a maintenance window, temporarily transferring load to alternate sources or bypass, and having the old module and original configuration ready to reinstall if the new solution misbehaves. Document all changes, update oneŌĆæline diagrams and control drawings, and train operators on any new diagnostics or alarm behaviors introduced by the new module.

This may sound methodical, but in practice it is what keeps seemingly small module replacements from becoming long outages or subtle reliability problems.

Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs crossŌĆæreference information and Product Selector can significantly shorten the time needed to find candidate replacement parts for obsolete or thirdŌĆæparty modules. However, SchneiderŌĆÖs own legal language stresses that these tools are aids only and that suggested replacements are not guaranteed to be fully equivalent in form, fit, and function. In critical power projects, treat the toolŌĆÖs output as a shortlist and then perform detailed technical verification, including dataŌĆæsheet comparisons, wiring checks, and offline testing where practical.

General PLC modernization guidance from sources such as Balaji Switchgears, Atlas OT, and Industrial Automation Co. suggests moving from module replacement to full controller modernization when repeated failures occur, when parts are fully obsolete, when needed communication or diagnostic capabilities do not exist on the current platform, or when the risk and cost of downtime exceed the incremental cost of an upgrade. In critical power systems, if the existing controller cannot support modern networking, remote diagnostics, or safety requirements for the life of the power equipment, modernization becomes a strategic reliability investment rather than a discretionary upgrade.

There is no single formula, but best practices drawn from PLC AutomationŌĆÖs discussion of critical spares and QIDAŌĆÖs capacityŌĆæplanning recommendations support a riskŌĆæbased approach. For components whose failure would immediately compromise automatic transfer, protection, or monitoring of critical loads and that have long lead times or tariffŌĆæinflated costs, hold at least one tested spare on site. For less critical modules, you may rely on SchneiderŌĆÖs supply chain or service plans. The key is to formally identify which modules are critical, document where spares are stored, and keep them maintained and periodically tested rather than simply sitting forgotten on a shelf.

Industrial Automation Co. points out that highŌĆæquality repair and surplus components can be a costŌĆæeffective option, particularly when tariffs and lead times on new parts are high. They emphasize that any repair partner should perform full functional tests under realistic loads and offer a meaningful warranty on workmanship and performance. For missionŌĆæcritical power systems, refurbished or thirdŌĆæparty modules may be appropriate for some roles, especially for nonŌĆæsafety functions or monitoring, but OEMŌĆænew parts and manufacturerŌĆæsupported migration paths usually present lower longŌĆæterm risk for core protection and control functions. The decision should weigh downtime cost, risk tolerance, and the availability of expert testing.

In the end, Schneider Electric PLC modules in your power system are part of the protection chain, not just commodity electronics. Treating replacement parts as engineered reliability componentsŌĆöselected with the help of SchneiderŌĆÖs tools, validated against detailed specifications, and supported by a deliberate spareŌĆæparts strategyŌĆögoes a long way toward keeping your UPS systems, inverters, and power protection equipment quietly doing their job when the rest of the grid is not.

Leave Your Comment