-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When an ABB variable frequency drive trips on fault in the middle of a production run, the pressure is immediate and very real. Motors are stopped, processes are frozen, and phones start ringing. In my work supporting industrial and commercial power systems, I see the same pattern over and over: a fault code appears on the ABB drive keypad, someone acknowledges it without really reading it, and then the panic search begins for a quick way to ŌĆ£reset everything back to normal.ŌĆØ The fastest way back to normal, however, is not blind resetting. It is a structured approach that combines correct fault interpretation, careful parameter verification, and, only when justified, a controlled parameter reset and reconfiguration.

This article walks through that workflow with ABB drives in mind. The focus is on AC drives such as the ACS series and on DC drives such as the DCS800, where parameter sets and resets are particularly important. The goal is to get you from ŌĆ£faulted and stuckŌĆØ back to ŌĆ£running reliablyŌĆØ without creating a bigger problem by erasing or corrupting good configurations.

A variable frequency drive is essentially a computer plus a power converter. It rectifies incoming AC to DC, conditions it on a DC bus, and then uses insulated gate bipolar transistors or similar devices to recreate controlled AC for the motor. The control section constantly monitors voltages, currents, temperatures, and logic states. When an abnormal condition exceeds what the drive considers safe, it generates a fault code and shuts down to protect itself, the motor, and the driven equipment.

On ABB drives, those fault codes are your first diagnostic tool. They are visible on the keypad or HMI for platforms such as the ACS310 and ACS355, and they are also captured in event logs or tools such as ABB Drive Composer on larger frames like the ACS580 and ACS880. Each code points you toward a specific class of problem. For example, common codes reported in ABB troubleshooting guides include overcurrent, overvoltage, undervoltage, overtemperature, motor stall, earth fault, and internal fault. These are not random messages; they are a compressed summary of what the protection logic has seen.

To make this more concrete, consider a few representative examples that appear frequently in ABB documentation and in the field.

| ABB fault code | Meaning in plain language | Typical root causes | First checks and actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| F0001 ŌĆō Overcurrent | The drive output current has spiked above safe limits. | Sudden load increase, mechanical jam, shorted motor cable, or overly aggressive acceleration. | Inspect the driven machine for binding, confirm motor cable integrity, and lengthen acceleration time if it is very short. |

| F0002 ŌĆō Overvoltage | The DC bus voltage has risen higher than allowed. | High incoming line voltage, regenerative load, or aggressive deceleration without adequate braking. | Measure supply voltage, verify braking resistor sizing and wiring, and increase deceleration time. |

| F0003 ŌĆō Undervoltage | The DC bus voltage has dropped below minimum. | Line dips, missing phase, loose input connections, or upstream protection opening. | Check fuses and breakers, verify all input phases, and retorque suspect terminals with power safely off. |

| F0005 ŌĆō Device Overtemperature | Internal components have exceeded their temperature limit. | Dirty or blocked cooling paths, failed fans, or high ambient temperature. | Clean filters and heat sinks, confirm fan operation, and ensure the enclosure has the clearances and cooling specified by ABB. |

| F0010 ŌĆō Motor Stalled | The motor cannot reach commanded speed. | Load too heavy, mechanical jam, incorrect motor data, or undersized drive. | Examine the mechanical load, verify motor nameplate data in parameters, and test the motor windings. |

| F0022 ŌĆō Earth Fault | Current has leaked to ground on the output side. | Damaged cable insulation, contaminated terminal box, or internal motor fault. | Use an insulation tester to check motor and cables, and inspect terminal boxes for moisture and debris. |

| F0023 ŌĆō Internal Fault | An internal control or hardware error has been detected. | Control board failure, firmware issue, or serious internal component problem. | Power cycle the drive once; if the fault persists, escalate to ABB or a qualified drive service center. |

The lesson from this table is that the drive is already doing much of the initial diagnosis for you. Before touching any parameters, you should record the exact fault code, the operating state at the time of the trip, and any repeating pattern. That fault context is crucial when you later decide whether a parameter reset is actually appropriate.

Every ABB drive ships with a factory-default parameter set that tells it how to behave in a generic configuration. To work properly on your system, the drive must be tailored to your motor and application. That tailoring happens in parameters. At a minimum, you enter motor nameplate data such as rated voltage, current, base frequency, and speed. You also configure control mode, acceleration and deceleration times, minimum and maximum speed limits, I/O behavior, fieldbus addresses, and any application-specific features such as PID loops or brake control.

If those parameters are wrong, even a perfectly healthy motor and power system can trip the drive. Typical examples documented in both ABB material and general VFD references include setting a rated current lower than the actual motor current, which leads to overload trips; choosing the wrong control mode or speed limits, which causes poor torque control or unexpected trips; entering wrong motor voltage or frequency, which increases heating and can trigger overcurrent; and misconfiguring digital or analog inputs so that the drive sees conflicting run commands or invalid references.

Parameter problems are especially common after a control board replacement, firmware update, or a poorly documented commissioning effort years earlier. In some cases, operators accidentally trigger a parameter reset and do not realize that custom application logic, fieldbus mappings, and I/O settings were wiped. In others, the drive is a spare pulled from storage with factory defaults still loaded, but it is installed on a system that expects a tuned configuration.

Because of this, I treat parameters as both a valuable asset and a potential liability. They are an asset when you have clean documentation and backups. They become a liability when the only copy of a working configuration lives inside one aging control board.

As tempting as it is to jump straight to a ŌĆ£factory resetŌĆØ when nothing seems to work, that should be one of the last steps in your troubleshooting process, not the first. A structured workflow, grounded in both ABB guidance and general VFD practice, keeps you from erasing useful information or compounding a simple wiring error with a configuration disaster.

Start by making the situation safe. Lock out and tag out the incoming power, and wait for the DC bus capacitors to discharge. Many drives show DC bus voltage on the keypad; alternatively, the manual will specify a wait time. Always verify the absence of dangerous voltage with a meter before touching internal terminals.

Next, document everything. Write down the fault code, note any alarms that preceded it, and record the drive status and speed command at the time of the trip. If your ABB drive supports an event history, capture that log. If there is an existing parameter backup file from ABB Drive Composer or another tool, copy it to a safe location as it is; even a flawed configuration is useful as a reference.

Once you have a snapshot of the fault and configuration, move outwards to the basics. Confirm correct input power, including all phases, voltage level, and frequency. Inspect fuses or breakers and look for signs of overheating at terminals. Verify motor wiring for correct connections and phase sequence, and check the motor mechanically for binding or seized couplings. Many issues that present as ŌĆ£mysterious ABB drive faultsŌĆØ are actually very simple problems such as a loose lug or a mechanically jammed pump.

Only after power and the motor side have been verified should you turn back to parameters. Compare the driveŌĆÖs motor data parameters with the actual nameplate. Check acceleration and deceleration times against the inertia of the driven equipment, and make sure minimum and maximum speeds are reasonable. Confirm that control mode and feedback sources are correct for your application. This kind of review often reveals a clear mismatch without any need to reset the entire drive.

If, after these checks, you find that the parameter set is clearly corrupted, incomplete, or unknown, then it may be time to consider a factory reset followed by a controlled reconfiguration.

The phrase ŌĆ£reset the driveŌĆØ is used loosely in many plants, but there is an important difference between acknowledging a fault, restoring power after a trip, and resetting parameters. Resetting a fault simply clears the error once the underlying condition has been removed. Power cycling the drive removes active faults but does not change parameter values. A factory reset, by contrast, deliberately returns part or all of the parameter set to ABBŌĆÖs default values.

On ABB drives, the details of a factory reset procedure vary by product family. What they have in common is a dedicated system parameter that, when set to a specific value, triggers a reset. For example, on a DCS800 DC drive, ABB documentation describes a process where you place the drive in local control mode, navigate to a system parameter group, and use a particular parameter to request a factory reset. On that platform, the sequence uses parameter group 99 and parameter 99.08. When you assign the value that ABB labels as ŌĆ£FactoryŌĆØ and confirm it, the drive reloads its default parameter set. The key point is not the exact parameter numbers, which are model-specific, but the principle that ABB provides an explicit, deliberate reset mechanism and expects you to use it only when you understand the consequences.

Because a factory reset discards local customizations, I strongly recommend treating it as a controlled maintenance action. Before you trigger it, do everything you can to preserve your current parameter set, even if it is not working perfectly. If your drive is an ACS580 or ACS880 with PC connectivity, export the parameter file via ABBŌĆÖs tools. If that is not possible, at least photograph or manually record the most critical parameters such as motor data, I/O assignments, and fieldbus settings. That rough record can be invaluable later if you discover that a ŌĆ£defaultŌĆØ behavior no longer meets your process needs.

In some cases, a full factory reset is unnecessary. If you have a known-good parameter backup from the same drive or an identical unit, restoring that backup may be safer than wiping everything to defaults. ABB recommends backing up parameter sets and firmware versions as part of normal preventive maintenance precisely so that you have a clean baseline to return to after hardware replacement or corruption.

To illustrate how ABB implements parameter resets, consider the DCS800 DC drive, a platform commonly used in industrial applications where precise torque control is needed. On this family, ABB illustrates a factory reset procedure that relies entirely on the front-panel keypad, with no external software.

The sequence begins by placing the drive in local mode using the LOC/REM button on the keypad. Local mode ensures that the drive responds to commands from the panel, not from a remote controller. Once in local, you press the ENTER key to access the main menu and select the parameter menu. From there you navigate to parameter group 99, which ABB reserves for system and utility parameters that include maintenance and reset functions. Within that group you select parameter 99.08. ABB designates this parameter specifically as the factory reset selector.

To request a reset, you change the value of parameter 99.08 to the value labeled ŌĆ£Factory,ŌĆØ which corresponds to a numeric setting described in the manual, and then confirm the change with ENTER. At that point the drive resets its configuration to factory defaults. After the reset, you must re-enter all motor and application parameters before the drive can be safely returned to service.

Several important lessons come from this example. First, reset procedures are highly model-specific; never assume that one ABB drive behaves like another just because the faceplates look similar. Second, ABB expects you to use documented parameter-driven mechanisms for resets, not obscure sequences of button presses or power cycles. Third, resetting is only half of the work. The more time you invest in documenting and understanding your configuration before the reset, the faster and safer the reconfiguration will be afterward.

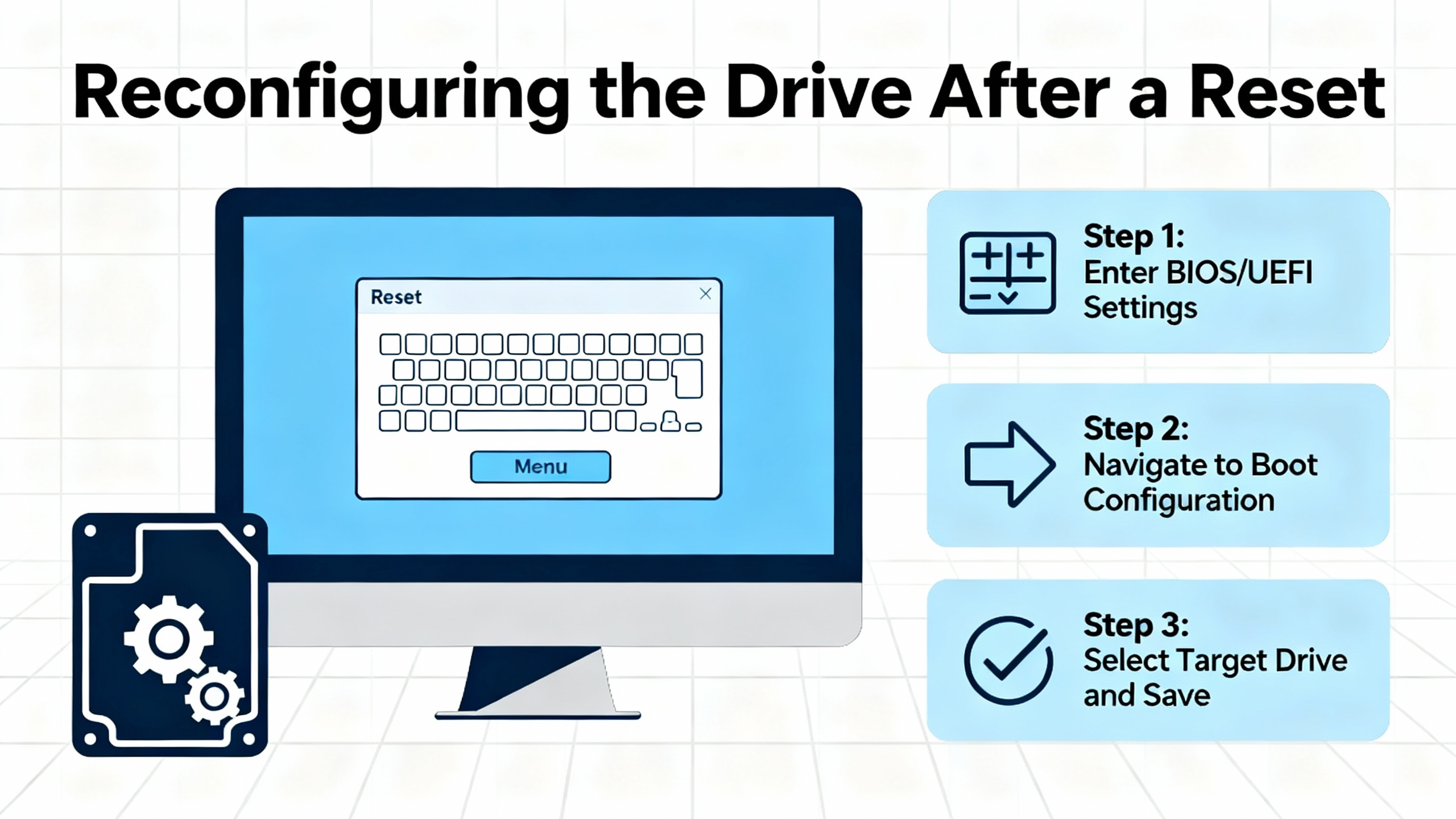

A factory reset returns the drive to a generic, out-of-the-box state. To restore reliable operation on your process, you must rebuild a configuration that is consistent with both the motor and the application. I like to think of this in three layers: motor data, application behavior, and integration.

Motor data comes first. Enter the rated voltage, current, base frequency, speed, and power factor exactly as they appear on the motor nameplate. Confirm the number of poles and any special characteristics the drive expects. Accurate motor data is essential for current limits, thermal models, and vector control to work correctly. Once this is done, verify rotation direction at low speed with no load if possible, and correct the output phasing if needed.

The application behavior layer covers how the drive should ramp, start, stop, and protect the load. Configure acceleration and deceleration times that make sense for the inertia of your driven machine. For pumps and fans, these can often be longer to reduce mechanical stress and avoid overvoltage during deceleration. Set minimum and maximum speed limits that respect process requirements and safety margins. Define how the drive should respond to trips and alarms. On some ABB platforms, you can enable automatic fault reset for transient issues. For example, the ACS580 supports an auto-reset function that can retry after certain faults without manual intervention. When you use such features, always confirm that mechanical and safety interlocks have been designed with automatic restart in mind.

The integration layer ensures the drive communicates correctly with the rest of your system. Map digital inputs for start, stop, enable, and interlock signals. Configure analog inputs for speed or torque references, including scaling and offset. If the drive communicates over fieldbus protocols such as Modbus or BACnet, set the correct addresses, baud rates, and data mappings, using ABBŌĆÖs manuals as the authoritative source. Verify that status words, alarms, and key measurements are exposed to your automation system so that future troubleshooting does not require guesswork at the keypad.

Throughout this reconfiguration, resist the temptation to ŌĆ£tune by trial and errorŌĆØ without documentation. Every time you change a parameter, note what you changed and why. ABB and third-party reliability advisors emphasize documenting parameter sets and revisions as part of standard operating procedures. This discipline pays off later when a drive fails and you need to rebuild a configuration, or when a colleague inherits a system that you commissioned.

Many modern ABB drives include options for automatic fault reset or automatic restart after a power interruption. These features are attractive because they can reduce nuisance downtime. A drive that trips on a brief undervoltage, for example, may be able to clear the fault and restart the motor once the line stabilizes. The ACS580, as demonstrated in training videos from industrial distributors, allows you to configure how many auto-reset attempts the drive will make and how long it waits between them for certain non-critical faults.

Used correctly, these functions can help processes ride through minor disturbances. Used carelessly, they can create unexpected motion in equipment that operators believe is stopped. Before enabling auto-reset, verify that all emergency stop circuits, interlocks, and guarding meet your safety requirements even if the drive restarts itself. In applications where a sudden restart could endanger personnel or damage equipment, it is often better to require a manual reset and a conscious operator action to resume operation.

If you observe the same fault recurring repeatedly despite auto-reset, treat that as a reliability signal rather than a nuisance. Disable auto-reset for that condition and investigate the underlying issue. Repeated overcurrent trips may indicate a mechanical problem. Frequent overvoltage trips during deceleration may mean that braking hardware is inadequate. Automatic reset is not a substitute for root-cause analysis; it is simply a convenience once the underlying system is known to be stable.

Not every ABB drive fault is caused by bad parameter settings, but poor maintenance often masquerades as a configuration problem. Dust, moisture, and loose connections appear again and again in drive maintenance literature as leading causes of failure. They also contribute directly to the fault codes you see and to the stress that shortens the life of internal components that store and process parameters.

In many mechanical rooms and industrial spaces, VFDs are mounted in NEMA 1 vented enclosures. These enclosures allow airflow but also invite dust. Over time, dust accumulation blocks vents, insulates heat sinks, and traps moisture. The result is higher internal temperatures, which accelerate aging of electrolytic capacitors and reduce the life of cooling fans. Manufacturers and service providers report typical fan lives on the order of tens of thousands of hours, with proactive replacement around the five to seven year mark being common practice on critical drives. Capacitors also have a finite life, often on the order of five to ten years under typical thermal stress, and should be tested and replaced according to ABBŌĆÖs guidance.

Keeping the drive dry is just as important. Stories from the field include NEMA 1 drives mounted below dehumidifiers or in locations where condensation drips onto circuit boards, leading to corrosion within months. In damp or condensing environments, a sealed NEMA 12 enclosure with appropriate heaters is a better choice. Even small amounts of moisture can create leakage paths on control boards, resulting in ground faults or intermittent internal errors that are very difficult to diagnose if you focus only on parameters.

Electrical connections deserve the same attention. Thermal cycling and vibration can loosen terminations over time. Loose power lugs can cause arcing, which leads to local overheating, overvoltage on the DC bus, and nuisance trips. Loose control wiring can cause start or speed reference signals to flicker, leading to unexplained starts, stops, or speed swings. Instead of routinely retightening every terminal, which can damage hardware, use tools such as infrared thermometers or thermal imaging to identify hot spots, and then correct only genuinely loose or damaged terminations with the drive safely de-energized.

Preventive maintenance programs from ABB and service companies emphasize combining these basic practices with scheduled inspections and component replacements. Typical programs involve regular visual inspections and cleaning, periodic verification of fan operation and filter cleanliness, annual inspection and retorque of major terminations, and mid-life testing or replacement of capacitors and fans. Done consistently, such a program can extend drive life into the ten- to fifteen-year range or beyond while minimizing unplanned downtime.

Equally important is the maintenance of your configuration information. Treat parameter backups as part of your preventive maintenance. Keep copies of parameter sets for all critical drives, including version information, in a controlled repository. Update those backups when changes are made, and label them with the date and reason for modification. This practice ensures that when a control board fails or a drive requires replacement, you can restore a known-good configuration rather than starting from scratch or attempting to reconstruct logic from memory.

There is a point in every difficult fault where it becomes more cost-effective to call in outside expertise than to keep experimenting. Persistent internal faults, repeated trips that continue after correct parameterization and mechanical checks, and evidence of physical damage such as burned boards or bulging capacitors all fall into this category. At that point, leveraging ABBŌĆÖs technical support or an experienced drive service provider is not a sign of failure; it is a reliability decision.

ABBŌĆÖs own documentation and independent service firms highlight the value of combining on-site inspection with access to diagnostic tools, spare parts, and up-to-date firmware. Specialists can test boards, replace fans and capacitors, verify drive sizing, and recommend upgrades where a legacy platform no longer fits the reliability or safety requirements of the plant. In many cases, a structured maintenance and upgrade plan costs less over the life of the plant than repeated emergency replacements and ad-hoc parameter resets in the middle of the night.

When an ABB drive faults, a quick reset is tempting, but long-term reliability comes from understanding and preserving your parameter sets, not erasing them. Treat fault codes as valuable clues, not annoyances. Back up parameters as carefully as you back up control programs. Use factory resets sparingly and deliberately, only after you have captured what the drive already knows and only with a clear reconfiguration plan. Combine that discipline with solid preventive maintenance on the physical drive, and your ABB VFDs are far more likely to deliver the quiet, reliable service that good power systems are built on.

Leave Your Comment