-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Chemical processing plants live at the intersection of high hazard, high complexity, and high regulatory exposure. A single unexpected trip of a reactor agitator, a stuck control valve, or a loss of power to an analyzer can turn a routine batch into a safety event. From a power system specialistŌĆÖs perspective, safe chemical operations are as much about keeping the control, protection, and safety layers energized and coherent as they are about the chemistry itself.

Schneider Electric has been vocal about an industry shift away from rigid, hardware-centric control toward open, software-centric ŌĆ£universal automationŌĆØ for the chemical sector. At the same time, the broader market data on automation in chemicals, manufacturing, and process industries all point in the same direction: plants that embrace integrated automation and robust power protection are safer, more efficient, and better prepared for volatility.

This article looks at Schneider-style automation concepts through the lens of safe chemical operations, with particular attention to how control architectures should be paired with UPS, inverters, and power protection equipment to keep critical safety functions online when the plant is under stress.

The chemical industry produces everything from polymers and solvents to pharma intermediates for downstream sectors such as agriculture, construction, transport, healthcare, and consumer goods. As Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs own industry analysis highlights, these processes are resource-intensive and extremely sensitive to small variations in feed quality, temperature, pressure, or catalyst performance. A minor deviation at the reactor can cascade through separation, storage, and packaging.

Several structural pressures are reshaping the sector. Sustainability and environmental scrutiny are rising, digitalization and autonomous systems are moving from pilot projects into core operations, global trade patterns are shifting, and producers are investing heavily in renewable and bio-based chemistries. At the same time, over two-thirds of North American chemical facilities operate with aging assets, and many run on legacy proprietary automation systems that are increasingly difficult to maintain and integrate.

These ŌĆ£automation islandsŌĆØ create both safety and reliability risk. When plant control is tied to vendor-specific hardware and opaque interfaces, even simple changesŌĆösuch as adding a new safety interlock or connecting condition monitoring data from a critical pumpŌĆöcan be costly and slow. The result is a landscape where many operators see automation as a necessary cost, rather than as a strategic enabler of safer, more flexible operations.

Automation-focused studies in the chemical sector and beyond reinforce the stakes. Analyses of automation in manufacturing and chemicals note that digital transformation with automation, real-time monitoring, and predictive maintenance can cut unplanned downtime significantly, while automation in hazardous industries consistently reduces operator exposure and human error. Articles on automation in chemical manufacturing emphasize that automated control can continuously monitor pressure, temperature, flow, and concentrations, and automatically adjust or shut down processes to prevent fires, explosions, and toxic releases. In other words, automation is not an optional overlay; it is a core risk-control layer.

Across industries, automation is commonly defined as the use of technology to perform tasks with minimal human intervention, primarily to increase efficiency, reduce costs, and improve accuracy. In the chemical context, that definition is incomplete unless safety and regulatory compliance sit at the center.

Process automation in chemicals spans a hierarchy of systems. At the field level, sensors and actuators measure and manipulate key parameters such as temperature, pressure, flow, and level. Above that, distributed control systems, PLCs, and SCADA platforms orchestrate unit operations, recipes, and interlocks. Robotics may handle repetitive material movements, and IoT devices collect high-frequency condition data for analysis. Articles on chemical manufacturing automation stress that integrating these layers with AI and machine learning enables plants to find patterns in large process datasets, optimize operating windows, and anticipate failures before they become incidents.

Safety benefits are fundamental. Industry sources focused on chemical automation explain that automated systems reduce manual work in hazardous areas, minimize human error, and provide continuous monitoring. When configured correctly, they enforce safety limits and trigger alarms or shutdowns if the process approaches unsafe conditions. Automation in chemical manufacturing has been framed not as an optional efficiency play, but as a strategic necessity for meeting strict environmental and safety regulations while controlling costs.

Standards are an important part of this safety picture. Professional guidance for chemical engineers emphasizes the role of automation and process control standards developed by the International Society of Automation and adopted by bodies such as ANSI and IEC. These standards, along with references like the National Electrical Code and guides to the automation body of knowledge, provide requirements and best practices for handling abnormal and hazardous situations, interpreting documentation such as piping and instrumentation diagrams, designing effective humanŌĆōmachine interfaces, and organizing batch control software. In practice, safe automation means aligning both the control logic and the supporting power and communication infrastructure with these standards, so the plantŌĆÖs protection layers behave predictably under stress.

Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs own writing on the future of industrial automation in chemicals starts by acknowledging a hard truth: the industryŌĆÖs installed base of proprietary automation has created vendor lock-in, fragmented islands of control, and brittle interfaces between operations technology and information technology. In this environment, many end users view automation upgrades as disruptive, risky projects that threaten uptime, rather than as opportunities to improve safety and resilience.

The proposed answer is a shift to software-centric ŌĆ£universal automation.ŌĆØ In this model, control applications are modular, hardware-agnostic, and portable across devices. Instead of binding control logic tightly to a particular PLC or DCS platform, the logic runs on a shared, standardized runtime environment that different vendors implement. Hardware becomes a flexible, replaceable layer beneath standardized software.

Schneider Electric and several partners founded the Universal Automation Organization to advance exactly this idea. The organization provides a containerized automation software layer based on the IEC 61499 standard, using event-driven function blocks. The architecture explicitly separates the device model, control application model, and system model so they can follow independent lifecycles. This separation allows chemical producers to update or redeploy control applications without being trapped by the lifecycle of any one hardware platform.

For chemical plants, this universal automation approach supports several safety-relevant goals. It makes automation systems more flexible, so processes can be reconfigured when feedstocks or environmental constraints change. It promotes portability, so applications can move from older hardware to newer platforms without complete redesign. It fosters modularity, so control applications can align with process and equipment modules from multiple vendors. And it emphasizes interoperability and openness, so safety-critical logic can be inspected and modified regardless of the hardware supplier.

Major end users, including global energy and chemical companies, are backing these plug-and-produce ecosystems, with the aim of unifying machine, batch, and continuous controls. While published articles do not yet provide detailed quantitative safety metrics, the qualitative intent is clear: to give operators more agility and reliability while protecting long-term investments in automation.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs standpoint, this kind of software-centric architecture is only half of the equation. The other half is powering it in a way that makes safety reactions predictable, even in the worst electrical disturbances.

When a plant modernizes its automation but continues to rely on weak or unprotected power for its control and safety layers, it creates a brittle system. The logic may be sophisticated, but it is only as reliable as the energy feeding it.

Chemical operations impose harsh electrical demands. Large motors for agitators and compressors, high-inrush loads, and switching of inductive equipment can cause voltage dips, harmonics, and transients. External disturbances from the grid can introduce additional sags and swells. Without appropriate power conditioning and backup, automation and safety systems may reset or misoperate at exactly the wrong moment.

This is where industrial UPS systems, inverters, and power protection equipment come into play. In a well-designed chemical plant, these systems form a dedicated backbone for critical loads such as distributed control servers and controllers, safety instrumented systems, emergency shutdown logic, analyzers, critical networking and communications, and control room infrastructure. By isolating these loads from raw plant power, a UPS and inverter chain provides ride-through for short disturbances and, when paired with generators or other backup sources, can sustain safe operation or orderly shutdown during extended outages.

Experience across industrial facilities shows that plants which treat power protection as part of their functional safety strategy, rather than as a generic electrical accessory, reduce spurious trips, nuisance alarms, and loss of view or control during upsets. The principle is straightforward: if a loss of control power can create or exacerbate a hazard, then the design of that power system is a safety design problem.

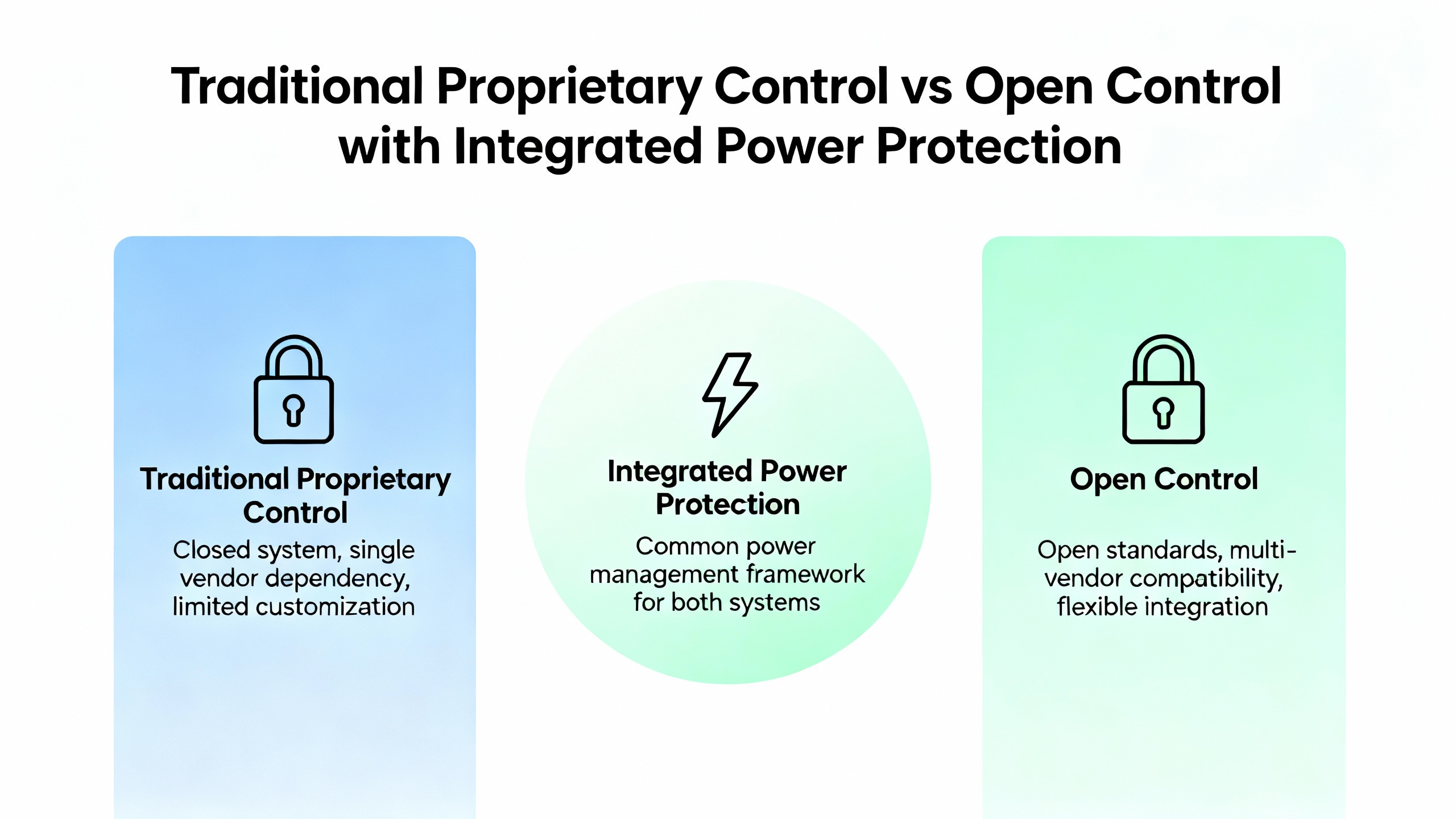

The difference between older hardware-centric architectures and modern open ones with robust power protection can be summarized along a few critical dimensions.

| Dimension | Traditional Proprietary Automation | Open, Universal Automation with Integrated Power Protection |

|---|---|---|

| Lifecycle | Control logic tightly bound to specific hardware; upgrades often require full system replacement. | Control apps portable across hardware; device and application lifecycles decoupled. |

| Vendor Lock-In | High; changes and safety updates often depend on a single vendorŌĆÖs roadmap. | Reduced; standardized runtime allows multi-vendor ecosystems and easier migration. |

| Safety Modifications | Complex to implement across islands of automation; validation cycles are long. | Modular blocks aligned with process units; changes can be isolated and validated per module. |

| Power Integration | Control power sometimes treated as ordinary plant load, vulnerable to disturbances. | Critical control and safety loads clearly segmented and fed from dedicated UPS/inverter systems. |

| OT/IT Integration | Rigid interfaces between control and enterprise systems; data silos are common. | Software-centric design and IoT integration improve data flow for analysis and predictive maintenance. |

The column on the right aligns closely with the design imperatives highlighted by Schneider Electric and other industrial automation leaders: flexibility, portability, modularity, interoperability, and strong links between OT and IT. From a power perspective, it also underscores the need to treat critical control and safety power as a distinct, protected subsystem, not just another feeder on a motor control center.

Translating these ideas into a project requires a disciplined approach that combines automation, process safety, and electrical design.

It begins with a clear view of process hazards and safety functions. For each unit operation, the engineering team identifies credible worst-case scenarios, such as overpressure in a reactor, loss of cooling in an exothermic step, or overfilling in a storage tank. For each scenario, they define the necessary safety instrumented functions, along with independent protective layers such as relief devices and physical containment. Automation references from the chemical sector stress how automation can monitor and respond to these abnormal situations, but that response depends on the availability of the sensors, logic, and final elements involved.

Next, the team segments and prioritizes loads. Control and safety systems that must operate through disturbances are grouped into clearly defined critical power zones. These might include central controllers and servers, safety logic solvers, critical communication infrastructure, key I/O panels, and analyzers whose loss would blind operators to process conditions. Each of these zones is then fed from UPS and inverter systems sized for the expected duration of disturbances and coordinated with generation or other backup sources.

At the same time, the control applications themselves are designed in modular, hardware-agnostic fashion. Drawing on the universal automation concepts Schneider Electric promotes, control engineers structure logic as reusable function blocks aligned with equipment modules such as reactors, distillation columns, and packaging lines. In a universal automation runtime, these blocks can be deployed on different physical devices over time without rewriting core logic. For the plant, this means that if a particular controller platform reaches end of life, the safety and control strategies do not have to be reinvented.

Data and analytics are then woven through this architecture. Articles on chemical manufacturing automation highlight the value of real-time data for quality control, predictive maintenance, and continuous optimization. With open, interoperable systems, data from field devices, controllers, and power protection gear can be fed into analytics platforms. Condition data from UPS systems, for instance, can signal when battery health is degrading, while power quality metrics can reveal disturbances that threaten sensitive instruments.

Throughout, change management and workforce training are critical. Broad surveys of employees working with automation, published by management and technology research outlets, show that well over ninety percent report higher productivity when automation is implemented properly, and a large majority say it improves collaboration and reduces errors. However, those same sources emphasize the importance of communication and upskilling to address fears about job loss and to help staff move into more strategic roles. In a chemical plant retrofit, operators and maintenance technicians must be trained not only on new control interfaces but also on the implications of UPS and power protection for emergency procedures. They need clarity on which systems are on protected power, how long they will run during outages, and what the expected operator actions are in different scenarios.

Once a plant has a modern control and power protection backbone, the real safety and reliability gains come from how it uses the resulting data.

Automation-oriented sources for chemical manufacturing and industrial automation point to several data-driven advantages. Automated quality control and real-time sampling ensure that key variables stay within tight limits and that deviations are corrected early, reducing the risk of off-spec or unsafe product batches. Automation also reduces waste by optimizing ingredient usage and minimizing rework and disposal. IoT-enabled sensors on pumps, mixers, and heat exchangers generate rich time-series data that supports predictive maintenance. Studies in chemical plant engineering and digital transformation note that AI-driven predictive maintenance can reduce unplanned downtime by up to about thirty percent, which directly improves both safety and profitability.

Power protection equipment can contribute to this analytics layer. Modern UPS systems and inverters often offer detailed event logs, alarms, and performance data. By integrating this information into the same data environment as process variables, plants can correlate power quality events with process upsets, nuisance trips, or anomalies in instrument behavior. Automation surveys repeatedly highlight the importance of unifying data across systems into a single source of truth, so that automation can trigger intelligent actions in real time. For a chemical plant, this might mean automatically adjusting operating limits when power conditions are marginal, or triggering preemptive maintenance work orders when power disturbances exceed predefined thresholds.

Broader industry analyses show that connecting automation with analytics and AI enables immediate reactions to changing conditions and more personalized responses in customer-facing applications. In the chemical context, this translates into dynamic optimization of setpoints, real-time adjustment of batch parameters, and smarter scheduling of energy-intensive operations to align with power system constraints. The underlying principle is the same: automation, analytics, and reliable power form a feedback loop that continually drives risk down and performance up.

Many chemical facilities face the challenge of modernizing automation and power systems while operating under tight budgets and a shortage of experienced engineering leaders. Studies on chemical plant engineering between 2023 and 2025 highlight that more than two-thirds of chemical manufacturing assets in North America are aging, regulatory compliance costs have risen significantly, and there is a shortage of leaders who can bridge process engineering, digital technologies, and regulatory demands.

In this context, Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs universal automation vision is as much about modernization strategy as it is about technology. By decoupling control applications from specific hardware, plants can migrate incrementally. A typical pathway might start with a high-priority unit where safety, downtime, or product flexibility pressures are greatest. Engineers deploy a universal automation layer on suitable hardware, integrate it with a robust UPS-fed power backbone, and establish OT/IT data integration. Once the benefits are proven and staff are comfortable, the approach expands to adjacent units.

Executive-level guidance suggests that modernization efforts should be tied directly to strategic goals around safety, sustainability, and resilience, rather than treated as isolated capital projects. Specialist search and consulting firms in the chemical sector emphasize the value of leaders who understand both engineering and digitalization. From a power and control standpoint, this means appointing champions who can articulate why investments in UPS, open automation, data infrastructure, and training are essential risk-management tools, not optional extras.

A power system designed around safe chemical operations must meet several practical criteria.

It needs clear separation between critical and noncritical loads. Control and safety systems, communication networks, and essential environmental monitoring must reside on well-defined protected buses. These are fed by UPS systems sized not just for steady-state load, but for inrush currents of downstream equipment, expected outage durations before generators start, and the cumulative effect of ride-through events during switching.

The system must consider the specific nature of chemical loads. For instance, valves and actuators in hazardous areas may be fed through intrinsically safe or explosion-proof circuits, and the power system architecture must maintain these protections even when routed through UPS and inverters. Packaging, loading, and unloading systems that handle flammable or toxic chemicals may require additional power quality controls to avoid spurious sensor trips or nuisance shutdowns during vehicle movements or static discharge.

Maintenance and testing strategies should be automated where possible. The same automation platforms that coordinate batch operations and safety interlocks can schedule and record regular UPS battery tests, inverter self-checks, and transfer switch exercises. Automation vendors, including those focused on chemicals, highlight the power of using real-time and historical data for predictive maintenance. Applying those principles to power protection equipment reduces the likelihood that an outage reveals a dormant failure in the safety power path.

Finally, the design must support graceful degradation. No power system can guarantee infinite availability. The objective is that when failures occur, they do so in a controlled, predictable way that supports safe plant behavior. That may mean prioritizing safety logic solvers and communications over historian servers, or maintaining powered access control to critical rooms while shedding less essential loads. By explicitly linking load prioritization to the plantŌĆÖs hazard analysis and safety case, engineers ensure that power protection contributes directly to risk reduction.

How does universal automation actually improve safety in a chemical plant?

Open, hardware-agnostic automation frameworks allow safety functions and control logic to be designed as modular blocks aligned with process units and equipment. Because these blocks are portable across hardware platforms, plants can update or migrate safety-related control without wholesale rewrites and with less dependence on a single vendorŌĆÖs roadmap. Combined with industry standards for alarm management, abnormal situation handling, and humanŌĆōmachine interfaces, this modularity makes it easier to implement, validate, and maintain consistent safety behavior as the plant and its equipment evolve.

If a plant already has standby generators, why invest in UPS and inverters for control systems?

Generators address medium to long interruptions, but they do not eliminate short sags, swells, and transients, and they usually need time to start and synchronize. Sensitive control and safety systems can trip or reset during these events, which may occur during grid disturbances or generator transitions. UPS and inverter systems bridge these gaps, providing clean, stable power throughout the disturbance and until backup sources are fully online. In a chemical plant, that continuity can be the difference between a controlled shutdown and a loss of view or control at a critical moment.

How can plants justify the cost of combined automation and power protection upgrades?

Research on automation in business and industrial settings shows broad agreement that automation improves productivity, reduces errors, and enhances employee satisfaction. In chemical manufacturing, qualitative and quantitative studies highlight reductions in unplanned downtime, improvements in quality, and better compliance when automation and monitoring are deployed effectively. When engineering teams factor in the avoided costs of incidents, regulatory penalties, unplanned outages, and product losses, investments in open automation, UPS-backed control power, and data integration are best viewed as core risk management and resilience measures rather than discretionary spending.

Robust chemical operations depend on more than good chemistry and competent operators. They require an automation architecture that can evolve with the plant, and a power system that keeps the protection layers alive under the harshest conditions. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs push toward universal, software-centric automation aligns with that need, but its full value emerges only when it is paired with disciplined power protection design. For chemical producers prepared to tackle both sidesŌĆöcontrols and powerŌĆöthe payoff is safer, more resilient, and more adaptable operations for the long term.

Leave Your Comment