-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

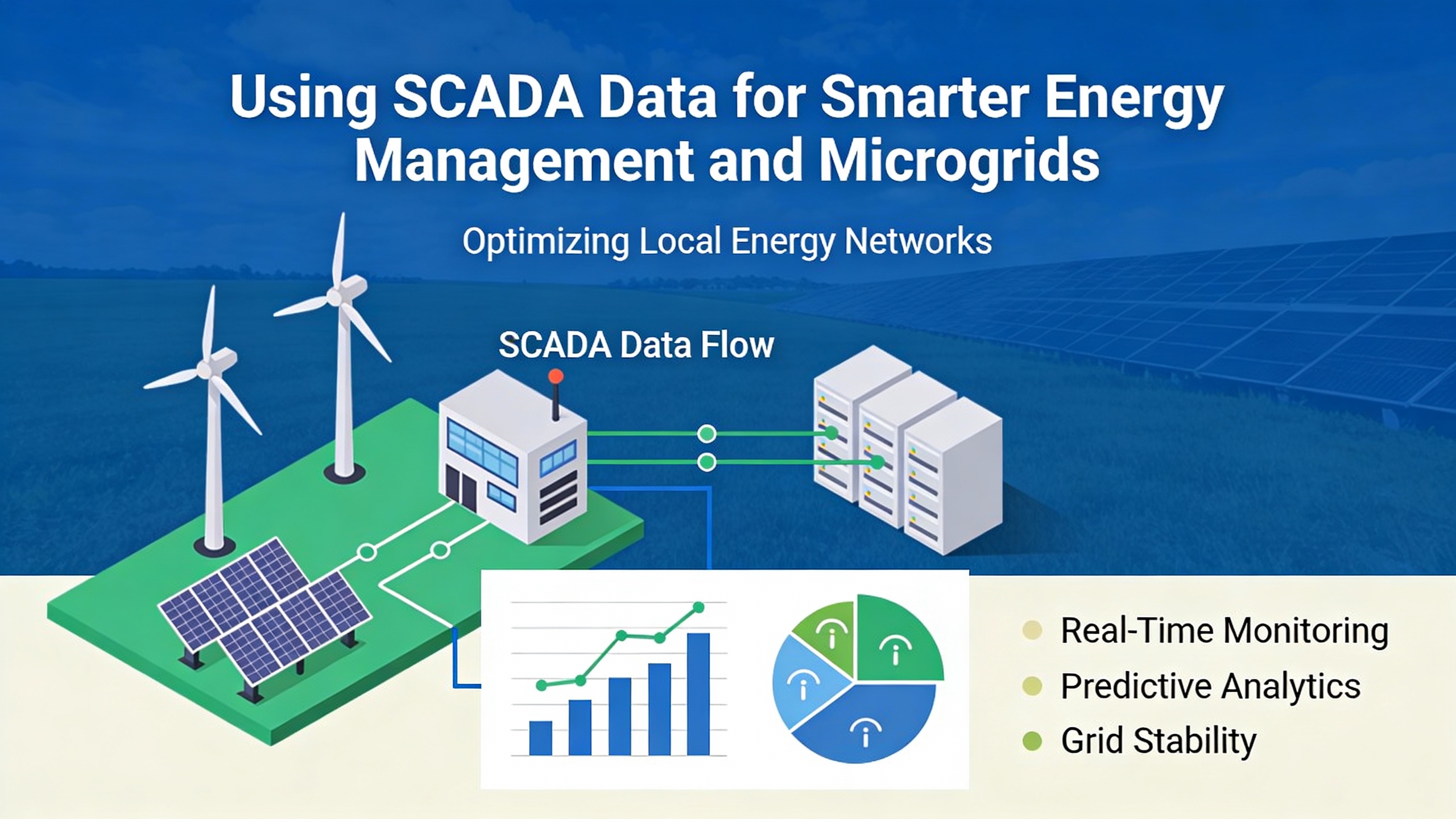

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition, or SCADA, has quietly become the central nervous system of modern wind and solar facilities. When it works, grid codes are met, inverters behave, batteries respond, and UPS and protection gear see a stable, predictable network. When it does not, you get hidden energy losses, nuisance trips, cybersecurity exposure, and difficult conversations with grid operators and investors.

Across case studies from providers such as Power Factors, Inductive Automation, Vertech, Australian Control Engineering, Nor-Cal Controls, and others, the same pattern keeps appearing. Successful renewable operators use SCADA not just as a data viewer, but as a supervisory control layer tightly coupled to plant controllers, energy management, and cybersecurity. This article looks at what that actually means for wind and solar owners, and how to make SCADA a reliability asset instead of another fragile system.

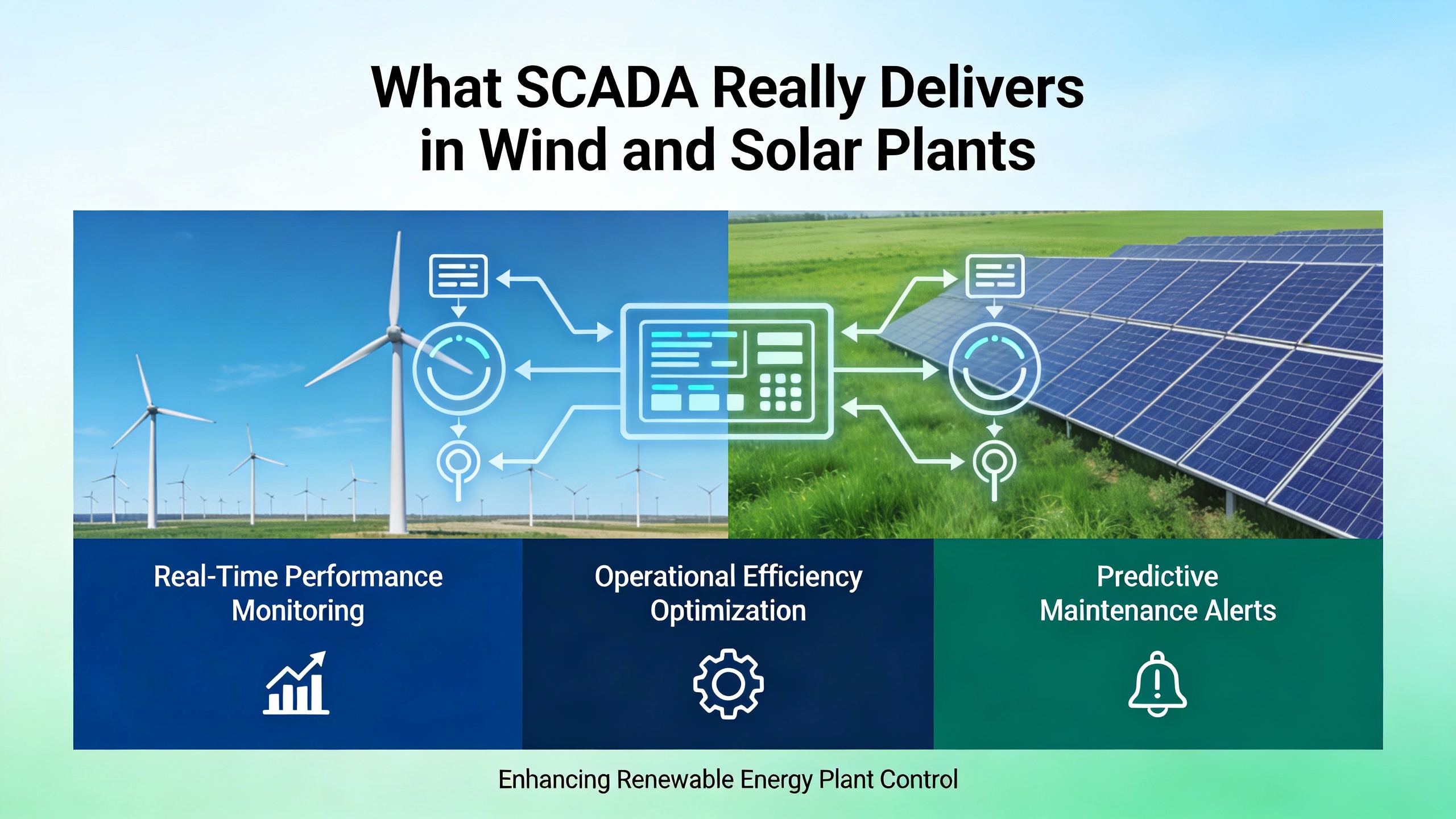

Most operators first meet SCADA as an HMI screen and some alarms, but the real value is deeper. Multiple sources, including DPS Telecom, Mikrodev, Soleos Energy, and academic work on microgrids, describe SCADA as an integrated hardware and software platform that collects data from field devices, issues control commands, maintains a historical database, and provides alarms and operator dialogue.

In wind and solar, SCADA sits on top of remote terminal units, programmable logic controllers, and intelligent electronic devices. It gathers voltages, currents, power, weather conditions, breaker status, inverter states, battery state of charge, and more. DPS TelecomŌĆÖs clean energy guidance points out that in wind farms this usually includes anemometers, wind direction sensors, tachometers, and power meters at each turbine, while in solar plants it focuses on irradiance, panel temperature, and DC and AC output. All of that data is moved over industrial protocols such as Modbus or DNP3 to a central master station where operators see real-time behavior and alarms.

Mikrodev calls SCADA the ŌĆ£invisible brainŌĆØ of modern energy management, because it does more than display values. It enables remote control of switchgear and generators, generates performance and cost reports, and accelerates fault detection through instant alerts. Academic work on SCADA for renewable microgrids describes three decision modes that this supervisory layer supports: real-time control for immediate response, real-time based optimization for tuning setpoints and protection, and offline analysis for planning, training, and post-event investigation. That combination of control, data, and decision support is what turns raw measurements into reliability and revenue protection.

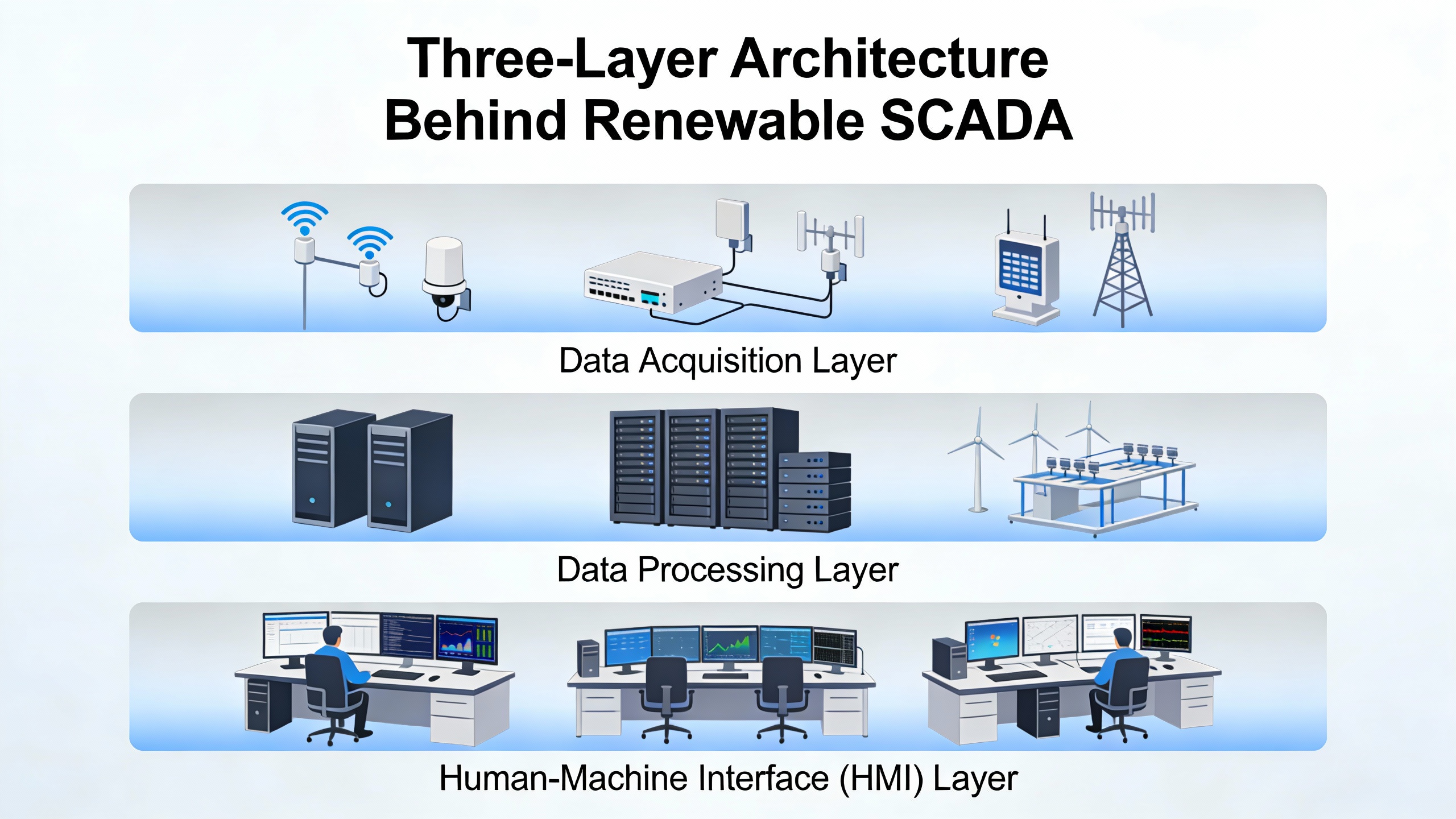

Solar-specific guidance from Soleos Energy and broader research on SCADA architectures converge on a simple but powerful structure. There is a field layer with the physical equipment, a communication layer that transports data and commands, and a supervisory layer where SCADA servers, HMIs, historians, and analytics live. A Nigerian renewable SCADA study and the ScienceDirect microgrid work both emphasize that this layered model is what makes systems reconfigurable and ready for evolving mixes of wind, solar, batteries, and loads.

A concise way to think about the architecture is shown below.

| SCADA layer | Typical components in wind/solar plants | Role in reliability and performance |

|---|---|---|

| Field layer | PV modules, string combiner boxes, inverters, wind turbines, sensors, meters, RTUs, PLCs, protection relays, BESS interfaces | Measure and act on real-world conditions; where faults actually originate |

| Communication | Fiber rings, Ethernet switches, managed VLANs, radios, cellular or LPWAN links; protocols such as Modbus, DNP3, IEC 61850; VPNs and firewalls | Move data and commands securely and reliably between field and control layers |

| Supervisory | SCADA servers, HMI consoles, data historians, reporting and analytics, local EMS and PPC, remote access gateways | Provide visibility, alarms, automation logic, and decision support for operators |

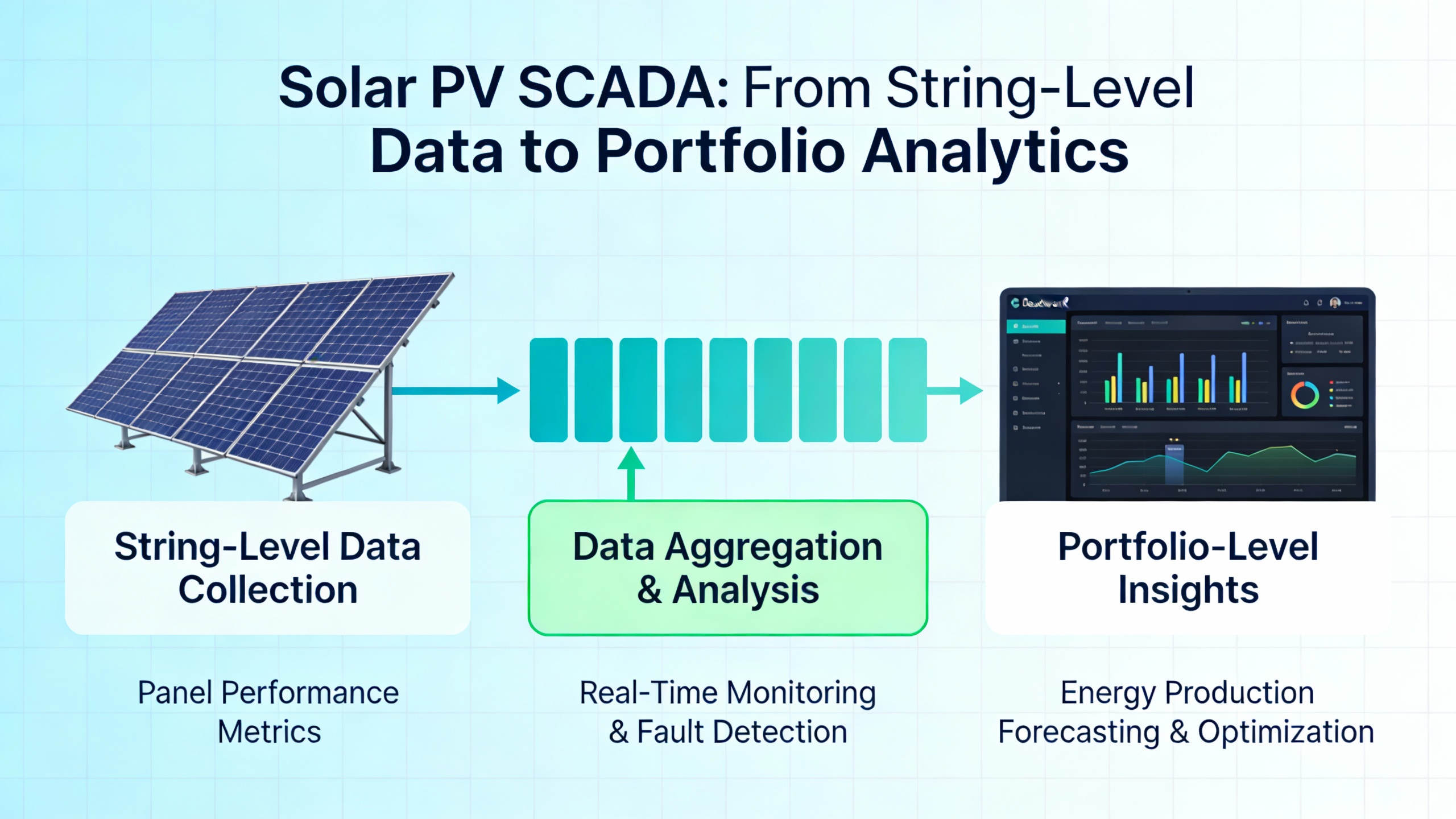

Soleos EnergyŌĆÖs description of solar SCADA makes it very clear that the field layer now extends from small rooftop arrays up to one hundred megawatt parks. As you scale, you cannot rely on manual inspection. Instead, string-level monitoring, inverter data, grid interface meters, and weather stations feed a historian that computes KPIs such as performance ratio, capacity utilization factor, and specific yield. Academic work on NigeriaŌĆÖs renewable systems uses a similar three-tier model but stresses openness and programmability so that wind, hydro, and photovoltaic generators, plus batteries and local networks, can be added or simulated without rewriting the platform.

A case study from Power Factors illustrates how this architecture looks in practice. Two utility-scale solar plants in Texas use a combination of a power plant controller, a local energy management system, and a local SCADA layer to maintain continuous and accurate site control. The combined capacity exceeds 1.1 GW of solar photovoltaic generation paired with 450 MWh of battery storage. According to Power Factors, these plants are expected to power more than 200,000 homes and offset roughly 1,455,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

From a reliability and power protection perspective, the critical point is that the local SCADA is not an isolated dashboard. It works hand in hand with the power plant controller that manages grid-facing behavior, and with the local energy management system that decides when to charge or discharge the battery. Together, they optimize clean energy production, support grid stability, and ensure that downstream loads, including any critical UPS-backed systems, see a stable supply. Operators get real-time alarms and can act on them within minutes instead of waiting for field crews to report issues.

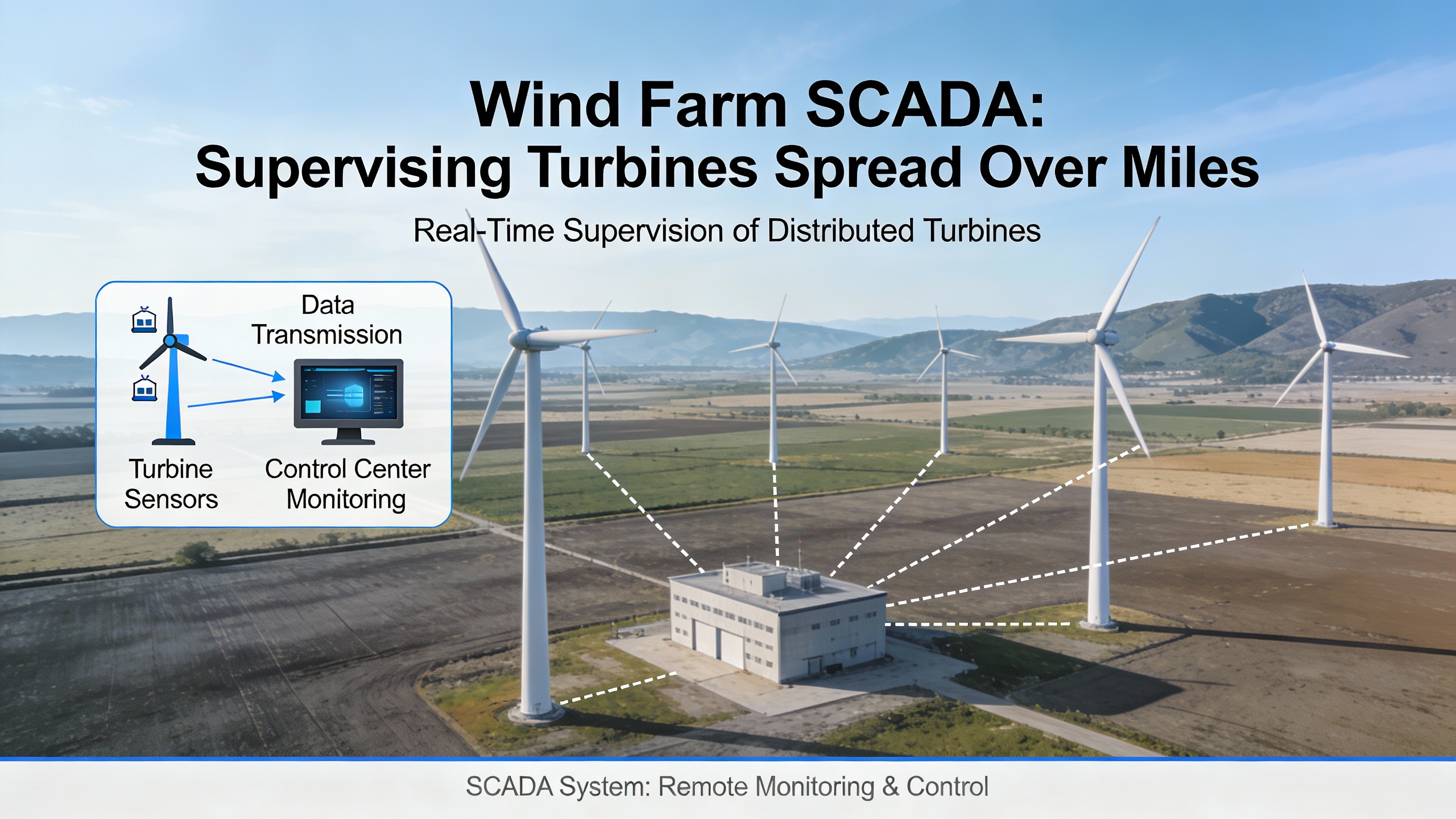

Wind facilities are classic ŌĆ£outside-the-fenceŌĆØ SCADA applications, with turbines spread over large geographic areas. DPS TelecomŌĆÖs clean energy guide explains that each turbine typically has sensors for wind speed, direction, rotor speed, and output power, all connected to remote telemetry units. These RTUs communicate back to a central master over various networks, including wireless mesh, cellular, or fiber, using protocols like Modbus and DNP3.

An article on SCADA for outside-the-fence applications from IIoT World adds the practical complication: power and communications for remote sites. Turbine controllers and sensors often rely on local batteries and small solar panels. High data volumes or frequent wireless transmissions drain those batteries quickly, which forces tradeoffs. Operators must decide how frequently to transmit data and which sensors are truly essential, or they must invest in larger batteries or more efficient communication technologies. The article notes that low-power wide area networks such as Sigfox or LoRa offer better energy efficiency but have bandwidth and coverage limitations, while traditional cellular and satellite links can be too power hungry for constant, high-frequency reporting.

For a wind operator, this means SCADA design has to consider how much real-time data is enough. If every turbine sends detailed data every few seconds over a power-hungry link, you may gain visibility but lose battery life and, eventually, the link itself. If you thin out data too much, you miss the early signatures of faults that could be caught before they trigger trips or damage. The right balance depends on the communications and power architecture, and that, in turn, depends on the SCADA platform you choose and how you configure it.

Solar plants present different challenges. They may be fenced and easier to power, but they involve thousands of strings and hundreds of inverters scattered over many acres. Inductive Automation and Vertech describe a utility-scale solar SCADA deployment where a single Ignition gateway at a site connects directly to about one hundred devices, many of them sub-gateways. Each site supervises roughly three thousand devices and over fifteen thousand I/O tags, with about two thousand of those tags being logged historically. Across five plants, the combined generation capacity exceeds two hundred megawatts.

In that project, the SCADA system goes far beyond simple trend charts. Vertech implemented a full design framework to present clear, big-picture views rather than raw data tables. They used user-defined types and templates so that creating new sites or adding new equipment is a matter of instantiating existing objects rather than writing custom logic from scratch. The reporting module does analytics on data from hundreds or thousands of panel strings and automatically highlights the lowest-performing equipment, allowing operations and maintenance teams to prioritize their work.

Soleos EnergyŌĆÖs solar SCADA guidance connects the same idea to performance KPIs. By continuously logging data and computing performance ratio, capacity utilization factor, and specific yield, SCADA becomes a tool for benchmarking and optimization. The system can flag an inverter that is slightly underperforming rather than completely tripped, or identify a group of strings affected by soiling or shading. That is exactly the kind of information that protects revenue and extends asset life, especially when you link it to maintenance programs and to protection settings for inverters and UPS feeds.

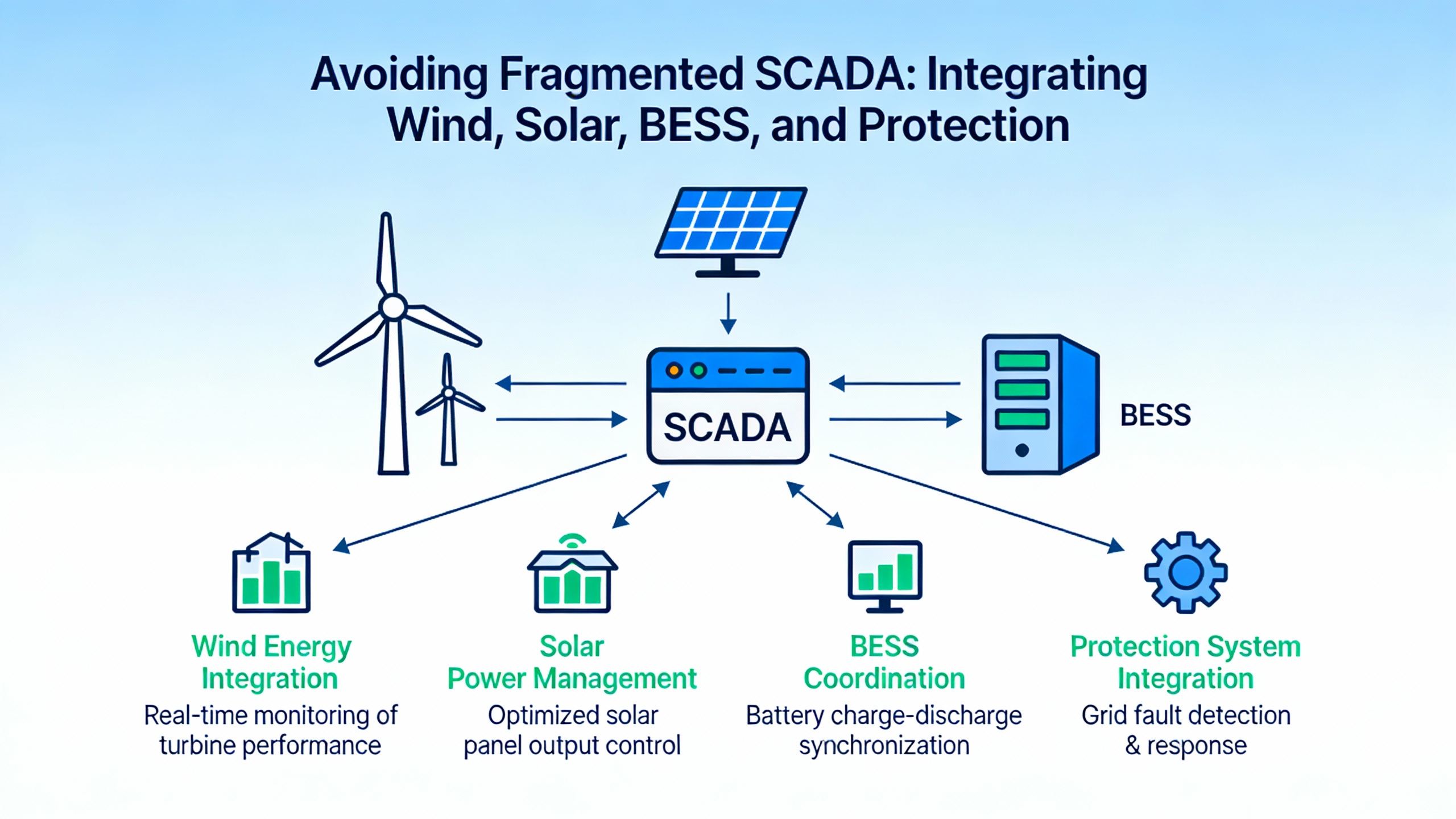

Many owners discover SCADA in stages. Inverters come with their own dashboards. The battery supplier brings an energy management interface. Meteorological equipment has its own logger. Australian Control Engineering warns that this ŌĆ£Fragmented SCADA SyndromeŌĆØ leads to operational blind spots, slower fault response, inconsistent data, and higher compliance risk. Their work on holistic SCADA integration for solar farms defines integration as consolidating inverters, battery systems, weather stations, protection relays, and grid interfaces into a single control and monitoring platform.

In one ACE project, moving to an integrated SCADA approach reportedly delivered a thirty-four percent increase in operational efficiency and a seventy-two percent reduction in major incidents, along with faster issue resolution and better grid compliance. A companion article from ACE on SCADA integration with battery storage highlights the same theme for hybrid plants. Battery systems act as a buffer between variable solar output and grid demand, storing excess energy during high production and discharging during peaks. When SCADA and battery controls are tightly integrated, operators can maximize self-consumption, reduce grid imports during high tariffs, and participate in ancillary services such as frequency regulation and demand response.

Power FactorsŌĆÖ broader discussion of renewable SCADA draws a useful distinction between local and central systems. Local SCADA focuses on individual sites and is appropriate for smaller operations. Central SCADA is purpose-built for portfolios that include solar, wind, and battery assets. It provides scalable, portfolio-wide oversight that retrofitted local systems often struggle to match. The same article points out that SCADA data underpins advanced asset performance management and AI analytics, which help operators decide when to produce, store, or sell energy and how to meet grid services requirements reliably.

From a power protection and UPS perspective, integrated SCADA also simplifies fault coordination. When grid, inverter, battery, and protection data sit in one system, it is much easier to understand why a breaker tripped or a UPS transferred to battery. You can correlate disturbances with inverter events and grid commands, and you can adjust protection settings confidently rather than guessing in the dark.

Once you accept that SCADA needs to be central rather than an afterthought, platform choice matters. Several sources provide practical guidance on what to look for.

Inductive AutomationŌĆÖs solar and storage materials describe a SCADA platform that can handle hundreds of thousands of tags across multiple sites without architectural bottlenecks. They emphasize an unlimited licensing model that allows adding sites, tags, users, and devices without incremental license fees. VertechŌĆÖs case study illustrates how user-defined types and reusable graphical templates drastically cut engineering effort when rolling out new plants. ThingsBoardŌĆÖs energy management overview highlights the benefits of integrating SCADA-style data collection and visualization with IoT analytics to identify inefficiencies, forecast demand peaks, and detect anomalies.

On the energy management side, MikrodevŌĆÖs discussion of SCADA trends points to the value of combining SCADA with artificial intelligence and big data. In their framing, SCADA is moving from rule-based control toward predictive, self-optimizing behavior. By analyzing live and historical data, systems can forecast weather-driven production in solar and wind plants, detect anomalies in vibration, temperature, and current, and support predictive maintenance that extends equipment life and prevents unplanned downtime. The ScienceDirect microgrid paper similarly describes intelligent control that uses real-time measurements and short-term forecasts to schedule distributed generators, charge or discharge storage, and shift flexible loads. Typical objectives include reducing operating energy cost, maximizing on-site renewable utilization, cutting emissions, and limiting peak demand.

For building and campus microgrids, the Nigerian SCADA optimization study emphasizes open, easily reconfigurable SCADA platforms that can operate both in live control mode and in simulation mode. That dual-mode behavior is valuable when you want to test new control strategies, protection schemes, or integrated UPS and inverter behavior before applying them to a live system. It also helps train operators without risking real equipment. The same study notes that SCADA platforms with layered architecture and programmable devices can adapt as new generation technologies or storage systems are added.

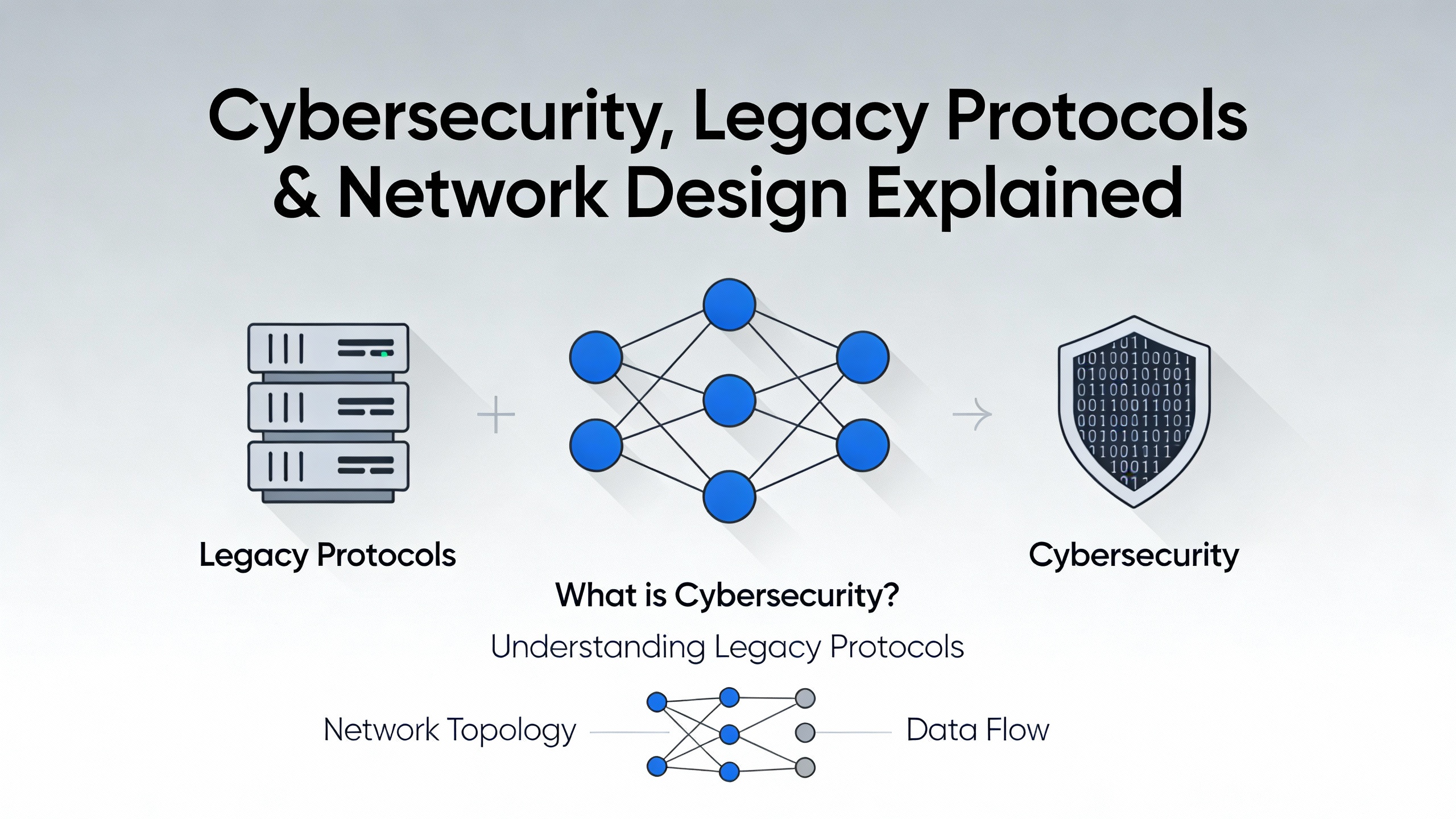

As SCADA takes on more responsibility, its attack surface grows. The Electron ProjectŌĆÖs analysis of legacy systems in renewable plants is blunt on this point. Many wind, solar, and hydro facilities still rely on older hardware and communication protocols such as Modbus, DNP3, and IEC 60870-5-104. Early or outdated versions of these protocols were designed for operational functionality and interoperability rather than security. They typically lack encryption and strong authentication. That means critical operational commands and sensitive information travel in clear text and can be intercepted or altered by attackers, with the potential for equipment malfunctions, disrupted energy production, and even grid instability.

The same article notes that enhancing security in these legacy systems is difficult and expensive. Retrofitting encryption and modern authentication often requires substantial modifications or full system replacement. Remote locations and limited connectivity further complicate regular patching and updates, leaving known vulnerabilities exposed. To mitigate these risks, the Electron Project points to the Purdue Model as implemented under IEC 62443, which segments the network into zones and conduits to support defense in depth. They also highlight zero trust network access, where every user and device, internal or external, must be authenticated, authorized, and continuously validated, and they point to technologies such as VPN tunnels and network detection and response systems for secure, monitored connectivity.

Nor-Cal Controls offers a practical view from solar PV plants. They stress that SCADA networks are high-value targets and must be isolated from corporate networks with firewalls, often via a demilitarized zone. For standard projects, they recommend two firewalls in a redundant configuration so that if one fails, the other continues to protect the SCADA network. They also warn against using unmanaged switches, which essentially put all devices on the same subnet with no real security; anyone who can plug in can access the network. Managed switches with VLANs are recommended, because they allow segmentation so sensitive SCADA components remain isolated from less critical systems.

Fiber topology is another reliability and security factor. Nor-CalŌĆÖs guidance suggests a collapsed ring as a cost-effective way to maintain redundancy; inbound and outbound fiber loops share the same bundle, roughly halving the total fiber length, and the loss of a single inverter or segment does not bring down the entire link. For large solar sites, they recommend single-mode fiber over multimode. Single-mode, which uses lasers, supports longer, more stable links of around five kilometers, roughly three miles, whereas multimode is usually limited to around two kilometers, about one and a quarter miles, and is less suitable for big, spread-out sites.

IIoT WorldŌĆÖs outside-the-fence SCADA article adds that when you rely on third-party wireless providers for connectivity, outage resolution is slower because you do not control the network. You may also need to manage multiple cellular carriers and SIM contracts, and signal strength can vary with weather and local conditions. Emerging technologies such as narrowband IoT promise more power-efficient remote communications, but the dominant standards and ecosystems are still evolving.

For an owner thinking in terms of UPS, inverters, and power protection, the message is clear. SCADA is part of the protection system now. A compromised or unreliable SCADA network can issue bad commands, hide alarms, or delay responses, turning a minor fault into a major outage. Network segmentation, secure remote access, robust fiber and switch design, and continuous monitoring are as fundamental to plant reliability as correctly sized UPS systems and properly coordinated protection relays.

SCADAŌĆÖs role does not end at monitoring and immediate control. It is also the primary data source for energy management strategies in renewable-heavy systems. ThingsBoardŌĆÖs energy management material shows how SCADA-style data collection and visualization can be combined with analytics to track consumption patterns, identify inefficiencies, forecast demand peaks, and detect anomalies. Rather than relying on periodic manual checks, operators can watch generation and load behavior in real time and act before problems become serious.

MikrodevŌĆÖs discussion of SCADA and energy management emphasizes that digital SCADA consolidates live data from across the system into a central control room. Big data analytics then convert previously idle sensor data into insights that help forecast demand and production, optimize operating hours for critical devices, and identify high-risk fault areas. By 2025, they expect smart cities and automated energy systems using SCADA, artificial intelligence, and renewables to be built around three pillars: efficiency, continuity, and security.

Research on a real microgrid for smart building applications, summarized from ScienceDirect, describes SCADA as the supervisory layer for a localized electrical network that integrates photovoltaic generation, battery storage, and controllable loads. The intelligent energy management strategy uses real-time measurements and short-term forecasts to schedule generation and storage, and to shift flexible loads. Typical objectives include minimizing energy cost, maximizing renewable utilization, reducing emissions, limiting peak demand, and maintaining comfort and power quality. Published case studies of similar SCADA-managed building microgrids often report reductions on the order of ten to thirty percent in grid electricity costs and peak demand, along with higher renewable self-consumption.

The Nigerian SCADA study on renewable integration reinforces this picture at a larger scale. It frames energy as a means to ends such as health, living standards, and a clean environment and argues that optimized SCADA-based energy flow management and broader efficiency measures are urgent as industrial demand grows. Their architecture uses SCADA to coordinate wind, hydro, and photovoltaic generators, batteries, power converters, and consumer loads, with the ability to run in live or simulation mode. That flexibility is particularly valuable when balancing centralized grid supply with local generation and storage, especially for facilities that must maintain critical loads through UPS and backup arrangements.

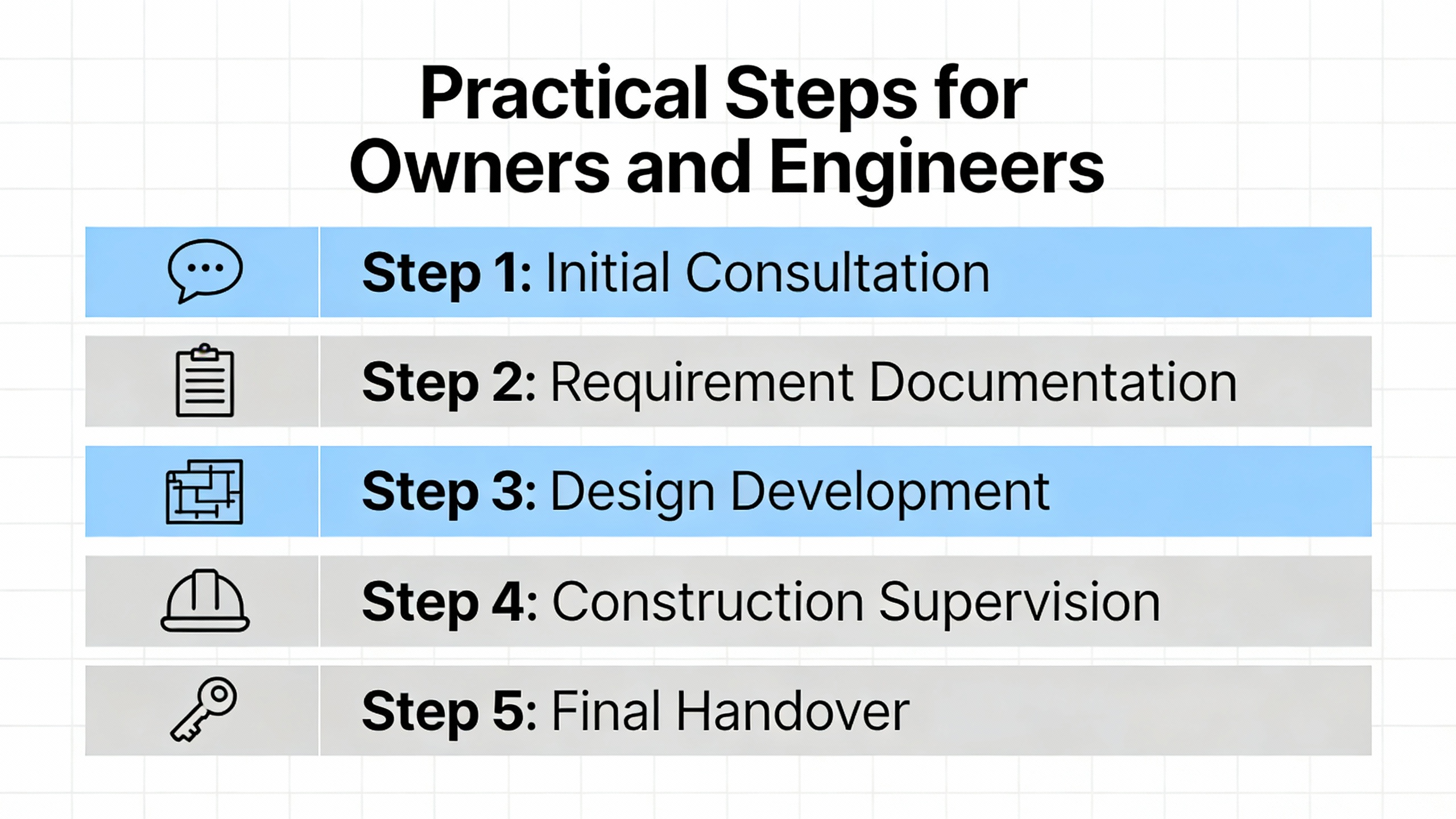

For owners and engineers responsible for wind and solar facilities, the research and case studies point to a consistent set of actions, even though each site is different.

First, treat SCADA as a core reliability system, not an accessory. In the Power Factors Texas plants and the Vertech solar fleet, SCADA is tightly integrated with power plant controllers, local energy management, and grid interfaces. That is what enables those systems to manage over a gigawatt of solar plus hundreds of megawatt-hours of storage while meeting grid requirements and serving hundreds of thousands of homes. If your SCADA is just polling a few values while inverters, batteries, and protection relays all run their own islands of logic, you will have blind spots and slower responses.

Second, design around a clear architecture. The three-layer model described by Soleos Energy and academic work is a solid starting point. Ensure that the field layer is instrumented well enough to see and control what matters, including inverter statuses, breaker states, and critical UPS feeds. Build a robust communication layer using managed switches, segmented VLANs, secure fiber topologies, and, where needed, carefully designed wireless links. Then invest in a supervisory layer that can log the right data, compute the right KPIs, and present operators with actionable information rather than noise.

Third, address cybersecurity and legacy risks deliberately. The Electron ProjectŌĆÖs warnings about unencrypted legacy protocols, along with Nor-CalŌĆÖs network segmentation and firewall recommendations, show that assumptions from older SCADA generations no longer hold. Map your SCADA network connections, isolate them from corporate IT, apply zero trust principles for remote access, and use modern monitoring tools such as network detection and response where feasible. If you rely on older Modbus or DNP3 variants without security, compensating controls such as VPN tunnels, strict access control, and segmentation become nonnegotiable.

Fourth, consolidate fragmented monitoring into integrated SCADA where possible. ACEŌĆÖs data on operational efficiency and incident reduction after moving to holistic SCADA is not unusual in the context of the other case studies from Vertech, Inductive Automation, and Power Factors. When all your key components share a single supervisory layer, it becomes far easier to perform root-cause analysis, coordinate protection and UPS behavior, and keep plants in compliance as regulations evolve.

Finally, leverage SCADA data for continuous improvement. The microgrid studies and energy management platforms described by Mikrodev, ThingsBoard, and ScienceDirect show that once you have reliable SCADA data, you can move toward predictive maintenance, optimized dispatch, and better use of storage. That is where the real, long-term reliability and cost benefits emerge, not just in catching individual faults.

Power Factors distinguishes between local SCADA, which focuses on individual sites, and central SCADA, which oversees entire portfolios. Smaller, single-site plants may operate effectively with a robust local SCADA that integrates inverters, batteries, and protection relays. As soon as you manage multiple sites or mixed technologies such as wind, solar, and storage, a central SCADA layer becomes valuable for portfolio-wide visibility, standardization, and analytics. Case studies from VertechŌĆÖs multi-plant solar deployment and Power FactorsŌĆÖ portfolio tools suggest that centralization simplifies operations and scaling.

The Electron ProjectŌĆÖs analysis of legacy protocols shows that simply adding devices around an old core can leave serious cybersecurity and reliability gaps. Older Modbus, DNP3, and IEC 60870-5-104 implementations often lack encryption and authentication, and they can be difficult to patch or retrofit. In some cases, it is possible to place secure gateways, firewalls, and VPNs around legacy systems, combined with Purdue-style segmentation and zero trust access, to reduce risk. However, if your plant is adding grid-interactive storage, complex market participation, or critical UPS-backed loads, a phased upgrade toward a modern, secure SCADA platform is usually the safer long-term strategy.

Exact numbers depend on the site, but published work on SCADA-managed microgrids summarized from ScienceDirect reports reductions on the order of ten to thirty percent in grid electricity costs and peak demand, along with higher renewable self-consumption. Australian Control EngineeringŌĆÖs integrated SCADA project for solar farms documented a thirty-four percent increase in operational efficiency and a seventy-two percent reduction in major incidents. Taken together with the performance analytics cases from Vertech and the energy management insights from Mikrodev and ThingsBoard, the evidence supports a clear conclusion: when SCADA data is used for continuous optimization rather than just monitoring, the improvements in reliability and cost are substantial.

As a power system specialist and reliability advisor, my view is simple. In wind and solar facilities, SCADA is now as critical as inverters, protection relays, and UPS systems. If you design it as a secure, integrated supervisory layer and use its data to drive decisions, it will quietly safeguard your energy production and your balance sheet for years to come.

Leave Your Comment