-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Chemical manufacturing spans basic chemicals, resins, coatings, fertilizers, and specialty formulations, but the core challenge is the same everywhere: keep highly reactive, energy-intensive processes inside tight quality and safety limits, day after day. Publications from organizations such as Minitab and the Texas Chemistry Council emphasize that consistent specification compliance, stable operations, and regulatory-ready documentation are now business-critical, not optional.

Programmable logic controllers (PLCs) sit right at the point where valves, pumps, analyzers, and drives meet the rest of the plant. They read sensors, execute control logic, and drive actuators, while providing real-time data into historians, analytics platforms, and scheduling tools. Pacific Blue Engineering describes PLCs as the layer that connects plant hardware to business systems, and that matches what I see in the field: when PLC systems are designed well, they become the backbone that supports quality, energy efficiency, and uptime. When they are neglected, production turns into a sequence of workarounds and manual interventions.

Chemical plants also face a widening digitalization gap. The Texas Chemistry Council notes that many facilities still rely on paper instructions and spreadsheets even while their process control systems generate huge volumes of data. Meanwhile, AspenTech case studies show that advanced scheduling, tightly integrated with plant data, can raise on-time, in-full delivery, cut inventories by roughly a quarter across multiple sites, and reduce logistics costs by millions of dollars per year. None of that works reliably unless the underlying PLC and control infrastructure is stable, well-powered, and instrumented for data.

As a power system specialist, I treat PLCs and their supporting power systems as one problem. You cannot ask a controller to deliver high-integrity, 24/7 control if it is tied to noisy feeders, under-sized UPS systems, or inconsistent grounding. In chemical plants, that is not just a reliability issue; it is a safety and compliance risk.

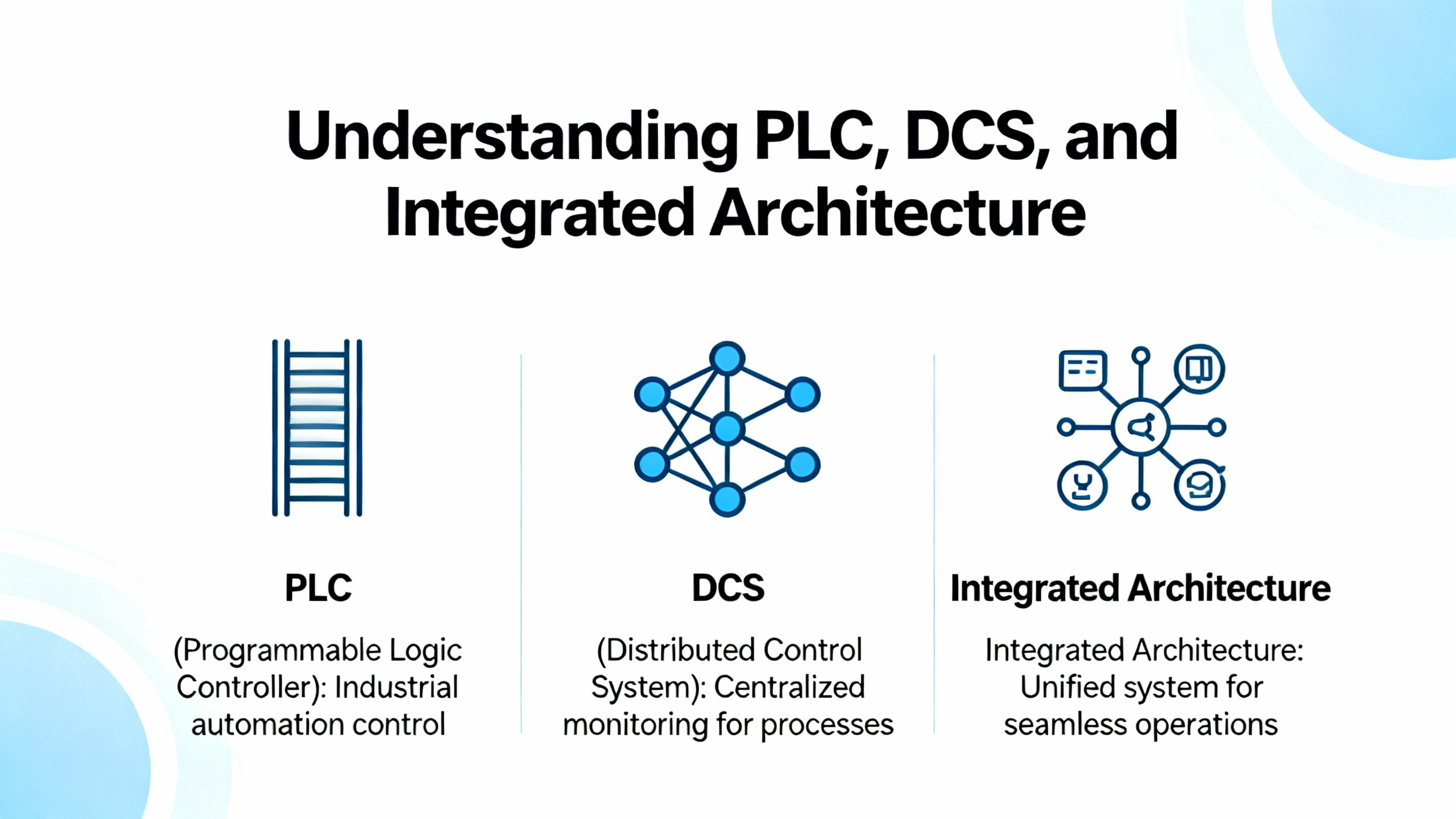

A long-running discussion in the control engineering community asks whether a distributed control system (DCS) or a PLC plus SCADA architecture is ŌĆ£bestŌĆØ for a small or medium plant. Contributors on the Control.com forum make an important point: there is no generic answer. The right choice depends on process complexity, advanced control needs, lifecycle strategy, and internal capabilities.

Experienced practitioners recommend starting with engineering, not vendor brochures. That means simulating the process with tools such as dynamic process simulators, designing the control strategy loop by loop, and then turning that into a detailed specification of what the control platform must do. That specification should cover basic regulatory loops, advanced control, alarm management, asset management, and operator support tools. Only then does it make sense to score different PLC, SCADA, or DCS platforms against those requirements.

Rockwell Automation pushes the discussion one step further by arguing that the real problem is not PLC versus DCS but fragmented architectures. Their guidance for chemical plants stresses that basic process control, safety systems, drives, motor control centers, instrumentation, energy management, and power systems should not live on islands. A single integrated platform, sometimes marketed as a ŌĆ£total connected chemical plant,ŌĆØ lets you share data and apply consistent security and lifecycle practices across the enterprise.

A practical way to think about the choice is summarized below. This table does not dictate an answer but helps frame the tradeoffs using themes echoed by Control.com, Rockwell Automation, and integrators such as JHFoster.

| Architecture type | Typical strengths | Typical challenges | When it fits best |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLC plus SCADA | Flexible, modular, often lower initial cost; easy to expand skid by skid; good for discrete and hybrid processes | Risk of ŌĆ£islands of automationŌĆØ if each PLC is treated separately; integration effort shifts to the project team | Plants with many packaged units, brownfield upgrades, or mixed vendors where modular growth is expected |

| Classic DCS | Strong native support for continuous process control, historian, and advanced control; integrated engineering tools | Higher vendor lock-in and upfront cost; less flexible for small stand-alone systems | Large, continuous processes with many tightly coupled loops and high regulatory burden |

| Integrated single platform (hybrid DCS/PLC) | One engineering environment for process, safety, power, and drives; unified security and diagnostics; easier enterprise integration | Requires careful front-end engineering to avoid over-customization; modernization of legacy assets can take time | Plants aiming for long-term digitalization, predictive maintenance, and integrated safety and energy management |

The JHFoster bakery case, where PLCs from thirty-five different equipment suppliers were unified under a single SCADA platform that interfaced directly with the enterprise resource planning system, shows what is at stake. Once the data from all those PLCs lived in one coherent environment, the facility gained recipe management, plant-wide alarming, and real-time production tracking. Chemical plants can achieve similar gains when they eliminate islands of automation and standardize how PLCs present data upward.

From a power systems perspective, integrated architectures also change how you design the electrical backbone. Instead of treating each PLC panel as a stand-alone load, you design coordinated power and protection for the entire control domain: dedicated feeders, properly rated transformers, coordination of protective devices, clean grounding, and UPS systems sized for the combined control, networking, and safety workloads.

Troubleshooting guides from DoSupply and Polsys repeatedly show that low or unstable voltage, poor grounding, noise from large motors or welding equipment, and battery failures are major contributors to PLC faults and corrupted memory. If control power is taken from convenience panels or overloaded panels, you will see more intermittent faults and ŌĆ£mysteryŌĆØ CPU resets. In chemical plants where the control system sits between you and an environmental incident, dedicating high-quality power infrastructure and industrial-grade UPS systems to PLCs, HMIs, and network switches is not a luxury. It is an essential layer of risk reduction.

MinitabŌĆÖs guidance on chemical manufacturing quality is blunt: you cannot improve what you do not measure in real time. They recommend PLC-based automated data collection, traceable specification plans, and real-time dashboards to detect out-of-spec raw materials and finished products. When PLCs stream temperature, pressure, flow, and composition values to a historian, engineers can run control charts, capability studies, and stability analyses that reveal whether a process is genuinely capable of meeting customer requirements.

The Texas Chemistry Council points out that while control systems already collect huge amounts of data, traditional monitoring and alarm panels do not automatically turn that data into insight. That is where integrations with advanced analytics, whether from Minitab-style statistical packages, AspenTech scheduling tools, or specialized manufacturing analytics, become powerful. For complex batch processes, ŌĆ£golden batchŌĆØ analysis compares each run against a best-performing reference. Deviations in a PLC-controlled temperature ramp or agitation speed can then be linked directly to yield or quality losses.

In practice, this means that when you design PLC applications for a reactor, distillation column, or blending line, you should think beyond setpoint tracking. Ensure that all critical parameters and setpoints are logged with enough resolution and metadata to support later statistical work. For example, if a controllerŌĆÖs range is from minus fifty to plus fifty degrees Fahrenheit, as described in AIChE discussions of control-loop performance analysis, logging both the setpoint and process value allows you to compute normalized error and determine whether tuning changes actually reduce variability.

Safety and environmental performance rely on continuous monitoring and rapid, reliable intervention. Minitab emphasizes that emissions data should be analyzed statistically to demonstrate compliance and to predict the impact of process changes before implementation. The Texas Chemistry Council reinforces that chemical manufacturing is among the most regulated manufacturing sectors in the United States, with reporting thresholds based on production volumes and strict expectations for traceable, tamper-resistant records.

A PLC-centric system supports this in three ways. First, it maintains tight regulatory control, often through cascaded loops and interlocks that drive the process toward safe operating targets. Second, it feeds alarm systems that have been rationalized so that operators see only relevant, actionable alarms rather than floods of chattering or stale alerts. Third, it records the sequence of events: which interlock tripped, which valve moved, and which setpoint changed, all time-stamped for later analysis and for regulatory audits.

Texas Chemistry Council case material stresses that alarm rationalization and better HMIs can dramatically improve operator productivity by removing distracting ŌĆ£bad actorŌĆØ alarms. Pacific Blue EngineeringŌĆÖs work on HMI design for PLC systems adds another layer: intuitive navigation, clear status indication, and fault messages that guide operators through corrective actions. When you combine better alarms with operator interfaces designed around real decision-making, you reduce the need for manual loop manipulation during upsets, which is exactly what AIChE cautions against in their analysis of control loop misuse.

Consider a batch reactor with a history of borderline quality. A PLC controls jacket temperature, feed flows, and agitation speed. By integrating that PLC with a historian and applying the AIChE-style performance metrics, you might find that the temperature loop spends only half of its time in automatic mode, with operators frequently changing setpoints to ŌĆ£help.ŌĆØ The service factor would be about fifty percent, which AIChE classifies as non-optimal.

Once that is visible, engineers can retune the controller, fix valve stiction if needed, and redesign interlocks so operators feel comfortable keeping the loop in automatic mode. In parallel, process engineers can use MinitabŌĆÖs design of experiments to optimize the temperature profile or feed strategy. Over time, you move from reactive, manual control to stable, automated operation with documented process capability.

Several independent sources converge on the same observation: once a PLC system has been properly wired and programmed, most of the problems that appear later are not CPU failures. DoSupply notes that more than eighty percent of issues in previously working systems arise from I/O modules, wiring, and field devices rather than the processor. Polsys adds that environmental stresses such as heat, dust, and vibration, plus human errors and neglected maintenance, are common contributors to faults.

As a reliability advisor, I see another pattern layered on top of that: many of the remaining ŌĆ£mysteryŌĆØ faults trace back to marginal power quality. Loose neutral or ground connections, long runs feeding both control and heavy drives, inadequate surge protection, and aging UPS batteries show up as intermittent CPU resets, corrupted memory, or unexplained I/O dropouts. Combining the field experience in these troubleshooting guides with secure PLC coding practices from industrial cybersecurity initiatives highlights an important lesson. PLC reliability is the sum of good power, robust hardware, disciplined coding, and structured troubleshooting.

RealPars and Matthews Industrial Solutions both advocate a basic methodology that aligns well with vendor-agnostic flowcharts from DoSupply. The sequence begins with understanding the problem from operators and reviewing data trends. Then it moves through the system in a logical order:

First, confirm that power is healthy. That means checking that control transformers, power supplies, and UPS outputs provide stable voltage within specification; verifying that fuses and breakers are intact; and ensuring that the emergency stop circuit is not engaged. DoSupply stresses that unstable or noisy power is a root cause of many internal PLC faults, and Polsys recommends using power analyzers and multimeters to validate conditions rather than relying on assumptions.

Second, read the PLC and I/O status indicators. CPU LEDs often differentiate between general faults, alarms related to program execution, and low battery conditions that could threaten RAM-based programs. I/O module LEDs show whether modules have power and whether individual channels are active. While these indicators are only first-level diagnostics, they quickly reveal whether you are dealing with an internal PLC issue or a problem in the field.

Third, validate the software layer. Comparing the running program to the known-good master copy protects against corruption or accidental edits. If the two differ, reload and retest. Both DoSupply and Polsys emphasize the importance of maintaining up-to-date backups and documenting every change. On the logic side, RealPars recommends using vendor debugging tools and, when needed, reviewing functional design specifications to make sure the program still reflects the original intent.

Fourth, work outward into field I/O and the environment. Faulty sensors, actuators, cabling, or network equipment often masquerade as ŌĆ£PLC problems.ŌĆØ DoSupplyŌĆÖs advice is to focus first on outputs and their circuits, which are statistically more likely to fail than inputs, and to note how normal LED patterns look so that deviations are easier to spot. At the same time, Polsys encourages checking enclosure cleanliness, cooling fans, and mounting conditions, because environmental degradation is slow and easy to overlook.

Only when power, program, I/O modules, field devices, and environment have been cleared does it make sense to treat the CPU itself as the likely culprit and consider replacement. That disciplined hierarchy keeps downtime and spare-parts spending under control.

AIChEŌĆÖs guidance on troubleshooting control loops provides a statistical lens to complement traditional troubleshooting. Rather than relying only on anecdotal complaints, you can export one-minute data for a week from your DCS or SCADA system and compute three simple metrics for each controller:

The first is service factor: the fraction of time the controller is actually in automatic mode and not in manual, tracking, or conditional status. AIChE suggests that service factors below fifty percent are poor and above ninety percent are good.

The second is the normalized standard deviation of the control error, defined as the standard deviation of setpoint minus process value divided by the controller range. Higher values indicate ŌĆ£noisierŌĆØ control and help prioritize tuning and hardware work.

The third is setpoint variance, which highlights loops where operators frequently move the setpoint in response to disturbances. High normalized setpoint variance often signals controllers that are poorly tuned or mistrusted by operators.

In a mid-size plant, simply ranking loops by service factor and normalized error can surface a shortlist of bad actors where a few days of focused tuning, instrumentation checks, and, in some cases, adaptive tuning will yield outsized benefits. That is a far more efficient approach than trying to ŌĆ£fix everythingŌĆØ at once.

The Top 20 Secure PLC Coding Practices project, described by Industrial Cyber, argues that on real-world PLCs today, integrity matters more than confidentiality. Their guidance breaks PLC-specific security into integrity of logic, integrity of variables and I/O, monitoring, hardening, and resilience.

For logic integrity, they recommend modular code structures and, where feasible, checksum or cryptographic checks to detect unauthorized changes. For variable and I/O integrity, they suggest treating external inputs as untrusted. That includes validating timers and counters, range-checking HMI entries, using paired inputs or plausibility checks where possible, and assigning register blocks by function to make inappropriate writes more obvious.

This mindset aligns with the safety culture in chemical plants. You should assume that anything entering the PLC from outside can be wrong, noisy, or malicious. Control logic should validate critical values before acting, and additional instrumentation should be used where necessary to cross-check measurements that, if wrong, could lead to unsafe states.

The same Top 20 initiative emphasizes PLC-specific monitoring such as scan cycle times, uptime, hard stops, and memory use, because these metrics often signal both cyber and reliability issues. On the hardening side, restricting communication ports and protocols and minimizing unnecessary third-party interfaces are practical steps that most current PLCs can support.

There are limits. Many installed PLCs do not offer strong authentication or modern cryptography, which means that secure coding and network design must work around those constraints. The project explicitly notes that it does not solve ŌĆ£insecure by designŌĆØ issues such as unauthenticated but legitimate features abused by advanced attackers. Those gaps require better PLC product design and broader OT security programs.

For chemical plants, resilience is especially important. Controllers must define safe states for restarts and failures, and power systems must be designed so that brief electrical disturbances do not repeatedly bounce controllers offline. From a power-protection standpoint, that means pairing robust PLC coding with UPS systems that can ride through short outages, voltage sags, and utility switching events, while ensuring that emergency shutdown systems behave deterministically even under degraded conditions.

Advanced control techniques such as model predictive control and adaptive control are increasingly used in chemical plants to manage complex reactions and multivariable interactions. FAT FINGERŌĆÖs overview of process optimization highlights how real-time monitoring, predictive control, and adaptive systems allow plants to maintain optimal reaction conditions, cut waste, and improve safety. Those capabilities depend on reliable PLC data and well-instrumented processes.

Platforms like FAT FINGER also illustrate how digital tools can turn raw PLC data into usable workflows. Operators can enter supplemental data from cell phones or tablets, follow digitized standard operating procedures, and receive automated alerts when process parameters drift. That bridges a gap identified by the Texas Chemistry Council, where many plants have sophisticated controls but still rely on manual, paper-based reporting and problem solving.

At the planning layer, AspenTech documents how advanced production scheduling tied into plant data can greatly improve on-time, in-full performance, reduce inventories by about twenty-five percent across multiple sites, cut freight costs by millions of dollars annually, and even shorten supply lead times by roughly ten days in some cases. These results show how tightly coordinated plans and plant-floor execution can impact both revenue and working capital.

A ScienceDirect case study of the ALTAIR chemical plant describes an Industry 4.0 approach where an optimized production planner generates several possible two-day plans using detailed models and a mix of DCS and SCADA data. The system ingests plant status, orders, energy prices, and production parameters via an IoT architecture based on technologies such as OPC-UA gateways, an IoT broker, and cloud-hosted microservices. It stores both real-time DCS measurements and planned trajectories under a common data model so operators can compare planned versus actual tonnage and conditions one-to-one.

Although the technology stack is different from classic PLC and SCADA alone, the principle is the same: high-quality, time-synchronized PLC and DCS data make it possible to optimize production schedules against constraints like storage capacity, shipment windows, and energy tariffs. That integration is only robust if the underlying PLC systems are reliable, secure, and properly powered.

Chemical companies rarely get the chance to rebuild their control systems from scratch. Most upgrades are incremental, mixing new PLCs with legacy systems. The most successful projects I see follow a pattern that echoes the recommendations from Control.com, JHFoster, Rockwell Automation, AIChE, and Texas Chemistry Council sources.

They begin with front-end engineering. Process simulations and control narratives define how each unit should behave, including normal operations, startups, shutdowns, and abnormal situations. That model becomes the basis for a requirement-driven platform selection: whether to favor a PLC plus SCADA solution, a DCS, or a hybrid integrated architecture.

Next, the project team defines the integration and data strategy. JHFosterŌĆÖs work shows the value of setting standards for PLC-to-SCADA interfaces and building templates that can be reused as new equipment is added. Texas Chemistry Council material suggests thinking at the same time about how PLC data will feed advanced analytics, golden batch tools, maintenance systems, and regulatory reporting, not just HMIs.

In parallel, power and network reliability are engineered deliberately. Drawing on the troubleshooting experience reported by DoSupply, Polsys, and others, that means designing dedicated control power with appropriate UPS topologies, surge protection, grounding, and environmental controls in every PLC room. On the networking side, it means segmenting control networks, securing remote access as described by Pacific Blue Engineering, and implementing PLC coding practices that validate inputs and maintain safe states.

Commissioning is planned collaboratively, as JHFoster recommends, with plant owners, system integrators, and end users agreeing on functional tests, performance criteria, and documentation standards. Post-startup, AIChE-style control loop metrics and MinitabŌĆÖs statistical tools are used to monitor performance, while scheduling and planning tools such as those from AspenTech or custom Industry 4.0 implementations leverage the newly available data to optimize operations.

Throughout the lifecycle, structured troubleshooting and disciplined change management keep the PLC systems reliable. Regularly reviewing control-loop service factors, updating firmware and software with an eye on compatibility, and periodically testing UPS and power protection systems ensure that the automation layer and the power layer age gracefully together, rather than undermining each other.

For chemical manufacturers, PLC systems are no longer just about flipping outputs in the right sequence. They are the foundation on which quality, safety, digital reporting, and even production scheduling now rest. When you treat PLC architecture, power quality, cybersecurity, and analytics as one integrated reliability problem, your plant stops reacting to disturbances and starts absorbing them. That is the kind of resilience a modern chemical operation needs if it wants to stay in control and stay competitive.

How should a chemical plant choose between PLC plus SCADA and a DCS? Control engineers on forums such as Control.com recommend starting with a detailed engineering specification based on simulations and control narratives rather than on technology labels. For smaller or more modular plants with many packaged units, PLC plus SCADA can offer flexibility and lower incremental cost, provided you avoid islands of automation. For tightly integrated, continuous processes with heavy regulatory and advanced control needs, a DCS or an integrated hybrid platform may fit better. The key is to evaluate platforms against a checklist of functional and lifecycle requirements, not brand preferences.

What is the single most overlooked factor in PLC reliability in chemical plants? Field experience and troubleshooting guides from DoSupply and Polsys suggest that power quality and grounding are often underestimated. Many ŌĆ£PLC problemsŌĆØ ultimately trace back to marginal control power, insufficient surge protection, and aging UPS batteries, especially when control power shares feeders with large motors or welding equipment. Designing dedicated, well-protected power for PLCs, HMIs, and networks is one of the most cost-effective reliability upgrades you can make.

How can a plant start using PLC data for optimization without a full Industry 4.0 overhaul? You do not need a full IoT stack on day one. Minitab and the Texas Chemistry Council both argue that simply connecting existing PLCs to a historian and using basic statistical tools for control charts, capability analysis, and alarm rationalization can deliver measurable benefits. As confidence grows, you can add digital workflows such as FAT FINGER-style mobile data collection or AspenTech-like advanced scheduling. The important step is to standardize how PLCs expose data and to insist that new projects follow the same conventions, so your analytics capabilities can grow steadily over time.

Leave Your Comment