-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In industrial and commercial power supply systems, programmable logic controllers sit between the electrical reality of breakers, UPS modules, inverters, and transfer switches, and the business reality of uptime and safety. A PLC is, as described in several vendor guides, an industrial digital computer that continually reads inputs, executes a user program, and drives outputs in a millisecond-scale scan cycle. It has been the backbone of automation for decades in everything from conveyor systems to refinery units and power distribution panels.

In power protection environments, that scan loop is orchestrating very practical decisions: when to start a backup source, when to open or close a breaker, when to alarm on overtemperature, or how to sequence the start-up of several power supplies. A mis-specified PLC here is not just an engineering inconvenience. As the Digi-Key technical team notes, downtime often costs hundreds or even thousands of dollars per minute once you account for idle labor, scrap, overtime, and lost customer goodwill. Because PLC platforms often remain in place for decades, the selection you make for a UPS or inverter plant today will shape your ability to maintain and expand that system for a very long time.

This guide approaches PLC selection from a power system specialist and reliability perspective, drawing on practical recommendations from Maple Systems, Industrial Automation Co., R.L. Consulting, Simcona, c3controls, and others, as well as safety PLC guidance from a ForumAutomation safety discussion and soft-requirement insights summarized by Digi-Key. The focus is on turning those recommendations into concrete criteria and examples that apply directly to industrial and commercial power supply systems.

Several authors emphasize that PLC selection should start from your process, not from a catalog page. R.L. Consulting suggests defining application scope, control complexity, and environment first. ACE points out that process applications are dominated by analog input and control, governed by PID algorithms, while discrete applications are dominated by simple on or off logic.

Power supply systems usually mix both. Analog behavior shows up in DC bus voltage, current, temperature, and sometimes power factor or harmonic distortion readings, while discrete behavior shows up as breaker status contacts, UPS alarm relays, transfer switch position indications, and interlock chains. ACE describes process applications such as refineries and water treatment, which rely on continuous signals, but notes that many real systems are hybrids. A power room feeding critical data center loads is typically a hybrid as well: you might have analog monitoring for bus temperatures and battery strings, and discrete interlocks for permissives and trip circuits.

The first practical step is therefore to map your power process the same way you would a process plant. Make a schematic that identifies each sensor and actuator, and note whether it is essentially analog or discrete. Simcona recommends starting from a process or equipment schematic for this reason, since it forces you to confront I/O counts and device locations early rather than discovering them after you have chosen a PLC family.

Digi-KeyŌĆÖs discussion of soft requirements highlights that many people will touch your PLC over its decades-long life: system integrators, commissioning engineers, technicians, and future staff who will add features or troubleshoot failures. Their key point is that lifecycle and supportability usually dwarf the initial PLC purchase price. If your UPS-backed switchboard feeds production lines where a single minute of lost power can scrap product or halt an entire facility, that cost per minute of downtime referenced by Digi-Key is very real. In such situations, you should bias decisions toward reliability, diagnostics, and ease of maintenance rather than minimal acquisition cost.

They also note that PLC platforms often remain available and supported long after sales stop. The Rockwell SLC 500 family, for example, was introduced over thirty years ago and discontinued about ten years ago, yet Digi-KeyŌĆÖs summary points out that specific modules are still commonly found in the aftermarket. That longevity is typical of industrial PLC ecosystems and is one reason many plants standardize on a small number of brands.

In a power system context, this means your PLC choice should factor in not only current functionality but also whether your maintenance team will still be able to find trained people, spare modules, and support tools fifteen or twenty years from now. For critical UPS and inverter plants, this often supports choosing an established platform with strong training and documentation rather than a short-lived niche controller.

Consider a medium-size commercial building with two UPS modules, an automatic transfer switch, and several downstream power panels feeding critical IT and HVAC loads. Before ever naming a PLC brand, you would map out:

The number of discrete status points you need, such as breaker open or closed feedbacks, ATS position, UPS alarm relays, and local permissive pushbuttons.

The number of analog variables that matter, such as DC bus voltage, inverter load percentage, transformer temperatures, and room temperature if you want to link control to cooling.

The expected duty and environment, including whether the PLC will live in a conditioned electrical room or near transformers that run closer to the typical 32 to 130 ┬░F range that Simcona associates with rugged PLC operation.

From that sketch, you already get a sense of whether your application behaves like a small, discrete machine, a largely analog process, or a hybrid, and what criticality level applies if anything goes wrong.

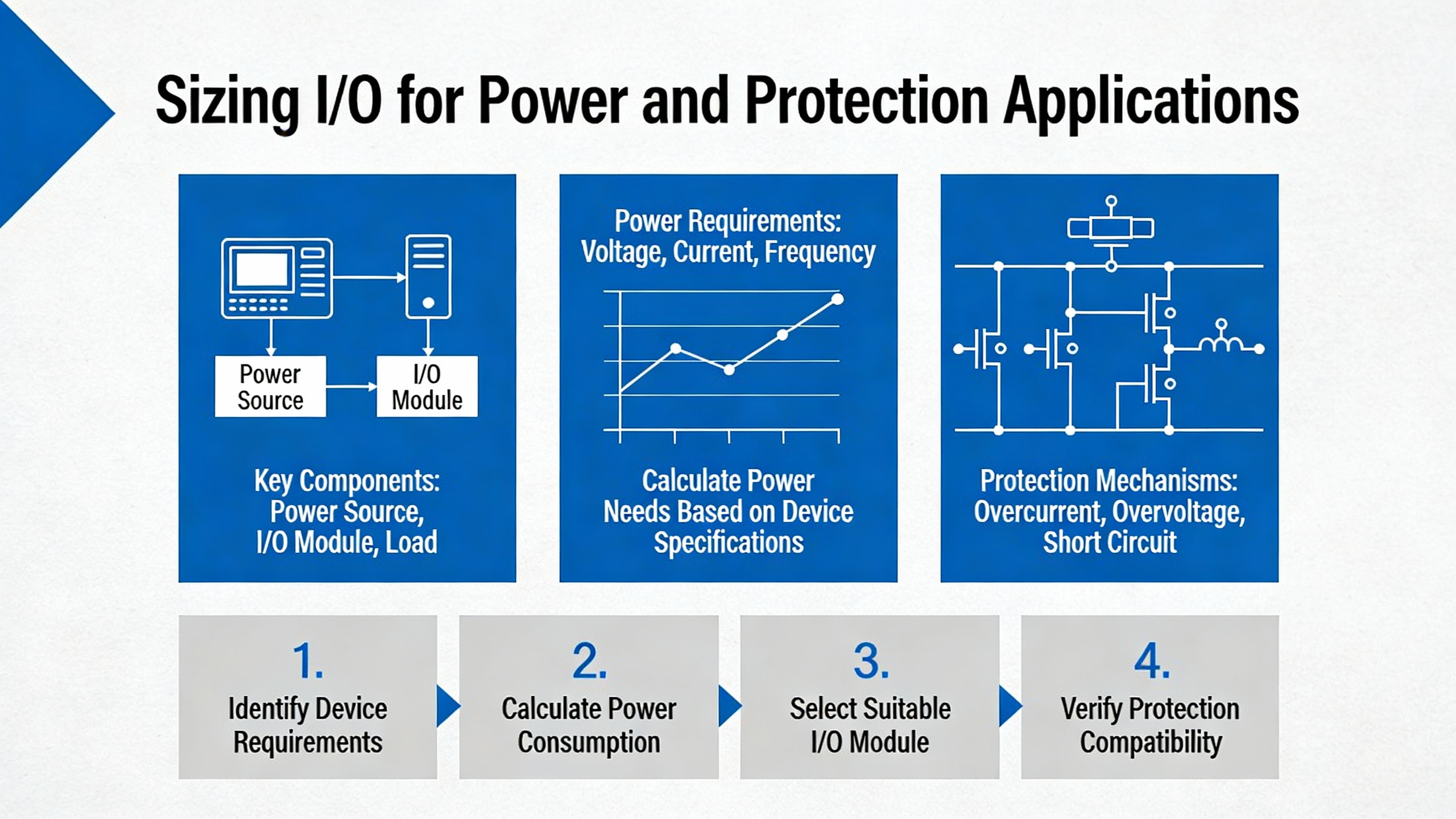

All the major references agree that I/O sizing is one of the most critical steps. Industrial Automation Co. stresses that your estimate of the number and types of I/O points should include both current needs and near-term expansion, while Maple Systems goes into detail on the types of I/O you should consider.

Digital I/O is used for on or off sensors and actuators. In a power room, those are things like auxiliary contacts on breakers, dry contacts on protective relays or UPS units, door switches, and relay coil outputs to trip or close a device. Maple describes digital inputs as sensors with on or off states, and digital outputs as devices such as relays or contactors.

Analog I/O handles continuous values such as temperature, pressure, or level. ACE notes that process applications lean heavily on analog I/O and gives examples like pressure, level, and flow. In a UPS or inverter plant, that maps well to bus voltage, current, battery temperature, or cooling water flow where applicable. Maple and ACE both emphasize common analog signal formats such as 4 to 20 mA, 0 to 5 VDC, ┬▒5 VDC, and 0 to 10 VDC, along with specialized modules for thermocouples and RTDs. If you are monitoring transformer or bearing temperatures, you will often be in those categories.

Specialty I/O includes high-speed counters and pulse-width modulation outputs. Maple highlights high-speed count inputs for precise counting of fast processes and PWM outputs for speed or position control of servo devices. In many power applications these are less common, but they may appear in auxiliary systems such as cooling fans or motorized breakers where you need pulse control.

Safety I/O is its own category. The ForumAutomation safety PLC overview notes that safety PLCs often use dedicated safety-rated inputs and outputs to implement safety-related functions in compliance with standards such as IEC 61508 and IEC 61511. If your power system includes safety functions that shut down equipment to protect people or the environment, you may need safety-certified I/O rather than standard modules.

A real-world forum example summarized in the research notes describes an engineer replacing a relay-based control system with a PLC. Their system switched and monitored power supplies with simple logic and had about forty-six digital inputs, forty-five digital outputs, twelve analog inputs, and twelve analog outputs. The existing hardware occupied a six-unit high, nineteen inch rack enclosure, and all I/O came through eight D-sub connectors. The engineer wanted to keep everything in the same enclosure, avoid distributed I/O, and replace a front panel of illuminated pushbuttons with an HMI.

If you translate that example into the power protection domain, the numbers are very representative of a modest UPS and distribution panel: dozens of status contacts and control outputs, and a dozen or so analog measurements. Using the guidance from Industrial Automation Co. and Maple Systems, you would look for a modular PLC whose base rack or backplane can accept this number of digital and analog channels, plus at least twenty to thirty percent headroom for future expansion. Since the engineer wanted a centralized arrangement within the same nineteen inch rack, a modular or rack-mount PLC with I/O cards instead of separate distributed modules would fit the form factor and connection style.

The presence of twelve analog outputs hints at control functions, perhaps for setpoints or references to power electronic equipment. That reinforces the need to check that your chosen PLC family has analog output capabilities in the right ranges, not just analog inputs, and supports any required scaling or signal conditioning in software.

When the power system includes safety-related functions, such as safely shutting down a generator in case of overspeed or ensuring that a bus transfer cannot create a dangerous backfeed, a safety PLC may be required. The safety PLC guidance summarized from ForumAutomation explains that safety PLCs are purpose-built to execute safety-related functions to protect people, machinery, and the environment, and are designed to meet Safety Integrity Level requirements from SIL1 to SIL3.

If your risk assessment or standard requires SIL2 or SIL3 protection for a particular function, the safety PLC you select must have third-party certification, for example from TÜV or UL, confirming compliance with relevant functional safety standards. The same source emphasizes redundancy options such as redundant power supplies, CPUs, I/O modules, and network paths, along with built-in self-diagnostics and watchdog timers. It also stresses the need for clear failsafe behavior so that upon fault detection, the system moves to a defined safe state, such as de-energizing selected outputs.

In a power distribution or UPS system, that might mean that on detection of a critical internal PLC fault, outputs associated with nonessential loads drop out while critical feeder protection relays retain power, or that transfer commands are inhibited. The specifics come from your safety design, but the PLC platform must technically support the required SIL level, safety I/O, diagnostics, and safe-state configuration.

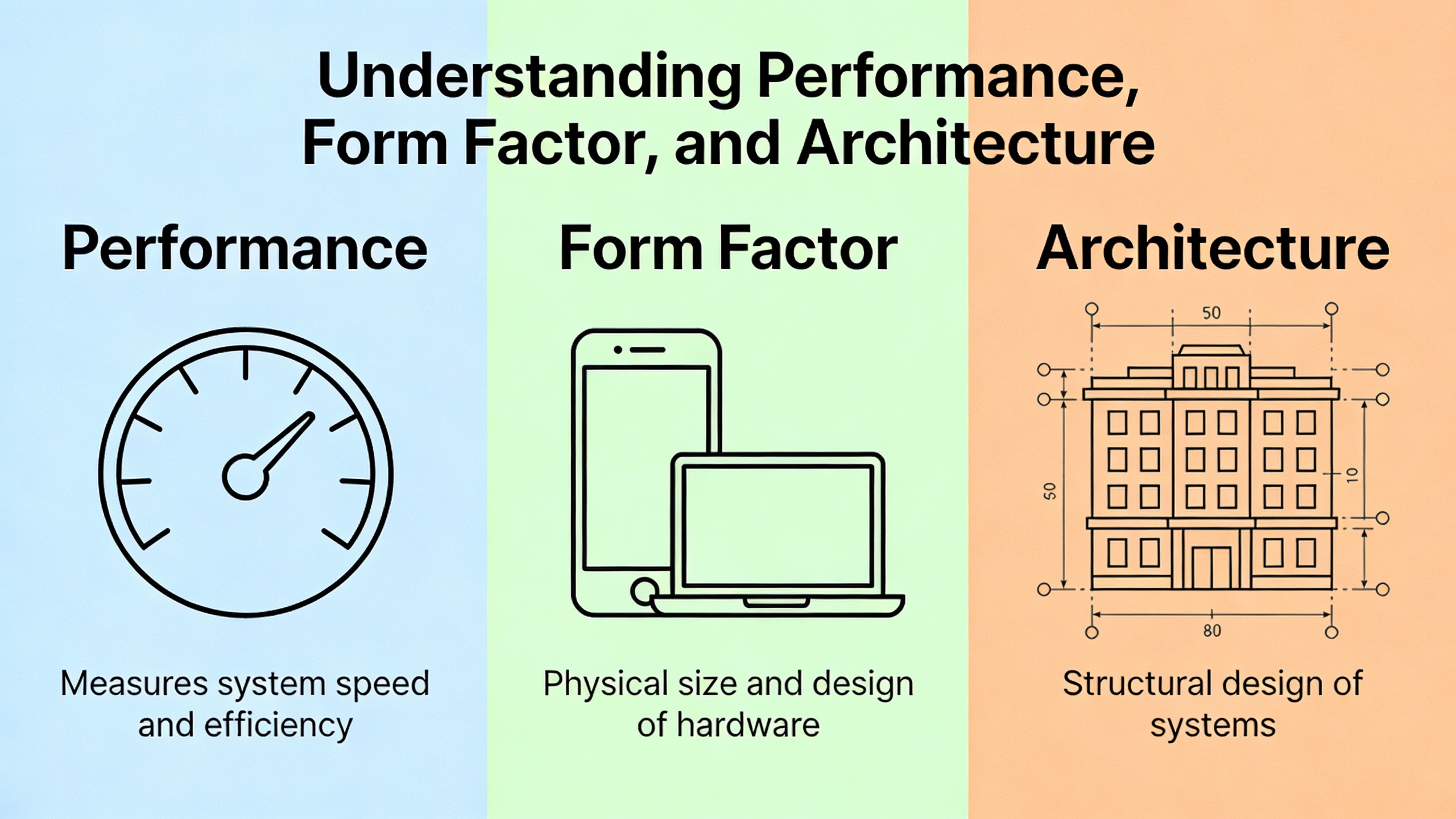

Industrial Automation Co., Maple Systems, and R.L. Consulting all flag CPU performance and memory size as core selection parameters. Maple describes the CPU as the heart of the PLC and notes that CPU speed in megahertz or gigahertz and architecture, for example thirty-two or sixty-four bit, determine how quickly the controller can execute complex, high-speed tasks. They explain that program memory stores the control logic while data memory holds process variables, and that larger systems with more complex operations require more memory.

For power systems, CPU load comes from logic sequences, data logging, alarm management, communications, and sometimes embedded control algorithms such as PID loops for cooling or voltage regulation. R.L. Consulting stresses that you should ensure sufficient processing power and fast response time for real-time or high-speed manufacturing, and the same logic applies to fast electrical events such as transfer switch commands or breaker trip indications.

Scan time connects performance directly to plant behavior. Maple defines scan time as the time for the PLC to read inputs, execute the program, and update outputs, typically in milliseconds, and notes that shorter scan times improve responsiveness in high-speed or time-sensitive processes. If your UPS control design requires that the PLC recognize a loss of input and command a transfer sequence within a tight time window, you want a PLC and code structure that keep scan time well below that response requirement, and you want to avoid bloating the program with low-value background tasks that slow the scan.

As an example, imagine a PLC controlling a static transfer between two sources feeding critical loads. If your control philosophy demands that, after a trigger, transfer logic evaluate permissives and issue a command within a small fraction of the time it would take protective relays to act, you would favor a PLC configuration whose measured scan time remains comfortably shorter than that permissible window even after you add future features such as data logging or remote communications.

Form factor and architecture must match both your present and future needs. Industrial Automation Co. and Maple Systems outline three broad categories. Compact or fixed PLCs integrate the CPU, I/O, and communication interfaces into a single unit. Maple notes that they are typically more compact but offer less flexibility for future expansion and are best suited to small systems with defined and stable requirements.

Modular PLCs separate the CPU, power supply, and I/O into individual modules that plug into a backplane, allowing you to add or remove I/O and specialty cards. Maple describes modular or expandable PLCs as flexible and future-proof because you can evolve them with changing needs without a full system replacement. Industrial Automation Co. points out that modular PLCs are a good fit for medium to large systems and for applications that may need extra communication interfaces later.

Rack-mount PLCs, as summarized by Industrial Automation Co., target large, complex plants needing high processing power and extensive networking. These systems are common in large process units, but the same architecture can be appropriate for very large power plants or campus-scale distribution systems.

A simple way to visualize the trade-offs in the power supply context is summarized here.

| PLC type | Typical use in power systems | Main strengths | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compact / fixed | Small panels, single UPS or small transfer switch board | Small footprint, lower upfront cost, simplicity | Limited I/O and communication expansion |

| Modular | Multi-UPS plants, power rooms with several panels | Flexible I/O, add specialty and network modules | Requires more panel space and more detailed design |

| Rack-mount | Large plants, integrated power and process control | High capacity, extensive networking possibilities | Higher cost and complexity, usually overkill for small jobs |

This table is adapted from the form-factor descriptions in the Maple Systems and Industrial Automation Co. guides and translated into power system contexts. When in doubt for a new or evolving power room, a modular PLC usually offers the best compromise between flexibility and complexity.

The forum retrofit example mentioned earlier involved a strong preference to avoid distributed I/O and keep everything in a single enclosure. There are valid reasons for that preference: centralized I/O simplifies documentation, parts stocking, and often troubleshooting. However, Simcona and R.L. Consulting both point out that the mix of local versus remote I/O is a key consideration. Remote I/O can drastically shorten field wiring runs when equipment is physically scattered, and it can simplify future expansion because you can add a remote rack near new equipment instead of pulling long new cable bundles back to a central panel.

In a power distribution setting where all critical devices live in the same room or lineup, a centralized modular PLC, like the one sought in the forum example, is often practical. In campuses or facilities where switchgear and UPS rooms are separated by long distances, using remote I/O drops connected via Ethernet-based protocols such as PROFINET, Modbus TCP, or Ethernet/IP, as described by Industrial Automation Co., ACE, and c3controls, can reduce cable costs and noise susceptibility. The choice should reflect your physical layout and maintenance philosophy rather than a blanket rule.

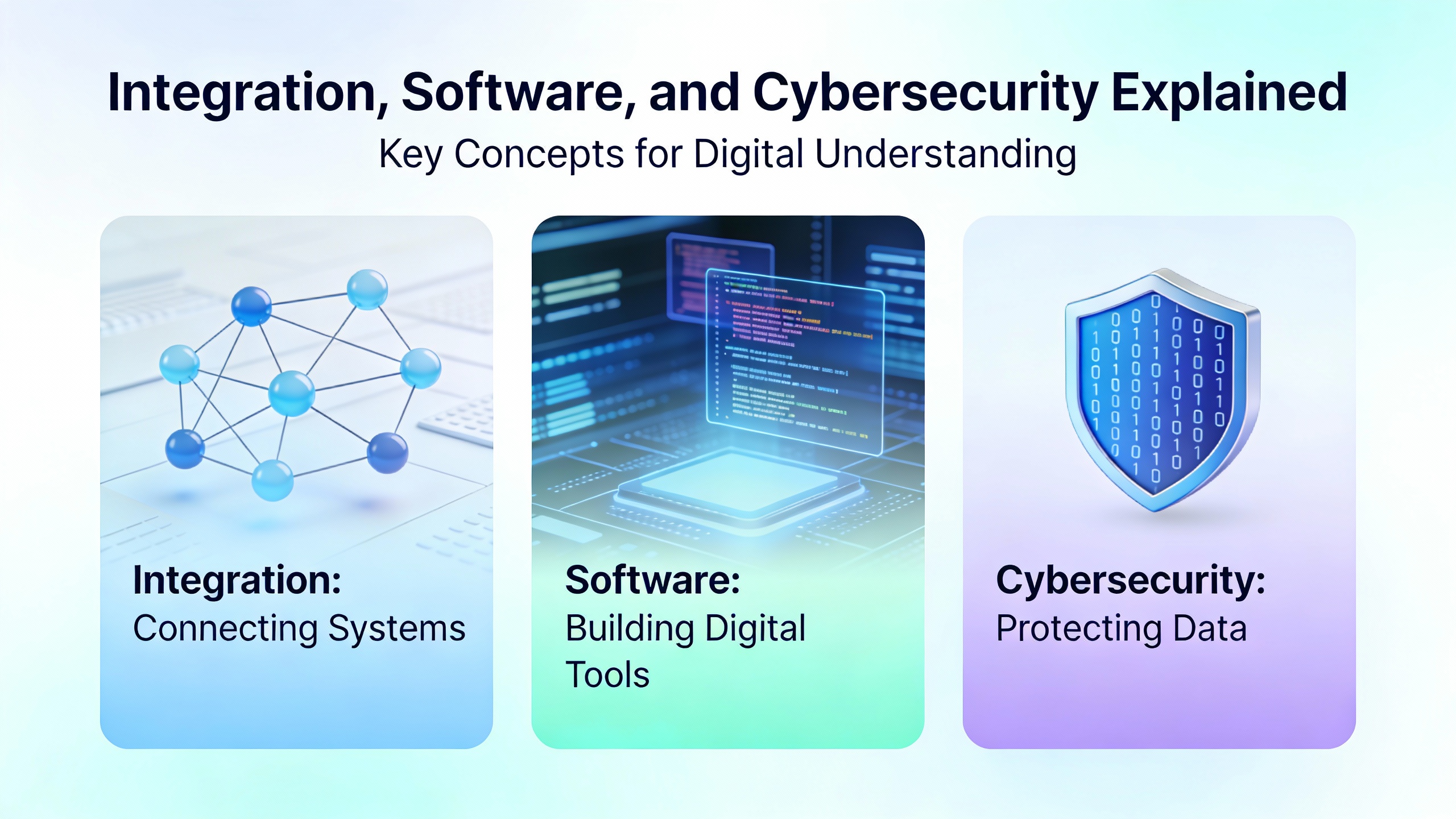

Connectivity determines how your PLC will talk to UPS modules, meters, building management systems, and supervisory SCADA. Industrial Automation Co. lists Ethernet/IP, PROFINET, and Modbus as common industrial protocols. RL Consulting mentions Ethernet-based protocols and Modbus as key for integrating with SCADA, HMIs, remote I/O, and other devices. ACE notes that many modern PLCs support fieldbus communication such as Ethernet/IP, Modbus TCP, and PROFINET natively or via expansion cards.

Maple Systems emphasizes the importance of evaluating available Ethernet, serial RS-232 or RS-485, and USB ports to match system connectivity needs. c3controls notes that modern PLCs usually support multiple industrial networks to integrate with SCADA, MES, and ERP systems.

For a power supply system, it is common to combine serial links to legacy devices, Ethernet for modern intelligent electronic devices, and one or more Ethernet-based plant networks for SCADA or energy management. The key selection question is whether your chosen PLC family supports the exact mix of networks you need today and can add more interfaces later without replacing the CPU. This is especially important when you anticipate integrating Industrial Internet of Things or analytics platforms later, something R.L. Consulting calls out as part of future-proofing.

Maple Systems, Industrial Automation Co., and Digi-Key all stress that programming language support and staff skills are critical. Under the IEC 61131-3 standard summarized by c3controls and Maple, PLCs support several principal languages, each with strengths.

Ladder Diagram resembles relay logic diagrams and is especially intuitive for technicians with electrical backgrounds. Maple notes that it excels in simple control systems and binary decisions. Instruction List is a low-level, compact textual language but is less intuitive, and some standards consider it deprecated. Function Block Diagram represents functions as blocks connected by lines and is effective for math-heavy or process control logic, such as PID loops and signal conditioning. Structured Text is a high-level text language, similar to Pascal or C, suited to complex algorithms and data processing. Sequential Function Charts describe process flow as steps and transitions and are particularly useful for sequential control and batch processes.

Digi-KeyŌĆÖs soft-requirements discussion adds another dimension: the software environment should match not only current staff but also the skills of future technicians and engineers, since turnover and promotions will change the team over the life of the PLC. They argue that software consistency across the plant is just as important as language choice, because it affects training time and downtime risk. In a power supply system, where changes to interlocking logic carry real risk, it is particularly valuable to choose a PLC platform and language set that your maintenance staff can read confidently.

Maple Systems highlights several software features that directly affect lifecycle cost and reliability. Online editing lets programmers adjust logic while the PLC is running, which is invaluable when you cannot easily shut down a UPS or power room but must still fine-tune sequences. Simulation modes allow offline testing without hardware, reducing commissioning risk. Automatic device detection, powerful find-and-replace, and cross-referencing tools make large programs easier to understand and modify. Custom function block libraries enable reuse of tested logic, which is especially useful when you standardize transfer sequences or alarm handling across multiple power rooms.

Diagnostic tools are also essential. Maple describes real-time monitoring, logging, hardware and software diagnostics, and clear error codes as core capabilities. c3controls emphasizes the value of comprehensive diagnostics and communications in modern PLCs for remote monitoring and integration. In a power system, these features let you trace the path of a failed transfer or nuisance trip after the fact without guessing.

Cybersecurity is increasingly critical. SimconaŌĆÖs summary notes that a large majority of cybersecurity breaches stem from human error and that many industrial controllers still lack robust authentication, encryption, and regular patching. They advocate strong access controls such as multifactor authentication or username and password pairs, secure and encrypted communication protocols, regular firmware updates, and user education. In a PLC that connects your UPS control system to wider plant or cloud networks, you should check that the platform supports secure protocols, user management, and regular patching, then design your architecture so that critical control networks are appropriately segmented.

As a concrete example, imagine a PLC supervising several UPS modules and feeding status to a building management system. If that PLCŌĆÖs Ethernet port is directly exposed to a corporate network without authentication or encrypted protocols, a misconfigured or compromised office system could potentially reach control logic. Using secure protocols and limiting who can log in and edit code helps prevent such scenarios, in line with SimconaŌĆÖs cybersecurity recommendations.

Power quality and environmental resilience matter just as much as logical functionality. Maple Systems notes that PLC supply voltages commonly include twenty-four or forty-eight volts DC and one hundred twenty volts AC, and that twenty-four volts DC is widely preferred in industrial environments for safety and reliability. They also emphasize the need to match I/O voltage levels, typically five, twelve, or twenty-four volts DC and about one hundred twenty volts AC, to connected devices. c3controls echoes this in their PLC basics guide, describing typical PLC power supplies of twenty-four volts DC or one hundred twenty volts AC, often with battery backup.

In a power room, where you may already have DC control power available for protective relays, choosing a PLC that uses twenty-four volts DC for both its supply and I/O significantly simplifies power system design and improves noise immunity. When higher voltage outputs are needed for contactors or heaters, Maple points out that one hundred twenty volt AC I/O points are appropriate, but they must be carefully coordinated with loads.

Environmental conditions also matter. Industrial Automation Co. urges matching PLC ratings to temperature, humidity, dust, vibration, and electrical noise. Simcona notes that many PLCs are designed to operate reliably across a range roughly comparable to 32 to 130 ┬░F but may require special ratings beyond that. c3controls provides detailed advice on enclosure selection, recommending durable materials such as polycarbonate, ABS, steel, or aluminum, appropriate NEMA or IP environmental ratings, electromagnetic and radio-frequency interference shielding, and verified compliance with UL, NEMA, and IP standards.

In a power supply application, this translates into concrete enclosure decisions. If your PLC sits in a clean, climate-controlled UPS room, a standard NEMA-rated steel enclosure is often enough. If it is near transformers, outdoor switchgear, or areas with heavy dust or moisture, you may need higher environmental ratings and more robust materials. In either case, careful attention to grounding and shielding reduces susceptibility to the electrical noise that is inevitable around large power equipment.

Beyond the datasheet, the strength of the vendor ecosystem is one of the most important, and most often overlooked, PLC selection criteria. Digi-Key emphasizes factory-wide consistency and standardization on one or a few PLC brands, noting that it simplifies technician training, reduces the number of spare parts you must maintain, and makes accessory reuse easier. They note that platforms with broad adoption benefit from strong education and support ecosystems that include vendor training, trade schools, textbooks, and online communities.

R.L. Consulting similarly highlights vendor choice and ecosystem support, recommending established brands for their reliability, broad product lines, and long-term support. Simcona points out that brand choice should reflect application complexity and safety risk, suggesting that for high-risk applications, such as systems involving heavy lifts over workers or high-capacity transportation, a reputable, established manufacturer is worth the premium.

In power supply systems where unexpected downtime carries both financial and safety consequences, those arguments are compelling. When you standardize on one or two well-supported PLC families across your UPS, inverter, and distribution applications, you reduce training time, make it easier for technicians to switch between systems, and improve your chances of finding replacement hardware years down the line.

Digi-KeyŌĆÖs soft-requirements review also notes that future staff will need to understand not just code but also the controlled process, including startup, shutdown, and error-handling edge cases. Their conclusion is that frequent PLC changes are inherently costly and risky. That reinforces the case for choosing a platform you can live with and support for a long time, and then applying disciplined change management rather than bouncing between brands or architectures with each project.

The ForumAutomation safety PLC guidance explains that a safety PLC is specifically engineered and certified to execute safety-related functions under standards such as IEC 61508 and IEC 61511, with defined Safety Integrity Levels. If your risk assessment or governing standard demands a SIL-rated safety function, for example to prevent dangerous overpressure or to protect personnel around high-energy equipment, then a safety PLC with appropriate SIL certification and safety I/O is likely required. For purely non-safety functions such as status monitoring, automatic load transfers with separate protective relays, or noncritical alarm logging, a standard PLC may be sufficient. The decision should be anchored in a formal safety study, but once a SIL target is set, the safety PLC must meet or exceed it and have third-party certification as the ForumAutomation summary recommends.

Industrial Automation Co., Maple Systems, and Digi-Key all warn against underestimating future expansion. It is common to add sensors, actuators, and networked features over the life of a power system as monitoring expectations increase. While none of the sources prescribe a specific percentage, they recommend intentionally over-specifying CPU power, memory, and I/O capacity to accommodate growth. In practice, this means choosing a PLC whose I/O backplane can handle additional modules beyond your initial count and whose CPU and memory can support extra logic and data logging. Using the earlier retrofit example with around one hundred fifteen I/O points, selecting hardware that can grow by at least several dozen additional points and has spare processing and memory capacity would align with that guidance.

ACE contrasts PLCs and distributed control systems historically, noting that PLCs were once aimed at discrete logic with little analog capability, while DCS platforms were designed for large-scale analog process control but with slower scan times. They explain that modern PLCs now support extensive analog I/O and advanced control functions such as PID, feedforward, and dead-time compensation, and that DCS systems have gained more discrete control features. The gap has narrowed considerably.

For smaller process applications, including many stand-alone assets or small process units where a DCS would be cost-prohibitive, ACE argues that a PLC is usually the right fit. For very large, integrated plants with thousands of I/O points and deeply coordinated process control, a DCS may still be the better architectural choice. In the power supply arena, single UPS plants, switchboards, and small power rooms are typically well served by PLCs; only when power control is a tightly integrated part of a massive process complex would a DCS usually be considered.

Selecting a PLC for industrial and commercial power supply systems is not just a matter of matching I/O counts and protocol logos. The most robust designs treat the PLC as a long-lived reliability component, balancing hard specifications like scan time, I/O mix, and environmental ratings with soft factors such as maintainability, vendor ecosystem, and safety certification. When you ground your decisions in a clear understanding of the power process, follow the sizing and performance guidance provided by manufacturers such as Maple Systems, Industrial Automation Co., ACE, and c3controls, and respect the lifecycle and human factors highlighted by Digi-Key, Simcona, and R.L. Consulting, you give your UPS and inverter systems a control platform that will protect both power quality and uptime for years to come.

Leave Your Comment