-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Modern food plants live and die by line uptime, repeatable quality, and documented compliance. As a power and controls specialist, I see the same pattern again and again: the hardware on the floor looks impressive, but the real differentiator is the custom logic in the PLCs, and how well that logic is protected by the power and automation infrastructure around it. When the program is thoughtfully engineered and backed by reliable power, ovens, mixers, freezers, and packaging lines behave like a single coordinated system instead of a collection of fragile machines.

This article walks through how to design, program, and maintain PLC-based control for food processing automation, with a focus on practical, custom logic that respects food safety, productivity, and electrical reliability.

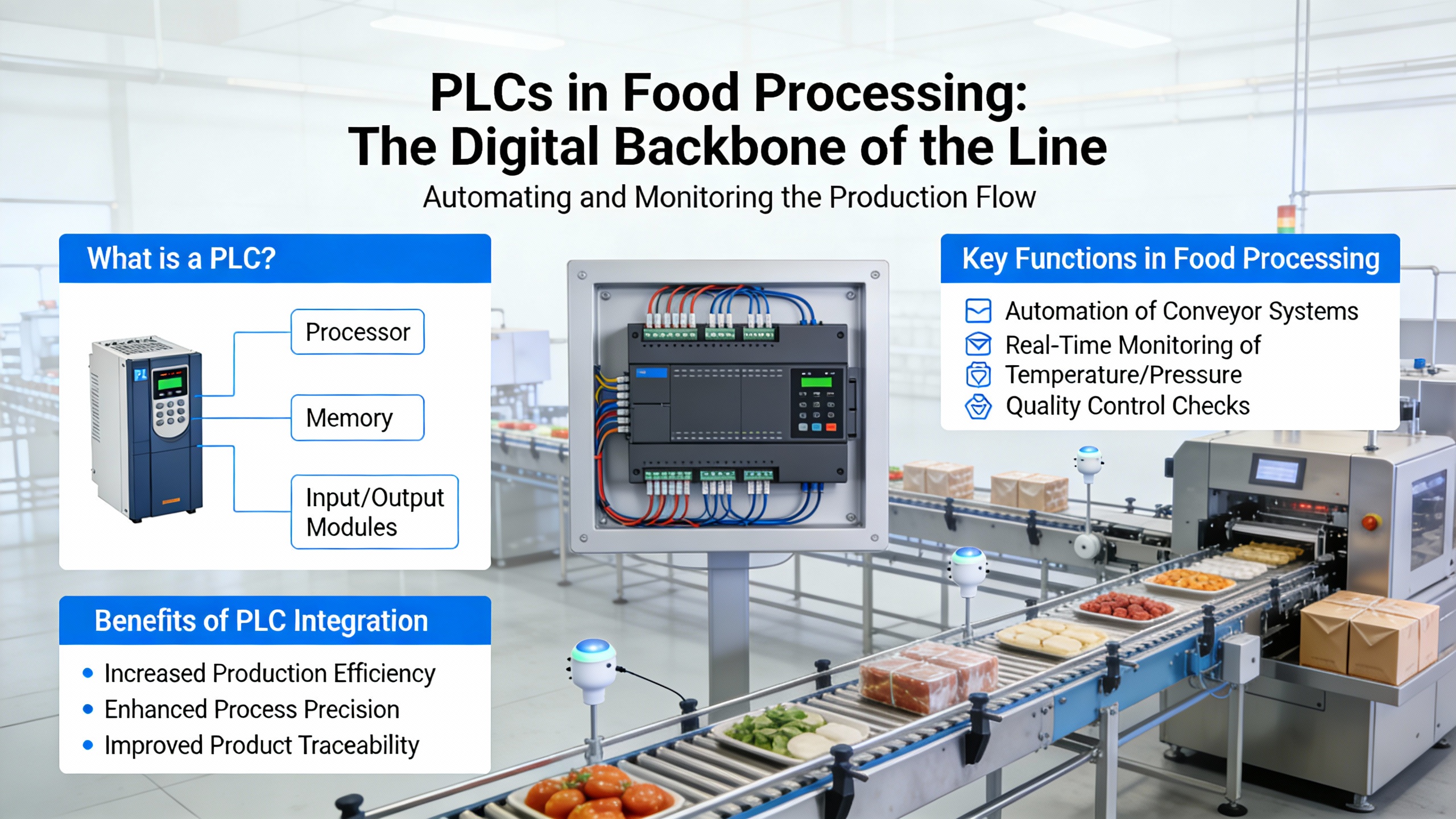

A Programmable Logic Controller is an industrial-grade digital computer designed to monitor inputs, execute programmed logic, and drive outputs in real time. PMG Engineering describes PLCs as the foundational platform that replaced hardwired relay systems at automotive manufacturers like General Motors, a transition originally driven by innovators such as Dick Morley. That shift brought faster troubleshooting, high reliability, and far more flexibility than banks of relays could ever provide.

In food factories today, PLCs sit at the heart of processing and packaging lines. EZSoft Inc notes that in industrial food machines, PLCs typically run filling, sealing, labeling, temperature regulation for food safety, and conveyors for product movement. This is where custom logic matters: the same PLC platform can handle a spiral freezer, a retort, or a carton erector, but only if its program fully reflects the process requirements and constraints of that specific machine and product.

From a hardware perspective, PMG Engineering explains that a PLC system is built around a CPU that stores and executes the logic and retains programs during power loss, a power supply that converts line voltage to about 24 V DC, and modular input/output cards that filter noise and interface with real-world signals. Inputs can include push buttons, limit switches, and sensors; outputs drive motors, solenoid valves, and conveyors. UpKeepŌĆÖs PLC guide reinforces this view, emphasizing that PLCs are rugged systems designed to function in harsh industrial environments as the ŌĆ£brainŌĆØ of production equipment.

Consider a simple example of a sauce filling line. Level sensors in a holding tank feed status into the PLC. The PLCŌĆÖs program opens a valve to refill the tank when level drops below a target, throttles the pump based on a flow transmitter, and coordinates conveyor motion so bottles are under the filler head at the right moment. Every scan cycle, the PLC reads those sensors, executes the logic, and updates outputs within milliseconds, ensuring that sauce is filled accurately and consistently without human intervention at each step.

Both PMG Engineering and UpKeep describe a PLCŌĆÖs operation as a fast, cyclic scan. The controller repeatedly performs three basic steps. It first reads the status of all inputs, such as temperature probes in an oven or a pressure transmitter in a CIP circuit. It then executes the control program, typically written in languages like Ladder Diagram, Structured Text, Instruction List, Sequential Function Charts, or Function Block Diagram, as summarized by EZSoft Inc. Finally, it writes to all outputs, commanding drives, valves, and alarms accordingly.

On a cooking line, this might mean the PLC reads product temperature from several probes, compares each to a critical limit defined for food safety, and then modulates burner output through a control valve. If a probe fails, the logic can force the line into a safe state and raise an alarm on the operatorŌĆÖs screen. Because this scan happens many times each second, the PLC reacts much faster and more consistently than a human operator could.

This deterministic scan cycle is also why clean power is so critical. The power supply converts incoming AC to the steady DC the CPU and I/O require. Voltage disturbances from the plant grid can disrupt that cycle and force unexpected resets, which is why UpKeep recommends power protection and backup power as part of broader safeguarding measures for PLC equipment.

In most modern food plants, the PLC is part of a larger automation ecosystem. UpKeep, EZSoft Inc, and Process Solutions describe this landscape in consistent terms. A PLC or more capable Programmable Automation Controller (PAC) handles deterministic machine control at the line level. Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) software runs at a higher level, visualizing the process, logging data, and handling plant-wide alarming. Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES), as described by EZSoft Inc, sit above SCADA and PLCs to provide real-time production monitoring, traceability, and scheduling, bridging the shop floor with enterprise planning systems.

UpKeepŌĆÖs guide explains related technologies such as DCS (Distributed Control System) built from multiple PLCs, DDC (Direct Digital Control) in building automation, and HMIs that allow operators to interact directly with PLCs. JHFosterŌĆÖs case study of a large industrial bakery illustrates how powerful this integration can be when done well: PLCs from 35 different equipment vendors were unified into a single SCADA platform that managed recipe control, plant-wide alarms, a process historian, and direct data connectivity to the bakeryŌĆÖs ERP system.

The various layers can be summarized as follows:

| Layer | Primary role in a food plant | Typical responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| PLC / PAC | Real-time equipment control | Sequencing, interlocks, safety logic, basic recipes, local alarms |

| HMI | Operator interaction | Setpoint changes, manual controls, alarm acknowledgment, simple trends |

| SCADA | Supervisory monitoring | Plant graphics, centralized alarms, historian, plant utility control |

| MES | Production management | Traceability, work orders, performance metrics, scheduling, compliance reporting |

When these layers are designed to work together, PLC programs do not operate in isolation. They become the reliable, deterministic engine under a data-driven, traceable production system.

PLC programming is the craft of translating process requirements into executable logic. EZSoft Inc calls it the process of writing and debugging logic that automates industrial tasks, and points out that in food manufacturing it is central to consistent quality and efficiency. Off-the-shelf OEM programs can run a machine, but they rarely embody the full HACCP plan, production sequencing, and plant-specific constraints that a food processor actually lives with day to day.

EZSoft Inc notes that PLCs support five standard languages. In food plants, Ladder Diagram is especially common because, as PMG Engineering observes, it resembles electrical relay schematics and is accessible to engineers and electricians. This readability is valuable when operators or maintenance technicians need to understand why a conveyor is stopped or why an oven is not allowing a start. Other languages such as Structured Text and Function Block Diagram can still be used inside the same PLC project, but the guiding principle from Pacific Blue Engineering is to keep logic as simple and straightforward as possible so that the whole team can troubleshoot and adjust it with minimal risk.

Pacific Blue Engineering also emphasizes that effective PLC programming starts before any code is written. Clear objectives must be defined: perhaps faster throughput on a packaging line, lower energy use in a freezer, or tighter control of cook and chill times for food safety. A detailed system architecture map that shows every input, output, communication link, and machine interaction becomes the blueprint for logic design. This is not an academic exercise. If a line has dozens of interdependent conveyors and machine centers, capturing these dependencies on paper first helps avoid hidden deadlocks and unsafe states in the code.

Imagine designing logic for a retort system where product baskets are loaded into a vessel, held at a target temperature, and cooled according to critical limits. With a clear objective for safe lethality and maximum throughput, the PLC programmer can break the logic into modules: basket loading and tracking, heating ramp, hold phase based on multiple temperature sensors, cooling sequence, and fault handling. Each module can then be built with simple conditions that operators can follow, rather than one monolithic, opaque program.

Pacific Blue Engineering recommends organizing PLC code into modular sections, such as startup routines, main process control, alarm handling, and shutdown or emergency behavior. This modular design makes it easier to test each portion in isolation and simplifies troubleshooting when something goes wrong.

A typical food line program might include one routine for system permissives and interlocks, another for recipe execution, another for clean-in-place sequencing, and a dedicated block for alarm generation and logging. These modules interact through well-named tags and flags so that the code effectively documents itself. When this is combined with clear HMI graphics, operators can see, for example, that a bagger is blocked because a downstream conveyor has signaled ŌĆ£full,ŌĆØ rather than assuming the PLC has failed.

UpKeep highlights the importance of diagnostics as well. It points to LED indicators, error histories, and sensor health checks as vital tools. A well-structured program surfaces those diagnostics clearly: fault bits propagate into an alarm summary, and error counters feed data into the SCADA historian or reporting database. EzSoft Inc underscores that robust database design and reporting are central to modern automation, enabling analysis of metrics such as output per shift, downtime causes, and quality metrics. When the PLC program is structured with those data needs in mind, it becomes much easier to diagnose chronic issues and refine process logic over time.

Validation is another critical dimension, especially in regulated sectors like food and pharmaceuticals. EZSoft Inc notes that validation involves testing PLC code, verifying data integrity across integrated systems, and confirming compliance with standards such as FDA regulations. In practice, that means defining acceptance criteria for each module of logic, simulating sequences where possible, and executing structured factory and site acceptance tests before full production use, as also recommended by Pacific Blue Engineering for complex manufacturing systems.

Even the best PLC program cannot deliver value if the controller resets, overheats, or fails under electrical stress. UpKeep emphasizes that PLCs, like any major industrial system, require consistent preventive maintenance: removing dust, maintaining ventilation, changing enclosure filters, checking connections, and replacing worn I/O modules. It also recommends monitoring environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature, using sensors to ensure that PLC enclosures remain within acceptable conditions.

From a power perspective, PMG Engineering highlights that the PLCŌĆÖs power supply converts the plantŌĆÖs line voltage into stable DC for the CPU and I/O. UpKeep warns that if input and output devices are frequently burning out, power spikes or shorts may be a root cause, and suggests employing backup power sources and power protection. In practice, this is where UPS systems, conditioned power supplies, and proper grounding enter the picture. Feeding PLCs, HMIs, and critical network switches from a properly sized UPS protects against short outages and voltage dips that could otherwise drop the CPU and stop the line.

As a reliability advisor, I treat power protection as part of the control system, not a separate accessory. A short loss of supply to a PLC controlling a tunnel oven can leave partially baked product stranded. A brief surge on a panel without surge suppression can stress I/O modules and instrumentation, leading to intermittent faults that are notoriously hard to debug. The modest additional cost of UPS-backed and protected control power is often repaid the first time it prevents even a single unplanned stop.

Pacific Blue Engineering stresses software maintenance and backups as equally important. Applying firmware and software updates improves security and compatibility with newer devices, while routine backups of PLC programs provide a safety net after power outages or hardware failures. UpKeep recommends that facilities back up their PLC data at least twice a year, and many plants adopt even more frequent cycles for critical lines. When backups are combined with hardware safeguards such as low-dust enclosures, filters, and power protection, as UpKeep suggests, the overall lifespan and reliability of the automation system increase substantially.

UpKeepŌĆÖs maintenance checklist aligns closely with what I see in well-run plants. Dust removal inside panels and on I/O cards prevents heat buildup and contamination. Regular inspection of plugs, terminals, and mounting hardware is especially important in areas with high vibration, where loose connections can cause intermittent faults and increased contact resistance. Visual inspections for discoloration or burning smells, along with attention to LED status indicators, often reveal small problems before they become big outages.

Calibration of instrumentation used by the PLC, such as flow meters, temperature transmitters, and level sensors, is another critical step. UpKeep suggests including device calibration, including circuit cards, in a preventive maintenance program on a recurring schedule. Those calibrations are particularly important when the PLC logic is enforcing HACCP critical control points like cook temperature, holding time, or cooling rate. If the sensor is off, even the most carefully written PLC code cannot keep the process within safe limits.

UpKeep also urges manufacturers to inventory their PLCs, standardize on a single brand when feasible, and ensure that at least one person per shift knows how to operate and maintain them. Standardization simplifies spares and training, and a complete inventory makes it easier to coordinate firmware updates and backups. These recommendations dovetail with the integration perspective from JHFoster and EZSoft Inc, where long-term maintainability and future modifications depend on good documentation and consistent platforms.

Several of the sources implicitly connect power quality with PLC reliability. PMG Engineering describes the PLC power supplyŌĆÖs role in generating clean DC power. UpKeep mentions power spikes, shorts, electromagnetic interference, and the use of backup power and power protection to safeguard equipment. Building on those points, a robust design for PLC-driven food lines treats control power quality as a first-class requirement.

Practically, that means feeding PLCs, HMIs, and critical network gear from dedicated circuits, protecting those circuits with surge suppression, and in many cases backing them with an uninterruptible power supply or an inverter system. The UPS or inverter does more than keep the PLC alive through an outage. It also smooths over short disturbances that would otherwise reset the controller mid-batch and provides enough ride-through time to bring equipment to a controlled stop if a longer outage occurs.

Because many PLC CPUs and I/O modules operate from around 24 V DC, the UPS-backed source can supply a stable AC feed to the panel power supply. The power supply then continues to deliver the DC rails without interruption. When matched with proper grounding and physical separation from high-current power wiring, as UpKeep advises for avoiding electromagnetic interference, this approach dramatically reduces nuisance trips and erratic behavior that can be misdiagnosed as software defects.

Standalone PLC programs can run machines, but integrated PLC, SCADA, and MES architectures turn them into a coordinated manufacturing line. JHFoster warns about ŌĆ£islands of automationŌĆØ in complex plants that use multiple PLC brands and unconnected subsystems. Without integration into a common SCADA system, data and control remain siloed, undermining both efficiency and traceability.

In the industrial bakery case JHFoster describes, PLCs from 35 equipment suppliers were integrated into a single SCADA platform. That system handled recipe management, plant-wide alarming, a process historian, and connectivity to the bakeryŌĆÖs ERP system. CELCO developed standard PLCŌĆōSCADA interface maps, graphics, and a centralized utility control system. The result was a highly automated facility where operations, procedures, and products were streamlined and standardized, and where future equipment purchases now follow the same information exchange standards.

EZSoft Inc characterizes the broader benefits of this kind of integration. By linking PLCs with MES and database tools, manufacturers can collect and analyze production output per shift, downtime and its causes, and quality metrics to spot trends and meet regulatory requirements. When PLC logic is written with this integration in mind, it exposes meaningful states and measurements, not just discrete on/off signals. That, in turn, gives MES applications what they need to support real-time scheduling, resource allocation, and end-to-end traceability.

Actemium describes a case where a food manufacturer consolidated recipe management directly inside the PLC program and allowed operators to make real-time recipe and process adjustments via HMIs. In this architecture, the PLC acts as the central brain for sequencing, logic, and interlocks, while HMI screens provide operator-friendly access to setpoints, batch sizes, and product variants. Field devices such as heat exchangers, flow meters, and temperature transmitters are tightly integrated into the logic, allowing the PLC to enforce correct process behavior for each recipe.

The benefits reported in that case were significant: enhanced operational efficiency through reduced manual labor and streamlined process steps, higher precision and adaptability as recipes could be adjusted central to the PLC, cost savings from reduced material waste and better utilization of equipment and utilities, and improved compliance and quality assurance thanks to consistent, automated recipe execution.

For a food processor, centralizing recipe logic in the PLC can also simplify validation. The same program that controls the valves and drives holds the recipe parameters, so testing and documenting behavior for a given product is more straightforward. When integrated with MES and historians as EZSoft Inc recommends, the PLC can log which recipe was active, which lot of ingredients was used, and which alarms occurred during each batch, providing a robust record for auditors.

Regulated environments demand that PLC-based automation support not just efficient production, but demonstrable control over food safety and product quality. EZSoft Inc highlights validation as a non-negotiable step in sectors like food and pharmaceuticals. This includes testing PLC code, verifying data integrity across PLC, SCADA, and MES, and ensuring compliance with standards such as those enforced by the FDA.

In practical terms, this means developing test protocols that trace back to your HACCP plan. Critical control points, such as cooking temperatures, holding times, or cooling profiles, are encoded as parameters and logic in the PLC. The automated system must monitor these variables continuously and take predefined corrective actions when limits are exceeded, as general PLCŌĆōHACCP guidance suggests. A well-designed PLCŌĆōHMIŌĆōSCADA stack logs all of this activity with timestamps, creating electronic records that support traceability and verification far more reliably than manual paper logs.

EZSoft Inc also emphasizes robust database design and reporting. When PLC data is stored in well-structured databases, food manufacturers can generate regulatory reports, analyze recurring deviations, and refine their HACCP plans based on actual plant history. MES systems, when integrated with PLCs, provide real-time production monitoring and traceability, improve scheduling and resource allocation, and connect shop-floor conditions directly to business-level decisions.

Security cannot be ignored in this context. EZSoft Inc cites a Kaspersky Labs study in which 21 percent of manufacturers reported security breaches and loss of intellectual property. It therefore recommends integrating security features such as data encryption, password protection, and authentication directly into PLC systems and discussing these capabilities with system integrators. For a food plant, that means ensuring only authorized personnel can change PLC programs, recipes, or critical limits, and that network paths from PLCs to SCADA or MES are protected.

Selecting a PLC for a food processing line is not simply a matter of picking a familiar brand. PMG Engineering and Process Solutions describe several technical considerations: environmental ratings compatible with washdown or high-temperature areas, adequate I/O capacity and modularity for future expansion, support for required communication protocols to talk with drives, HMIs, and MES, and appropriate safety certifications where needed.

PLC vendors such as Siemens, Allen Bradley, and Schneider Electric are commonly used in food factories, according to PMG Engineering. UpKeep recommends standardizing on a single brand where possible to streamline training, spares, and maintenance. That recommendation aligns with the integration and commissioning guidance from JHFoster, which stresses the importance of common standards for PLCŌĆōSCADA communication, and with EZSoft IncŌĆÖs positioning as an end-to-end provider that can program PLCs, integrate systems, design databases and reporting, and deliver training and validation services.

There is also a human side to this decision. EZSoft Inc notes that basic PLC programming, for example using Ladder Diagram, is approachable, but mastering PLC programming and system integration requires extensive practice and deep understanding of industrial processes. Pacific Blue Engineering reinforces this by highlighting the need for role-specific training so operators and maintenance personnel can safely adjust and troubleshoot the systems. In many food plants, the most effective model is a partnership: in-house engineers and technicians who understand the products and process deeply, supported by experienced system integrators who bring best practices in programming, commissioning, validation, and security.

An example helps illustrate the trade-offs. A mid-size sauce manufacturer might start with OEM PLC programs on individual kettles and packaging machines. As volumes grow and product variety increases, they may see frequent changeovers, inconsistent batch records, and difficulty diagnosing downtime. By working with an integrator, they can migrate to a standardized PLC platform, centralize recipe control in the PLC and HMI, integrate those controllers into a SCADA and MES stack, and add UPS-backed power and structured maintenance procedures. The result is not just more automation, but a more resilient and traceable production system that supports future growth and regulatory audits.

Q: How important is it to back up PLC programs and data on a food line? Backups are essential for reliability and compliance. UpKeep recommends backing up PLC data at least twice a year, and many plants schedule even more frequent backups for critical lines. Pacific Blue Engineering notes that routine backups allow quick recovery from power outages, hardware failures, or unexpected events. When a PLC CPU or I/O card fails, restoring a known-good program and configuration can turn a multi-hour outage into a short interruption, and consistent historical backups support investigations and regulatory reporting.

Q: Where should recipe management live: in the PLC, SCADA, or MES? There is no single answer, but the trend in real projects is toward tightly integrating these layers. Actemium describes a successful case where recipe management was consolidated inside the PLC, with operators able to make real-time adjustments through HMIs. That approach simplifies deterministic control and validation. EZSoft Inc, however, highlights the advantages of integrating PLCs with MES and robust databases for traceability, scheduling, and reporting. A practical approach is to let the PLC enforce real-time recipe execution and critical limits while SCADA and MES manage higher-level recipe libraries, approvals, and historical tracking.

Q: Do PLCs for food lines really need special attention to power quality? The sources agree that power quality and protection are important. PMG Engineering explains that PLCs depend on power supplies that deliver stable DC voltage, and UpKeep warns that frequent device failures may be tied to power spikes or shorts, recommending backup power and power protection. In a food plant, a brief power disturbance that resets a PLC can stop a line mid-batch, create product waste, and disrupt schedules. Protecting PLCs and critical network gear with proper power supplies, surge suppression, and often UPS-backed circuits is a practical reliability investment rather than a luxury.

A food lineŌĆÖs PLC logic is only as strong as the power, integration, and maintenance practices that surround it. When you pair well-structured, validated PLC programs with robust power protection, disciplined preventive maintenance, and thoughtful integration into SCADA and MES, you move beyond mere automation and into dependable, auditable production. That is the standard food manufacturers should aim for if they want their control systems to support growth instead of becoming another source of risk.

Leave Your Comment