-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In industrial and commercial power supply systems, the control layer often becomes the hidden bottleneck. When you design a UPS, inverter, or power protection system around a PLC, your future scalability depends on one small but critical detail: the lead time of PLC expansion modules. You can have the best oneŌĆæline diagram in the world, but if your panel builder is waiting thirty or forty weeks for extra I/O, your upgrade plans stall and your reliability assumptions fall apart.

As a reliability advisor, I increasingly see project schedules dictated not by bus duct or transformers, but by the availability of very specific PLC modules. Component shortages have pushed PLC lead times to as much as a year in some cases, as highlighted by Simcona, while MRPeasy reports that many electronic components now sit in the twelve to forty week range. That is simply too long to treat expansion as an afterthought.

This article walks through how to think about PLC expansion modules as a lead-time and scalability problem, not just a hardware choice, and how to plan power system projects so your UPS and power protection expansions land on time instead of waiting on a backordered card.

A programmable logic controller is the core of many industrial and material-handling control systems, as Simcona points out. It reads field inputs, executes control logic, and drives outputs in real time. For modern power systems this includes contactor coils, breaker status, alarms, and analog measurements from sensors. As systems grow, the original I/O count that looked generous during design quickly becomes tight.

This is where PLC expansion modules come in. Cognitive Market Research describes them as addŌĆæon hardware that extends the I/O capacity and functionality of a base PLC. In practice, that means additional digital inputs and outputs, analog channels, specialty functions such as highŌĆæspeed counters or communication adapters, and often remote I/O racks that let you extend control into new gear sections.

Maple Systems distinguishes between fixed PLCs, where CPU, communications, and I/O are tightly integrated, and expandable modular PLCs. Expandable designs let you snap new I/O modules onto a rack or plug them into a remote I/O bus. Simcona stresses that you should design for present needs and future growth: scalable architectures with expansion modules, flexible racks, and communication interfaces allow you to grow without a complete control system replacement.

In the power domain, that scalability translates into practical questions such as whether you can add future UPS strings, extra distribution breakers, or more monitoring points without ripping out the existing PLC. Modular platforms designed with expansion in mind, combined with thoughtful I/O allocation, give you the option to add capacity when the facility expands, rather than overbuying a larger controller upfront.

However, that flexibility only pays off if you can actually get the expansion modules when you need them. That is where lead time becomes the central constraint.

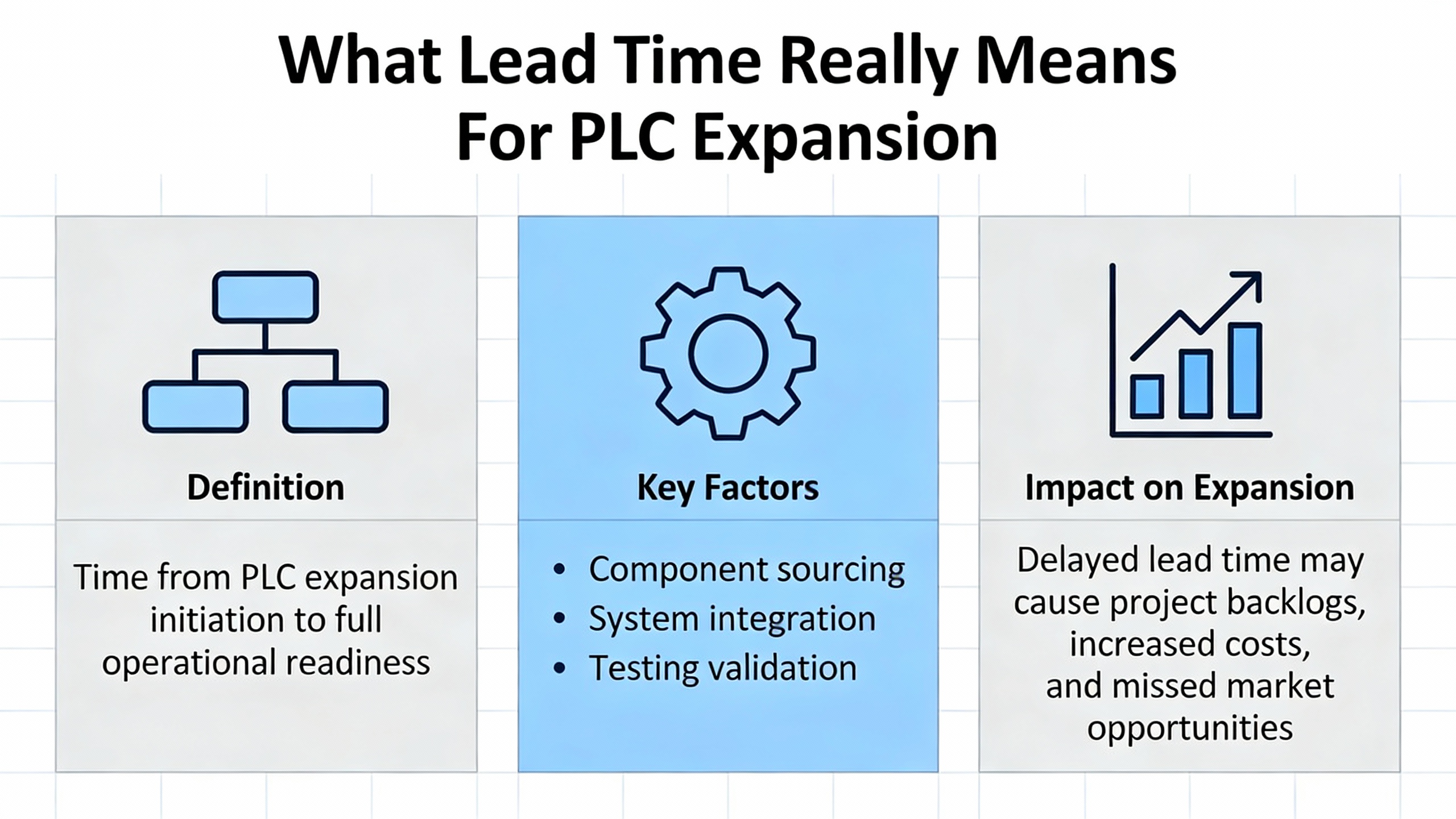

Multiple sources converge on a simple idea: lead time is the total elapsed time between triggering an order or production step and receiving goods ready for use. CAI Software, MRPeasy, Amper, and Conger all emphasize that you must think in terms of endŌĆætoŌĆæend elapsed time, not just the ŌĆ£days in transitŌĆØ that show up on a shipping report.

In the context of PLC expansion modules for power projects, several lead time components matter.

There is procurement lead time, covering vendor selection, purchase order creation, approvals, and supplier confirmation. CAI Software and Amper describe this as the preŌĆæprocessing or planning phase.

There is supplier or material lead time, the period from order acceptance to the hardware arriving at your dock. MRPeasy notes that for many electronic components this can now run twelve to forty weeks. Simcona points out that under ongoing component shortages, PLC lead times can stretch to a full year.

There is internal handling and production lead time, including receiving, inspection, panel assembly or modification, testing, and commissioning. CAI Software describes this as processing and postŌĆæprocessing time: actual manufacturing work, inspection, packaging, and delivery.

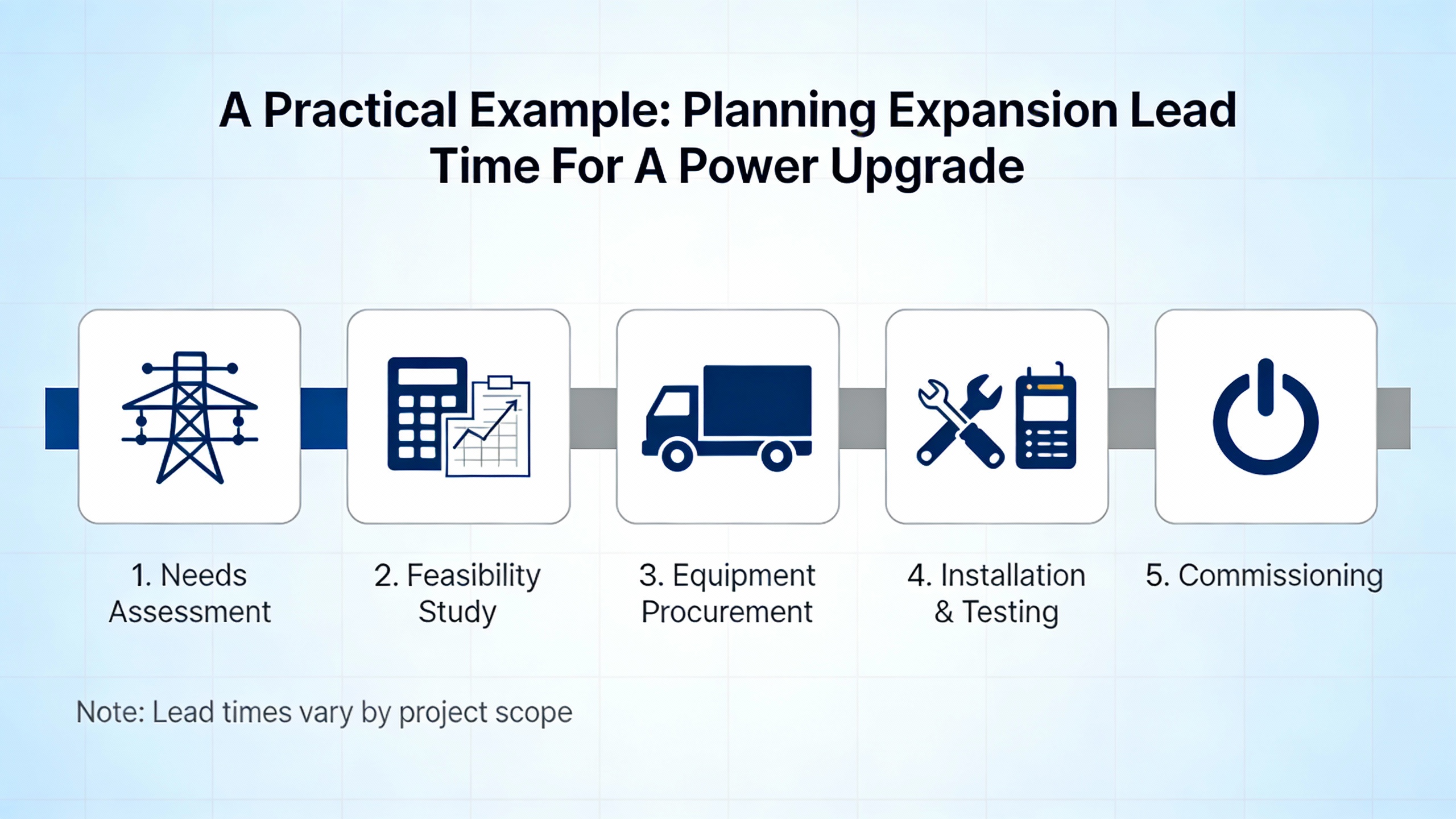

When you combine these, you get a cumulative lead time that determines how far in advance you must commit to expansion decisions. Amper and CAI Software both express this with simple formulas such as total lead time being preŌĆæprocessing time plus processing time plus postŌĆæprocessing time.

To illustrate the effect, imagine you are planning to add a new UPS output section that requires two extra digital I/O modules and one analog module. Suppose it takes two weeks to clear internal approvals and generate a purchase order, twentyŌĆæsix weeks for the vendor to ship the modules, and three weeks for the panel shop to modify the control cabinet, test, and deliver. Using the cumulative view, your expansion lead time is two plus twentyŌĆæsix plus three, or thirtyŌĆæone weeks. You cannot start that project in September and expect it to be online for a January load addition unless you already have the modules in hand.

That is why manufacturers like MRPeasy argue that lead time is not just one more KPI; it becomes the core constraint behind realistic customer promises and production schedules.

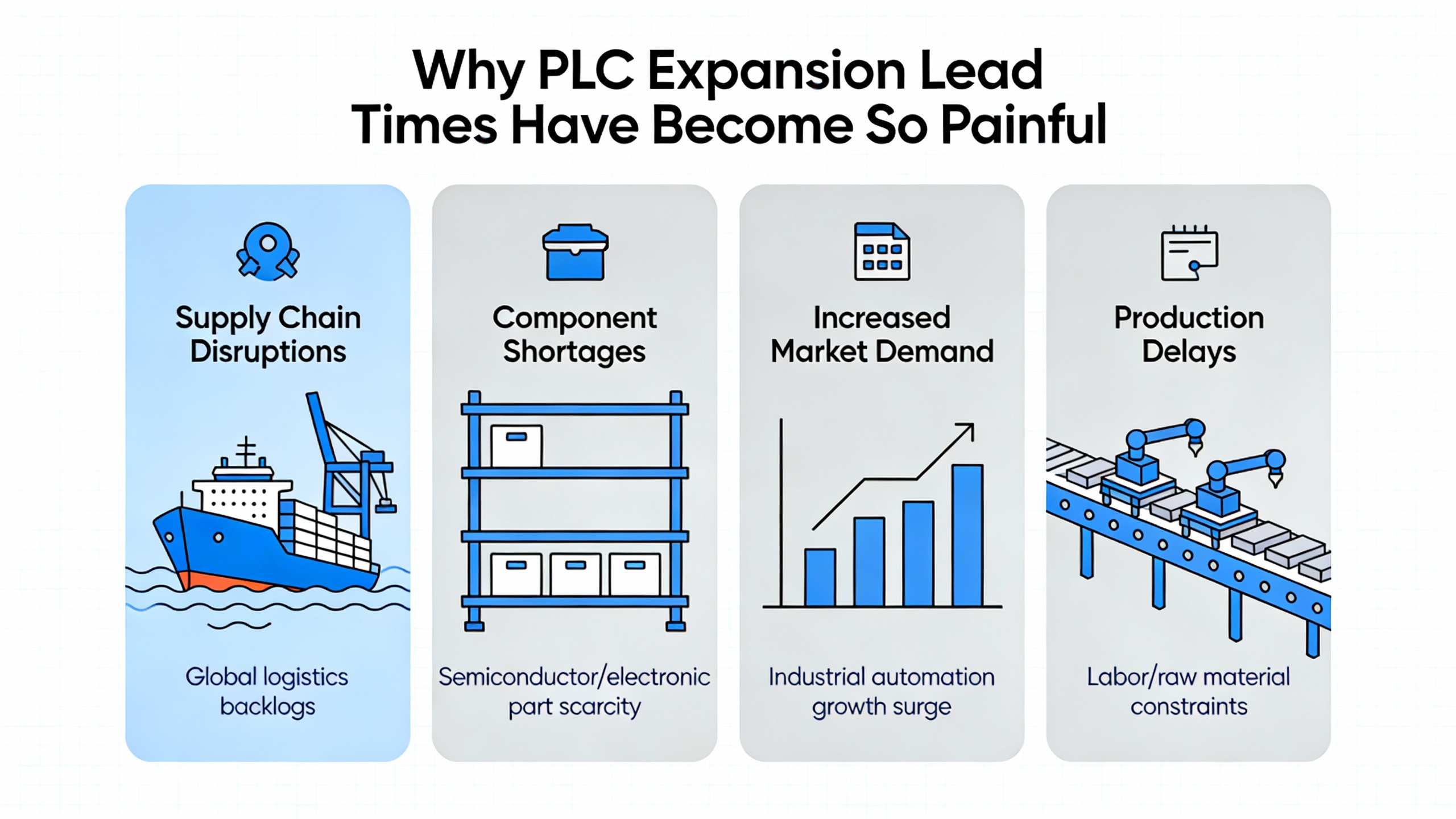

Lead time problems on PLC expansion modules are not an isolated curiosity of automation vendors; they are a symptom of broader supply chain trends affecting electronics and industrial hardware.

MRPeasy highlights that average raw material delivery lead times increased from sixtyŌĆæfive to eightyŌĆæone days, roughly a twentyŌĆæfive percent jump, and that supply disruptions now cost manufacturers about eight percent of annual revenue. They also note that many electronic components, including capacitors and semiconductors, sit in the twelve to forty week lead time range. When you build PLC CPUs and I/O cards on top of those components, it is no surprise that entire PLC families are heavily delayed.

Simcona explicitly warns that ongoing electronic component shortages have pushed PLC lead times out to as much as a year. That aligns with what many integrators and panel shops report: once a specific module goes on allocation, your project becomes a hostage to that part number.

The problems of long and variable lead time are not just about waiting. The Aalto University masterŌĆÖs thesis on lean and agile supply chains explains how long, opaque chains amplify demand variability up the upstream stages, a phenomenon known as the bullwhip effect. With poor visibility, small changes in endŌĆæcustomer demand for power upgrades ripple into large swings in orders for PLC hardware higher in the chain. Manufacturers respond with bigger safety stocks or more aggressive ordering, which can make shortages worse.

Conger, Plex (part of Rockwell Automation), Amper, and CAI Software all describe how long lead times force higher inventory levels, increase the risk of obsolete hardware, and complicate scheduling. TargetŌĆÖs failed Canadian expansion, referenced by Plex, is an extreme example from retail, where long lead times combined with poor product fit produced empty shelves in some places and useless inventory in others, eventually contributing to about two billion dollars in losses. The principle is the same in power systems: if you commit to one PLC platform and then cannot get expansion modules, you may find yourself with completed switchgear and no viable control system for months.

For power supply projects, the stakes are high. A missed UPS upgrade date can delay tenant occupancy, data hall commissioning, or regulatory acceptance testing. Long and uncertain lead times for PLC expansion modules therefore must be treated as a primary design constraint, not an afterthought.

Given these constraints, the first major decision is architectural: do you oversize the base PLC now, rely on expansion modules later, or accept that you may eventually change controller families? Maple Systems and Simcona both emphasize that compatibility and scalability must be considered up front, not left to future engineers.

Maple Systems describes a clear tradeoff between fixed and expandable PLC designs. Fixed PLCs integrate CPU, I/O, and communications in a compact package, which is attractive for small, stable applications. Expandable PLCs, by contrast, allow you to add or swap I/O and specialty modules as needs evolve. Simcona adds that you should design for present and future by checking compatibility with existing systems and choosing architectures that accept expansion I/O, flexible racks, and easily integrated communications interfaces.

Plant Automation Technology underscores that scalability and flexibility are core strengths of PLCŌĆæbased automation. They emphasize that wellŌĆædesigned PLC systems can be expanded, reprogrammed, and integrated with existing equipment to support new lines and modified processes.

In power system projects, this architecture decision drives how exposed you are to expansion lead time. If you choose a small fixed PLC with no room for extra I/O, any significant growth may require replacing the controller, rewriting logic, retesting interlocks, and possibly reŌĆæcertifying panels under standards such as NFPA 79 and UL 508A, both identified by R.L. Consulting as key references for control panels and industrial machinery. That is a substantial downtime and engineering hit on top of procurement lead time.

If you choose a modular PLC and leave physical rack space for expansion modules, you only need the new modules and incremental logic changes when you expand. However, you then depend on those specific modules being available in time.

A practical way to frame the choice is to compare three approaches: oversizing the base PLC now, relying predominantly on future expansion modules, or planning for controller replacement later. Maple SystemsŌĆÖ guidance on CPU speed and memory sizing is relevant here; underŌĆæspecifying CPU and memory can make future expansions hard or impossible, while grossly oversizing adds cost without necessarily solving module availability problems.

A simple comparison helps illustrate the tradeoffs.

| Approach | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Oversize base PLC and I/O now | Fewer expansion orders later, simpler lifecycle for logic, less risk from module lead times | Higher upfront cost, potentially unused I/O, possible obsolescence before use |

| Modular PLC with reserved rack space | Flexible, growth via expansion modules, smaller initial spend, aligns with scalable design | Strong dependence on specific modules, exposed to long lead times, careful part management |

| Minimal now, accept future replacement | Lowest initial cost, avoids overŌĆædesign | Future changeover downtime, reprogramming and retesting effort, higher lifecycle risk |

In my experience, power projects that treat expansion as a firstŌĆæclass requirement usually pick the second path but mitigate lead time risk through spare strategy and supplier agreements, rather than gambling on future controller replacements.

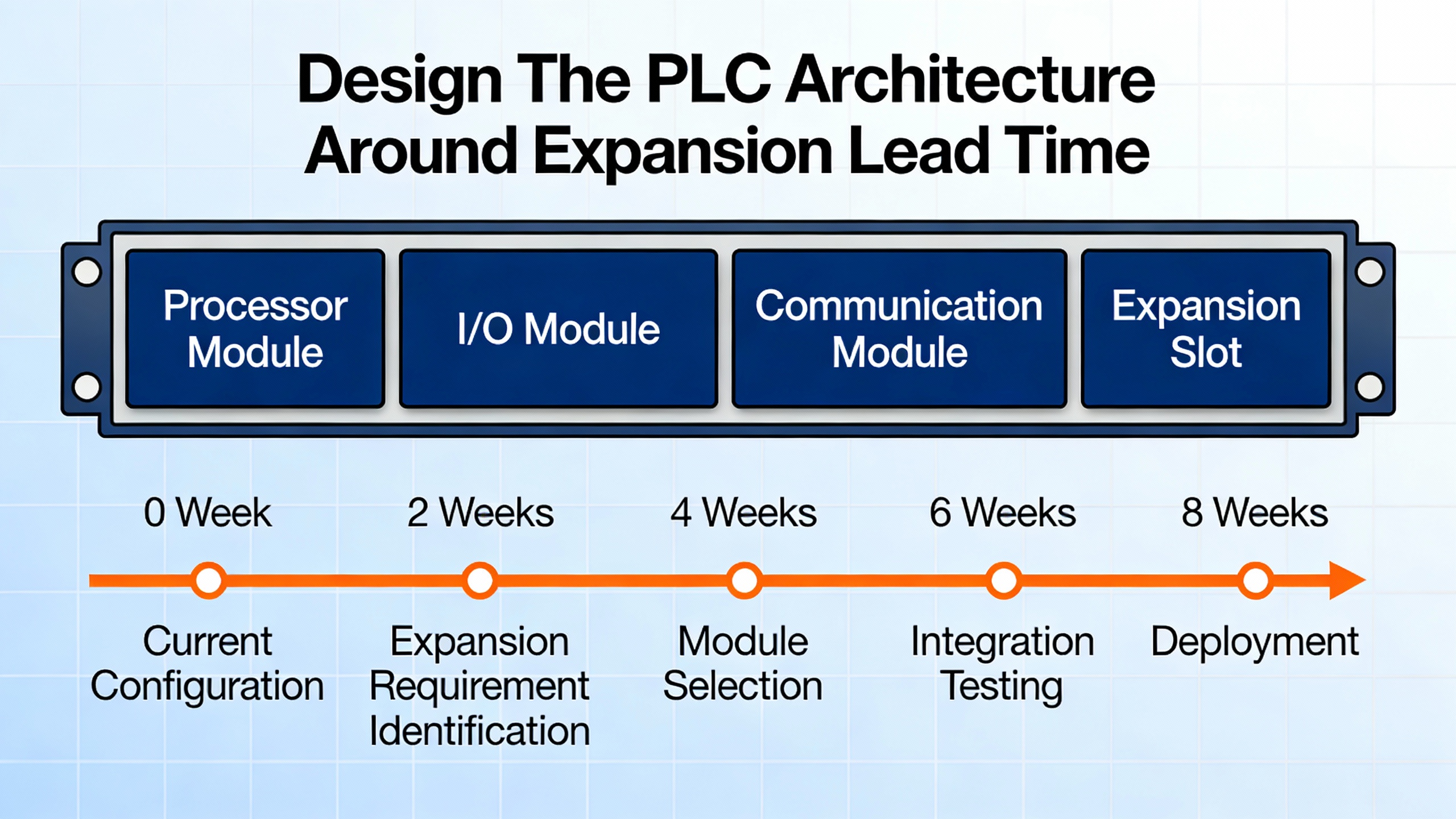

Once the architecture choice is clear, the next step is to quantify how lead time interacts with your expansion roadmap. MRPeasy stresses that consistent leadŌĆætime measurement and planning are essential, including clear definitions of when timing starts and ends and how backlog is handled. They recommend linking lead time planning to actual capacity, including work already in the queue.

Imagine a facility that plans to add two new UPS modules and a downstream power distribution expansion in three phases over five years. From previous projects, you know each phase requires six extra digital I/O channels and four analog channels. Maple SystemsŌĆÖ guidance on I/O selection reminds you that digital I/O handles on/off signals while analog handles continuous variables such as temperature and pressure. You also plan to add a communication module in the second phase to integrate with a higherŌĆælevel monitoring system.

Using MRPeasyŌĆÖs approach, you first define your lead time for each type of module. Suppose recent history and supplier feedback show a median procurement and delivery lead time of twentyŌĆæfour weeks for digital modules, thirty weeks for analog modules, and thirtyŌĆæsix weeks for communication modules. Internal panel modifications and commissioning add another four weeks.

For each phase, you can now calculate cumulative expansion lead time by module type, using the simple structure from Amper and CAI Software. For analog modules in phase two, for example, you might estimate two weeks of planning and approvals, thirty weeks of supplier lead time, and four weeks of internal work, for a total of thirtyŌĆæsix weeks. If phase two is scheduled to go live in January of a given year, your last responsible order date for those analog modules falls around the previous March or April. Any slip in ordering pushes directly into your goŌĆælive window.

This kind of calculation is not sophisticated, but very few power project teams do it explicitly for PLC expansion modules. More often, they treat PLC I/O as an afterthought on the general bill of materials, without adjusting delivery and commissioning milestones for the reality that those modules might be on thirty week lead times while other components arrive in eight.

The Aalto University thesis on lean and agile supply chains suggests another lens: identify where in the value chain you place your control point. For PLC expansion modules, that control point is effectively the moment you lock in your platform and commit to ordering specific modules. Placing that control point earlier in the project gives you more options to buffer lead time with inventory or design changes. Placing it late removes flexibility and increases the chance that a single late module will slip the entire UPS or power distribution upgrade.

While you cannot fix global semiconductor shortages, you can apply proven supply chain and manufacturing practices to reduce or at least stabilize lead times for PLC expansion modules.

Several sources converge on supplier strategy. MRPeasy, Conger, and Amper all recommend choosing reliable, often more local suppliers and building stronger relationships. Conger notes that favoring domestic or nearby suppliers helps avoid the thirty to forty day shipping delays, customs, and returns complications that come with distant sources, even if unit costs rise. For PLC hardware, this may translate into working with distributors who hold local stock of critical modules or partnering with panel manufacturers that have robust supply networks, as Simcona recommends.

Amper and MRPeasy emphasize the importance of sharing accurate, forwardŌĆælooking demand signals with suppliers. Providing quarterly forecasts or expansion roadmaps for your PLC needs gives suppliers room to align production and inventory with your plans. Amper suggests formal supplier lead time contracts that define acceptable delivery windows and penalties for late shipments. In practice, this can be difficult for commodity PLC modules, but even a soft agreement on expected volumes and timing can put your orders in a better position during allocation.

Conger and MRPeasy also point to order sizing as a lever. Smaller, more frequent orders can sometimes shorten lead times and reduce inventory risk. However, for PLC expansion modules with very long lead times, the opposite may be more practical: placing fewer, larger orders that cover multiple phases of expansion. That way you endure the long lead time once, then hold a modest inventory of expansion modules that you draw down over time.

CAI Software and Plex highlight the role of systems and automation. Integrated manufacturing software, such as MES and ERP, with realŌĆætime inventory management, can track PLC module stock, trigger reorder points, and calculate expected replenishment lead times. CAI Software notes that this kind of integration improves forecast accuracy, reduces stockouts, and lowers storage costs by maintaining healthier inventory levels.

From a plantŌĆælevel perspective, OrcaLean points out that better supplier coordination, including shared forecasts, vendorŌĆæmanaged inventory, and performance monitoring, helps shrink material lead time. In some industries, this means giving suppliers direct visibility into demand signals and inventory levels so they can replenish automatically within agreed bounds. For PLC modules, that might look like a distributor agreement to always keep a defined number of your key expansion modules reserved or on consignment.

None of these tactics eliminates the underlying component shortages, but they shift your position in line and reduce uncertainty. The difference between a stable twentyŌĆæfour week lead time and a highly variable twelve to forty week lead time is enormous for power system projects that cannot easily move commissioning dates.

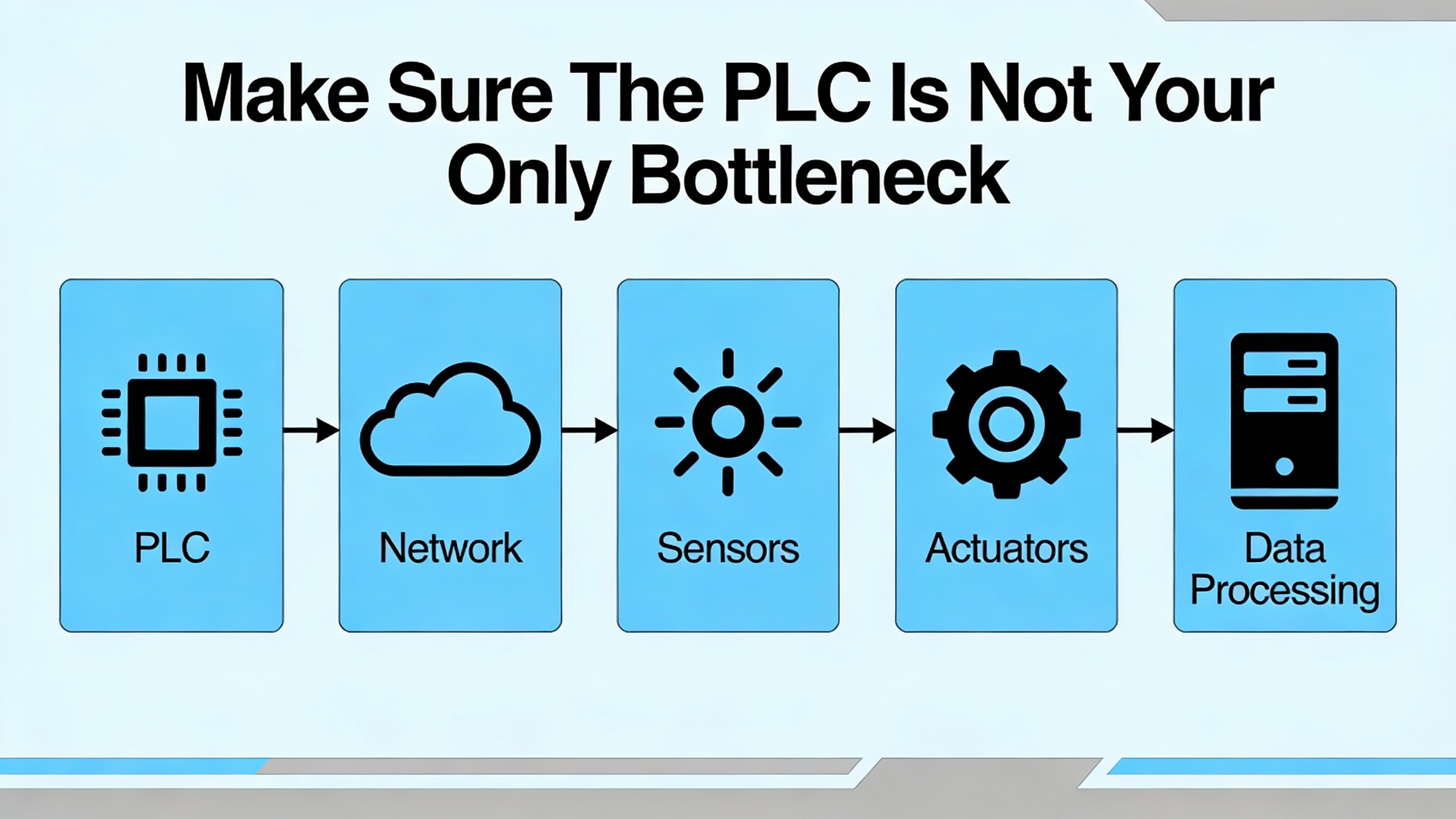

Manufacturing experts like CAI Software, OrcaLean, Seco Tools, and Conger consistently point out that long lead times are rarely driven by one single factor. Even if your PLC expansion modules arrive on time, poor internal processes can waste weeks.

Seco Tools explains that pushing equipment utilization toward one hundred percent actually lengthens lead times, because any unplanned downtime then creates bottlenecks. They suggest that an eighty to eightyŌĆæfive percent utilization level is typically optimal, with enough spare capacity to absorb disruptions. Applied to power system projects, that means your panel shop or field commissioning teams need a realistic loading plan; if they are already overcommitted, your expansion module lead time is not the real constraint.

OrcaLean recommends mapping your process with tools like value stream mapping, identifying queue times, rework loops, and nonŌĆævalueŌĆæadded activities. They emphasize that reducing workŌĆæinŌĆæprogress and batch sizes exposes defects earlier and shortens lead time even if total output per shift does not change. For control panels, this might mean building and testing smaller sets of boards in a continuous flow rather than batching ten panels at a time, which aligns with lean principles.

CAI Software and Amper argue for automating order entry, approvals, inventory management, and material pulls. Manual paperwork, emailŌĆæbased approvals, and spreadsheet tracking inject hidden days of delay. When PLC expansion modules are on twentyŌĆæplus week lead times, losing another week inside your own organization because a purchase request sat on someoneŌĆÖs desk is needless waste.

In concrete terms, consider an internal process where engineering completes I/O lists and panel drawings, then manually sends a spreadsheet to purchasing, which then routes it for approval, finally creating a purchase order for PLC modules. If each handoff takes several days and nothing is tracked automatically, you can easily accumulate two or three weeks of internal lag before an order is even visible to the supplier. By adopting digital workflows that trigger approvals immediately and track status in real time, you can cut that preŌĆæprocessing time to a few days.

When you combine trimmed internal delays with the supplierŌĆæfacing tactics described earlier, the practical effect on PLC expansion module lead time can be substantial, even if the base semiconductor supply constraints remain.

Lead time planning for PLC expansion modules is not only a project delivery issue; it is a longŌĆæterm reliability and maintenance issue. R.L. Consulting defines PLC system maintenance as the ongoing process of keeping controllers and related components operating as intended. They stress that proactive maintenance in highŌĆæthroughput industries such as pulp and paper, steel, textiles, automotive, and rubber reduces unexpected failures and safety risks.

Their bestŌĆæpractice recommendations include regular inspection of control panels, I/O and communication modules, wiring, grounding, environmental conditions, software backups, and safety function tests. They also highlight the importance of identifying obsolescence early and planning retrofits.

Long lead times for PLC modules mean that a module failure or obsolescence surprise might leave you unable to restore full capability quickly. If your power system logic depends on a specific analog input module that is now obsolete and hard to source, you might face an unplanned controller replacement during a maintenance window that was not sized for such a change.

That reality supports a more deliberate spares and lifecycle strategy for expansion modules. Instead of treating expansion modules as oneŌĆæoff purchases for specific projects, it can be prudent to maintain a small, documented stock of critical I/O and communication modules that are known to be used across multiple panels and projects. MRPeasy notes that supply disruptions can cost around eight percent of revenue; while this figure is at the manufacturing level, it illustrates how expensive lost production can be compared with the cost of holding a few key spares on the shelf.

Mikrodev, in their discussion of calendar and timing functions in PLC programming, underlines the importance of planned maintenance windows and timeŌĆæbased control. By leveraging calendar functions to schedule maintenance and timing functions to enforce maintenance durations, you can create predictable slots in which any needed PLC work, including swapping expansion modules, can occur. That, in turn, reduces the risk that an unplanned module failure collides with critical production or service windows in your power system.

Plant Automation Technology emphasizes that testing and commissioning of PLC systems, including validation of control algorithms, interlocks, and safety functions, are essential for avoiding errors and malfunctions after goŌĆælive. Every time you insert new expansion modules and modify logic, you should treat the change as a miniŌĆæcommissioning project, with clear test plans and rollback options. Long lead times make rework expensive; catching logic issues during a wellŌĆæplanned maintenance window is much cheaper than discovering them during an unplanned outage.

To make these ideas concrete, consider a simplified example inspired by the practices described by MRPeasy, CAI Software, Simcona, and others.

Assume you have an existing PLCŌĆæbased control system in a commercial facility that manages UPS status, transfer switches, and alarms. The PLC is modular, with an empty rack slot reserved for future expansion, reflecting SimconaŌĆÖs and Maple SystemsŌĆÖ advice to design for growth.

You plan a twoŌĆæphase upgrade. In phase one, you will add new monitoring points, requiring one digital input module and one analog input module. In phase two, scheduled eighteen months later, you will add a new power distribution section, needing one more digital module, another analog module, and a communication module to integrate with an updated monitoring platform.

Based on supplier information and MRPeasyŌĆÖs lead time categorization, you estimate the following for each module type: procurement and approval time of one week, supplier lead time of twenty weeks for digital modules, twentyŌĆæsix weeks for analog modules, and thirty weeks for communication modules, and internal installation and testing time of three weeks per modification cycle.

For phase one, your cumulative lead time is relatively straightforward. For the analog module, following the simple structure from Amper and CAI Software, you add one week of preŌĆæprocessing, twentyŌĆæsix weeks of supplier lead time, and three weeks of internal work, giving thirty weeks. For the digital module, that calculation yields one plus twenty plus three, or twentyŌĆæfour weeks. Because you need both modules to complete the upgrade, phase oneŌĆÖs effective lead time is the longer of the two, thirty weeks.

If phase one must be operational by January, you should release orders no later than the previous May. That assumes no buffer; a more conservative planner might pull that date into April to account for variability.

For phase two, you could repeat the same calculation and plan to order modules about thirtyŌĆæfour weeks ahead, given the longer communication module lead time. Alternatively, following CongerŌĆÖs and MRPeasyŌĆÖs suggestions about order sizing, you might place a single combined order for all four I/O modules and the communication module during phase one, holding the phaseŌĆætwo modules in inventory. That means enduring the long lead time once, then drawing on stocked modules later.

To decide, you compare the carrying cost of holding those phaseŌĆætwo modules for eighteen months with the risk and cost of a delayed phaseŌĆætwo upgrade if lead times stretch or allocations worsen. MRPeasyŌĆÖs observation that supply disruptions cost roughly eight percent of revenue gives a reference point: the cost of a few extra PLC modules is usually negligible compared with even a small fraction of revenue loss from delayed facility capacity or service availability.

By running this simple exercise up front, you turn vague worries about ŌĆ£long PLC lead timesŌĆØ into an explicit, quantified plan. You also create clear last responsible order dates and can build supplier agreements, internal approvals, and project milestones around them.

MRPeasy and Simcona indicate that electronic and PLC components can sit in the twelve to forty week range, with some PLC families reaching a year. A practical rule is to work backward from your required inŌĆæservice date, include realistic preŌĆæprocessing and internal installation time, and then add a buffer to account for variability. In many power projects today, ordering core PLC expansion modules six to nine months ahead of when you need them is not excessive; in fact, it is often necessary.

Maple Systems, Simcona, and Plant Automation Technology all emphasize scalability, compatibility, and futureŌĆæproofing. Oversizing the base PLC and I/O can reduce dependence on future expansion modules but raises upfront cost and risks unused or obsolete capacity. Relying heavily on expansion modules keeps initial cost lower and aligns with modular design but exposes you to long lead times. For critical power systems, a balanced approach is often best: choose a modular PLC, leave rack space for expansion, size CPU and memory for growth, and then mitigate expansion lead time with strategic spares and supplier agreements.

Lead time and disruption data from MRPeasy and the broader supply chain literature are your allies. When raw material delivery times have increased by around twentyŌĆæfive percent and supply disruptions cost manufacturers roughly eight percent of revenue, the expense of carrying a handful of critical PLC modules is tiny by comparison. Frame spare expansion modules as an insurance policy against delayed capacity and lost revenue, backed by documented lead times and business impact if key power upgrades slip.

In power systems, you do not get credit for the expansions you designed, only for the ones you actually deliver. Treat PLC expansion modules as a leadŌĆætime and reliability problem from day one, and you can build UPS, inverter, and power protection projects that scale on your schedule, not on the component marketŌĆÖs.

Leave Your Comment