-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

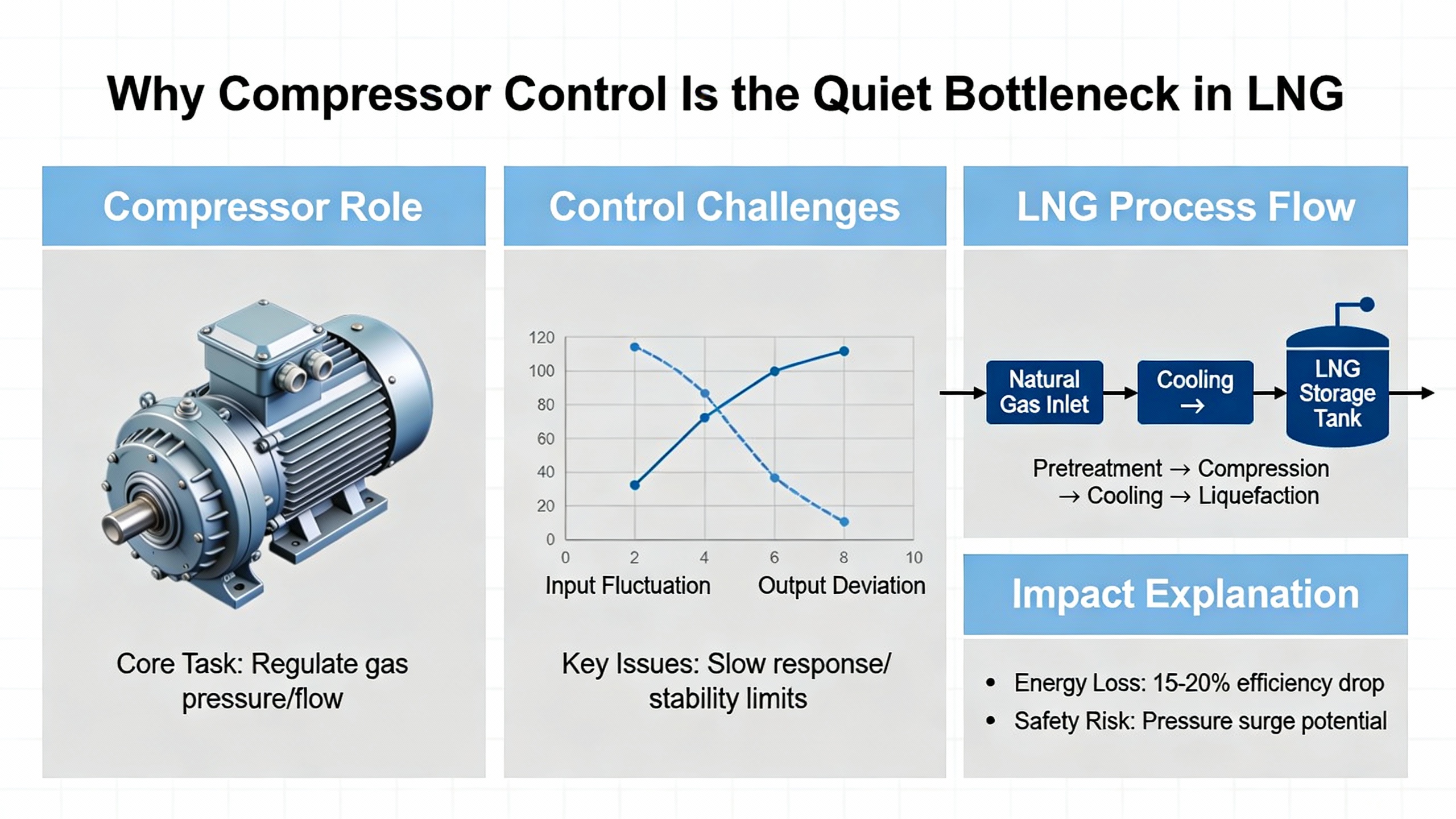

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is one of the fastestŌĆægrowing segments of the gas market, with trade growing steadily over the last decade as utilities and industries search for lowerŌĆæcarbon fuels. Turning gas into LNG and back again is, however, brutally energyŌĆæ and capitalŌĆæintensive. A large share of that intensity sits inside compressor trains.

Across gas operations, compression can account for up to about half of total energy consumption according to analysis shared by Detechtion. In LNG specifically, research on liquefaction cycles shows that the liquefaction step alone can consume around 30% of the total energy required to get LNG from wellhead to burner tip. If your compressor trains and their control systems are not designed and tuned properly, you are effectively leaving throughput, efficiency, and reliability on the table every minute the plant runs.

From a power systems and reliability standpoint, compressors are a double criticality. They draw large, often continuous electrical loads, and their controls depend on clean, uninterrupted auxiliary power. A nuisance trip on a boilŌĆæoff gas compressor or a turboŌĆæexpanderŌĆædriven compander might be rooted in poor control logic or a sluggish antiŌĆæsurge valve, but its consequences are felt in the electrical room as sudden load swings, protection operations, and sometimes blackouts in islanded terminals.

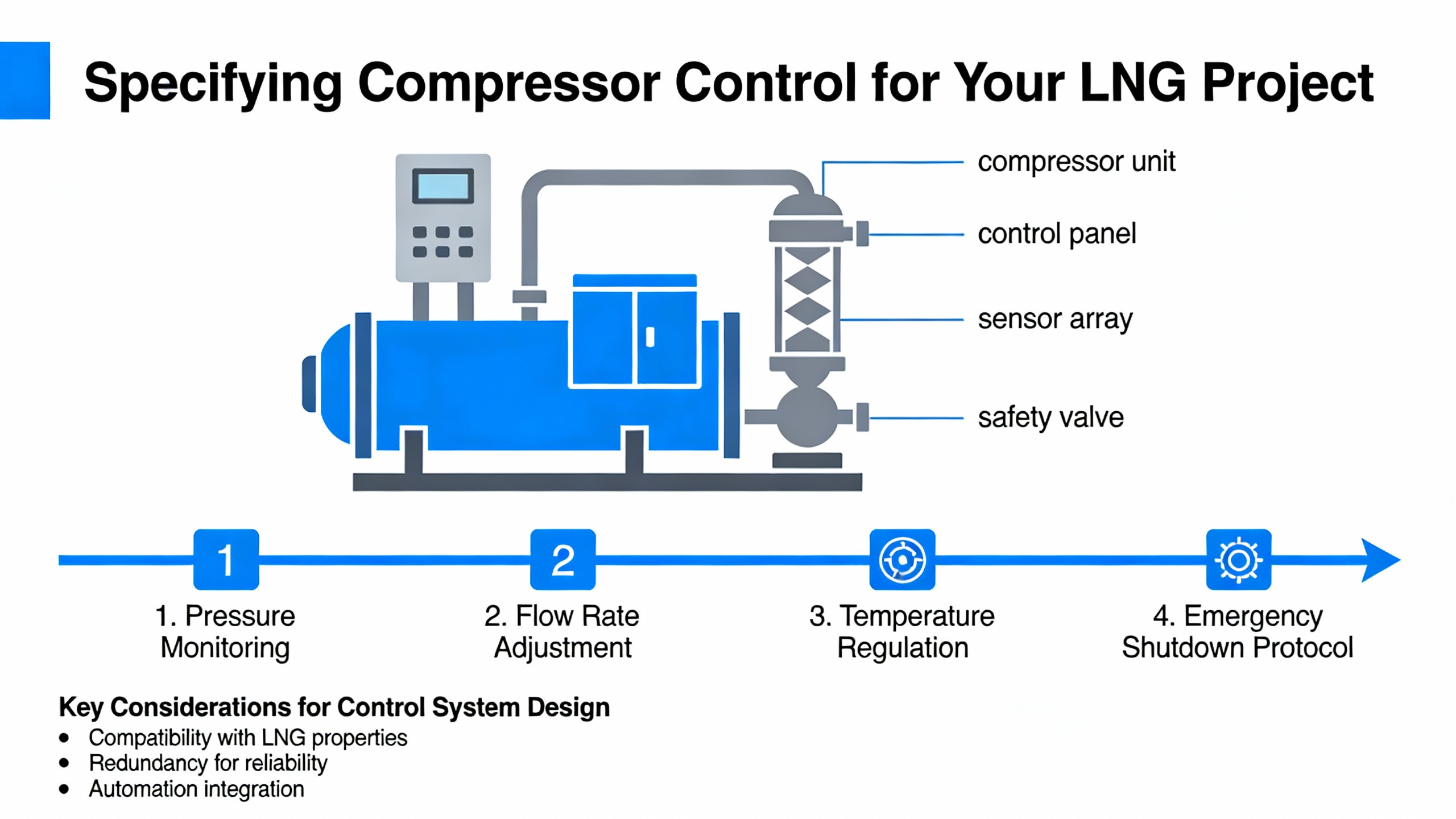

This article looks at compressor control systems for LNG facilities from a combined process and powerŌĆæreliability perspective. Drawing on realŌĆæworld cases and studies from LNG industry specialists, automation vendors, and compressor OEMs, the goal is to help you answer three practical questions:

How should we select and control our compressors across the LNG value chain? How can advanced control, surge protection, and digital monitoring safely stretch capacity and reduce energy use? How do we keep these control systems and their power supplies reliable over a twentyŌĆæplusŌĆæyear asset life?

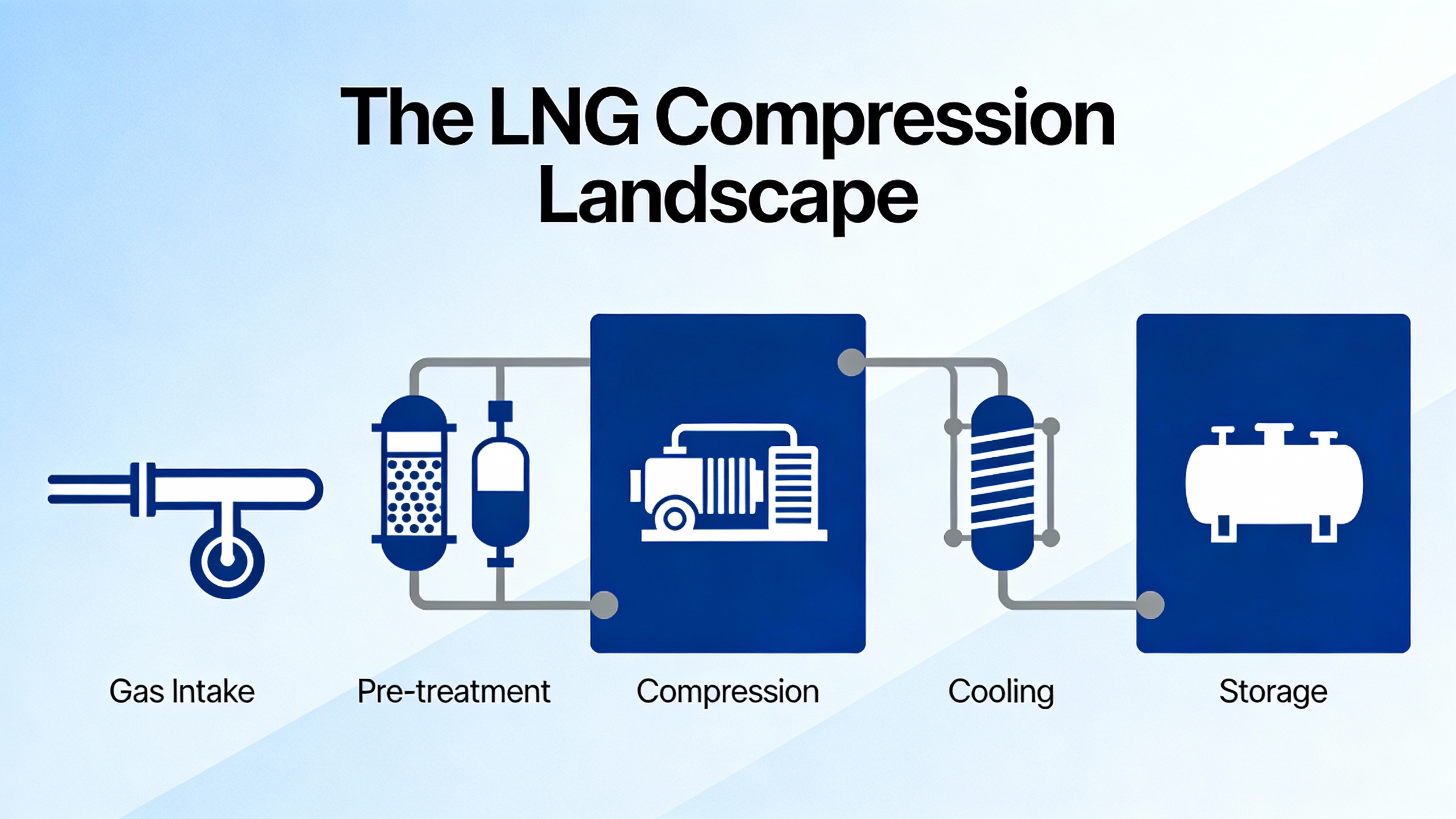

Compressors touch almost every stage of the LNG chain. China Compressors and Detechtion both emphasize that compression is essential upstream to pressurize gas for treatment, in midstream pipelines and storage, and downstream in LNG processing, shipping, and regasification.

In and around the liquefaction train, compressors raise feed gas pressure to thermodynamically favorable levels, drive mixedŌĆærefrigerant cycles or nitrogen Brayton cycles, and keep the refrigeration loop moving. Centrifugal machines are typically preferred here because they handle very high, steady flow rates efficiently, which aligns with LNG ŌĆ£mega trainŌĆØ throughputs described by LNG Industry and Severn Valve.

At LNG terminals, oilŌĆæfree reciprocating compressors handle boilŌĆæoff gas (BOG) generated when cryogenic LNG warms slightly in tanks, pipelines, and loading arms. Engineer News Network documents how BurckhardtŌĆÖs oilŌĆæfree compressors manage BOG down at cryogenic inlet temperatures around minus 274┬░F, compressing it for reŌĆæliquefaction or burning as fuel. Without this service, you would either vent or flare valuable gas and emissions would rise sharply.

On the regasification side, Emerson notes that BOG compressors, lowŌĆæpressure sendŌĆæout boosters, and sometimes screw compressors are coordinated to match sendŌĆæout flow with grid nominations. Here, control quality directly affects the ability to operate close to storage, pipeline, and safety constraints without trips.

Several sources, including Detechtion and China Compressors, converge on three primary compressor types in LNG: reciprocating, centrifugal, and screw units. A fourth category, compander packages, integrates a compressor and turboexpander for compact smallŌĆæscale liquefaction.

A concise view of their roles is useful when you start thinking about control strategy:

| Compressor type | Typical LNG role | Strengths | Limitations relevant to control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reciprocating (piston) | BOG handling, fuel gas boosting, smallŌĆæscale liquefaction stages | High pressure ratios, flexible turndown, precise capacity control, proven oilŌĆæfree designs | Many moving parts; pulsating flow; requires pulsation control and robust foundations |

| Centrifugal (dynamic) | Main refrigerant and feed gas compression in large trains; highŌĆæcapacity BOG service | High flow, relatively low maintenance, smooth flow | Narrow stable range; strong surge behavior; requires fast, accurate antiŌĆæsurge control |

| Screw (rotary) | MediumŌĆæscale distribution and regasification steps | Smooth flow, good for wet/dirty gas, relatively simple controls | SingleŌĆæstage discharge pressure typically limited; efficiency sensitive to offŌĆædesign operation |

| Compander (integrated compressorŌĆōexpander) | SmallŌĆæscale nitrogenŌĆæcycle liquefaction | Compact footprint, shared auxiliaries, lower leakage and CAPEX | Specialized equipment; control interaction between compressor and expander must be carefully engineered |

Atlas CopcoŌĆÖs work on compander technology in smallŌĆæscale LNG plants shows how integrating a centrifugal compressor and turboexpander on a single gearbox and skid can shrink footprint, reduce piping and cabling, and cut capital cost. Because the compressor and expander share lube and seal systems and often share controls, you also reduce the number of interfaces that can fail. That compactness, however, raises the bar for the control system and its power supply, because any commonŌĆæmode failure affects both cold generation and compression.

The control takeaway is that each compressor type comes with predictable dynamic behavior and mechanical limits. Reciprocating units demand careful valve condition monitoring and pulsation control. Centrifugals demand technically sophisticated surge protection. Screws and companders require attention to efficiency at part load. A robust compressor control strategy begins by honestly aligning these characteristics with your process objectives and your plantŌĆÖs power system capabilities.

Severn Valve describes centrifugal compressor surge in LNG trains as a dynamic instability where flow falls below what is needed to overcome discharge pressure. Flow reverses, pressure and flow oscillate, and the surge cycle can repeat indefinitely without intervention. Surge and stall events occur extremely fast, on the order of 20 to 50 milliseconds.

Those time scales explain why simply relying on a DCS loop with a modestly tuned PID is not enough. Surge can damage seals, bearings, impellers, and shafts. Severn notes that seal damage alone can cost tens of thousands of dollars, and severe events can force an emergency trip of the entire liquefaction train, with production losses in the tens of millions of dollars.

Historically, many LNG plants protected themselves by operating compressors far from the surge line, leaving a wide safety margin. Severn reports that for large trains with antiŌĆæsurge valves (ASVs) traveling more than 18 inches, conservative strategies were often the only way to cope with actuation limits. The price was reduced throughput and significantly lower energy efficiency.

Modern antiŌĆæsurge valves and actuators change that tradeoff. SevernŌĆÖs latest largeŌĆæbore antiŌĆæsurge valves, including a 30ŌĆæinch bore valve with a 24ŌĆæinch stroke, can move through full travel in less than two seconds while maintaining very fine positional control. EmersonŌĆÖs guidance on highŌĆæintegrity valve and actuator assemblies for BOG compressors echoes this: the valve, actuator, and digital controller must work as a tuned system to detect approaching surge and open fast enough to keep the compressor on the safe side of its map.

From a control perspective, good surge control is not just about speed. It is about accurate position sensing, repeatable stroking, correct valve sizing (often 1.8 to 2.2 times expected maximum surge flow as Severn describes), clean instrument power, and tested logic. If your control power is unstable, your positioner calibration is drifting, or your solenoid valves stick, your twoŌĆæsecond requirement may suddenly be four seconds right when you can least afford it.

DetechtionŌĆÖs analysis across gas assets shows that compression can absorb up to roughly half of total energy use. LNGŌĆæspecific research on boilŌĆæoff gas modeling highlights that compressing gas requires about ten times as much energy as pumping an equivalent mass of liquid. Every percentage point of compressor efficiency you recover is therefore worth chasing, both in operating cost and in environmental footprint.

Consider a plant with a main refrigerant compressor driven by a 30,000ŌĆæhorsepower motor and BOG compressors totaling another 10,000 horsepower. If advanced control, better antiŌĆæsurge tuning, and predictive maintenance reduce overall compressor power by just 3%, you save roughly 1,200 horsepower, or close to 900 kW of electrical demand. Over a year of highŌĆæload operation, that is measured in millions of kilowattŌĆæhours and a sizeable reduction in emissions.

On the power systems side, these loads drive transformer sizing, mediumŌĆævoltage distribution, harmonic filtering, and backup generation where plants run islanded. WunderlichŌĆæMalecŌĆÖs case study of an islanded LNG terminal illustrates how fragile such a system can be when the turbineŌĆægenerator controls and hydraulic actuators are unreliable. Spurious trips of the single generator caused repeated shutdowns and productivity loss. Upgrading to a modern digital turbine control system with redundant overspeed protection, highŌĆæreliability hydraulic actuators, and onlineŌĆætestable protection preserved power availability and made the entire terminal more resilient.

For compressor control, the lesson is twofold. First, good process control on compressors directly influences how much power you draw. Second, the power system and control power infrastructure must be designed so that compressors and their controls ride through transients without nuisance trips. That often means dedicated UPS support for critical controllers and positioners, wellŌĆæengineered grounding, and coordination between electrical protection settings and process control strategies.

At the lowest level, compressor trains rely on regulatory loops to hold pressures, flows, and temperatures. Discharge pressure controllers modulate recycle valves or guide vanes, suction controllers manage upstream valves, and temperature loops adjust refrigerant flows. These loops run in the DCS or a dedicated compressor control system.

Safety functions such as overspeed protection, highŌĆæhigh temperature shutdowns, and emergency trips are typically implemented in separate protection systems. In LNG, integrated control and safety systems (ICSS) from vendors such as Honeywell and Yokogawa are now common, especially onshore. Opero Energy notes that ICSS platforms combine process control and safety instrumented functions on a unified architecture, which simplifies integration across compression, pipelines, tank farms, and regasification units.

Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs LNG project experience emphasizes that design tools, modular control buildings, and cloudŌĆæbased testing can deŌĆærisk ICSS deployment. PreŌĆæinstalled and preŌĆætested control systems in prefabricated electrical buildings allow compressor controls, antiŌĆæsurge logic, and electrical protection to be validated offsite before commissioning. For the power system specialist, that modularization is an opportunity to verify control power segregation, UPS autonomy, and failŌĆæsafe behavior under simulated lossŌĆæofŌĆæpower events.

Three Severn Valve technical pieces make a consistent argument: antiŌĆæsurge valves should be specified and tested as complete engineered packages, not commodity control valves. In LNG trains, large valves with strokes of up to 24 inches must open very quickly and stop precisely to avoid both surge and unnecessary recycle.

To achieve that, Severn integrates bespoke valve trim for accurate pressure letdown with highŌĆæpower piston actuators, suitable boosters, and digital positioners. Each assembly is fully calibrated and verified with an independently calibrated test system that measures response against antiŌĆæsurge specifications. The result is a valve that can complete a full stroke in under two seconds while still offering fine throttling around the operating point.

Emerson similarly recommends highŌĆæintegrity antiŌĆæsurge valve assemblies for BOG compressors, integrating valve, actuator, and diagnostics. When these assemblies are tied into advanced process control (APC) applications in the DCS, BOG compressors can run closer to constraints, with fewer trips and less flaring.

This is also where clean, reliable power matters. HighŌĆæpower actuators and digital positioners draw impulsive currents and are sensitive to voltage dips. Feeding them from properly sized power circuits with adequate rideŌĆæthrough capability, combined with UPSŌĆæbacked control power, is essential. The most sophisticated antiŌĆæsurge algorithm is useless if a brief voltage sag leaves the actuator stranded midŌĆæstroke.

The WunderlichŌĆæMalec case study highlights an LNG terminal where a single turbineŌĆægenerator provided all site power, making the turbine control system a single point of failure. Problems with hydraulic actuator performance, limited diagnostics, and poor integration with the plant DCS led to frequent trips.

Upgrading to a modern digital control system (Woodward MicroNet Plus) with redundant overspeed detection (ProTech TPS), highŌĆæreliability hydraulic actuators, and a wellŌĆæintegrated HMI improved situational awareness and allowed online testing of protection functions. Importantly, the new control system provided clear trip reasons, which enabled maintenance teams to correct root causes rather than simply restarting the unit.

For LNG compressor trains, a similar philosophy applies. Speed control, generator load control, and steam or fuel gas pressure control all interact with compressor loading. Coordination between generator control, motor starting schemes, softŌĆæstarters or VFDs, and compressor capacity control loops reduces electrical and mechanical stress. Protection systems must be coordinated so that electrical faults, mechanical faults, and process faults are distinguished and acted upon appropriately, rather than causing unnecessary plantŌĆæwide shutdowns.

LNG IndustryŌĆÖs examination of advanced control and optimization in LNG plants identifies three major challenges: rapidly changing inlet conditions, tight coupling between process units, and shifting equipment and ambient constraints. Basic control can keep compressors and associated towers stable, but it tends to be conservative, leaving substantial inefficiencies in energy use and capacity.

Advanced Process Control (APC), especially multivariable model predictive control (MPC), handles these interactions more intelligently. APC coordinates multiple setpoints and manipulated variables simultaneously, predicting process behavior and moving the plant towards an economic optimum rather than a fixed operating target.

Field experience reported in LNG Industry shows APC increasing LNG processing capacity by roughly 1 to 5 percent, optimizing NGL and LPG recovery, and cutting energy and refrigerant consumption by stabilizing key temperature profiles. EmersonŌĆÖs work on regasification plants echoes this, showing that integrating APC for BOG compressors into the DCS allows operators to run closer to constraints, reduce compressor trips and flaring, and increase throughput.

Translated into a simple example, consider a 5ŌĆæmillionŌĆætonŌĆæperŌĆæyear liquefaction plant. A 2 percent capacity increase from APC and constraints management is equivalent to roughly 100,000 tons of additional LNG per year. At a modest netback, that figure easily dwarfs the cost of APC deployment and longŌĆæterm maintenance.

Advanced economic model predictive control (EMPC) can be powerful but also computationally expensive and modelŌĆæintensive. Research on selfŌĆæoptimizing control for LNG liquefaction suggests an alternative: carefully choosing combinations of measurements that, when held at fixed setpoints with conventional feedback controllers, keep the plant near its economic optimum under varying conditions.

In that study, which extended earlier work to a cascaded LNG plant with multiple refrigerant cycles, the authors applied a systematic ŌĆ£exact local methodŌĆØ to select the best measurement combinations. They incorporated measured disturbances directly into the controlled variables and used a branchŌĆæandŌĆæbound algorithm to trade off performance against control complexity. The resulting control structures exhibited lower steadyŌĆæstate economic losses and better closedŌĆæloop performance compared with conventional temperatureŌĆæbased strategies.

For plant teams, the key insight is that you do not always need a full EMPC layer to reap most of the economic benefit. By instrumenting the plant correctly, identifying robust controlled variables (for example, specific temperature differences across key heat exchangers or carefully chosen pressure ratios), and tuning the existing controllers around those variables, you can achieve nearŌĆæoptimal operation while keeping the control architecture relatively simple and robust to hardware failures.

At LNG import terminals, advanced compressor control does not operate in isolation. Emerson highlights that terminal information management systems (TIMS) and highŌĆæintegrity tank gauging are foundational. Inventory management platforms such as Rosemount TankMaster collect realŌĆætime level, temperature, density, and pressure data from LNG tanks, then compute volume and mass for accurate custody transfer and tank usage optimization.

Emerson notes that ineffective inventory and supply chain management can reduce a terminalŌĆÖs profitability by as much as 5 percent through poor cargo tracking and suboptimal jetty utilization. Accurate inventory and predictive scheduling, by contrast, allow operators to plan BOG handling and compressor operation more efficiently.

Modern tank gauging with nonŌĆæcontact radar can measure levels in tanks over about 130 feet high, with measurement ranges around 180 feet. With no moving parts and mean time between failures measured in decades, these systems provide reliable data even when maintenance access is limited. APC and scheduling tools then use this highŌĆæintegrity data to coordinate compressor setpoints, ship unloading, and sendŌĆæout rates.

From a power and reliability perspective, tank gauging, TIMS servers, and compressor controls are all critical loads that benefit from UPS support and redundant network paths. If your tank gauging goes blind during a power disturbance, you may be forced into conservative operation or even shutdowns until you can verify inventory, no matter how robust your compressor controls are.

Research on LNG terminal operation shows that LNG is stored at about minus 260┬░F, with volume reduced to roughly oneŌĆæsixŌĆæhundredth of its gaseous state. Despite good insulation, heat ingress generates BOG and causes tank pressure to rise. Because compression of gas is about ten times more energyŌĆæintensive than pumping the same mass of LNG, BOG handling strategy is one of the most important levers for terminal operating cost.

Detailed numerical simulations of large tanks demonstrate that the boilŌĆæoff rate (BOR) is very sensitive to fill level. At high fill levels around 80 percent, BOR may be near 0.012 weight percent per day, while at low fill levels around 10 percent, BOR can climb to roughly 0.12 weight percent per day, an orderŌĆæofŌĆæmagnitude increase. For a terminal discharging on the order of 80,000 cubic meters per day, about 2.8 million cubic feet per day, that difference translates into substantial additional gas that must be compressed or burned.

The same study shows that optimized delivery scheduling and sendŌĆæout control can reduce BOG generation by around 9 percent compared with conventional strategies, without major new hardware. That reduction directly cuts HP compressor run time and power consumption.

When BOG cannot be recondensed via cold LNG or dedicated heat exchangers, highŌĆæpressure compressors must handle it and send it to the sendŌĆæout pipeline. These HP compressors are costly to operate, especially at partial loads, and often become bottlenecks.

The numerical BOG model research proposes a sendŌĆæout control strategy that minimizes HP compressor operating cost. At high sendŌĆæout rates, it is economically favorable to reduce LNG recirculation and accept more BOG inflow, because the sendŌĆæout system can absorb the additional gas without overloading the HP compressors. At low sendŌĆæout rates, by contrast, increasing LNG recirculation and lowering BOG inflow can keep BOG within manageable limits, reducing the need to run HP compressors in inefficient regimes.

If your control system can accurately predict BOG generation based on tank levels, heat ingress, and operating conditions, you can schedule compressors and adjust sendŌĆæout targets to minimize the time HP compressors spend in expensive highŌĆæhead, lowŌĆæflow conditions. That is where they draw the most power and suffer the greatest mechanical stress.

Engineer News Network presents several case studies where targeted upgrades and condition monitoring delivered large reliability gains for BOG compressors. At one LNG terminal, perlite insulation debris caused abrasive wear and poor performance of rider rings, leading to frequent piston replacements and ring changes every roughly 8,000 operating hours. A tailored upgrade with an aluminum firstŌĆæstage piston, dryŌĆærunning optimized rider rings, a coated piston rod, new cylinder liner, and improved sealing materials raised mean time between overhaul from about 8,000 hours to over 24,000 hours, with higher lifetimes on later stages.

In another case, a terminal was flaring gas for up to an hour at each compressor start due to frequent starts and slow gas cooling. Investigation found that the desuperheater was being bypassed during startup, underutilizing the first cooling step. Process changes, including revised startup sequences, running the compressor in bypass while using the desuperheater, and upgrading components such as packing and bearings, were projected to cut flaringŌĆærelated emissions by around 25 tons of COŌéé equivalent per year.

Across these examples, API 670ŌĆæguided monitoring with vibration, crankŌĆæangle, and accelerometer sensors was crucial in detecting clearance issues, valve faults, and gas leaks. Using this data for structured programs such as BurckhardtŌĆÖs BC ACTIVATE and longŌĆæterm service agreements allowed the operators to move from reactive maintenance to a more predictive, lifecycleŌĆæoriented approach.

When you combine such mechanical and materials upgrades with smarter operating strategies and accurate BOG modeling, you reduce both energy consumption and unplanned downtime of HP compressors. From a power system perspective, fewer unplanned compressor starts and trips also means less stress on feeders, breakers, and UPS systems.

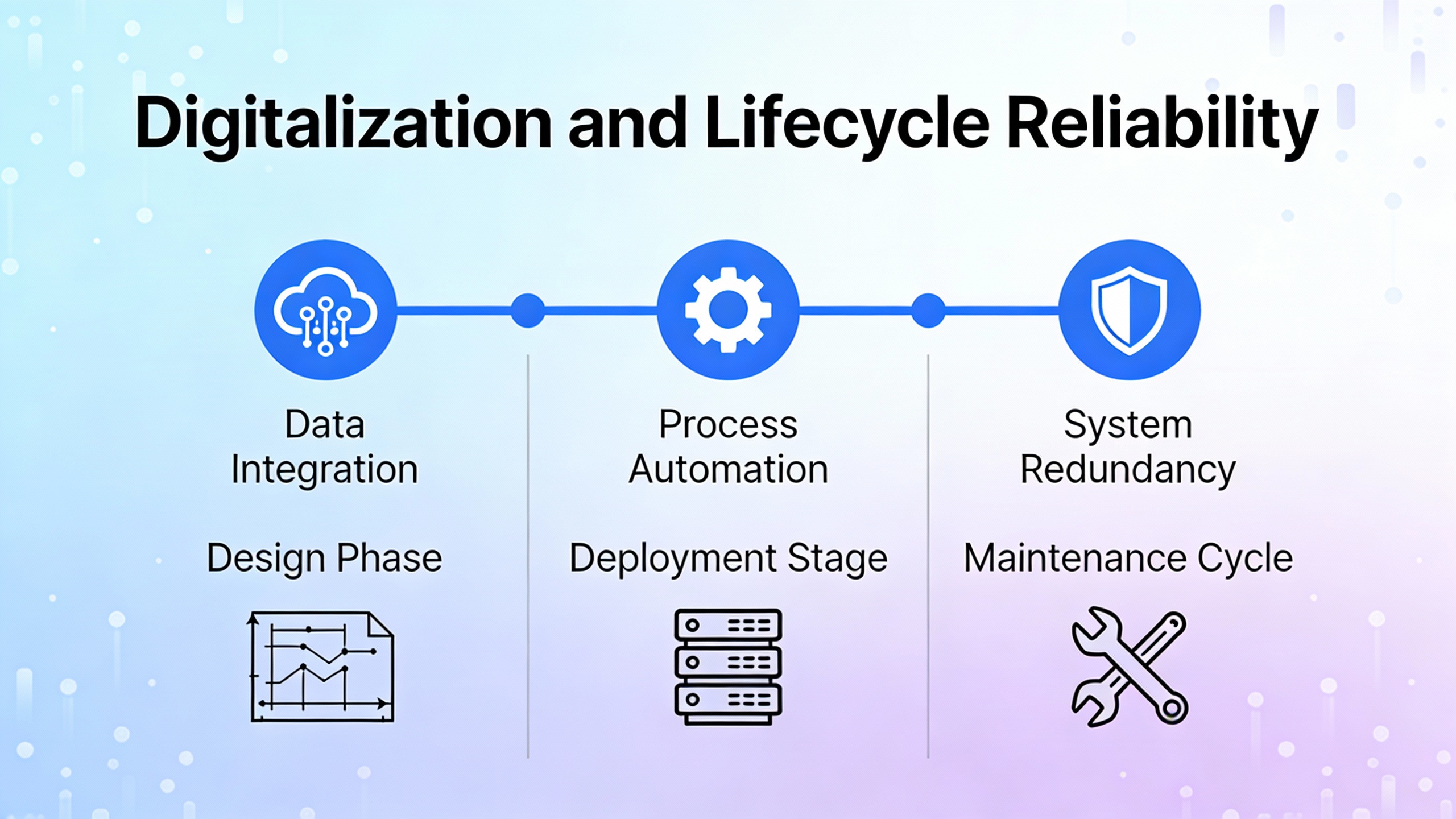

Detechtion reports that preventive and predictive maintenance programs can deliver roughly 10 to 20 percent reductions in compressorŌĆærelated energy costs by maintaining efficiency and reducing unplanned shutdowns. EmersonŌĆÖs Plantweb digital ecosystem shows how this plays out in LNG terminals: intelligent field devices, advanced sensors, and analytics software aggregate equipment health data into userŌĆæfriendly dashboards, feeding machine learning tools that detect abnormal behavior and predict future issues.

For compressors, this means continuous monitoring of vibration, temperatures, bearing condition, lubrication quality, and thermal performance of associated heat exchangers. Emerson notes that 24/7 monitoring of assets such as heat exchangers can detect fouling early, allowing planned cleaning that improves energy efficiency, unit utilization, and throughput while avoiding emergency shutdowns.

FSŌĆæElliottŌĆÖs PAP Plus compressor line illustrates how compressor OEMs are embedding digitalization. Their Regulus control system not only provides advanced flow and pressure control but also includes an Energy Advisor module that analyzes realŌĆætime data to recommend energyŌĆæsaving settings. A predictive maintenance module monitors wear indicators and thermal performance to issue early service notifications. WebŌĆæbased remote monitoring ties these elements into plantŌĆæwide digital initiatives.

For a power system and reliability team, the connection is straightforward. Every avoided compressor trip reduces the chance of large reactive power swings, motor restarts, and cascading protection operations. Instrumenting compressors and their power feeds, and then using that data proactively, turns a large, spiky electrical load into a more predictable and manageable one.

Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs LNG automation work emphasizes that digitization, modularization, and simplification are the three themes that reduce risk from design through operation. Integrated digital engineering tools replace siloed design, enabling collaborative modeling of compressors, power systems, and controls. CloudŌĆæbased engineering and testing can replicate entire automation systems so that control logic for compressors, antiŌĆæsurge valves, and power distribution can be developed and tested remotely.

Opero Energy notes that major vendors now routinely deploy ICSS platforms that integrate process and safety functions for LNG plants. In many cases, compressor controls, electrical protection, and fire and gas systems are all accessible through a central control room, with data from sensors, gas monitors, and closedŌĆæcircuit television systems feeding into the same operator interfaces.

For owners and EPCs, this means compressor control system specifications should be written with lifecycle support and digital integration in mind. Questions worth asking early include whether compressor controls and motor protection will be integrated into the ICSS, how compressor trips will be logged and diagnosed, how cyberŌĆæsecurity will be handled for remote monitoring, and how control power for critical components will be backed up and segregated to avoid commonŌĆæmode failures.

WunderlichŌĆæMalecŌĆÖs rotating machinery controls upgrade at an islanded LNG import/export terminal provides a concrete illustration of an integrated approach. The facility relied on a single turbineŌĆægenerator for all power. The original OEM turbine controls suffered from unreliable hydraulic actuators, poor diagnostics, and lack of integration with the DCS, leading to monthly unplanned trips.

The upgrade introduced a modern digital control system with primary and expansion I/O racks, highŌĆæpressure hydraulic actuators with redundant servos and feedback, and a separate overspeed protection system. Operator interfaces were improved with a modern HMI and Modbus TCP integration to the DCS. Extensive factory testing using a hardwareŌĆæbased turbine simulator and turnkey hydraulic and mechanical installation ensured the system worked as intended.

While the case focuses on the power train, the same philosophy applies to LNG compressor control upgrades. Integrate new control logic with plant DCS and ICSS. Use simulation and factory testing to validate antiŌĆæsurge behavior and trip logic. Upgrade actuators, positioners, and feedback elements, then power them from robust, UPSŌĆæbacked supplies. Finally, ensure that operators and maintenance staff understand trip causes and can interpret diagnostic data rather than treating every shutdown as a mystery.

When you look across these studies and case examples, several practical themes emerge for specifying compressor controls in LNG facilities, especially if you are responsible for both process performance and power system reliability.

First, align compressor type and control strategy with the specific duty. Reciprocating BOG compressors benefit from oilŌĆæfree designs, robust valve monitoring, and conditionŌĆæbased materials upgrades to extend overhaul intervals, as demonstrated in BurckhardtŌĆÖs case studies. Main liquefaction compressors, typically centrifugal, demand highly engineered antiŌĆæsurge valves, modern MPCŌĆæbased control of recycle and guide vanes, and careful coordination with electrical starting and protection systems.

Second, explicitly integrate energy efficiency into your control objectives. Compression is a dominant share of your electrical load. Evidence from LNG Industry and Detechtion suggests that 1 to 5 percent capacity improvements and 10 to 20 percent energy savings are realistic with wellŌĆæimplemented APC and predictive maintenance. On a large train with tens of megawatts of compressor load, even the lower end of those ranges can justify investment in advanced controls and highŌĆæintegrity instrumentation.

Third, treat antiŌĆæsurge and HP BOG compression as highŌĆæconsequence services and design their controls and power supplies accordingly. Specify valves and actuators as complete, tested packages with documented stroke times and positional accuracy. Feed critical controllers and positioners from reliable, monitored UPS systems with sufficient rideŌĆæthrough for realistic disturbance scenarios. Test surge logic using dynamic simulation of compressor maps and process upsets before going live.

Fourth, use digital tools and models to manage BOG and HP compressor operation holistically. Numerical BOG models and TIMS platforms make it practical to schedule ships, manage tank fill levels, and adjust sendŌĆæout rates in ways that reduce BOR and HP compressor run time by meaningful percentages. EmersonŌĆÖs and the numerical modelŌĆÖs findings show that better scheduling alone can cut BOG and associated compressor operation by close to 10 percent in some terminals.

Finally, think in terms of lifecycle partnerships rather than oneŌĆæoff projects. Programs like BurckhardtŌĆÖs BC ACTIVATE and longŌĆæterm service agreements with compressor, valve, and control OEMs provide structured paths for continuous improvement. When combined with asset performance software and remote monitoring, they give you an ongoing stream of data and expertise to refine control strategies, component selections, and maintenance schedules as your plant ages and operating conditions evolve.

Evidence from LNG Industry and Emerson indicates that both large and midŌĆæscale plants benefit from advanced control. In large trains, a 1 to 5 percent capacity increase translates into very large absolute LNG volumes and revenue. In smaller plants, compander technology and efficient BOG management can significantly lower operating costs and improve competitiveness in tight markets. Because compressor power is such a large part of the energy bill in any LNG facility, even modest efficiency gains from better control and scheduling are worthwhile.

Compressors are among the largest continuous electrical loads in LNG plants. Poor surge control, frequent trips, or inefficient partŌĆæload operation lead not only to energy waste but also to voltage dips, thermal stress on transformers and switchgear, and potential instability in islanded systems. Case studies such as the islanded LNG terminal upgraded by WunderlichŌĆæMalec show that improving turbineŌĆægenerator and compressor controls together yields better availability and more stable power. WellŌĆædesigned UPS systems for control power and careful coordination of electrical protection with process trips are key elements of that integration.

LNG IndustryŌĆÖs field experience and EmersonŌĆÖs regasification work suggest that APC and modelŌĆæbased compressor coordination can deliver roughly 1 to 5 percent increases in LNG capacity, reductions in BOG compressor trips, and measurable decreases in flaring and fuel use. DetechtionŌĆÖs broader gas compressor analytics show 10 to 20 percent reductions in compressorŌĆærelated energy costs in some programs that combine operating optimization and predictive maintenance. The exact benefit for your facility will depend on current performance and constraints, but these ranges provide a credible expectation for wellŌĆæexecuted projects.

For LNG facilities, compressor controls sit at the intersection of thermodynamics, rotating machinery, and power system reliability. When they are engineered, powered, and maintained as critical infrastructure, they unlock higher throughput, lower energy use, and fewer unplanned outages. When they are treated as an afterthought, they quietly cap capacity and erode margins.

From a power system specialist and reliability perspective, the most effective path forward is to view compressor controls, surge protection, BOG management, and control power as a single integrated design problem. Plants that make that integration a priority are the ones that will keep their trains, terminals, and balance sheets running smoothly in the years ahead.

| Source / Publisher | Relevance to compressor control in LNG |

|---|---|

| Detechtion | Natural gas compressor types, energy share, optimization, and maintenance practices |

| Schneider Electric | LNG automation project risks, integrated automation and electrification, digital engineering |

| Opero Energy | Automation roles and ICSS in LNG plants |

| China Compressors | LNG compressor types, selection criteria, and efficiency considerations |

| Emerson | Advanced automation for LNG regasification, TIMS, tank gauging, APC for BOG compressors, predictive maintenance |

| LNG Industry | Advanced process control and optimization impacts on LNG plant performance |

| Atlas Copco Gas and Process | Compander technology for smallŌĆæscale LNG, efficiency and CAPEX reduction |

| Engineer News Network | BOG compressor roles, case studies on upgrades, API 670 monitoring, lifecycle programs |

| FSŌĆæElliott | Centrifugal compressor design and digital control (Regulus) for LNG environments |

| Severn Valve | AntiŌĆæsurge valve design, surge control challenges, and LNG compressor protection |

| WunderlichŌĆæMalec | Rotating machinery control system upgrade at an LNG import/export terminal |

| ScienceDirect studies on LNG | BOG modeling and operational strategies, selfŌĆæoptimizing control, SMR process efficiency and exergy analysis |

Leave Your Comment