-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Legacy PLCs sit quietly behind your switchgear, UPS, and inverter controls, making thousands of decisions a second that your operators never see. When they are twenty or thirty years old, that ŌĆ£quietŌĆØ becomes dangerous. Parts disappear, Windows 7 engineering laptops are kept alive like museum pieces, and a single failed CPU can suddenly take out a critical UPS-backed bus.

From a power system reliability standpoint, upgrading those legacy PLCs to modern platforms is no longer just an IT or controls project. It is a core risk-control measure for your power distribution, UPS, and power protection systems. This article walks through the main upgrade alternatives, how to choose among them, and practical tactics to migrate with minimal downtime and maximum safety.

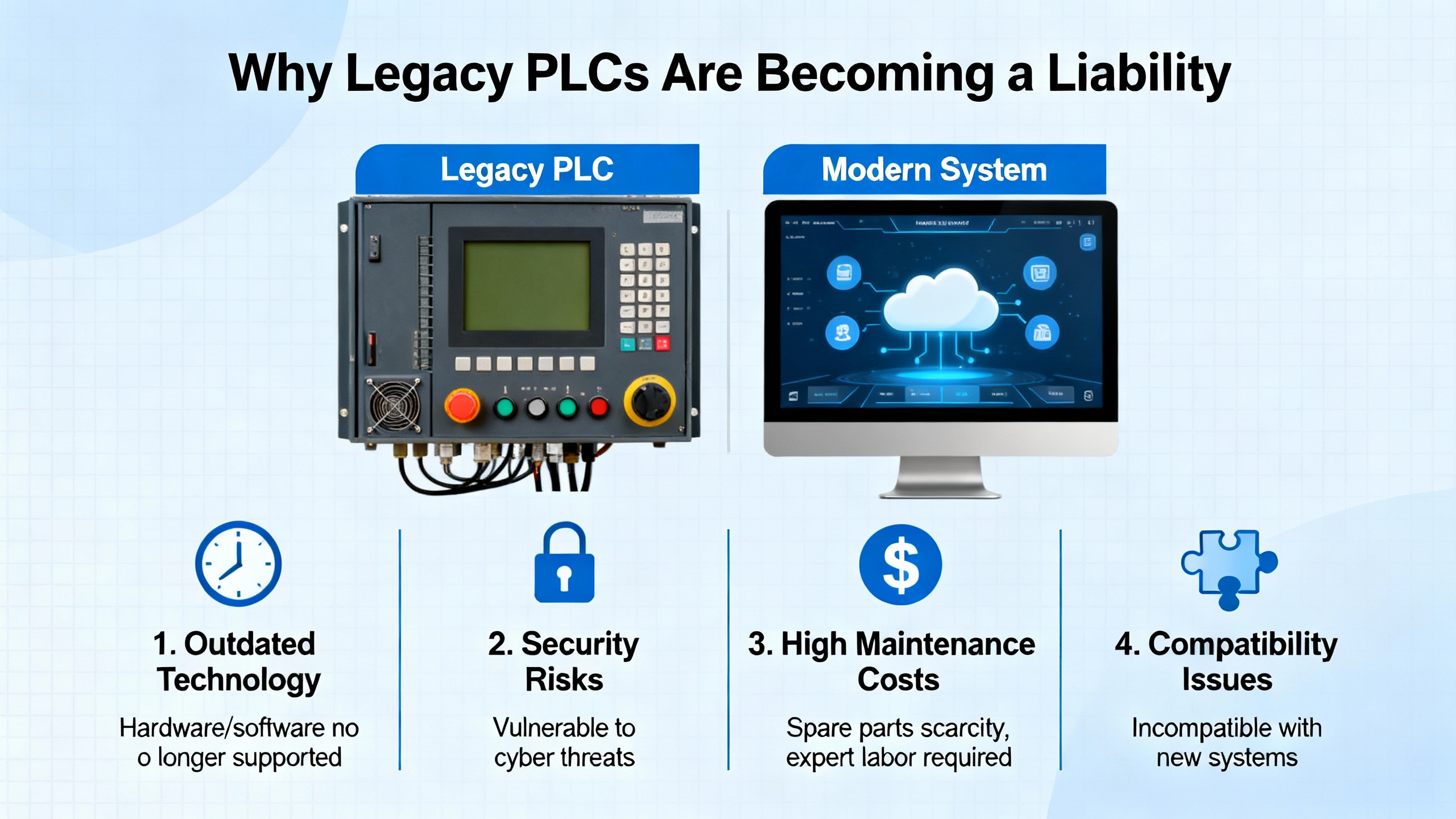

A legacy PLC system is simply a control platform whose hardware or software is no longer current or fully supported but is still in service. Across manufacturing and energy, more than half of facilities are running PLCs older than a decade, and unplanned downtime tied to aging automation contributes to an estimated $50 billion in annual manufacturing losses, with around 800 hours of lost productivity per year. Those figures, reported by industrial automation specialists, are sobering if your PLCs coordinate emergency generators, static transfer switches, or large inverters feeding mission-critical loads.

Modern articles from automation suppliers and engineering firms consistently highlight several converging issues.

Obsolete hardware and software mean that vendors have ended normal lifecycle support. Platforms such as older Siemens families or Rockwell PLC-5 and SLC-500 series are at or beyond end-of-life. Applied Manufacturing Technologies notes that controllers using RSLogix 5 or 500 and networks like DH+ and DeviceNet no longer receive firmware updates, and parts are increasingly difficult to source. Other integrators describe situations where discontinued AllenŌĆæBradley PLC-5 hardware leaves plants reliant on expensive gray-market spares.

Rising failure risk and downtime follow. As ISD Automation points out, older PLCs exhibit more frequent fault messages, nuisance trips, and unexplained shutdowns, while maintenance crews spend more time patching around failing components. In high-speed manufacturing, downtime can cost up to $22,000 per minute in some automotive operations. Even if your facility does not run at those margins, a thirty-minute outage on a UPS-backed distribution bus can easily translate into hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost production, restart scrap, and emergency response.

The cyber risk profile is also changing. Legacy PLCs and engineering stations that run on unsupported operating systems like Windows 7 no longer receive security patches. Lafayette Engineering stresses that such systems are highly exposed, especially when connected over legacy serial links and unsegmented networks. ISD cites data showing that roughly seventy percent of ransomware attacks target manufacturing across dozens of subsectors. Modern control system articles from consulting engineers emphasize that updated platforms support stronger security controls, including encrypted communications and better access management, which older systems often cannot provide.

Finally, legacy PLCs do not integrate cleanly with the data and analytics expectations of modern operations. Many older controllers lack Ethernet-based protocols like Ethernet/IP or OPC UA and have insufficient CPU power, memory, or storage for real-time data logging. ISD Automation references industry research indicating that real-time data access can improve production efficiency by up to twenty percent, yet many plants cannot fully tap that benefit because their control layer cannot connect to analytics, cloud platforms, or modern SCADA.

For critical power systems, this all compounds. A legacy PLC that supervises generator start sequences, closed-transition switching, or inverter bypass is not just another component; it is a single point of failure in your power protection chain. When its replacement CPU becomes unavailable, the ŌĆ£run it until it diesŌĆØ strategy stops being thrifty and becomes reckless.

When you decide to act, the natural question is how far to go. Industry guidance from Panelmatic, Balaji Switchgears, Control Engineering, and others describes several broad strategies for dealing with legacy PLC systems. They differ in risk, cost, downtime, and how much modernization they enable.

To make the comparison concrete, think of the PLC as the ŌĆ£brainŌĆØ and the field wiring, I/O, and devices as the ŌĆ£nerves and musclesŌĆØ of your system. Some strategies replace only the brain, others rebuild the entire nervous system.

| Upgrade path | What changes | Typical downtime impact | Future flexibility | Typical use case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run as-is with mitigation | No upgrade; focused maintenance and spares | Minimal until a failure occurs | Very limited | Short-term stopgap when capital is unavailable |

| PLC migration (new CPU, existing I/O wiring) | Replace controller platform; reuse panels and field wiring | Low to moderate, often staged | Moderate | When downtime must be short and wiring is in good shape |

| Phased or hybrid modernization | Mix of old and new PLCs and networks during transition | Spread over multiple windows | High if roadmap is followed | Large facilities migrating line by line or subsystem by subsystem |

| Full control system replacement | New PLCs, I/O, wiring, panels, HMIs, and often networks | Highest, usually during major outage | Highest | When architecture is obsolete or major new capabilities are required |

Control Engineering authors describe ŌĆ£keep as-isŌĆØ as one of three strategic options: keeping the existing system, rewriting all code, or migrating existing programs to new hardware. The first option has the lowest immediate cost but carries increasing obsolescence and reliability risk. Some firms, such as R.L. Consulting, emphasize disciplined maintenance for legacy PLCsŌĆöstructured backups, regular panel inspections, and event-driven checks after power disturbancesŌĆöto stretch useful life and prepare for eventual retrofits.

For power-critical operations, this can be a short-term tactic while you build a capital plan. You might invest in preventive maintenance, stock key spares, and document as-built configurations. However, as vendors like Panelmatic and DoSupply point out, parts scarcity, unsupported software, and growing cyber exposure eventually make indefinite deferral unrealistic.

A PLC migration replaces the CPU and often some communication modules while reusing most of the I/O racks, panels, and field wiring. Panelmatic describes this as an upgrade path that keeps the existing wiring and field devices, converting or adapting the logic to the new hardware to preserve behavior and minimize physical changes. Balaji Switchgears calls a related pattern ŌĆ£direct replacement,ŌĆØ where old hardware is swapped for newer models while program architecture remains largely intact.

Industrial Automation Co. elaborates on how this works in detail. An effective migration often starts from the I/O and field wiring rather than the CPU choice. Engineers confirm input voltages, output types, and analog ranges, then select new modules engineered as behavioral clones. They recreate the legacy memory structure in the new PLC, using structured tags and aliases to mirror old registers, which reduces the need to rewrite well-behaved ladder logic.

Control Engineering highlights vendorsŌĆÖ hardware migration aids, such as wiring harnesses, terminal adapters, and retrofit kits. These let new PLC I/O connect directly to existing field wiring, drastically reducing panel rewiring. Schneider Electric similarly emphasizes plugŌĆæandŌĆæplay wiring adapters as a key success factor, avoiding the need to disconnect and reconnect hundreds of I/O wires and shortening cutover times.

The main advantages of this approach are clear. Material costs are lower because you reuse enclosures and wiring. Downtime is shorter because electricians are not pulling new cable for every point. Operator workflows remain familiar because the control behavior is preserved. Control EngineeringŌĆÖs case study of a municipal wastewater plant upgrading from multiple PLC-5 controllers to redundant ControlLogix units reported hot cutovers of roughly one PLC per day, with about twenty minutes for hardware cutover followed by testing and verification. That type of profile is attractive for a substation or UPS-switchgear PLC running in a plant that cannot afford multi-day outages.

The trade-offs are mostly architectural. Panelmatic notes that long-term flexibility can be constrained by older wiring and panel layouts, and any contamination or congestion in the original codebase is carried forward. Migration tools from Rockwell, Schneider, and others can convert logic automatically but still require careful review for unsupported instructions, data type differences, and subtle analog scaling behavior. You get a safer and more supportable system, but you may not fully exploit new capabilities like advanced diagnostics, modular programming structures, or integrated safety from day one.

For larger plants and networks of facilities, the dominant approach is phased or hybrid modernization. Balaji Switchgears describes phased migration as modernizing in stages by replacing components or modules over time, keeping production running while reducing downtime risk. Applied Manufacturing Technologies talks about structured, phased migrations from legacy Rockwell platforms across entire multi-line facilities, sequencing upgrades based on criticality and risk.

Phased strategies often combine elements of migration and new installations. GrayMatter describes a project for a U.S. chemical plant that upgraded to a modern PLC platform while intentionally preserving the existing legacy I/O system as an intermediate step. This reduced capital cost and implementation risk, with panel and cabinet upgrades carried out in partnership with plant staff to minimize disruption.

ContecŌĆÖs PLC upgrade checklist offers a practical view of phased modernization. For larger systems, their engineers often start by replacing only obsolete electronic hardware and keeping existing wiring in place via adapters. That lets the original software run with minimal changes. Once this is stable, teams can test and deploy updated logic in a second phase, with the option to revert quickly if needed. Even connector replacements can be deferred to future maintenance windows. For smaller or more flexible systems, they advise using the upgrade as an opportunity to clean up logic and tag structures rather than blindly copying existing code.

A hybrid approach is particularly attractive for power systems where you may have to coordinate multiple PLCs across switchgear, generator controls, and UPS or inverter skids. You might begin by migrating the PLC that supervises automatic transfer sequences using wiring adapters, while leaving downstream motor control centers on their existing controllers. In subsequent outages, you can fold those MCCs into the new architecture, standardize networks, and introduce unified diagnostics.

At the other extreme is a full replacement, sometimes called a ŌĆ£rip and replace,ŌĆØ in which PLCs, I/O, wiring, cabinets, HMIs, and often the network are redesigned and rebuilt. Panelmatic describes this as swapping the entire control system, including power supplies and control cabinets, to fully leverage stateŌĆæofŌĆætheŌĆæart hardware and architectures. Balaji Switchgears calls the analogous path a comprehensive system overhaul.

The benefits are substantial. You can adopt modern, modular architectures built around highŌĆæperformance controllers, standardized Ethernet-based networks, and integrated safety. You can re-segment networks for cyber resilience, design in redundant power supplies and processors, and introduce energy monitoring at feeder and load levels. Case studies from Schneider Electric and consulting engineers show how such projects can deliver future-ready systems, often with integrated PLC and DCS environments, and significantly improved cybersecurity.

The costs are equally real. Full replacement needs higher capital outlay and usually requires longer outages. One water treatment plant described in consulting engineering literature postponed a major SCADA and control upgrade for nearly a decade; when the work finally began, the team had to keep a live plant running, replace processors and I/O on an aging copper network with new fiber-based hardware, and carefully manage the cutover to keep downtime to minutes instead of hours. Engineering, testing, commissioning, and staff retraining all demand significant effort.

For power protection assets, full replacement makes sense when the existing architecture fundamentally cannot support needed reliability, integration, or compliance goals. An example would be a tripŌĆæcritical substation whose controls are a mix of bespoke logic, serial links, and hand-edited ladder with no documentation, where you need deterministic coordination between protective relays, PLCs, and SCADA, plus integrated cybersecurity controls.

Deciding between migration, phased modernization, and full replacement is ultimately a business decision grounded in technical realities. Across the research, several questions consistently help owners and engineers converge on the right path.

Applied Manufacturing Technologies recommends a criticality and risk assessment that ranks systems by how vital they are and the consequences of failure. For a line that packages non-perishable products, a weekend shutdown might be acceptable for a comprehensive replacement. For a data center UPS switchboard or a continuous chemical process, the tolerance may be measured in minutes or seconds.

Contec, PTE, and control system engineers stress the need to align upgrade strategies with realistic shutdown windows. If your substation PLC sits behind a UPS that can hold loads for fifteen minutes and your generators are sized for seamless takeover, a twenty-minute hot cutover similar to the Rockwell wastewater example may be practical. If your UPS autonomy is only a few minutes and you cannot transfer to utility or generator without complex reconfiguration, a phased or hybrid migration that moves logic gradually and maintains rollback options becomes more attractive.

A simple way to frame the decision is to calculate the economic impact of your maximum outage window. If your process loses $10,000 per hour when down and you can schedule an eight-hour outage once per quarter, you have a $80,000 ŌĆ£budgetŌĆØ of lost production per window. Deciding whether to spend that on one large, riskier full replacement or several smaller phased steps with lower per-step risk is a strategic choice.

ISD Automation, Lafayette Engineering, and DoSupply all emphasize lifecycle status and supportability as primary triggers. If your PLC platform is formally end-of-life, programming software no longer runs on supported operating systems, and spare parts can be obtained only through unreliable online channels, your risk is already elevated. Lafayette notes that installations older than roughly ten years are likely missing modern energy efficiency and performance improvements, especially when still tied to serial networking and outdated operating systems.

Performing a thorough installed-base inventory is the first step recommended by Contec and Applied Manufacturing Technologies. This involves cataloging controllers, I/O cards, networks, HMIs, wiring, and software versions, then flagging obsolete systems, critical nodes, and high-risk areas. For a power system, key nodes include generator sequencers, tie-breaker logic, and UPS or inverter controllers that cannot fail without significant impact.

The more obsolete and unsupported your core nodes are, the weaker the case for indefinitely deferring upgrades. In those situations, migration or phased modernization that addresses the highest-risk nodes first usually provides the best risk reduction per dollar.

Control EngineeringŌĆÖs experience in water and wastewater plants shows that poorly documented, individualistic programming styles can make migrations much harder. Where code is clean, structured, and well documented, migration tools and careful mapping can preserve behavior with manageable effort. Where logic is tangled, uncommented, and riddled with quick fixes, a full rewrite may be more appropriate.

Contec encourages using upgrades as an opportunity to improve tag structures and modularize code, particularly for smaller or more flexible systems. Industrial Automation Co. suggests rewriting logic only where one-to-one mapping is impossible, such as complex PID loops, motion instructions, or vendor-specific function blocks, while keeping discrete interlocks and sequences intact. However, they also note that a full redesign is often preferable when the original program is unreliable or when major new capabilities are being added.

For a power distribution PLC that has accumulated decades of patchwork changesŌĆötemporary load-shed logic, untracked relay mapping, half-implemented demand response routinesŌĆöa clean-slate rearchitecture during a full or major phased replacement may ultimately be safer and easier to sustain than carrying technical debt forward.

ISD Automation and Pacific Blue Engineering both argue that missing modern communication protocols, integrated safety, and robust data handling are strong indicators that upgrade is overdue. Many legacy PLCs cannot speak Ethernet/IP, MQTT, or OPC UA, limiting integration with SCADA, historian, cloud, or energy management systems.

PTE and CSE Magazine emphasize that modern control platforms are designed to meet current safety and cybersecurity standards, including those used in electric utilities and industrial functional safety. For facilities where regulatory compliance, energy reporting, or remote operations are priorities, platforms that support encrypted communication, granular access control, and integration with enterprise systems are essential.

In a power system context, that might mean moving from a legacy PLC that only exposes a handful of serial registers to a modern controller that can publish detailed breaker status, event logs, UPS alarms, and energy metrics into your plant historian and cybersecurity monitoring systems. If those capabilities are central to your business or regulatory expectations, a more ambitious migration or replacement that standardizes on a modern, well-supported family is justified.

Regardless of the path you choose, several practices show up repeatedly in successful migrations described by Schneider Electric, Contec, Control Engineering, PTE, and others.

Schneider Electric lists a thorough site assessment as the first critical success factor for seamless PLC migration. This assessment produces a report that identifies risks and recommended actions, helping maintenance and operations teams secure budget and prioritize projects. Operations personnel should be involved directly, because their day-to-day experience surfaces hidden issues and practical constraints.

Contec and Applied Manufacturing Technologies both view mapping the installed base as the starting point. For a power system, that means listing every PLC or controller that touches switchgear, protective relays, UPS, inverters, generator controls, and power metering. The inventory should include firmware versions, panel conditions, network diagrams, and any signs of overload or thermal stress.

GrayMatterŌĆÖs chemical plant project began with a comprehensive controls assessment, drawing on lessons from previous upgrades to shape a tailored roadmap. Consulting engineers on water plant projects recommend workshops with integrators, OEMs, and plant staff to align objectives, risks, and methods. In a substation context, that workshop should cover how the PLC interacts with relays, what fail-safe states are acceptable, and how long manual operation can be sustained during cutover.

Schneider Electric and Control Engineering highlight specialized wiring adapters and retrofit kits as powerful enablers. Rather than landing hundreds of existing field wires on new terminals, adapters let you unplug an old PLC chassis and plug in a new one with pre-mapped connections. This can reduce wiring errors and shrink hardware cutover windows dramatically.

Industrial Automation Co. extends this concept to network and memory structures. They recommend selecting CPUs that can behave as close as possible to the originals from the perspective of I/O, memory, and communications. Memory structures can be recreated using structured tags and aliases to mirror legacy addressing, minimizing logic changes. Where legacy serial networks must coexist with modern Ethernet, protocol converters and EthernetŌĆōserial bridges maintain communication with older drives and devices without forcing immediate replacement.

Vendor software tools are equally important. Schneider Electric references code conversion tools that translate legacy logic into formats compatible with modern platforms, preserving behavior and reducing the perceived risk of obsolescence. RockwellŌĆÖs migration tools can export older PLC-5 programs and bring them into Studio 5000. Control EngineeringŌĆÖs case study demonstrates how a custom SCADA tag conversion utility was used alongside vendor tools to adapt analog scaling, messaging, and PID instructions to a modern ControlLogix platform.

For a UPS and switchgear PLC, these tools might be used to bring existing breaker interlock logic and transfer sequences into a modern controller while keeping proven timing and interdependencies intact.

Contec underscores the importance of testing before cutover. Building a staging environment or using simulation allows teams to validate new logic, confirm I/O mappings, and check operator workflows outside of production. Similarly, PLC migration guides and forum-derived best practices advocate for ŌĆ£shadow modeŌĆØ operation, where a new PLC is wired in parallel, observing real inputs while its outputs are either disconnected or safely simulated, so behavior can be compared to the legacy system.

Control EngineeringŌĆÖs Rockwell case illustrates how careful planning can achieve near-zero-downtime upgrades: hardware cutovers were performed in about twenty minutes per PLC, with the rest of each day dedicated to software switchover, testing, and verification. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs thermal power facility case also emphasizes lowŌĆærisk migration and onŌĆætime delivery of a cyber-secure, future-ready system by using modernization kits and conversion tools.

PTE recommends running new systems in parallel with old ones where practical and stresses staff training during implementation. Forum-sourced best practices and integrator experiences echo the need for step-by-step procedures, fully backed-up programs, clearly labeled wiring, and rollback plans.

For power systems, realistic testing includes simulating loss of utility, generator start failures, UPS overload, and transfer between normal and bypass sources. It also should verify that, on PLC or communication failure, the system falls into a safe state that protects both equipment and personnel.

Schneider Electric presents a balanced migration team as the third critical success factor. Projects benefit from onŌĆæsite specialists with deep knowledge of both legacy and new platforms, backed by certified engineers who understand multiple PLC generations. These experts help ensure accurate code translation and avoid technical oversights that would otherwise surface during commissioning.

Pacific Blue Engineering and PTE both emphasize thorough training and documentation. Operators and maintenance staff need to understand new diagnostics, alarm structures, and manual override procedures. R.L. Consulting similarly notes that maintenance effectiveness depends on clear, up-to-date documentation and knowledge transfer so inŌĆæhouse teams can handle first-line troubleshooting.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs standpoint, this is non-negotiable. A beautifully executed technical migration can still fail operationally if the night shift is unsure how to respond to a new alarm or if a field electrician cannot interpret updated schematics during a storm-induced outage.

Beyond immediate reliability, migrating to modern PLCs changes your cyber and compliance posture and expands what you can do with power system data.

Consulting engineers writing on legacy control system upgrades point out that modern platforms incorporate stronger security controls, such as encryption, granular access control, and real-time monitoring. In electric utilities, control system upgrades help facilities comply with standards like NERC CIP and widely used information security frameworks. PTE notes that modern automation systems are designed to meet current safety and functional standards such as ISO 13849 and IEC 61508, reducing regulatory risk and potential fines.

R.L. Consulting extends the picture by referencing industrial cybersecurity standards like ISA/IEC 62443, which guide secure access, network design, and patch management for networked PLCs. Legacy controllers on flat serial networks with shared passwords simply cannot meet these expectations.

On the data side, modern PLCs and automation systems support higher processing capacity and more advanced data structures. Articles from ISD Automation and DoSupply highlight that newer platforms can handle more sensors, faster sampling, and richer data logging. Industrial research summarized by ISD suggests that real-time data access can boost production efficiency by up to twenty percent, while examples such as a Siemens-based upgrade in a pharmaceutical facility delivered a forty percent reduction in energy use for environmental control systems.

For power and energy management, modern PLCs become key nodes in a broader information architecture. They can publish breaker operations, UPS load trends, inverter efficiency, and energy metering data to historians and analytics engines. PTE emphasizes that modern systems can track energy usage in real time and support data-driven decisions to reduce consumption and environmental impact. DoSupply notes that real-time energy monitoring and control can directly reduce energy costs while lowering scrap through better process control.

When your PLC modernization is aligned with these data and cyber objectives, you are not just replacing aging hardware. You are creating a platform for continuous energy optimization, more rigorous incident forensics, and integrated security monitoring across your power infrastructure.

Consider a facility where a legacy PLC-5 coordinates automatic transfers between utility, generator, and a large double-conversion UPS feeding critical loads. Documentation is partial, the programming laptop runs an old operating system, and spare cards must be scavenged from secondary markets. The facility can schedule two planned outages of eight hours per year, and unplanned downtime carries a six-figure cost per hour.

An installed-base audit following the patterns recommended by Contec, PTE, and Applied Manufacturing Technologies reveals that while the PLC chassis and communication hardware are obsolete, the field wiring, breakers, and UPS remain in good condition and have many years of life left. The code is functional but cluttered, with limited comments.

From the alternatives described above, a PLC migration with phased logic cleanup is often the most balanced path. Migration-friendly hardware from a modern PLC family can be selected to align I/O voltages and signal types. Wiring adapters minimize panel work, reducing the risk of mis-landing critical breaker interlocks. Vendor and third-party tools convert the legacy ladder logic into the new environment, preserving tested sequences.

During the first planned outage, the old CPU is replaced, wiring adapters are installed, and converted code is loaded. Hardware cutover, I/O checkout, and initial functional testing are completed. For the next several months, the new PLC runs with logic that closely mirrors the old program, while operators and maintenance staff become familiar with new diagnostics and HMIs.

In a second phase, scheduled during the next outage window, the engineering team refactors the logic into more modular structures, introduces improved alarm and event logging, and enables Ethernet-based communication with the plant historian and cybersecurity monitoring systems. Over time, additional energy meters and status signals from the UPS and switchgear are integrated, enabling detailed analysis of load profiles and power-quality events.

This scenario aligns closely with best practices described across the research: phased migration, reuse of sound field infrastructure, leveraged use of migration tools and wiring kits, and early focus on critical risk nodes. It avoids the worst-case risk of an unsupported CPU failure while building a platform for future improvements.

In specific cases, yes, but only with eyes open and a defined horizon. Consulting and integrator guidance agrees that running an obsolete controller indefinitely without a roadmap is dangerous. Where capital or outage windows are constrained, you can combine disciplined preventive maintenance, spares strategies, and enhanced monitoring to mitigate risk in the short term. However, lifecycle assessments like those described by ISD Automation and DoSupply show that maintenance costs and failure risk rise as equipment ages. For PLCs supervising critical UPS and switchgear logic, that tipping point arrives sooner than for non-critical processes. The better strategy is to treat short-term mitigation as a bridge to a planned migration or replacement.

Most sources emphasize consistency and lifecycle support more than absolute single-vendor purity. Panelmatic and Pacific Blue Engineering both recommend selecting platforms with strong long-term support, modern protocols, and scalability. PLC migration specialists point out that standardizing on a family such as a modern Logix or SIMATIC series simplifies support, training, and spares. However, Industrial Automation Co. and others routinely bridge communications between different generations and brands using protocol converters and flexible HMIs. In a large facility, it is practical to converge on one or two primary platforms while using gateways and careful design to integrate necessary exceptions, especially where OEM equipment comes with embedded controllers.

Every plant is different, but from a reliability and risk standpoint, PLCs that directly impact personnel safety, regulatory compliance, and the ability to power down or recover safely should be near the top of the list. ISD Automation and CSE Magazine both frame upgrade decisions in terms of risk and consequence of failure. For many facilities, loss of a switchgear or UPS PLC brings wider consequences than loss of a single packaging cell, because it affects emergency egress lighting, fire systems, and life-safety loads. A risk-based prioritization, as recommended by Applied Manufacturing Technologies and others, will typically place power system controls in the highest criticality tier, alongside high-hazard process units.

Upgrading legacy PLCs is not just a controls refresh; it is a foundational move to keep your UPS, inverter, and power protection systems reliable in an increasingly demanding, data-driven, and security-conscious grid. When you treat migration as a structured, risk-managed program rather than a last-minute reaction to failure, you protect both your power system and your business continuity for the long haul.

Leave Your Comment