-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

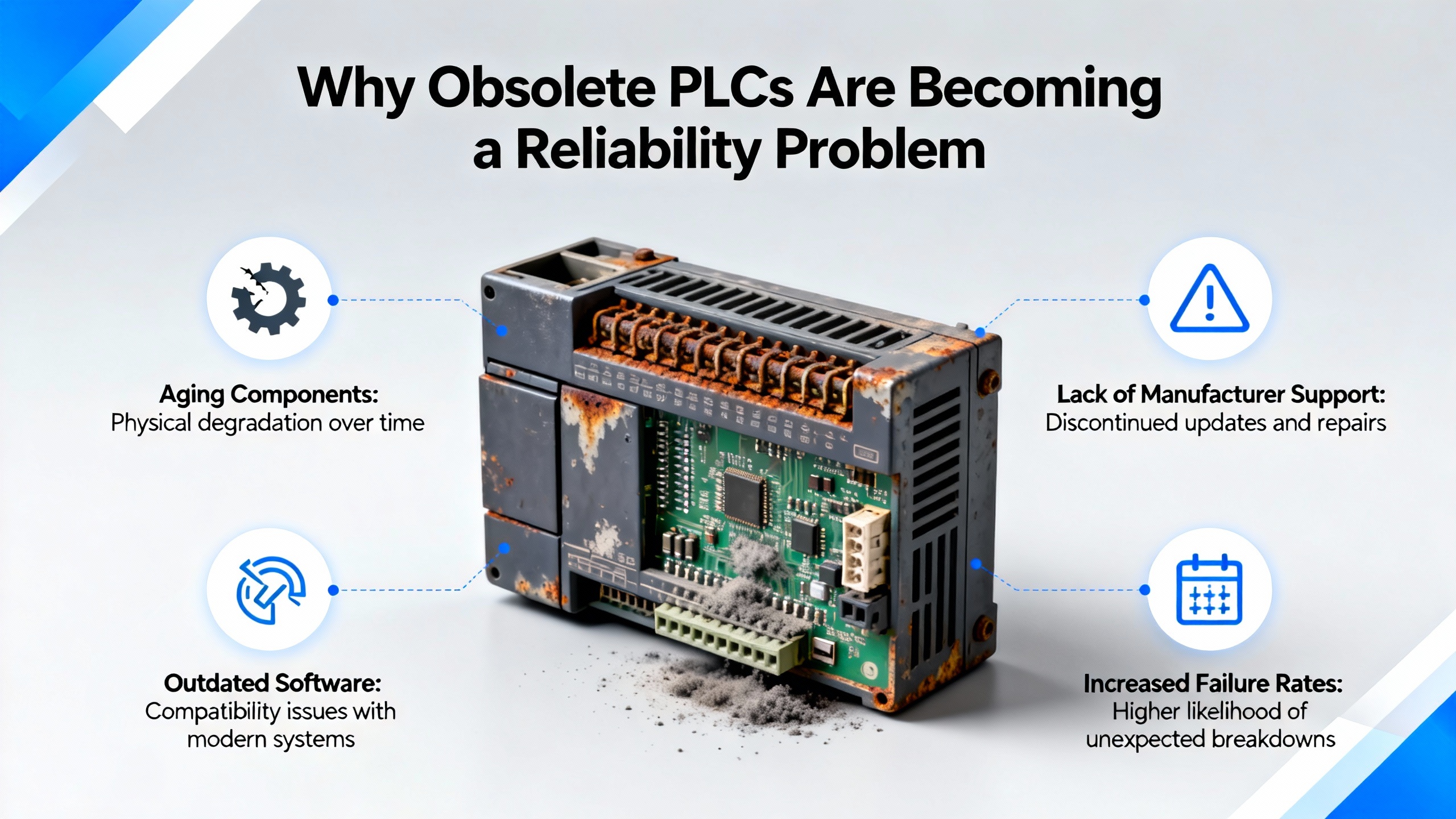

Industrial and commercial power systems rely on control reliability just as much as they rely on kilowatts. In a data center UPS room, a hospital microgrid, or a utility substation, the programmable logic controllers sitting behind switchgear, inverters, and static transfer switches often decide whether the lights stay on. Many of those PLCs were installed twenty or thirty years ago and are now discontinued. Spare parts are hard to find, engineers who know the old software are retiring, and a single failed CPU can take down a critical bus.

From the perspective of power reliability, obsolete PLCs are a strategic risk, not just a maintenance nuisance. Research from suppliers and integrators such as DO Supply, Panelmatic, Wood, and Balaji Switchgears consistently points to the same pattern: aging controllers bring higher downtime risk, rising maintenance cost, poor cybersecurity, and difficulty integrating with modern monitoring and analytics. At the same time, the wrong replacement strategy can create its own hazards through rushed rewiring, untested logic, or extended outages.

This article looks at practical replacement options when your PLC platform is discontinued, focusing on power-related applications. The goal is to help you answer four decisions that reliability owners actually wrestle with: whether to extend or replace, whether to stay with the same platform, how much downtime you can afford, and whether you still need a PLC at all for a given function. Along the way, we will draw on concrete practices and examples from the sources in your research brief and from real-world power system projects.

A PLC is essentially a rugged industrial computer that reads inputs from sensors and switches, executes control logic, and drives outputs such as breakers, contactors, fans, and valves. Panelmatic and DO Supply both describe how these devices were built to survive harsh conditions and can run for decades. That longevity is a blessing for capital budgets but a curse for lifecycle support.

DO Supply defines a legacy PLC as one whose hardware or software is no longer updated or fully supported by the original manufacturer, and that starts to slow down operations, block new features, or hinder expansion. They list common characteristics: no regular security or technical updates, incompatibility with current programming tools and networks, dependence on obsolete operating systems, scarce and expensive spare parts, and heavily patched software that has been modified by many hands. Control Engineering adds that hardware obsolescence and spare-part risk are primary triggers for upgrades and cautions against relying on ad hoc internet purchases for critical spares.

Wood highlights the broader control-system context across SCADA, PLC, and DCS platforms. Many installations date back decades, and as vendors end support, operators face more unplanned downtime, rising maintenance costs, integration difficulty with modern digital tools, compliance gaps, and increased cybersecurity exposure. In a power system, those risks translate into blackouts, transfer failures, nuisance trips, or stuck breakers rather than just lost widgets.

From a reliability standpoint, obsolescence also collides with downtime cost. Digi-Key notes that downtime often runs in the hundreds to thousands of dollars per minute once you factor idle staff, scrap, overtime, and goodwill. In a UPS-backed data center or an industrial plant with critical furnaces, the cost of a four hour outage while someone hunts for a used PLC module online can easily dwarf the price of a well-planned modernization.

Consider a simple example. Imagine a switchgear PLC that has been out of production for ten years. You have no local spares left, the OEM has stopped stocking the CPU, and the only replacement you can find is from a secondary marketplace on the other side of the country. Even if the part is genuine, by the time it ships, arrives, and is tested, your emergency transfer scheme could be down for an entire business day. If your estimated downtime cost is even a modest one thousand dollars per minute, a single incident can wipe out the savings from postponing the upgrade for years.

The takeaway is that obsolete PLCs do not just make engineers uncomfortable; they directly expose critical power systems to extended outages. That is why many sources in your research treat PLC modernization as a strategic necessity rather than a nice-to-have.

Every reliability engineer has been asked to ŌĆ£keep it running just a bit longer.ŌĆØ In some situations, that is a rational strategy, especially when your power system is otherwise stable and capital budgets are tight. Several sources outline ways to extend the life of legacy controllers, along with the traps you need to avoid.

Applied Manufacturing describes how some plants stockpile spare parts ahead of obsolescence to reduce the risk of shutdowns. Industrial Electrical Warehouse notes that many facilities continue to operate decades-old equipment successfully by sourcing obsolete contactors, relays, PLC modules, and motor starters from specialized suppliers. These vendors maintain inventories of discontinued components, offer cross-reference guidance to compatible part numbers, and help verify authenticity to reduce counterfeit risk.

There are important caveats. Applied Manufacturing points out that stockpiling is complex and expensive, especially when you have many machines. Overstocking can backfire because components held for years fall out of warranty, lose resale value, and still march toward their own obsolescence. They also warn that OEMs often raise prices as parts near end of life and then publish end-of-support notices, leaving customers with a shrinking window to act. Industrial Electrical Warehouse emphasizes the need to verify condition and provenance when buying from auctions, surplus inventories, or online marketplaces where refurbished parts might be sold as new.

On the software side, Applied Manufacturing explains how software obsolescence can force users to maintain older laptops, operating systems, and interface cards just to program legacy equipment. That arrangement is feasible for a while but demands specialized skills and adds time to every troubleshooting event.

From a power-system reliability perspective, life extension is most defensible when three conditions hold. First, the PLCŌĆÖs role is not tightly coupled to instant protection functions; for example, it supervises a noncritical load bank rather than an automatic transfer system. Second, you can secure high-quality, tested spares from reputable obsolete-parts suppliers rather than relying solely on random online auctions. Third, you deliberately treat life extension as part of an obsolescence management plan, not as a passive run-to-failure stance.

Industrial Electrical Warehouse recommends exactly that: keep a registry of aging components, track their production status, and proactively source critical spares before they vanish. Wood and DO Supply both stress that obsolescence should be managed as a strategic risk. In practice, that means setting clear triggers for when you shift from life extension to active replacement. For example, you might decide that once OEM support ends and aftermarket CPUs cross a certain price or lead-time threshold, the PLC must move onto your formal modernization roadmap.

As a quick calculation, think about a UPS plant where three switchgear lineups each depend on a discontinued PLC. If you want two CPU spares per lineup, that is six units. Multiply by the current aftermarket price per CPU, and then add the overhead of periodic test cycling to ensure they still power up. By the time you account for that sunk cost and the residual outage risk if a spare fails on installation, the economics often start to look similar to a well-planned migration.

Once you accept that indefinite life extension is not sustainable, the next choice is whether to stay with your existing vendor family or move to a different platform. This is not just about specifications; it is about the skills, ecosystem, and lifecycle that will support your power system for the next decade.

Digi-Key emphasizes that PLCs have decade-long lifecycles and that many different roles touch them over time, from integrators and machine designers to programmers, technicians, and future engineers. Because staff change over the years, they argue that soft requirements such as consistency of PLC families across a facility, software tool commonality, workforce skills, and long-term ecosystem support often outweigh initial hardware cost. They note that many buyers choose PLCs based on popularity and ecosystem strength specifically as a hedge against obsolescence, expecting that parts and third-party repair services will remain available well into the future.

A concrete example is Rockwell AutomationŌĆÖs SLC 500 family. Digi-Key points out that it was introduced more than thirty years ago and discontinued about ten years ago, yet second-hand or repaired modules are expected to remain available for decades. That longevity does not eliminate obsolescence risk, but it illustrates how a widely adopted platform can give you more options when parts go end-of-life.

Atlas OT, which focuses on SLC 500 modernization, describes one vendor-specific path: migrating to RockwellŌĆÖs CompactLogix 5380 platform. Rockwell supplies tools such as Integrated Architecture Builder for hardware planning and Studio 5000 conversion utilities that translate ladder logic into Logix code. Control Engineering and InnoTech both describe manufacturer-provided conversion kits and logic-conversion tools that allow you to reuse existing swing arms and field wiring, reducing downtime and risk when you stay within the same vendor family.

At the same time, Atlas OT notes that alternative PLC platforms such as IDEC, Opto22, or Phoenix Contact PLCnext can be cost-effective choices depending on your requirements. Contec and Panelmatic both emphasize platform selection criteria that go beyond brand loyalty: compatibility with existing assets, use of open standards, alignment with SCADA and MES architectures, vendor support horizon, and your teamŌĆÖs familiarity with the tools. DO Supply adds that modernized PLCs based on more open hardware technologies can give integrators more flexibility and avoid being locked into proprietary ecosystems.

For power systems, the standardization argument is powerful. When the same PLC family runs your generator switchgear, UPS input and output breakers, dynamic transfer switches, and key inverter controls, your technicians only need to master one software environment and one style of tag naming. Digi-Key notes that tag-based systems with readable names aligned to P&IDs and HMI labels make life much easier for new personnel compared with legacy numeric data tables. That ease translates into faster troubleshooting at two in the morning when a transformer overload alarm is blinking.

Imagine two scenarios over the next ten years. In the first, you standardize on a single mainstream PLC platform for all your power controls and use the same engineering tools and training material everywhere. In the second, each retrofit project picks a different platform based on whoever offered the lowest quote that year. Even without detailed financial modeling, it is clear which scenario gives you a simpler spare-parts strategy, a cleaner training plan, and lower long-term risk when you eventually modernize again.

In practice, most reliability-focused organizations stay with the same PLC vendor family when feasible, especially for large installed bases, and consider switching only when there is a compelling reason such as unsatisfactory support, poor fit with new cybersecurity requirements, or an opportunity to simplify around a different standard.

Your allowable downtime window is often the single strongest constraint on replacement strategy. An industrial chiller supplying a data centerŌĆÖs UPS room may have a short seasonal maintenance window and high redundancy, while a single main-tie-main switchboard in a hospital may never be allowed to go cold. Different strategies fit different realities.

Contec notes that effective PLC upgrade projects share three traits: early planning, thorough testing, and adaptable designs. They recommend mapping the installed base to identify obsolete systems and critical nodes before any change, then defining project scope and platform choices. For large, complex systems with tight uptime requirements, they suggest a hardware-first strategy that replaces obsolete electronics while keeping existing wiring and connectors through adapters, allowing the original software to continue running. Logic updates can then be introduced in a second phase once the new platform is stable, with a clear option to revert if needed.

InnoTech gives very concrete guidance on I/O migration for PLC-5 replacements with two methods: a swing-arm conversion approach and full rewiring. Using conversion hardware, a technician can connect a single PLCŌĆÖs wiring in less than ten minutes by reusing the existing swing arms and chassis. That speed is a game changer during short outage windows and reduces the chance of wiring errors or wire damage. The tradeoffs are added hardware cost and reduced accessibility because the new chassis mounts over the old one, making some maintenance tasks harder.

Control Engineering describes similar manufacturer conversion kits as a low-risk, low-downtime approach that reuses existing field wiring and avoids extensive I/O checking. They contrast that with full rewiring, which is more time-consuming but offers greater long-term flexibility and a clean break from legacy layouts. InnoTech echoes this, noting that rewiring improves connection reliability, supports better per-point troubleshooting, and even allows live swing-over or hot swap with good planning, but requires more expertise and time, with the added risk of encountering brittle legacy wires that must be replaced.

Balaji Switchgears frames these choices as part of a continuum from direct replacement through phased migration to comprehensive overhaul. Direct replacement swaps old hardware for newer models while keeping existing program architecture, suitable for smaller systems and tight outages but not fully exploiting modern features. Phased migration and hybrid solutions combine old and new components to maintain production while gradually modernizing, while a full system overhaul delivers maximum scalability and advanced integration at the cost of higher upfront investment and more involved planning.

Industrial Automation Co, writing on modernization of obsolete drives and legacy controls, recommends a similar phased model: stabilize operations with drop-in replacements that match voltage ranges, communication standards, and control logic closely enough to support a near swap-and-start changeout, then schedule controller, HMI, and network upgrades during planned outages. Their example of a control cabinet refresh reused wiring paths and terminal blocks while swapping obsolete components for direct-fit new drives and PLCs, resulting in a cleaner design and higher reliability without extensive downtime for reprogramming.

For power systems, you might use these patterns in different ways. A noncritical building load center can often tolerate a full-day outage for a clean rewire and reprogram, which pays off in long-term maintainability. A main emergency power switchboard that feeds life-safety loads may require a staged approach: install new controllers and wiring in parallel, simulate heavily, and then perform a hot cutover during a tightly controlled window with rollback options.

A simple planning exercise can help clarify your real downtime tolerance. List your major PLC-controlled power assets and, for each one, write down the longest outage you can realistically accept during a planned change, measured in hours. Then consider how long it took your team to rewire and recommission a similar system in the past. If the required work cannot fit the window, you should lean toward direct-fit or phased strategies, even if they cost more upfront, and reserve full rewiring and reprogramming for assets with more flexible maintenance slots.

Not every obsolete PLC should be replaced by another PLC. A few of your research sources highlight alternatives that can make more sense, especially for distributed power and infrastructure systems.

DPS Telecom compares PLCs with Remote Telemetry Units in SCADA environments. They note that while PLCs are powerful, they require significant programming expertise and are primarily optimized for manufacturing environments. RTUs, by contrast, are purpose-built for remote site monitoring and control, with rugged construction, greater monitoring and control capacity across diverse devices, built-in detailed alarm notifications, and integrated communications. Crucially, RTUs often arrive pre-configured or pre-programmed by the manufacturer, which reduces dependence on in-house programming skills and simplifies training of new staff.

For geographically dispersed networks such as telecom shelters, remote substations, or renewable plants with inverters scattered over miles, DPS argues that RTUs are often better aligned with needs than traditional PLCs. They emphasize features that matter for power-system reliability: control relays for remotely operating generators and HVAC, rich alarm detail that cuts truck rolls, web interfaces reachable from any browser, redundant communication paths, and redundant power feeds. In effect, an RTU can serve as both controller and eyes-and-ears for remote assets.

Industrial Automation Co, from the drive side, shows another pattern where modern smart devices reduce the required PLC footprint. Many newer variable-speed drives and servo drives include advanced diagnostic and control capabilities. Their modernization roadmap explains how drop-in replacement drives can integrate tightly with existing PLC and HMI networks while taking on more local control functions and providing richer diagnostics and historian data. In power systems, similar logic applies to intelligent protective relays, smart switchgear, and modern UPS systems that offer extensive internal logic, alarms, and remote interfaces. While these sources do not claim that such devices eliminate PLCs entirely, they illustrate a trend toward distributing intelligence.

In practical terms, when planning a replacement for a discontinued PLC, it is worth asking whether an RTU, a smart relay, or an intelligent device already present in your power system could assume some or all of the logic. In a remote generator site, an RTU with built-in control relays might be a more robust and supportable choice than a small PLC, especially if you struggle to maintain PLC programming skills on staff. In a switchboard with intelligent relays already handling protection and metering, a smaller supervisory PLC or even direct SCADA integration might suffice after modernization.

The key is to design higher levels of automation and visibility so that a small core of experts can create systems that new staff can operate reliably for many years, as DPS recommends. That often means leveraging vendor-supplied configurations and focusing your in-house engineering effort on site-wide integration, alarming philosophy, and cybersecurity rather than low-level device logic everywhere.

Once you have answered the big picture questions about life extension, platform choice, downtime, and controller type, you can pick a concrete replacement path. The research notes outline four main patterns that appear repeatedly in real projects.

Industrial Electrical Warehouse, Applied Manufacturing, and Digi-Key all describe strategies to keep legacy systems alive through calculated spare-part stockpiles and targeted sourcing. This path is attractive when budgets are constrained or when the risk of change feels higher than the risk of failure, such as in a stable switchboard that has run cleanly for years.

The pros are obvious. You avoid a major modernization project, keep familiar behavior, and can plan upgrades on your own schedule. Experienced obsolete-part suppliers bring value by cross-referencing old part numbers, recommending form-fit-function replacements, and helping identify retrofit options when an exact part no longer exists.

The cons are equally real. OEMs progressively withdraw support and inventory, prices climb, and counterfeit or marginal-quality parts become more common. You may end up maintaining a zoo of old programming tools and operating systems to service different vendor families. Applied Manufacturing warns that the extra time, specialized hardware, and complexity involved in supporting old systems can eventually make a full upgrade more attractive and economically justified despite up-front cost and downtime.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs standpoint, this option is best treated as a bridge, not a destination. It buys time to plan and budget a structured modernization while reducing immediate outage risk, but it should sit inside a documented obsolescence management plan with clear exit criteria.

Direct-fit replacements and manufacturer conversion kits are a powerful tool when you need to replace discontinued PLCs with minimal disruption. Control Engineering explains that conversion kits reuse existing swing arms and field wiring, drastically cutting on-site installation time. InnoTechŌĆÖs swing-arm method is a specific example: using IO adapter plates, conversion modules, and pre-wired cables, a technician can connect a single PLCŌĆÖs wiring in under ten minutes, reducing rewiring errors and wire damage.

Industrial Automation Co shows how this pattern extends beyond CPUs to drives and other control components. They describe modern hardware designed with matching voltage ranges, communication standards, and control logic so that users can keep existing wiring, I/O, and ladder logic in a near swap-and-start changeout. Their cabinet refresh example achieved a cleaner design and higher reliability while reusing existing wiring paths and terminal blocks, avoiding extended downtime for reprogramming.

The main advantages are short outages, lower wiring risk, and a relatively predictable scope. The limitations are that you largely preserve the existing architecture and sometimes the existing logic. Balaji Switchgears notes that direct replacement does not fully exploit modern PLC capabilities such as advanced diagnostics, modular programming, or cloud integration. DO Supply also warns that while conversion tools can translate legacy logic into modern environments, they rarely take advantage of features like redundancy, advanced security, or more maintainable data structures.

For power systems, direct-fit upgrades are particularly attractive for critical switchboards, UPS transfer logic, and generator controls where outages must be measured in minutes instead of hours.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are full migrations where you redesign the control architecture, rewire IO, and write new code. Balaji Switchgears, Panelmatic, Contec, Atlas OT, Pacific Blue, and DO Supply all describe this as the path that delivers maximum long-term benefit: higher reliability, lower maintenance cost, improved productivity, better flexibility, and stronger cybersecurity.

InnoTech and Control Engineering highlight the software advantages. Modern PLCs support tag-based addressing instead of legacy data tables, enabling tag names that match P&ID tags and HMI labels for easier troubleshooting. They also support user-defined datatypes and modular code structures, which keep programs organized and maintainable across multiple controllers. DO Supply notes the performance and availability gains from modern PLC features such as processor, power, and network redundancy, as well as predictive diagnostics on components like power supplies.

The cost is upfront effort. Panelmatic lays out a process that begins with site evaluation and IO audit, moves through system design and platform selection, panel fabrication or rework, software and HMI development, factory acceptance testing, installation and commissioning, and operator training. Contec recommends building a staging or simulation environment to validate new logic and IO mappings before cutover. Pacific Blue emphasizes the need for a cost-benefit analysis that includes hardware, software, installation, testing, training, and maintenance, balanced against monetized benefits like uptime, throughput, and reduced scrap.

For a power system, a full migration is often justified when you face multiple converging drivers: obsolete hardware, unsupported software, cybersecurity requirements, integration needs with modern SCADA or energy management systems, and a desire to standardize across sites. It is also an opportunity to standardize alarming, sequences of operation, and naming conventions so that different units of your fleet behave consistently.

Between life extension and full migration lies a family of hybrid strategies. Balaji Switchgears describes hybrid solutions that combine old and new PLC components, enabling gradual modernization that balances cost control with operational continuity. Contec suggests a two-phase approach where you first migrate hardware while keeping logic largely intact, then gradually refactor the control software once the new platform proves stable. Even connector replacements can be postponed to later maintenance windows to spread risk and effort.

Industrial Automation Co recommends stabilizing production with drop-in replacements first, then scheduling more invasive controller, HMI, and network upgrades during planned outages. Panelmatic underlines the importance of defining project scope clearly, whether you are targeting a one-off replacement or a broader standardization program across a fleet of assets.

A practical hybrid pattern for power systems might look like this. In the first phase, you replace discontinued PLC hardware on a one-for-one basis using conversion kits, keeping all IO and existing logic and focusing mainly on eliminating hardware obsolescence. In the second phase, you modernize HMI graphics, refactor logic into standard modules, and introduce advanced diagnostics and remote monitoring. In the third phase, you tackle network upgrades, cybersecurity improvements, and tighter integration with SCADA or historian platforms.

This approach keeps each step manageable and offers several safe points where you can pause, stabilize, and reassess before moving further.

The options above can be summarized in a simple comparison.

| Strategy | Typical Use Case | Main Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life extension via obsolete parts | Stable systems needing a short-term bridge | Low immediate disruption, low engineering effort | Growing spare scarcity, counterfeit risk, rising maintenance burden |

| Direct-fit / conversion-kit upgrade | Critical assets with very tight outage windows | Minimal downtime, reuse wiring, lower wiring risk | Limited architecture change, may not exploit modern features fully |

| Full re-engineered migration | High-value systems needing long-term modernization | Maximum functionality, cybersecurity, and flexibility | Highest upfront cost, longer outages, significant engineering and testing |

| Hybrid / phased migration | Large fleets or constrained budgets | Balances risk and cost over time, allows learning curve | Requires careful coordination, temporary complexity with mixed old and new |

The right choice depends on your risk tolerance, budget, and strategic horizon. For many critical power systems, the answer is a hybrid: eliminate the worst hardware obsolescence quickly, then progressively move toward a fully modernized architecture.

Regardless of which replacement path you choose, the quality of your planning and testing often determines whether the project actually improves reliability or simply trades one risk for another.

Contec advises starting with a thorough installed-base inventory. That means documenting what runs where, including hardware models, firmware versions, IO counts, network connections, and integration points with SCADA, HMIs, and other systems. InnoTechŌĆÖs Front-End Engineering Design concept serves a similar role for PLC-5 migrations, identifying gaps in control systems, prioritizing critical components, confirming power and environmental capacity, examining HMI and alarm impacts, and ensuring networks are up to date and compatible.

Risk assessment is the next piece. Although the ICAD Automation article could not be retrieved, your notes describe common industry practice: documenting the current state, identifying hazards and failure modes, evaluating likelihood and impact, and assigning risk levels to guide mitigation. In a power system, typical hazards include unintended breaker operations, loss of synchronizing control, incorrect transfer sequencing, or blinded alarm paths in SCADA. A structured risk assessment before a PLC upgrade should explicitly consider these scenarios and define protective measures and rollback plans.

Testing is where many projects underestimate effort. Contec recommends building a staging or simulation environment, ideally with real hardware, to validate new logic, IO mappings, and operator workflows before touching production. InnoTech stresses that alarms often do not convert well with automated tools and should be reconfigured and tested carefully, preferably with the help of experienced integrators. Industrial Automation Co advises backing up all drive and PLC parameters, labeling every wire and IO mapping, and bench-testing new hardware with the same control signals before connecting to live production, noting that these practices prevent most common upgrade pitfalls.

Cybersecurity is a growing driver for replacement. DO Supply and Wood both highlight how legacy PLCs often lack modern security patches and protocols, making them attractive targets for cyberattacks. InnoTech observes that migrating from serial connections to Ethernet/IP may require new firewalls and network switches. Pacific Blue emphasizes the need to examine cybersecurity gaps and include them in the cost-benefit and opportunity-cost analysis for upgrades. Practical steps include isolating control networks, applying vendor security hardening guides, segmenting traffic with managed switches, and ensuring that remote access is secure and auditable.

Documentation and training close the loop. Panelmatic, Balaji Switchgears, and Pacific Blue all stress the importance of operator and maintenance training during and after upgrades. Industrial Automation Co recommends recording firmware versions, parameter backups, as-built wiring diagrams, and network topology to speed future troubleshooting. In a power system environment where staff turnover is inevitable, clean documentation and common programming standards across PLCs can be the difference between a quick, safe recovery and a prolonged outage during a shift change.

A simple example illustrates the value of testing. Suppose you modernize a UPS switchgear PLC and adopt tag-based addressing and a new HMI. In a staging environment, you simulate an overload scenario and notice that the ŌĆ£TripŌĆØ alarm is mapped to the wrong tag, so the HMI displays a generic warning instead of the specific breaker and feeder involved. You fix the mapping in minutes. If that error had been discovered during a real overload event in the live system, operators might waste critical time identifying the affected feeder while the load rides close to its limits.

Yes, under the right conditions. Sources such as Industrial Electrical Warehouse and Applied Manufacturing show that many plants successfully maintain legacy PLCs for years by sourcing obsolete parts, planning stockpiles, and using specialized repair services. Wood and DO Supply, however, emphasize that obsolescence raises risks of downtime, higher maintenance cost, and cybersecurity exposure. From a power reliability standpoint, continuing to run a discontinued PLC makes sense when the function is noncritical, high-quality spares and repair paths are secured, and there is a documented plan and budget to modernize before support collapses entirely.

Financially, the business case rests on avoided downtime, lower maintenance cost, improved security, and the opportunity to support future initiatives. Digi-Key highlights that downtime can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars per minute. DO Supply and Panelmatic describe how aging PLCs drive maintenance expenses up through frequent failures, slow repairs, and scarce skills. Pacific Blue recommends a cost-benefit analysis that lists all upgrade costs and compares them against monetized benefits such as higher throughput, better reporting, remote monitoring, reduced scrap, and reduced outage risk. In a critical power context, you can often frame modernization as insurance against a low-frequency but high-impact failure that could exceed the entire cost of the upgrade in a single event.

You can, but you should not ignore modernization entirely. Applied Manufacturing suggests that a calculated spare-parts stockpile and a specialized support team can be part of a good obsolescence strategy, especially for smaller installed bases. Industrial Electrical Warehouse recommends pairing spare sourcing with proactive obsolescence management, including a registry of aging components and their production status. Wood and Balaji Switchgears both advise treating modernization as a strategic necessity rather than an optional project. For a small number of noncritical power assets, it can be reasonable to stabilize with spares while you develop a multi-year modernization roadmap that prioritizes the highest-risk systems first.

| Publisher or Provider | Topic or Angle on PLC Obsolescence |

|---|---|

| Balaji Switchgears | Structured strategies for PLC modernization and hybrid migrations |

| Applied Manufacturing | Obsolete components, spare-part stockpiling, and lifecycle planning |

| Contec Industrial Automation | PLC upgrade checklists, phased hardware-first migrations, testing |

| Digi-Key | Soft requirements, ecosystem choices, and downtime cost considerations |

| DO Supply | Pros and cons of upgrading legacy PLC systems |

| Industrial Automation Co | Direct-fit replacements and drive modernization strategies |

| Industrial Electrical Warehouse | Sourcing obsolete parts and keeping legacy systems alive |

| InnoTech Engineering | Detailed options for replacing PLC-5 systems |

| Atlas OT | Modernizing Rockwell SLC 500 PLCs and platform choices |

| Control Engineering | Strategies and tradeoffs for upgrading PLC hardware |

| DPS Telecom | When RTUs are better suited than PLCs for remote control |

| Panelmatic | Why, when, and how to modernize PLC-based control systems |

| Wood | Control system obsolescence management and cybersecurity risks |

As a power system specialist, my recommendation is to treat obsolete PLCs in your UPS, inverter, and switchgear fleets the same way you treat aging breakers or batteries: as assets with a finite, predictable lifecycle. Use life-extension tactically, choose platforms and partners that can support you for the long run, and design migration paths that protect uptime while moving you toward a more visible, cyber-secure, and maintainable control architecture.

Leave Your Comment