-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Legacy programmable logic controllers are quietly turning into some of the highest-risk components in industrial and commercial facilities. They still run lines, switch power, supervise UPS-backed loads, and sequence inverters, but they do it with aging hardware, disappearing spare parts, and limited visibility. In my work helping plants modernize automation and power infrastructure, I see the same pattern again and again: the control system fails at the exact moment the process or the electrical system is stressed the most. By then, it is too late to plan.

Replacing legacy PLC systems is not just a controls project. It is a reliability project that touches power quality, UPS and inverter coordination, safety, cybersecurity, and long-term lifecycle cost. This article walks through practical modernization and upgrade options, grounded in field-proven guidance from manufacturers and integrators, and framed from the perspective of a power system specialist and reliability advisor.

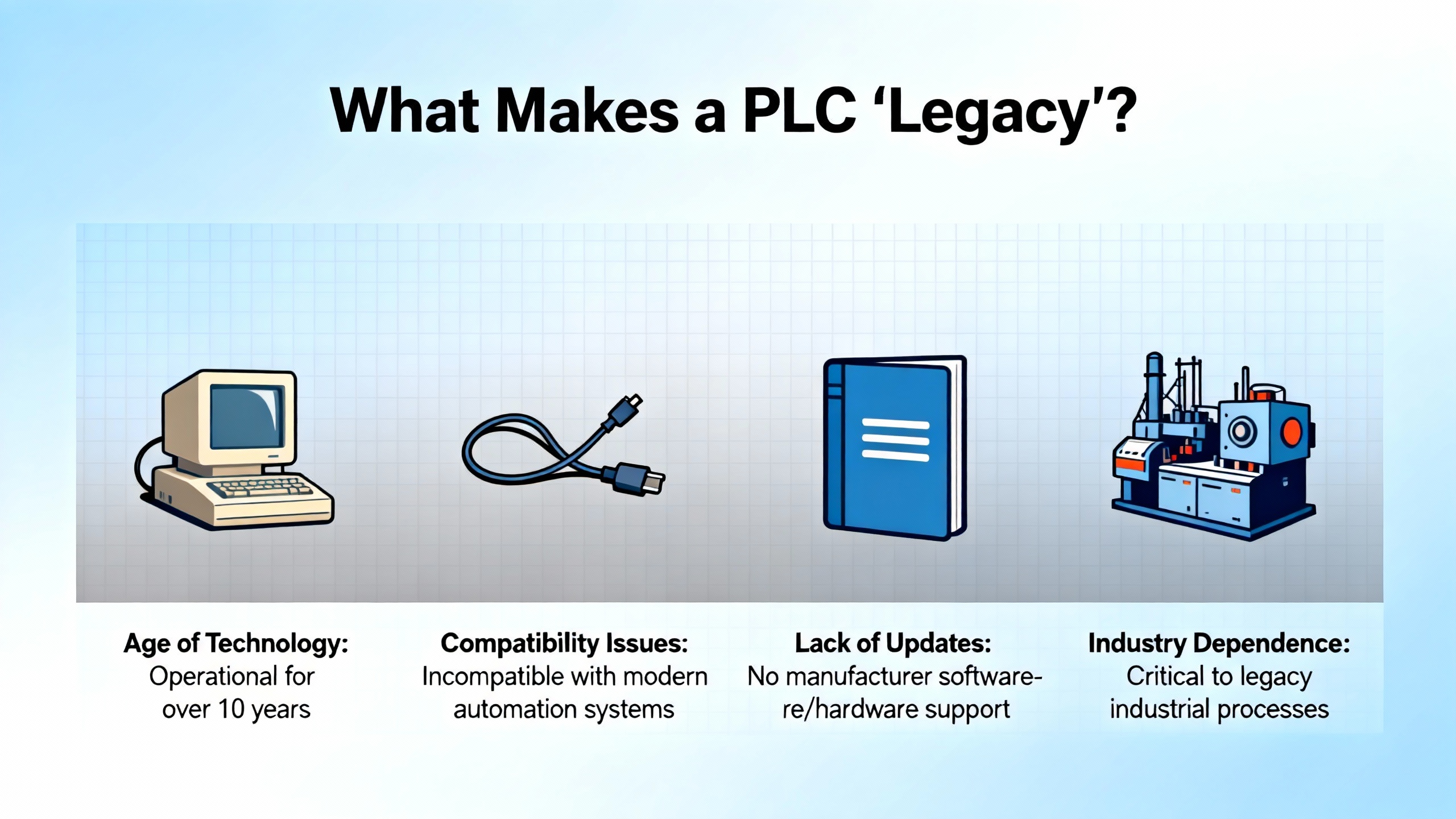

A PLC is the digital brain of an automated system. It reads inputs, executes logic, and drives outputs that operate breakers, contactors, inverters, motor drives, and mechanical equipment. A PLC becomes ŌĆ£legacyŌĆØ when the hardware, firmware, and software tools that support it are no longer evolving while the demands on the process keep increasing.

Industry notes from automation suppliers and integrators describe legacy PLCs with common symptoms. Hardware is decades old, processing power is limited, and memory and communication bandwidth are tight. Vendor support has ended or is close to end-of-life, including the programming environments. Spare parts are scarce or purchased from secondary markets. The engineering workforce that understands the platform is shrinking, so every retirement takes tribal knowledge with it.

Applied Manufacturing Technologies highlights classic platforms like PLC-5 and SLC 500 programmed with older environments and using networks such as DH+ or DeviceNet that are now hard to support. Balaji Switchgears emphasizes that legacy PLCs struggle with modern connectivity, have weak cybersecurity, and cannot easily participate in Industry 4.0 initiatives such as advanced diagnostics, data analytics, and remote monitoring. RT Engineering cites research estimating tens of billions of dollarsŌĆÖ worth of industrial automation assets at or beyond end-of-life.

From a power and reliability perspective, the PLC may still be connected to an old UPS or fed through panels that were never designed for todayŌĆÖs fault levels and harmonic content. The control system and the electrical system age together, and both become more fragile under disturbance.

Keeping a legacy PLC in place often feels like the conservative choice: ŌĆ£It is still working; letŌĆÖs not touch it.ŌĆØ The research and field experience tell a different story. HoneywellŌĆÖs work on legacy control migration describes three kinds of obsolescence that apply directly to PLC systems.

Technical obsolescence shows up as lost performance. The system cannot meet current production or power system control requirements, whether that means slower cycle times, limited data logging, or inability to coordinate with newer equipment such as modern UPS systems or digital protective relays. Functional obsolescence means missed opportunities, such as not being able to capture detailed load profiles, integrate with energy management software, or implement advanced safety and interlocking strategies. Supply obsolescence occurs when you cannot get replacement CPUs, I/O modules, or communication cards, or when vendor support and security updates have ended.

Several sources point to additional risks. Legacy hardware and software do not receive cybersecurity patches and often run on outdated operating systems. That makes them vulnerable in connected environments, exactly where many plants are heading. Balaji Switchgears notes that spare parts and knowledgeable engineers are both becoming scarce, which turns every failure into an emergency redesign rather than a controlled maintenance event. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs PLC migration guidance shows that when plants wait too long, they often jump directly from ŌĆ£steady stateŌĆØ to ŌĆ£crisis upgradeŌĆØ after a single catastrophic failure.

Operationally, this translates into higher unplanned downtime, longer troubleshooting, and rising maintenance cost. RT Engineering describes how aging wiring, relays, and panels contribute to intermittent faults and nuisance trips. In power-critical facilities such as data centers, healthcare, and industrial plants with high-energy UPS and inverter systems, those control disturbances can cascade into power quality events, transfer failures, and costly outages.

Modern PLC platforms are not simply faster versions of the old ones. They are designed as integration hubs for real-time data, advanced control, cybersecurity, and connectivity. Schneider Electric describes new PLC families as ŌĆ£efficiency multipliers,ŌĆØ combining high-speed processing with enhanced data processing, cloud connectivity, and cybersecurity features. RockwellŌĆÖs Logix-based architectures and similar platforms from other major vendors move communication to Ethernet-based networks, which offer more speed, scalability, and native integration with SCADA and IIoT systems than older proprietary buses.

From the perspective of a power system specialist, several capabilities stand out.

Modern PLCs support rich diagnostics and time-stamped events. When you coordinate them with smart UPS systems, power meters, and protective relays, you can correlate process disturbances with voltage sags, transfer events, and breaker operations. That enables root-cause analysis instead of guesswork. Contemporary platforms integrate more easily with energy management software and plant historians, making it practical to monitor load behavior, UPS performance, and inverter efficiency continuously rather than after the fact.

Cybersecurity is another differentiator. Modern PLCs and their engineering suites support user authentication, role-based access control, encrypted communications, and better patching options. Honeywell emphasizes ŌĆ£defense in depthŌĆØ for control and safety systems, and similar principles apply to PLC networks. When your PLC layer and your networked UPSs, inverters, and protective devices all implement security standards such as ISA/IEC 62443 concepts, you reduce the risk that a cyber incident propagates into a power or safety event.

Finally, modern PLC architectures are built for flexibility. They can scale from a small panel controlling a single UPS-backed switchboard to plant-wide systems integrated with distributed control systems. They support modular expansion, open protocols, and simultaneous connection to SCADA, maintenance systems, and third-party analytics, allowing you to keep options open instead of locking into a dead-end platform.

There is no single ŌĆ£rightŌĆØ way to replace a legacy PLC system. The best choice depends on your risk profile, downtime tolerance, budget, and long-term strategy. The research notes describe several broad approaches, which can be combined as needed.

Direct replacement means swapping old PLC hardware with new, while preserving existing program structure and wiring. Balaji Switchgears describes this as replacing hardware but keeping the program architecture. Industrial Automation Co. and other suppliers focus on plug-and-play or direct-fit replacements that match the form factor, electrical ratings, and communication protocols of legacy parts, allowing engineers to ŌĆ£swap and startŌĆØ without rewriting proven logic or rewiring entire panels.

This strategy suits smaller systems and applications where downtime windows are very tight and the legacy logic is well understood. The advantages include lower initial cost, minimal disruption, and reduced validation time. The downside is that you usually do not take full advantage of the new platformŌĆÖs advanced features. Technical debt in the control logic remains, and future enhancements might still be constrained by old design choices.

From a power-system standpoint, direct replacement is often used when the PLC mainly supervises a UPS or switchgear system that must stay available. Engineers may stage a temporary maintenance bypass, keep the load on a redundant UPS, and hot-swap controllers using migration kits, while leaving all field wiring intact.

Phased migration is the strategy most often recommended for large or continuous operations. Balaji Switchgears, Contec, and Applied Manufacturing Technologies all describe forms of staged modernization. You begin by mapping the installed base and identifying critical PLCs, networks, and I/O. Then you replace hardware module by module or line by line, while keeping production running as much as possible.

Contec emphasizes replacing obsolete electronic hardware first while preserving wiring via adapters, including plug-in wiring bases and migration modules. Once the new hardware baseline is stable, teams can migrate and clean up control logic in a second phase. Schneider Electric and others highlight the value of software conversion tools and plug-and-play wiring adapters that avoid reconnecting hundreds of wires, which is often the most error-prone part of a migration.

For facilities with critical power systems, phased migration allows you to align PLC cutovers with planned electrical outages or UPS maintenance windows. You might, for instance, update the PLC that controls a switchboard transfer scheme during a scheduled power-down when loads are temporarily supported by alternate feeds or redundant UPS capacity. This approach reduces the risk of plant-wide downtime but requires careful coordination and clear documentation, because old and new systems temporarily coexist.

A comprehensive overhaul means replacing the entire PLC infrastructure and often related HMIs, communication networks, and panels. Balaji Switchgears notes that this approach demands higher upfront investment and more planning but delivers the strongest long-term benefits in scalability, integration, and future readiness. PanelmaticŌĆÖs guidance on full replacement highlights that you typically replace PLC hardware, power supplies, cabinets, and often HMIs, designing a modern architecture from the ground up.

HoneywellŌĆÖs work on distributed control systems makes a similar argument. When technical, functional, and supply obsolescence converge, a full migration can improve plant availability, flexibility, and energy efficiency while enabling advanced control around set points and better information flow. The same thinking applies to PLC-based control systems that sit at the heart of power generation, critical distribution, or large industrial processes.

In power-critical applications, a comprehensive overhaul is often justified when the control system upgrade cost approaches a significant fraction of building a new system and when mechanical or electrical infrastructure also needs renewal. Pattie Engineering offers a common rule of thumb in the machinery context: when a controls upgrade approaches roughly half the cost of a new machine and the underlying equipment is in poor condition, full replacement can be the better investment. For electrical systems, a similar logic applies when switchboards, wiring, UPS systems, and PLC controls are all nearing end-of-life.

In practice, many plants choose hybrid approaches that combine elements of direct replacement, phased migration, and partial overhaul. GrayMatter describes a project where a chemicals plant avoided an expensive move to a full DCS by upgrading the PLC platform while temporarily preserving the existing I/O system. This intermediate step reduced risk and disruption. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs case studies show the use of modernization kits and adapters that let new PLCs work with old wiring and even existing HMIs initially.

Communication gateways are another form of bridge. Applied Manufacturing Technologies discusses replacing DH+ and DeviceNet with Ethernet/IP while providing compatibility paths so legacy devices can continue operating during transition. Contec points out that even details such as connector replacement can be deferred to later maintenance windows to get production back online faster.

Hybrid strategies are particularly useful when PLCs are tightly integrated with power infrastructure. For example, you can upgrade the PLC and network that coordinate UPS systems and breakers, while leaving field wiring and metering in place, and then later roll in new digital relays or meters once the controls backbone is stable.

The following table summarizes the main strategies.

| Strategy | Typical Use Case | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct replacement | Small systems, tight downtime windows | Low disruption, reuses logic and wiring | Limited access to advanced features, technical debt remains |

| Phased migration | Large or continuous operations | Manages risk and downtime, allows learning | Longer overall timeline, mixed-platform complexity |

| Comprehensive overhaul | Severely obsolete or growth-constrained systems | Maximum flexibility, performance, and integration | Highest upfront cost and planning effort |

| Hybrid/bridge approaches | Complex brownfield environments | Balances risk and benefit, protects investments | Requires careful engineering and governance |

Modernizing a legacy PLC system becomes much more manageable when you treat it as a lifecycle and risk-management exercise rather than a one-time hardware purchase. Several sources converge on a set of best practices that align well with reliability engineering principles.

Schneider Electric stresses that successful migration starts with a comprehensive site assessment. Applied Manufacturing Technologies advises beginning with a full inventory of installed PLCs, wiring, I/O lists, networks, and programs. Contec and RT Engineering echo the need to map the installed base and identify obsolete or high-risk components.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs viewpoint, this assessment should also cover power supply to the control system. Document how each PLC, HMI, and network switch is powered, which ones are backed by UPS units or inverter feeds, and which depend on raw utility or generator sources. Note any history of nuisance trips tied to power disturbances, as well as known weaknesses in grounding and bonding.

Once you have a clear inventory, prioritize systems based on criticality and risk. Applied Manufacturing Technologies recommends a criticality and risk assessment that considers operational importance and the impact of potential failures. Honeywell frames this in terms of total cost of ownership: compare the cost and risk of keeping the legacy system against the cost and benefit of migration. Systems that protect life safety, power continuity, or major production throughput should move to the top of the list.

Balaji Switchgears and SwimmŌĆÖs application modernization guidance both highlight the importance of clear objectives. Decide whether you are aiming primarily to improve reliability, add new capabilities, strengthen cybersecurity, reduce maintenance cost, support expansion, or all of the above. Omron notes that short-term production metrics can make teams reluctant to upgrade unless they see how it will improve their key performance indicators, such as uptime, scrap rate, or maintenance response time.

For power and controls projects, include objectives that directly tie to the electrical system. Examples include reducing transfer failures between sources, improving visibility into UPS runtime and inverter loading, adding better alarming around power-quality events, or aligning with safety standards such as NFPA 79, ISO 13849, and IEC 61508 as appropriate. The more clearly you articulate these goals, the easier it is to justify budget and select the right technical approach.

Platform selection should prioritize long-term support, open standards, and compatibility with your existing SCADA, MES, and power monitoring systems. Contec advises choosing platforms that support open protocols and can scale with future requirements. Panelmatic points to vendor ecosystems that align with UL, CSA, NEC, and similar standards.

Applied Manufacturing Technologies and PLCDepartment show how modern Rockwell and other major vendor platforms use Ethernet/IP and Studio 5000-style environments to provide higher speed, memory, and easier integration. HoneywellŌĆÖs DCS roadmap illustrates the value of vendor migration kits and tools that protect prior investments while enabling new functionality.

Architecturally, you should plan for a network that supports high availability and secure segmentation. Many successful projects move from older copper-based networks to fiber-based rings or redundant Ethernet topologies, as in the ConsultingŌĆōSpecifying Engineer case study of a water treatment plant. This not only improves performance and resilience but also aligns better with the needs of modern UPS monitoring, digital relays, and power meters that speak Ethernet-based protocols.

From a power-systems perspective, architecture decisions include how you separate and protect control power. Critical PLCs and networking equipment should be fed from appropriately sized and coordinated UPS systems, with clear separation from high-noise inverter outputs and motor loads, and with attention to grounding and surge protection.

Multiple sources warn against underestimating the scope and downtime of PLC migrations. Omron points out that motion-control upgrades often turn into full machine replacements when documentation and commented code are missing. Applied Manufacturing Technologies and Contec both recommend phased cutovers, weekend swaps, or running shadow systems to minimize production impact.

Testing and simulation play a central role. Contec recommends pre-cutover testing using staging environments or simulation tools to validate new logic and I/O mappings. Panelmatic emphasizes factory acceptance testing before installation, while CSE-focused articles describe functional, performance, and user-acceptance testing as critical steps. GrayMatterŌĆÖs project demonstrates the value of building and testing intermediate configurations before final cutover.

Safety has to remain at the core of the project. Omron recommends treating major upgrades as effectively new machines and performing formal safety audits. RL Consulting underscores routine safety-function tests, proper panel design, and alignment with standards. During cutover, that means clear lockout/tagout procedures, manual control plans when automation is temporarily offline, and cautious commissioning sequences so that power equipment, UPS transfers, and breaker operations are never left in ambiguous states.

Power quality can make or break a PLC replacement project. Even a perfectly engineered control system will misbehave if it is fed from unstable or poorly protected sources. While the research notes focus on controls, field experience in power supply systems suggests a few practical principles.

First, review the control power architecture alongside the PLC design. Confirm that key PLCs, communication switches, and HMIs are backed by reliable UPS units or inverter-backed supplies with enough runtime to cover planned cutovers and unexpected delays. Reinforce any weak links, such as small unmonitored UPS units hidden in panels or aging batteries.

Second, coordinate protection and grounding. When you introduce new PLC power supplies and network equipment, verify that surge protection and grounding schemes remain effective. This is particularly important when tying into inverter outputs or generator-backed buses, where voltage transients and harmonics can be more pronounced.

Third, use the migration as an opportunity to instrument power events. Modern PLCs can log loss-of-power and brownout events more precisely, and when combined with networked UPSs and power meters, they allow you to build a much clearer picture of how the power system and control system interact during disturbances. That data is valuable for future tuning and for justifying further power-quality investments.

Finally, do not overlook selective coordination between breakers feeding PLC panels, UPS systems, and large loads. A well-designed power system ensures that faults clear locally without dropping the entire control backbone.

Several sources, including Contec, Panelmatic, Schneider Electric, and Honeywell, agree that thorough testing and training are key to safe, low-risk migrations. Before touching production, test converted logic in a lab or staging environment. Verify communication with all devices, including UPS monitoring interfaces, protective relays, and drives.

Training deserves the same attention. Schneider Electric emphasizes building a balanced migration team that includes people with deep knowledge of both legacy and new systems. Operators, maintenance technicians, and engineers all need to understand the new tools, HMIs, alarms, and recovery procedures. In many plants, the first major failure after migration doubles as a training exercise. A better approach is to simulate faults and rehearsed responses before the system is put in charge of critical loads.

Upgrading legacy PLCs without addressing power protection is a missed opportunity. Many of the worst failures I have seen happen when a marginal control system meets a marginal power system during a disturbance. The PLC trips on a voltage sag, the UPS or inverter does not respond as expected, and the system falls back to manual workarounds.

Modern PLC platforms and modern UPS and inverter systems together can significantly raise resilience. When your PLC can read UPS status, bus voltages, and breaker states in real time, you can implement intelligent load shedding, controlled shutdowns, and safe transfer sequences. When your UPS and power protection gear provide detailed alarms and event logs, the PLC can react more gracefully and drive more useful diagnostics to operators.

As you plan a PLC migration, treat the power system as a first-class stakeholder. Include UPS replacement or battery refresh in the project scope where necessary. Confirm that new PLC power supplies are compatible with the UPS topology and that inrush currents or transformer magnetizing currents will not upset the protection scheme. Verify that inverter-based sources are coordinated with the new control logic, especially where synchronization, transfer, or generator startup logic depends on PLC decisions.

This integrated view of controls and power is where many plants unlock the most value from modernization. The same investment that retires a legacy PLC can also tighten safety interlocks on switchgear, improve visibility of UPS performance, and reduce the frequency and duration of power-related incidents.

The research notes and field projects highlight several recurring pitfalls that you can avoid with awareness and planning.

One pitfall is underestimating downtime and project scope. Applied Manufacturing Technologies and CSE-focused authors both describe projects where teams assumed small scope and then discovered wiring errors, communication issues, or logic differences that added days to commissioning. Omron points out that unresolved technical debt in code and documentation can cause motion-control upgrades to expand into full machine replacements.

Another pitfall is working from incomplete documentation. RT Engineering and RL Consulting emphasize that many legacy systems lack accurate schematics, I/O lists, or commented code. That makes it difficult to map behavior from old to new hardware and increases the risk of subtle errors. A thorough documentation effort during assessment pays off later when troubleshooting and training.

A third common mistake is skipping a rigorous network evaluation. Applied Manufacturing Technologies warns against ignoring the underlying network when moving from older buses to Ethernet-based architectures. Without careful design of addressing, segmentation, and redundancy, new systems can inherit or worsen communication bottlenecks.

A fourth issue is attempting a big-bang conversion on a large system without intermediate stages or rollback options. Contec, Honeywell, and SwimmŌĆÖs modernization guidance all favor incremental, risk-managed approaches such as phased migration or strangler patterns. While a one-time cutover can work in some contexts, it demands exceptional preparation and carries high risk.

Finally, many projects underinvest in training and change management. Schneider Electric emphasizes building a balanced team and involving maintenance and operations early. When staff are not comfortable with new platforms, they tend to distrust alarms, bypass protections, or revert to unsafe manual practices under stress. Building training and coaching into the project plan reduces that risk.

Not every legacy PLC needs immediate replacement. The decision should balance risk, cost, and strategic direction. DoSupplyŌĆÖs work on pros and cons of upgrading legacy PLCs recommends a formal lifecycle and risk assessment that considers vendor support status, spare availability, failure history, cybersecurity exposure, and process criticality.

In some low-risk or isolated systems with stable operation and reliable spares, it can be reasonable to extend life through good maintenance, selective retrofits, and stocking of critical components. RL Consulting notes that structured PLC maintenance and selective retrofits can extend machinery life without full replacement.

However, as HoneywellŌĆÖs control system migration guidance points out, you should compare the full cost of maintaining the legacy systemŌĆöincluding escalating downtime risk, difficulty sourcing parts, and lost opportunitiesŌĆöwith the cost and benefit of migration. Application modernization studies show that in many organizations, a large share of budgets goes into keeping old systems alive rather than building new capabilities.

Pattie EngineeringŌĆÖs rule of thumb about upgrade cost relative to new equipment cost is helpful. When a controls upgrade starts approaching a substantial fraction of full replacement and the mechanical or electrical infrastructure is also aging, full replacement deserves serious consideration. In power-critical environments, the threshold for action may be even lower, because the consequence of a major failure is significant.

Direct replacement works best when the existing logic is fundamentally sound, the system is relatively small, and your main concern is hardware obsolescence rather than functionality. Comprehensive overhauls make sense when you need new capabilities, better integration, and a long planning horizon, or when multiple forms of obsolescence are present at once. Phased and hybrid strategies let you start with lower risk and expand scope over time.

Involve them from the assessment phase. The power system supplies the control system, and the control system governs power equipment. Decisions about PLC architecture, panel design, and cutover windows all affect UPS loading, breaker coordination, and safe switching sequences. Early coordination helps avoid surprises such as control power being lost during a critical transfer or UPS runtime being insufficient for commissioning delays.

In many cases you can. Vendors such as Schneider Electric and Rockwell provide code conversion tools and migration kits that preserve existing logic while moving it to new platforms. Suppliers like Industrial Automation Co. focus on drop-in replacements that minimize logic changes. However, Contec and others suggest using migration as an opportunity to clean up and modularize code, especially in smaller systems where the cost of improvement is manageable.

The most important first step is a structured assessment and prioritization. Inventory all PLCs, networks, and power supplies; document their condition and support status; and then rank them by criticality and risk. This allows you to build a phased roadmap that fits budget and downtime constraints, rather than reacting to the next unexpected failure.

Upgrading legacy PLC systems is one of the most effective ways to protect the reliability of modern industrial and commercial power systems. When you treat the PLC migration as part of a broader strategy that includes UPS, inverters, power quality, safety, and cybersecurity, you turn a looming risk into an opportunity: a more resilient, observable, and future-ready plant that can withstand both electrical and operational disturbances with confidence.

Leave Your Comment