-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In most commercial and industrial buildings, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning are among the largest electrical loads. Facility and building automation providers consistently report that HVAC often draws close to half of a buildingŌĆÖs total energy. That means your thermostats and controllers are not just comfort devices; they are front-line energy management tools.

Honeywell controllers and thermostats sit squarely in this control layer. Used well, they turn mechanical equipment into a responsive, efficient climate system. Used poorly, the same hardware drives up energy bills, shortens equipment life, and generates constant hotŌĆōcold complaints.

Speaking as a power system and reliability specialist, I tend to look at HVAC controllers the way I look at UPS systems or inverters: they are relatively small investments that govern very large amounts of energy and equipment stress. The rest of this article walks through how HVAC controls work, where Honeywell-style controllers fit, and how to use them to improve climate control, energy performance, and reliability.

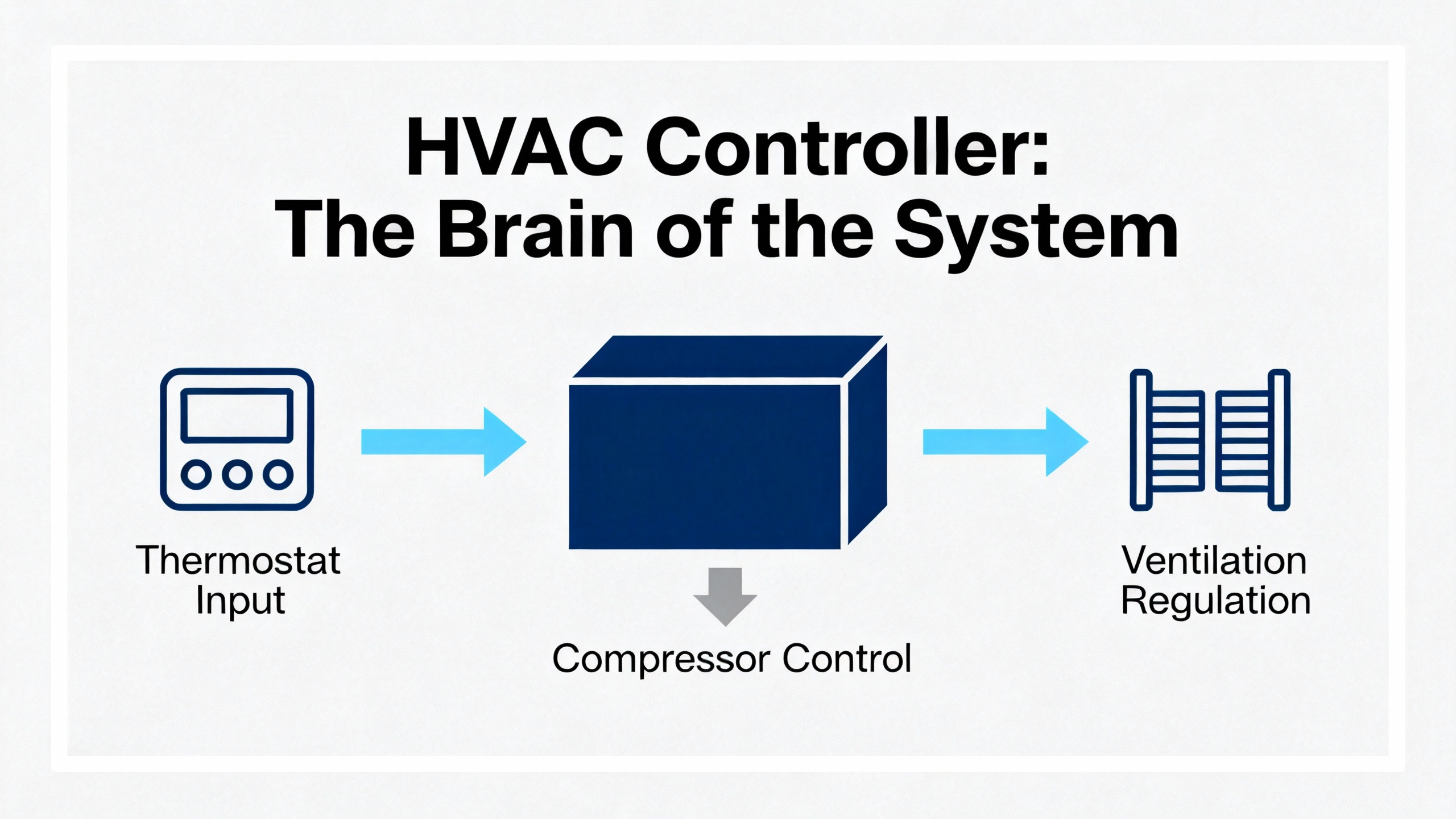

HVAC systems control temperature, humidity, airflow, and indoor air quality by moving and conditioning air between indoors and outdoors. Industry resources describe the control layer as the ŌĆ£brainŌĆØ of this system. It processes sensor information and commands the equipment that actually heats, cools, and ventilates.

Across the research, a basic control architecture always contains four elements. Sensors measure conditions such as temperature, humidity, pressure, or airflow. A controller or thermostat compares those measurements with setpoints and applies decision logic. Controlled devices such as compressors, fans, valves, and dampers execute the commands. An energy source, almost always electricity in commercial buildings, powers both the controls and the HVAC equipment.

Controls operate as a loop. Sensors feed data into the controller. The controller decides whether to start, stop, or modulate equipment. Actuators carry out that decision, and the resulting temperature or airflow changes are sensed and fed back to the controller. In small systems, that ŌĆ£controllerŌĆØ may be a single wall thermostat. In larger facilities, it is usually a network of digital controllers tied into a Building Automation System.

Effective control has two parallel goals. First, it must maintain thermal comfort, which depends not only on air temperature but also humidity, air speed, radiant temperature, clothing, and activity levels. Second, it must meet that comfort target with minimal wasted energy. Sources that focus on smart HVAC controls note that efficient systems with well-designed controls can cut HVAC energy use by roughly 20 percent or more compared to poorly controlled systems.

Because HVAC can consume nearly half of a buildingŌĆÖs energy, those control decisions ripple through your entire electrical and mechanical infrastructure. That is why controller selection, configuration, and maintenance deserve the same attention you might give to a main switchboard or a central UPS.

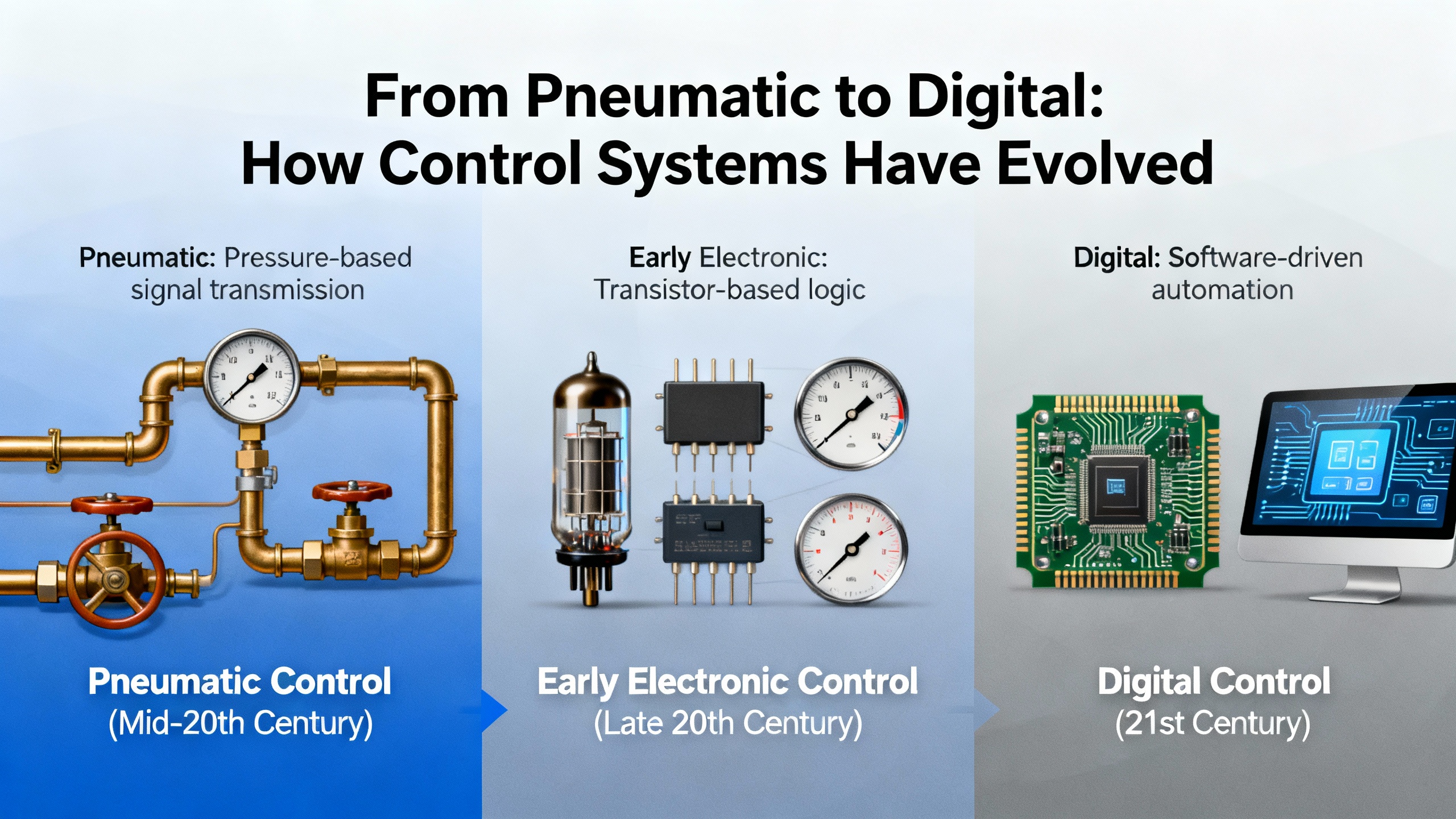

To understand where Honeywell controllers and thermostats fit today, it helps to know the three main families of HVAC control systems described in modern controls literature: pneumatic, analog electronic, and direct digital control.

Pneumatic controls rely on compressed air as the signaling medium. They send variable air pressure through small tubes to modulate valves and dampers. Historically, this was the dominant technology in commercial buildings because it was relatively inexpensive and simple to install and maintain.

The trade-off is accuracy and flexibility. Sources on HVAC controls describe pneumatic systems as less precise than modern electronic controls, even though careful calibration can improve them. Many new projects no longer install pneumatic controls; they survive mainly in older facilities that have not yet been upgraded.

Analog electronic controls use low-voltage electrical signals to switch equipment on and off or to modulate it in a limited way. In residential and small commercial buildings, this is still common: a basic digital thermostat sends a simple on/off signal to a furnace or rooftop unit.

Technical guides point out that these controllers are more accurate than pneumatics and easier to troubleshoot but often still limited. They typically operate equipment at either full load or off, and they struggle to implement more advanced strategies such as variable capacity, dynamic reset schedules, or multi-zone coordination. For a single rooftop unit serving a single open-plan office, that may be acceptable. For a complex building, it is not.

Direct digital control systems replaced analog signaling with microprocessor-based controllers. These devices digitize sensor inputs, apply software algorithms, and drive actuators and relays through programmable logic. Building controls experts note that DDC is now the most widely used approach in modern facilities.

DDC shines in three areas. First, it can modulate fans, pumps, and valves with much finer resolution, enabling strategies like supply air temperature reset or variable static pressure control. Second, it supports zoning and multi-zone coordination, which is essential in larger buildings that combine different uses and occupancy patterns. Third, it can communicate over digital networks, enabling integration into a Building Automation System and support for open protocols such as BACnet or Modbus.

Pneumatic and analog controllers still exist, often side by side with digital upgrades. But from an energy-management and reliability standpoint, DDC is the foundation on which smart HVAC control, analytics, and modern Honeywell-style controllers operate.

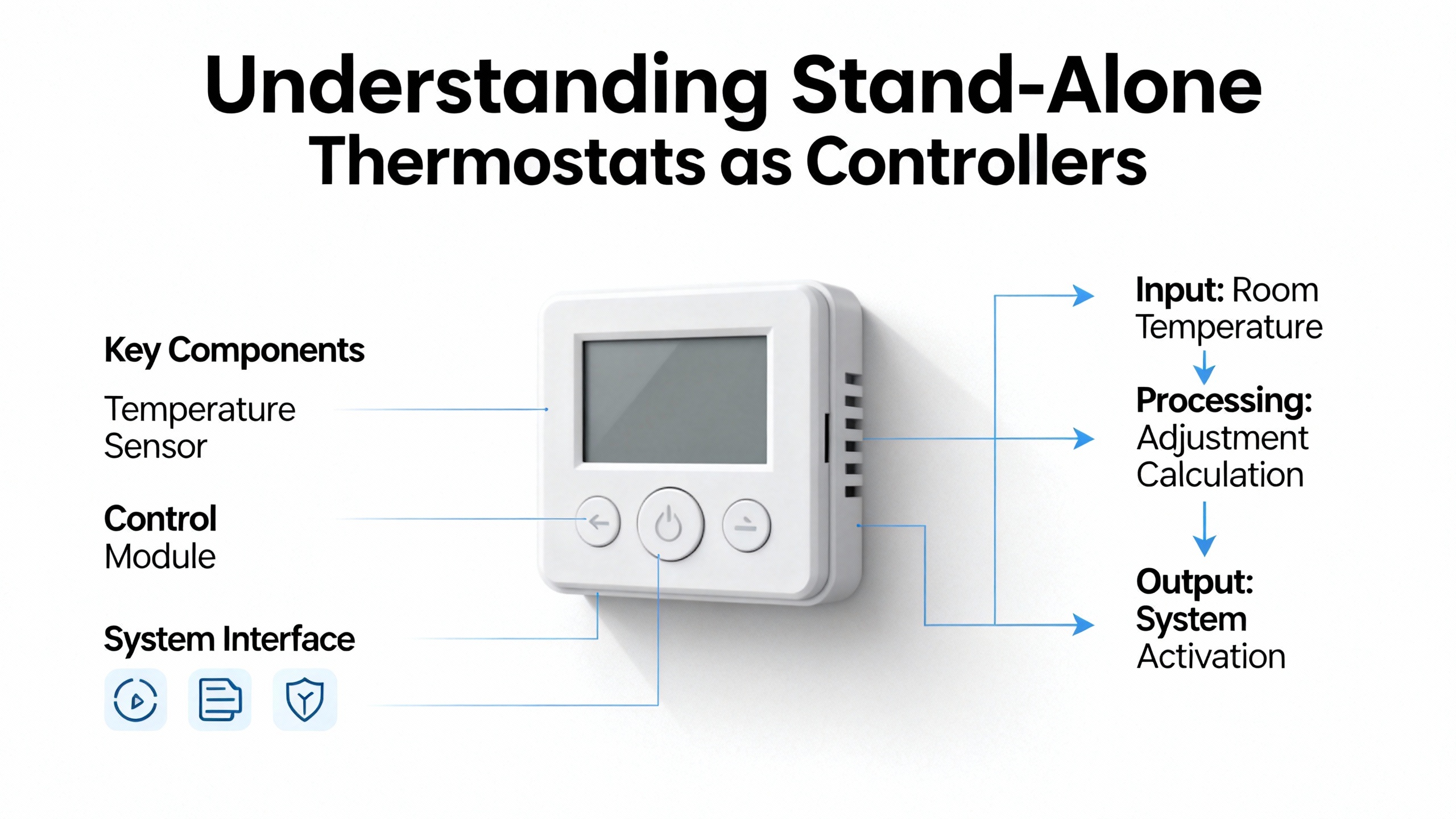

Not every building needs a full Building Management System. Many small and mid-size facilities rely on stand-alone controllers and thermostats to manage temperature and, in some cases, humidity and air quality. Controls specialists define stand-alone controllers as devices that operate without a central BAS, directly controlling local HVAC equipment. They are especially useful in smaller buildings or remote sites where centralized control is impractical, though they can become hard to scale in large, complex systems.

Within this category, thermostats are the most visible ŌĆ£controllerŌĆØ the occupants see. Technical overviews divide thermostats into three main types, and the research notes give specific examples where Honeywell devices fit into that landscape.

Basic on/off digital thermostats simply switch equipment at a set threshold. When the room temperature drifts above or below the setpoint, they close or open contacts to start or stop heating and cooling. A Honeywell Pro Non-Programmable Digital Thermostat is used in the field as an example of this class: a straightforward device focused on local temperature control without built-in scheduling or analytics.

Programmable thermostats add time-based schedules. According to control-system guides, they follow fixed programs set by the user, such as one schedule for weekdays and another for weekends. They let you align temperature setbacks with occupancy patterns, reducing runtime and energy use when spaces are unoccupied.

Smart thermostats go further. Sources that compare programmable and smart models describe several common features: learning capabilities that adapt to occupant behavior, remote internet access via apps, energy-use reporting, and integration with smart-home platforms. They often support more advanced control modes such as occupancy-based setbacks or geofencing.

Multi-zone thermostats are a special subset. They manage different areas independently, usually using wireless room sensors. The Honeywell Home T9 WiFi with room sensors is cited in the research as an example of a multi-zone thermostat. Devices in this class allow a single controller to coordinate comfort across several rooms or small zones, which is a bridge between a simple stand-alone thermostat and a full-blown BAS.

To summarize the differences in practical terms, consider the following comparison.

| Controller Type | Example Device | Key Characteristics | Typical Use in Buildings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic digital thermostat | Honeywell Pro Non-Programmable Digital Thermostat | Simple on/off control at a set temperature with local buttons and display; no schedules or advanced energy features | Single-zone spaces with predictable occupancy and stable operating hours |

| Programmable thermostat | Typical 7-day programmable thermostat | Follows user-defined schedules by time of day and day of week; enables temperature setbacks during unoccupied periods | Offices or small facilities with regular occupancy patterns seeking basic energy savings |

| Smart multi-zone thermostat | Honeywell Home T9 WiFi with room sensors | WiFi connectivity, app-based remote control, room sensors for multi-zone management, and advanced scheduling or occupancy-based control depending on configuration | Small to mid-size buildings or suites needing flexible schedules, multiple comfort zones, and visibility into usage |

Control-system specialists highlight several pros and cons around these options. Basic thermostats are inexpensive, intuitive for occupants, and lack complex features that can be misconfigured. The trade-off is that they provide little active energy management beyond a fixed setpoint. Programmable thermostats introduce significant savings potential by matching operation to occupancy, but someone must design and maintain the schedules, and they do not adapt on their own.

Smart and multi-zone thermostats cost more and may require additional wiring or configuration. However, research on smart HVAC controllers notes that these devices, when used correctly, can reduce HVAC energy consumption and bills by roughly 10 to 40 percent through more precise, occupancy- and weather-based control. They also provide the kind of remote visibility and analytics that facility managers increasingly expect.

As a reliability advisor, I often see the most value when basic Honeywell thermostats in critical areas are upgraded to smart or multi-zone models with carefully designed schedules. That can deliver meaningful energy savings and better comfort with relatively modest project scope, especially in buildings that are not yet ready for a full BAS.

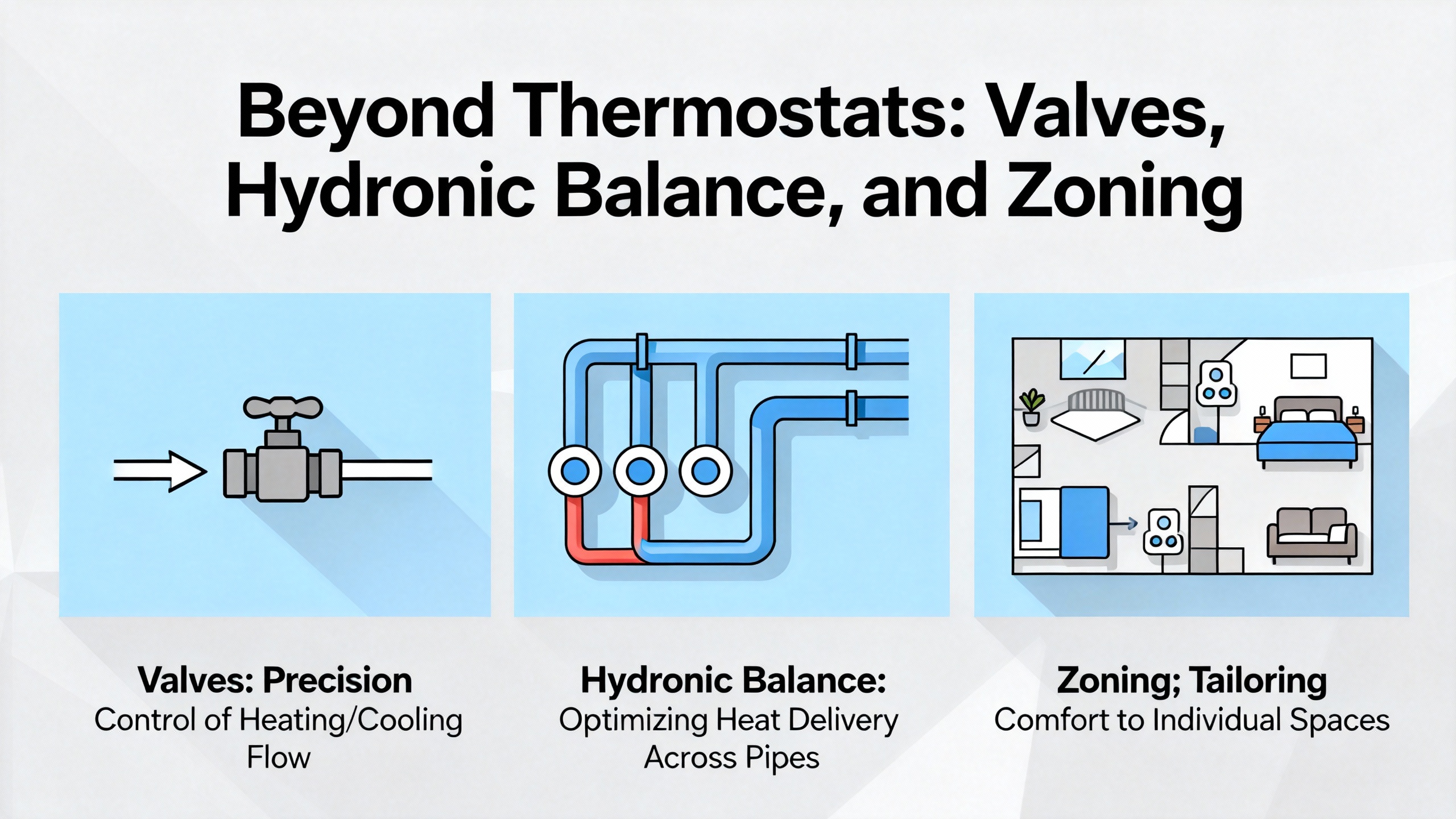

Controllers do more than read a temperature and toggle a compressor. They also manage water flow and air distribution, which is where much of the real-world comfort and efficiency is gained or lost.

Controls-focused resources describe several stand-alone flow controllers commonly used in HVAC hydronic systems. Temperature Control Valves adjust water flow based on temperature to maintain setpoints in coils or zones. Pressure-Independent Control Valves keep the correct flow even when system pressure fluctuates. Automatic Balancing Valves distribute flow evenly across branches without constant manual adjustment.

These devices work hand in glove with the concept of hydronic balancing, which HVAC balancing specialists define as ensuring hot or chilled water is evenly distributed so each area receives the correct amount of thermal energy. When balancing is neglected, buildings develop hot and cold spots, and central equipment runs harder to compensate. Proper balancing improves comfort, reduces wasted energy, and extends equipment life by avoiding chronic overwork.

On the air side, zoning is just as important. Zoning divides a building into separately controlled climate areas, each with its own sensor or thermostat. Technical articles on multi-zone HVAC emphasize that this allows targeted conditioning based on occupancy and use patterns, improving comfort and energy efficiency. In larger buildings, this is often orchestrated by DDC controllers and a Building Management System. In smaller buildings, multi-zone thermostats like the Honeywell Home T9 can provide a light-weight zoning solution by blending local sensing and central scheduling.

The key lesson is that temperature control, airflow, and water flow must work together. Simply installing a new thermostat without addressing duct leaks, valve settings, or balancing often leaves most of the potential savings on the table.

In many modern facilities, HVAC controls do not operate in isolation. Instead, they connect into a Building Automation System. Controls manufacturers and integrators describe a typical BAS architecture in four layers: a head-end computer or energy management software, network infrastructure, distributed controllers, and end devices.

The head-end is the central user interface where operators view trends, alarms, and schedules. Network infrastructure, often Ethernet for head-end and controller communication plus RS-485 for field buses, connects everything together. Field controllers run the specific heating, cooling, and ventilation sequences for air handlers, rooftop units, boilers, chillers, and terminal units. End devices like sensors, relays, and actuators physically interact with the HVAC equipment.

HVAC control logic usually follows a priority hierarchy. For example, operator commands override logic programming, which in turn overrides weekly schedules. That hierarchy ensures that emergency or manual commands can temporarily trump automated behavior when necessary, without permanently breaking the underlying logic.

Experts on HVAC integration emphasize the role of communication protocols. Open protocols such as BACnet and Modbus allow devices from different vendors to exchange data, which is essential for multi-vendor integration and system-wide optimization. Proprietary protocols can create interoperability barriers and complicate tasks such as energy reporting or fault analytics.

Smart HVAC gateways and cloud-based management suites, as described by multi-brand control vendors, address this by providing a unified interface for remote monitoring and control, real-time fault alerts, predictive maintenance, and exportable reports. These platforms are particularly valuable for organizations managing multiple buildings or brands.

Stand-alone controllers and Honeywell-style thermostats fit into this picture in two main ways. First, they can serve as the primary control devices in smaller buildings with no BAS, delivering local control and energy management. Second, many stand-alone controllers can later be integrated into centralized systems using additional hardware and professional setup. Modern smart controllers often support smart-home or IoT platforms such as voice assistants, and in larger buildings they may be bridged into a more comprehensive BAS.

From a power and reliability perspective, the decision is less about brand and more about architecture. DDC-based, interoperable control systems combined with good zoning, advanced scheduling, and analytics provide the best long-term path to lower energy costs and more stable operations.

Energy-efficiency specialists define HVAC efficiency as delivering acceptable temperature, humidity, ventilation, and indoor air quality with minimum energy input. Standards from groups such as ASHRAE and codes such as the International Energy Conservation Code and Uniform Mechanical Code set minimum baselines for design and performance. The U.S. Department of Energy sets appliance-level rules and, from January 1, 2023, introduced updated metrics like SEER2, EER2, and HSPF2 for residential units to better reflect real operating conditions.

Even with efficient equipment, the control layer is where most day-to-day savings are realized. Several research sources give a consistent picture of how controllers contribute.

First, basic efficiency metrics such as SEER (Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio), EER (Energy Efficiency Ratio), and HSPF (Heating Seasonal Performance Factor) describe equipment performance as the ratio of cooling or heating output in British Thermal Units to electricity input in kilowatt-hours. Higher ratings indicate more efficient equipment. However, actual energy use depends heavily on how often and how long that equipment operates, which is exactly what controllers govern.

Smart control providers report that efficient HVAC systems with good controls can consume up to around 20 percent less energy than similar systems without effective control strategies. Another analysis of smart HVAC controllers for commercial buildings estimates that these devices can reduce HVAC energy consumption and bills by roughly 10 to 40 percent through features such as remote monitoring, automated scheduling, occupancy-based control, and integration of weather data.

Controls also interact with physical system upgrades. Ductwork is a prime example. Industry organizations cited in ductwork installation guidance, such as SMACNA and OSHA, note that defective duct systems can cause up to 40 percent energy loss, and the U.S. Department of Energy has reported that effective duct sealing and insulation can improve energy efficiency by up to about 20 percent. Other HVAC sources estimate leaky ductwork can waste roughly 30 percent of conditioned air, particularly in attics and crawl spaces. Controllers cannot fix a leaking duct, but once ducts are sealed and balanced, they can reduce fan speeds, reset static pressure setpoints, and shorten runtime to lock in the gains.

Advanced control strategies on air handling units, chillers, and boilers can deliver additional savings. Analytics-focused HVAC research shows that well-designed and tuned control algorithms, such as supply air temperature and pressure control, use of free-cooling modes, and water temperature reset strategies, can reduce HVAC energy consumption by up to about 30 percent. These strategies depend on DDC controllers and, in larger systems, a BAS or equivalent management platform.

Preventive maintenance is the third leg of the stool. Detailed maintenance studies highlight specific tasks and their typical energy impact. Regular air filter replacement can yield on the order of 5 to 15 percent savings by preserving airflow. Annual thermostat calibration can avoid a 2 to 3 percent penalty from over- or under-conditioning. Duct inspection and sealing every few years can save up to about 20 percent in some buildings. Cleaning condenser and evaporator coils annually can capture up to 30 percent savings by restoring heat transfer. Annual refrigerant checks, blower cleaning, electrical connection checks, and system controls checks each contribute smaller but meaningful savings, often in the single- to mid-double-digit percent range.

The recommended practice from maintenance research is clear. Pair annual professional maintenance, including control-system checks, with simpler monthly or quarterly tasks such as filter checks and basic inspections. That combination strikes the best balance between maintenance cost and energy savings across most climates and system ages.

When you place Honeywell controllers or other smart thermostats into that context, they become one piece of a larger optimization strategy. The biggest gains come when control upgrades, duct sealing, hydronic balancing, and preventive maintenance are coordinated rather than treated as separate projects.

Energy savings are important, but from a power-systems perspective, reliability is just as critical. Several themes emerge from HVAC troubleshooting and maintenance guides that are directly relevant to controllers and thermostats.

First, regular maintenance of the overall HVAC system improves reliability and extends equipment life. Providers working in variable climates report that tasks such as filter changes, control checks, and coil cleaning reduce unexpected breakdowns and keep systems operating efficiently. Annual professional inspections are widely recommended, with more frequent service in harsh or extreme climates.

Second, controls themselves require maintenance and updates. Guidance on HVAC control systems stresses keeping thermostat or BAS software and firmware up to date, scheduling routine control-system checkups, and verifying that sensor placement remains correct. Controls experts highlight sensor location as especially critical: a temperature sensor placed in direct sunlight or near a poorly insulated exterior wall can mislead the controller, leading to chronic comfort complaints and wasted energy.

Third, troubleshooting skills increasingly revolve around controls and automation. Technical resources aimed at HVAC technicians emphasize understanding thermostats, sensors, actuators, and digital protocols, as well as the ability to read wiring and control logic diagrams. Many HVAC failures trace back to electrical or control issues rather than purely mechanical faults. A structured troubleshooting approach usually starts with basic checks: thermostat settings, power supply, visible wiring condition, and obvious airflow issues. Only then does it move to deeper diagnostics with multimeters, gauges, and software tools.

Fourth, installation quality has a long-term reliability impact. Installation-focused articles warn that improper sizing, poor ductwork, skipped safety steps, and incorrect refrigerant charge increase repairs, energy use, and downtime, costing businesses thousands of dollars over a systemŌĆÖs life. Standards such as ASHRAE 90.1 and requirements from agencies like the EPA for refrigerant handling exist precisely to reduce these risks. Thorough testing and calibration at startup, including thermostat and controller verification, help catch issues before they become recurring service calls.

Finally, there is a practical limit to do-it-yourself work. Homeowner-oriented troubleshooting guides are explicit: internal repairs, control-board work, complex wiring, and refrigerant tasks should be left to licensed technicians. The same caution applies in commercial settings. Simple thermostat battery changes or setpoint adjustments are reasonable for on-site staff. Replacing or reprogramming controllers that interact with larger DDC networks or affect safety interlocks is not.

In my own work on power and reliability projects, I have seen that neglected HVAC controls often show up indirectly as power quality complaints: frequent compressor starts, unexpected demand peaks, or nuisance trips during extreme weather. When technicians clean up schedules, calibrate sensors, and tighten up control logic, those electrical symptoms frequently diminish. Good controls are not just about comfort; they help flatten the load profile and reduce avoidable stress on upstream electrical infrastructure.

Designing a control strategy that uses Honeywell thermostats and controllers effectively starts with a clear view of your building, not a catalog of devices.

Begin by understanding how your spaces are used. Control-system guidance repeatedly stresses that system selection should weigh energy efficiency, correct sizing, upfront cost, and long-term savings. For a single open office or a small retail store with stable hours, a well-chosen digital or programmable thermostat may be sufficient. For a medical office, school, or mixed-use facility with varied occupancy patterns, smart multi-zone thermostats or distributed DDC controllers tied to a BAS might be more appropriate.

Next, match controller type to your operational needs. If your primary goal is to stop occupants from overriding setpoints and running equipment overnight, a programmable thermostat with locked schedules might be enough. If you want detailed energy reporting and the ability to adjust settings from your cell phone when issues arise after hours, smart thermostats with remote access and energy-use analytics are a better fit. Multi-zone thermostats such as the Honeywell Home T9, with their room sensors, are well suited when a single rooftop unit serves several rooms with different loads and occupancy patterns.

Compatibility is non-negotiable. Control-system references emphasize confirming that any thermostat or controller will work with the existing HVAC equipment and control wiring. Smart thermostats often require a common power wire and may need professional installation. In more complex systems with zoning dampers, variable speed equipment, or hydronic loops with specialized valves, it is wise to involve a qualified HVAC contractor or controls specialist early.

Ease of use is another selection factor that shows up across multiple sources. A user interface that building staff can understand and manage is worth as much as an advanced feature list that no one touches. Controllers with clear scheduling screens, intuitive setpoint adjustments, and understandable alarms reduce the risk of ŌĆ£set and forgetŌĆØ behavior that undermines potential savings.

Think also about integration and future growth. Stand-alone controllers offer the advantage of flexible placement and lower failure risk due to fewer components than centralized systems. However, many stand-alone devices can be integrated into centralized control systems later using additional hardware and professional setup. Smart controllers often support smart-home or IoT platforms out of the box, which can be a stepping stone toward a more comprehensive BAS or cloud-based management suite.

On the financial side, analyses of smart HVAC controller deployments in commercial buildings report that complete installations typically cost around $10,000 on average, with a range of about $5,000 to $15,000 depending on scope. The same sources note that savings from lower energy bills and extended equipment life can make these projects attractive for property owners. From a power and reliability perspective, those numbers are modest compared with the long-term cost of avoidable downtime, emergency repairs, and elevated demand charges.

Finally, build controls into your maintenance plan. Maintenance-focused research consistently recommends annual professional service, including system controls checks, supplemented by more frequent simple tasks such as filter inspection and ensuring vents are unobstructed. In more demanding climates or with older equipment, semi-annual or even quarterly checkups may be justified. Document any control changes, retrofits, or upgrades so that future testing, adjusting, and balancing efforts have accurate historical data to work from.

It depends on your building and goals. Basic Honeywell digital thermostats provide reliable on/off control at a set temperature but offer little in the way of scheduling, occupancy-based control, or analytics. Research on smart HVAC controllers indicates that advanced control, including remote monitoring, automated scheduling, and occupancy-based adjustments, can cut HVAC energy consumption and bills by roughly 10 to 40 percent when properly configured. If your building has variable occupancy, frequent setpoint overrides, or high energy costs, upgrading selected zones to smart or multi-zone thermostats can unlock significant gains.

Stand-alone controllers, including Honeywell-style thermostats, can manage climate effectively in smaller buildings or remote sites where centralized control is impractical. They offer user-friendly operation and lower complexity. For larger, multi-zone facilities with diverse uses, a DDC-based system integrated into a BAS brings important benefits: coordinated zoning, advanced scheduling, open-protocol integration, and analytics for energy and fault detection. A common strategy is to start with improved stand-alone controls in key areas and plan a phased path toward broader digital control as budgets and needs evolve.

Maintenance resources suggest that annual checks of system controls and thermostat calibration offer a good balance between cost and benefit in typical climates. This usually coincides with broader HVAC maintenance that includes coil cleaning, refrigerant checks, and duct inspections. In hot-humid, hot-dry, or otherwise extreme climates, semi-annual service may be justified because humidity, dust, and high runtime accelerate wear and fouling. Newer systems can often be maintained annually, while older and heavily used systems benefit from more frequent attention. In all cases, keep thermostat or BAS software up to date and address any recurring comfort or control issues promptly rather than allowing temporary workarounds to become permanent.

In the end, Honeywell controllers and thermostats are tools for shaping how energy moves through your building. When you pair the right controller types with sound installation, good balancing, and disciplined maintenance, you get stable comfort, lower HVAC power demand, and fewer surprises in both your mechanical rooms and your electrical panels. From a power system reliability standpoint, that is one of the highest-return investments you can make in your buildingŌĆÖs climate infrastructure.

Leave Your Comment