-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

A lot of industrial and commercial power systems are still running on General Electric PLC platforms that went in decades ago. In many plants I visit, those GE racks are quietly orchestrating UPS changeovers, inverter controls, generator sequencing, and switchgear interlocks. They have earned their reputation for toughness, but the surrounding world has changed: cybersecurity expectations, analytics, spareŌĆæpart availability, and the skill sets of your maintenance team are all very different from the 1980s and 1990s.

If your GE PLC is sitting at the center of a power protection system, a hard failure is no longer just an inconvenience. It can mean dark data centers, tripped switchgear, nuisance transfers on UPS systems, and significant safety exposure. The practical question is no longer whether to modernize, but how, and with what.

Drawing on migration work described by CIMTEC Automation with older GE PLCs, modernization strategies outlined by Balaji Switchgears, economic analyses from Schneider Electric, and real field projects such as Huffman EngineeringŌĆÖs major PLC renovation at a 125ŌĆæyearŌĆæold water plant, this article walks through realistic replacement paths for legacy GE PLCs. It also examines alternative control technologies, including modern PLC and ePAC platforms and open industrial controllers like Arduino OPTA, with a focus on reliability and power system continuity.

CIMTEC Automation has been involved with GE PLCs since the midŌĆæ1980s Series Six line, and notes that many of those legacy controllers are still running factory operations today. That longevity is impressive, but it hides several structural risks that now show up repeatedly across installed bases.

Modernization specialists such as Balaji Switchgears highlight that legacy PLCs suffer from reduced processing power, weak integration with contemporary networks, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and a shrinking supply of spare parts and experienced engineers. Those issues are not specific to GE, but older GE platforms are subject to the same forces. DO SupplyŌĆÖs work on legacy PLC systems adds more detail: obsolete PLCs rarely receive security updates, often depend on outdated operating systems, may no longer be supported by the original manufacturer, and can require scarce legacy skill sets to maintain. Spare parts become difficult or expensive to acquire, and repairs take longer.

WoodŌĆÖs guidance on control system obsolescence management reinforces the operational impact. As automation systems age, they bring increased downtime, rising maintenance costs, lack of integration with modern technologies, regulatory compliance difficulties, and serious cybersecurity threats. In power supply and protection systems, those risks translate directly into uptime, safety, and compliance exposure.

CIMTECŌĆÖs experience with GE platforms underscores a key lesson: planned migration from a functioning legacy PLC is generally less costly, less risky, and less stressful than reacting after a catastrophic failure when no dropŌĆæin replacement is available. In critical power systems backed by UPS and inverters, that distinction is even sharper, because emergency replacements often require rushed workarounds and temporary modes of operation that erode protection margins.

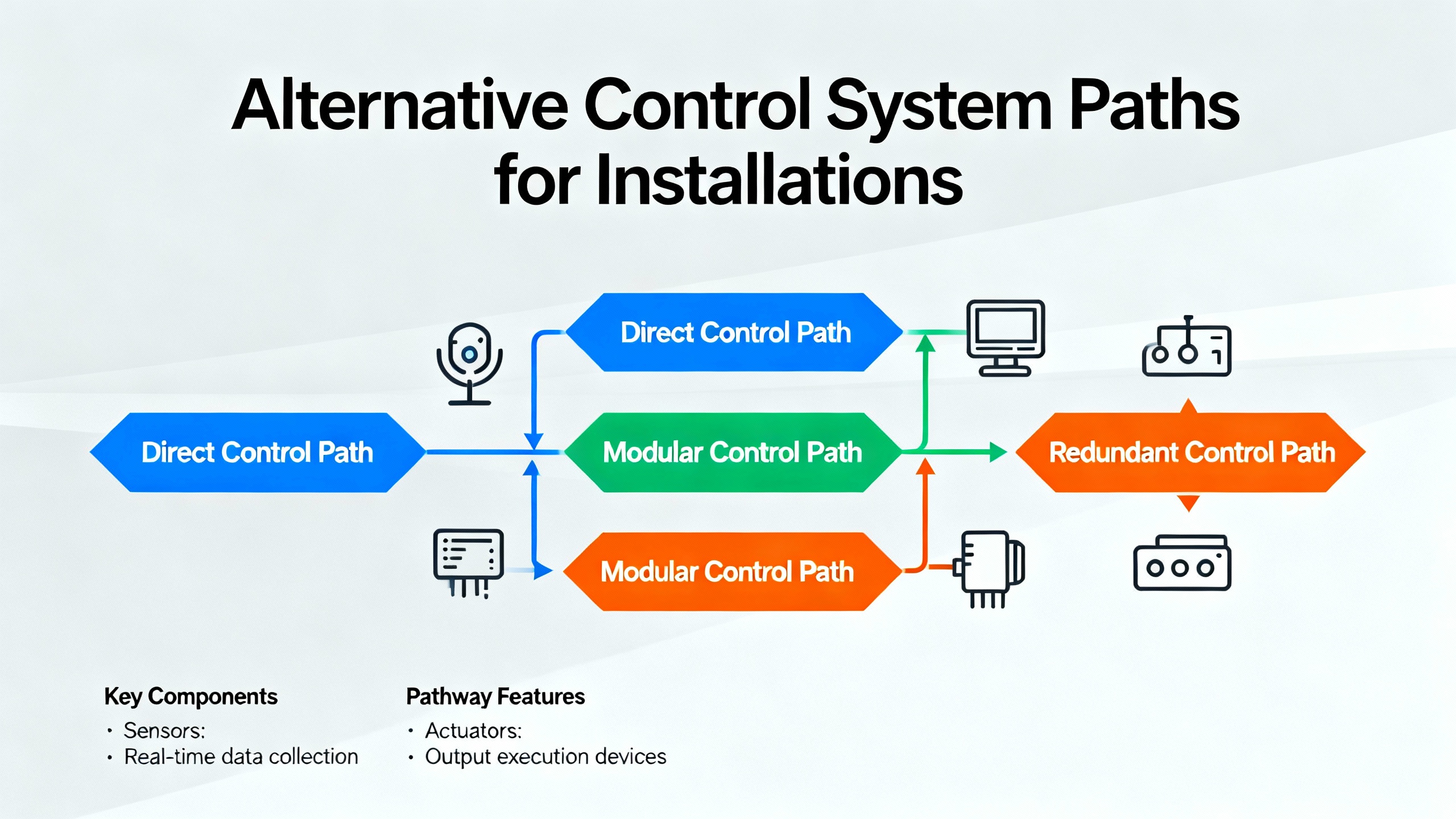

When you talk about ŌĆ£replacing a GE PLC,ŌĆØ you are not limited to a single vendor or architecture. In practice, facilities pursuing modernization tend to gravitate toward three broad paths: moving to a modern PLC or ePAC platform, migrating to an alternative PLC vendor, or, in carefully chosen cases, adopting industrial embedded controllers such as Arduino OPTA.

Balaji Switchgears describes modern PLC platforms as enablers for advanced diagnostics, data analytics, remote monitoring, and Industry 4.0 connectivity. Schneider Electric goes further by highlighting EthernetŌĆæenabled process automation controllers (ePACs) and realŌĆætime analytics as a basis for continuous accounting of asset performance. These controllers collect vibration, temperature, pressure, flow, and other variables, and feed them into cloudŌĆæbased historians that allow nearŌĆæunlimited storage of historical data and profitability profiles.

For power systems, that capability changes how a GE PLC replacement can be justified. Instead of viewing the project purely as ŌĆ£insuranceŌĆØ against a catastrophic failure, Schneider Electric recommends treating PLC modernization as a strategic profitability initiative. In a forest industry case, modernizing 45 PLC systems, including controllers and networks, eliminated failures that had been causing outages costing tens of thousands of dollars per hour. The project achieved seamless integration with an existing DCS, improved redundancy and online change capabilities, reduced downtime, and delivered a modernization return on investment of about 1.5 years.

In an industrial or commercial power context, similar ePACŌĆæstyle platforms can monitor breaker wear, transformer and UPS temperatures, inverter efficiency, and switchgear load profiles, while also orchestrating protection sequences. The key advantages compared with a legacy GE PLC are processing headroom, native Ethernet connectivity, cybersecurity features, and builtŌĆæin support for historians and analytics.

For GE PLC owners, one alternative is to migrate to a different major PLC brand entirely. Atlas OTŌĆÖs guide to replacing Rockwell SLC 500 PLCs illustrates the pattern: start with a thorough assessment of existing hardware, I/O configurations, and programming logic, then define future requirements such as expected I/O growth, communications, and integration with SCADA and higherŌĆælevel systems.

In that example, Rockwell recommends migrating to its CompactLogix platform, but Atlas OT explicitly notes that alternative PLC options, including IDEC, Opto 22, and Phoenix Contact PLCnext, may be more costŌĆæeffective depending on the application. Atlas also stresses that autoŌĆæconversion tools are not always the best option. In many cases, writing a new program for modern hardware and software is preferable because it allows adoption of current best practices and simplifies longŌĆæterm operation and maintenance.

Applied to a GE PLC environment, the pros of switching platforms include access to a broad ecosystem of integrators and training, strong longŌĆæterm vendor support, and robust connectivity to modern SCADA, DCS, and enterprise systems. The tradeoffs are the need to retrain staff, adapt maintenance practices, and perform more extensive logic and HMI conversion.

At the other end of the spectrum are industrial embedded platforms. Dojo Five describes replacing traditional PLCs with Arduino OPTA, an ŌĆ£Open Programmable and Transformative AutomationŌĆØ platform built on ArduinoŌĆÖs openŌĆæsource ecosystem but tailored for industrial use.

According to Dojo Five, Arduino OPTA brings several compelling traits. It is costŌĆæeffective compared with traditional PLCs, which is attractive to smaller facilities. Its modular design makes expansion straightforward, allowing systems to start small and scale with production needs. The familiar Arduino programming environment reduces the learning curve, and a large community contributes tutorials, libraries, and troubleshooting help. The platform is also wellŌĆæsuited for rapid prototyping, allowing engineering teams to test control strategies before broader deployment.

However, the same article points out significant challenges. Reliability in harsh industrial environments must be validated, particularly when comparing Arduino OPTA with established PLC families that have decades of field history. Integration can require extra engineering effort if existing systems depend on proprietary communication protocols or hardware. Longevity and product support must be carefully evaluated to avoid future compatibility issues and obsolescence.

For UPS, inverter, and power protection applications, those challenges are not academic. Embedded platforms like Arduino OPTA may make sense around the edges of a GE PLC replacement program, for example in secondary monitoring panels, engineering workstations, or nonŌĆæcritical subsystems. For core transfer, protection, and interlocking logic, the risk tolerance is usually much lower, and proven industrial PLC or ePAC platforms remain the preferred choice.

The GE Power Conversion portfolio, now part of GE Vernova, positions itself around integrated powerŌĆæelectronicsŌĆæbased systems: variableŌĆæspeed drives, gridŌĆætied converters and inverters, and associated transformers and switchgear. The portfolio emphasizes digital control platforms that coordinate drives, converters, and rotating machines, along with remote monitoring, diagnostics, and performance optimization over the lifecycle.

While the available material focuses more on drive and converter control than on standŌĆæalone PLC products, it illustrates another alternative for operators of GE power systems. Instead of thinking in terms of isolated PLCs, modernization can be framed as adopting integrated powerŌĆæconversion systems with builtŌĆæin digital control, analytics, and lifecycle services. For facilities already deeply invested in GEŌĆÖs power equipment, aligning control modernization with that ecosystem can simplify integration and lifecycle support, provided the chosen platform meets your requirements for openness and multiŌĆævendor interoperability.

Once you have a sense of the replacement technology, you still face a strategic question: how to execute the migration with acceptable risk. Here, Balaji SwitchgearsŌĆÖ modernization framework is a useful starting point, with direct replacement, phased migration, comprehensive overhaul, and hybrid solutions as the main archetypes.

Direct replacement means swapping old PLC hardware for new models while retaining the existing program architecture. Balaji Switchgears describes this as a costŌĆæeffective approach for smaller or simpler systems when downtime windows are limited and the current control philosophy is sound.

For GE PLCs, CIMTECŌĆÖs process shows what direct replacement looks like in practice. Customers provide the current program from the old GE PLC, and a product specialist reviews it to propose a migration. The first major phase is hardware evaluation: deciding which modules can remain, which need new firmware or chips, and which must be fully replaced. Program evaluation then examines the existing logic in detail, including the number of rungs, instructions that will not convert cleanly, the quality of rung comments, differences between current tag naming rules and those of modern software, and I/O map complexity. The evaluation also identifies code sections that can be simplified or removed.

Program conversion typically combines automated tools with a thorough proofread of the converted code. CIMTEC notes that this review can take from roughly three hours to three weeks, depending on program length and complexity. After that, engineers perform manual edits to resolve conversion gaps and optimization opportunities. Finally, the team acquires the new hardware, tests the converted program on it, and installs the package at the facility.

The advantage for GE PLC owners is lower disruption and predictable cost. The downside is that you may not fully exploit the advanced diagnostics, analytics, and connectivity features of modern controllers because the underlying control strategy remains rooted in older design assumptions.

Phased migration replaces parts of the system over time, allowing the plant to continue running. Balaji Switchgears recommends this approach for large or continuous operations that cannot tolerate long shutdowns.

Huffman EngineeringŌĆÖs renovation of the 125ŌĆæyearŌĆæold Florence Water Treatment Plant, operated by Metropolitan Utilities District in Omaha, is a clear demonstration of how phased migration works in a critical infrastructure setting. The plant can supply 158 million gallons per day, about half of the utilityŌĆÖs total capacity, so a full shutdown was not acceptable. Over an eightŌĆæweek preŌĆæshutdown period, Huffman Engineering replaced six PLC panels and updated three more to the new districtŌĆæwide SCADA and PLC standard while the plant ran in manual control. During a planned threeŌĆæweek filtration shutdown, they replaced five additional PLC panels.

Several practices from that project are directly applicable to GE PLC replacements in power systems. All field wiring was verified and labeled before removing old panels, addressing the common brownfield problem of poor documentation. PLC panel sequencing was coordinated with the installation of a new fiberŌĆæoptic ring designed for bidirectional communications, eliminating singleŌĆædevice failures as a cause of total communications loss. HMI software for the filter plant was developed so it could operate independently of central SCADA, providing a local backup control path. PreŌĆæinstallation HMI checkout simulated every PLC and verified each point inŌĆæhouse before field deployment. During cutovers, dual server communications and temporary control panels kept critical valves operating.

For UPS and switchgear systems, an analogous phased plan might upgrade one lineup, one transfer scheme, or one substation at a time, using temporary control panels and manual modes to hold risk at acceptable levels.

A comprehensive overhaul replaces the entire PLC infrastructure in one coordinated program. Balaji Switchgears notes that this approach demands major investment and planning, but delivers maximum benefits in scalability, performance, and longŌĆæterm future readiness.

Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs forest industry case shows the payoff when a plant commits to such a program. Modernizing 45 aging PLC systems, including controllers, networks, and services, eliminated the failures that had previously caused highŌĆæcost production outages. The project improved redundancy and online change capabilities, integrated seamlessly with an existing DCS, reduced downtime, and generated an approximate 1.5ŌĆæyear ROI. Schneider Electric recommends using installedŌĆæbase assessments, realŌĆætime accounting, and analytics to frame such modernization projects as profit and revenue enablers rather than purely as lifecycle replacements.

For a GE PLC estate that underpins highŌĆævalue power assets, a full overhaul becomes attractive when the installed base is uniformly obsolete, when cybersecurity and compliance gaps are serious, or when you want to standardize on a modern platform across multiple sites. The added engineering effort creates an opportunity to rethink control strategies, adopt standardized naming conventions, rationalize alarms, and design architectures explicitly for analytics and remote support.

Hybrid solutions mix old and new PLC components, allowing gradual modernization while spreading costs and reducing disruption. Balaji Switchgears presents this as a viable approach when budgets are constrained or when parts of the legacy system still have adequate lifecycle and performance.

Hybrid architectures might involve keeping some GE I/O racks while replacing the CPU with a modern controller through a migration adapter, or leaving certain subsystems on the legacy GE PLC and interfacing them over a network to a new supervisory controller. QualitrolŌĆÖs generic guidance on PLC migrations emphasizes that, in any such design, the interfaces between new and old components must be carefully analyzed and tested, with clear rollback plans in case problems emerge during commissioning.

The risk with hybrid approaches is that they can entrench complexity. Maintenance teams must support both legacy GE technology and new controllers, and cybersecurity weaknesses in the old components can undermine the overall system. Hybrid architectures are best viewed as a transitional state on the way to a fully modernized control environment.

Many guidance documents converge on a structured migration process. Balaji Switchgears emphasizes assessment, objective setting, hardware and software selection, planning, testing, and training. QualitrolŌĆÖs work on PLC migrations adds installedŌĆæbase assessment, risk analysis, and lifecycle planning. CIMTEC and Huffman Engineering provide real project detail on code conversion, hardware testing, and staged cutovers.

A practical workflow for GE PLC replacement in power systems usually begins with inventory and risk assessment. All GE PLCs should be cataloged, including models, firmware, I/O counts, networks, and attached equipment. Failure history, known obsolescence status, and spareŌĆæpart availability are recorded. RL Consulting notes that this is also the time to map standards and compliance requirements, referencing frameworks such as IEC 61131ŌĆæ3 for programming, NFPA 79 for electrical safety of industrial machinery, IEC 62443 for industrial cybersecurity, and UL 508A for control panel design.

The next stage is detailed program and hardware evaluation, similar to CIMTECŌĆÖs approach. Engineers analyze the GE logic, counting rungs and instructions that will not convert directly, checking rung comments and address schemes, reviewing the I/O map, and identifying opportunities to simplify logic or remove obsolete code. Hardware evaluation determines which racks, modules, and field devices can be retained, what requires firmware updates, and what must be replaced outright.

Code conversion and lab testing follow. Automated conversion tools are helpful, but both CIMTEC and Atlas OT emphasize the need for thorough manual proofreading and edits to resolve logic issues and optimize the code for the new platform. Huffman EngineeringŌĆÖs preŌĆæinstallation HMI checkout shows the value of simulating PLC communications and validating every point in a controlled environment before going live. For power systems, bench testing should also include simulation of typical and abnormal power events to validate trip, transfer, and alarm sequences.

Cutover planning and execution are then developed around production constraints and risk tolerance. HuffmanŌĆÖs Florence project demonstrates the value of combining preŌĆæshutdown work (such as panel replacement under manual control) with carefully planned outages for highŌĆærisk changes. Risk mitigation measures include dual server communications, temporary control panels, and, for power systems, ensuring clean and stable power to new controllers during cutover. Industrial Automation Co. stresses the importance of protecting PLCs and associated electronics from voltage fluctuations using surge protectors and uninterruptible power supplies, which is especially critical when control power sources may be reconfigured.

The final step is training, documentation, and organizational adoption. RL Consulting points out that customers value clear, upŌĆætoŌĆædate documentation, intuitive HMIs and alarm systems, and training that enables inŌĆæhouse staff to handle firstŌĆæline troubleshooting. GEŌĆÖs own Change Acceleration Process (CAP) adds a useful lens. CAP frames change effectiveness as the product of the quality of the technical strategy and the acceptance of that strategy among people. Analyses of hundreds of projects showed that excellent technical plans often failed because of insufficient attention to cultural and people factors. CAP outlines steps such as leading change, creating a shared need, shaping a vision in terms of observable behaviors, mobilizing commitment, making change last, monitoring progress, and changing systems and structures to reinforce the new state. Applying that discipline to GE PLC replacement helps ensure that operators and technicians embrace the new platform rather than treating it as a temporary ŌĆ£flavor of the month.ŌĆØ

Because the focus here is on UPS, inverters, and power protection, it is not enough to swap a GE PLC for a newer controller. You must ensure that the new control system is designed and maintained with power reliability in mind.

PLC maintenance guides from UpKeep, eWorkOrders, Industrial Automation Co., PDF Supply, and PLC Department repeatedly emphasize environmental control, cleaning, and electrical quality. They recommend keeping PLCs within specified temperature and humidity ranges, using enclosures and filters to prevent dust and debris from entering, auditing wiring for electromagnetic and radioŌĆæfrequency interference, and maintaining clean ventilation and filters. They also highlight the importance of checking LED indicators, inspecting sensors, monitoring battery status, and maintaining spareŌĆæparts inventories.

Industrial Automation Co. specifically recommends using surge protectors and UPS units to protect PLCs against voltage fluctuations. In a powerŌĆæsystem upgrade, that means verifying that control power for the new PLC, communications gear, and HMIs is fed from a suitably sized UPS or other conditioned source, and that the UPS itself is integrated into the monitoring and maintenance regime.

Allied Reliability distinguishes preventive maintenance, which relies on time and usage data such as mean time to failure, from predictive maintenance, which uses condition monitoring tools and sensors to determine when equipment actually needs intervention. Modern PLCs and ePACs with analog inputs and analytics support that predictive approach, capturing temperature, vibration, and other signals that can be used to detect emerging issues in breakers, transformers, UPS modules, and switchgear. When you replace a GE PLC, you have an opportunity to design those condition monitoring pathways into the control system so that power reliability is continuously managed rather than addressed only after failures.

A common misconception is that PLC age alone determines when replacement is due. DO Supply cautions that a legacy PLC system does not have to be old to be problematic. Instead, they define a legacy system as one whose underlying technology is outdated or no longer supported, and which slows operations, prevents seamless integration of new features, or hinders business expansion.

Signs that a PLC is becoming a liability include frequent failures that compromise core operations, serial communication networks that are too slow for current data needs, lack of room for I/O expansion, aftermarket parts that are expensive or hard to find, and the original manufacturer discontinuing technical support. WoodŌĆÖs overview of obsolescence risks adds lack of integration with modern technologies, regulatory compliance issues, and cybersecurity threats to this list.

Schneider Electric recommends connecting modernization decisions to business value through realŌĆætime accounting. By tracking production value, energy costs, and raw material costs ŌĆō or, in a power context, energy efficiency, fuel use for generators, and the cost of unplanned transfers ŌĆō and by benchmarking similar assets, operators can calculate each assetŌĆÖs contribution to the bottom line. That profitability index can then be used to prioritize which GE PLCs to replace first and to justify investment in modern control platforms.

For most facilities, the prudent point to start planning is when spareŌĆæpart availability becomes uncertain, firmware and programming tools are clearly outdated, or cybersecurity requirements cannot be met with the existing platform. At that point, an installedŌĆæbase assessment and migration roadmap are inexpensive compared with the potential cost of a major power interruption caused by an unplanned failure.

The main replacement approaches can be compared in terms of fit, strengths, and constraints, drawing on the modernization and migration experiences described by Balaji Switchgears, Schneider Electric, CIMTEC Automation, Atlas OT, Dojo Five, and others.

| Replacement approach | Where it fits | Strengths | WatchŌĆæouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct likeŌĆæforŌĆælike replacement on a modern PLC platform | Smaller or wellŌĆæunderstood GE applications where existing logic is sound and extended downtime is not acceptable | Lower project risk and cost, minimal change to operator experience, shorter engineering time; can reuse much of the existing I/O and wiring as demonstrated by CIMTECŌĆÖs GE migrations | May not fully exploit advanced diagnostics, analytics, or cybersecurity features; risks carrying forward suboptimal control strategies and documentation gaps |

| Phased migration using modern PLCs or ePACs | Large or continuous processes where full shutdown is impractical; complex power systems where only limited outages are possible | Allows production to continue; spreads cost over time; enables learning from early phases; Huffman EngineeringŌĆÖs water plant project shows this can be done without full plant shutdown while adding fiber rings, local HMIs, and historians | Requires rigorous planning and coordination; temporary hybrid states can be complex; prolonged coexistence of old and new systems increases the importance of clear interfaces and cybersecurity |

| Comprehensive overhaul using modern PLC or ePAC architecture | Sites with uniformly obsolete GE PLCs, substantial cybersecurity or compliance gaps, or strong business drivers for analytics and optimization | Provides maximum future readiness, standardization, and integration; Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs forest industry modernization achieved elimination of chronic failures and an ROI of about 1.5 years while improving redundancy and online change capabilities | High upfront investment, more extensive engineering and testing; demands strong change management and training so staff can adopt new tools and workflows |

| Migration to alternative PLC vendors | Facilities wanting to standardize on a nonŌĆæGE platform, or seeking specific capabilities and ecosystem support from other vendors such as those discussed by Atlas OT | Access to wider ecosystems, tools, and training; can leverage vendor migration tools and services; offers flexibility to select the bestŌĆæfit platform across multiple sites | Requires staff retraining and adaptation of maintenance practices; may involve more intensive logic and HMI conversion; vendor choices can lock in future platform direction |

| Industrial embedded platforms such as Arduino OPTA | NonŌĆæcritical subsystems, pilot projects, rapid prototyping, or costŌĆæsensitive applications where openŌĆæsource flexibility is advantageous | Lower hardware cost, modular scalability, strong community support, fast prototyping cycles, and flexible customization as highlighted by Dojo Five | Reliability, integration, and longevity must be validated for the specific environment; not all applications, especially safetyŌĆæcritical power protection, are appropriate for such platforms; longŌĆæterm support and cybersecurity need careful evaluation |

| Hybrid architectures combining GE PLCs and new controllers | Transitional states where budgets or outage windows limit full replacement, or where selected subsystems must be modernized first | Enables gradual modernization while preserving working GE hardware; can be tuned to tackle highestŌĆærisk or most obsolete components early | Increases complexity, with dual technologies and potential cybersecurity weaknesses in legacy components; requires careful interface design and testing; should be viewed as temporary rather than permanent |

CIMTEC Automation notes that many plants using older GE PLCs are primarily concerned about the difficulty of finding a replacement if a controller fails unexpectedly. Their experience, and the broader guidance from modernization specialists, is that proactive migration from a functioning legacy PLC is generally less costly, less risky, and less stressful than reacting after a failure. In critical power systems, where a PLC failure can translate directly into costly downtime and safety exposure, waiting until failure is a highŌĆærisk strategy.

Dojo Five presents Arduino OPTA as a costŌĆæeffective, modular, open platform that can replace traditional PLCs in some industrial automation applications. They also emphasize challenges around reliability in industrial environments, integration with proprietary protocols, and longŌĆæterm support. For core UPS transfer logic, switchgear interlocking, and protection functions, the tolerance for failure is extremely low, and most operators will favor proven PLC or ePAC platforms that have established field history and robust vendor support. Arduino OPTA and similar platforms are better suited to peripheral functions, rapid prototyping, or nonŌĆæcritical subsystems, unless and until they are validated and certified for the specific powerŌĆæsystem use case.

GEŌĆÖs Change Acceleration Process suggests that many technically sound projects underperform because of low acceptance among the people who must live with the new system. In PLC replacement, the biggest nonŌĆætechnical risk is often insufficient engagement of operators, technicians, and engineers. If the migration is seen as an imposed change rather than a response to a shared need, staff may resist new tools, bypass new features, or delay necessary training. Applying CAP principles ŌĆō sustained leadership commitment, a clear shared need, an understandable vision of the future state, and deliberate efforts to make change last ŌĆō greatly increases the likelihood that a technically successful GE PLC replacement will deliver its promised reliability and profitability benefits.

Modernizing away from legacy GE PLCs is not simply a matter of swapping controllers. It is a strategic opportunity to harden the reliability of your UPS and power protection systems, to embed predictive maintenance and analytics, and to align your control architecture with current cybersecurity and regulatory expectations. When you treat the project with that level of seriousness ŌĆō balancing technology, people, and profitability ŌĆō the replacement of a GE PLC becomes a practical step toward a more resilient and futureŌĆæready power infrastructure.

Leave Your Comment