-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When a Distributed Control System (DCS) or UPS chain fails in a plant, data center, or hospital, the question that matters is brutally simple: how fast can you get the right part on site, installed, and proven? In my experience with industrial and commercial power systems, the gap between a brief disturbance and a prolonged, reputation-damaging outage often comes down to whether a single controller, I/O card, or UPS module can be sourced and delivered in hours rather than days.

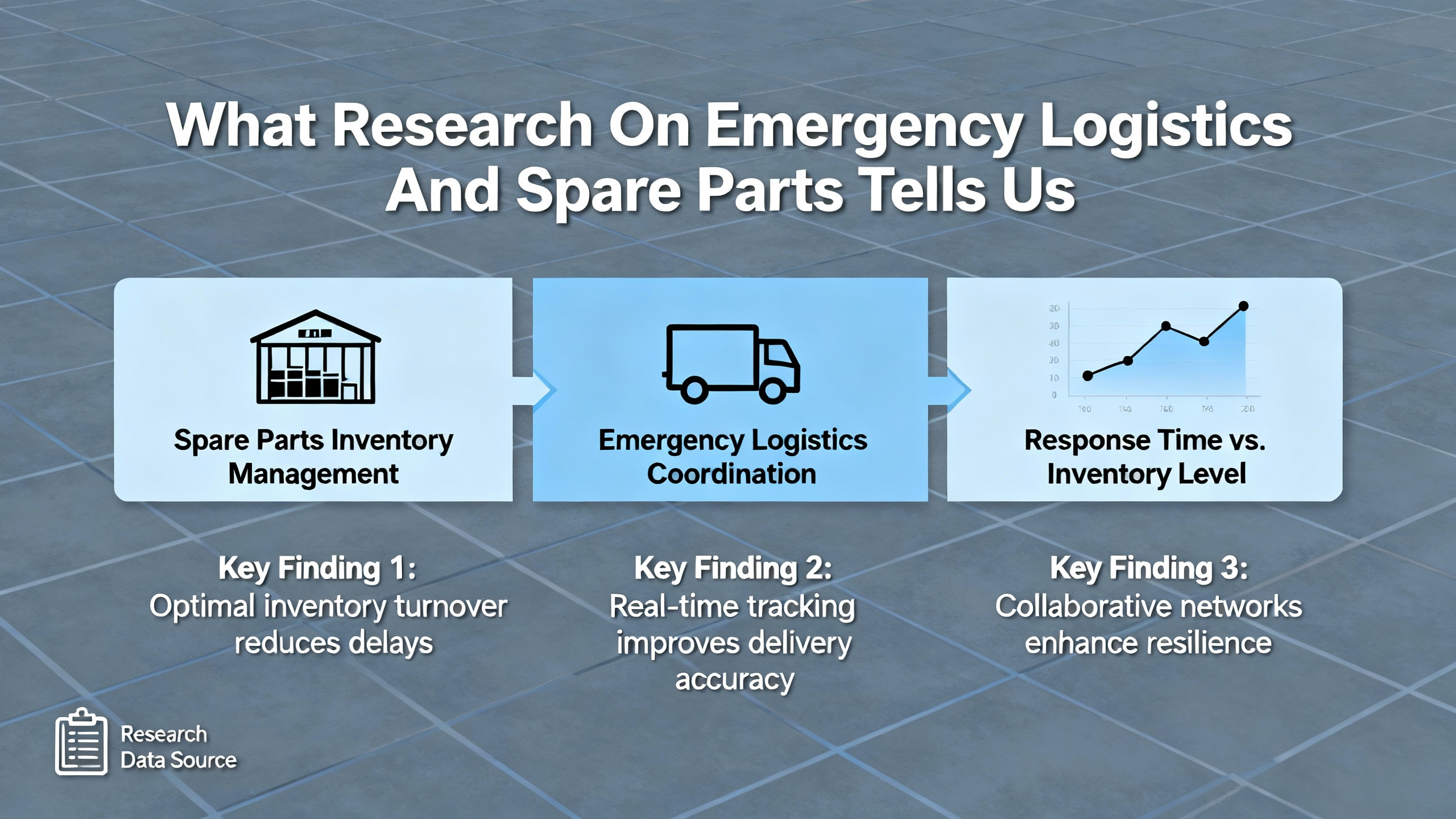

The challenge is that DCS, UPS, and inverter spare parts live at the intersection of two worlds. On one side, you have tightly engineered, safetyŌĆæcritical assets that cannot tolerate improvisation. On the other, you have supply chains that have been driven for years toward lean inventory and justŌĆæinŌĆætime delivery. Research summarized in industry sources such as Inbound Logistics and ScienceDirect shows how highly optimized, lowŌĆæredundancy supply chains become fragile under stress, particularly when disasters create both supply disruptions and demand surges at the same time. For emergency DCS parts, that fragility translates directly into downtime risk.

This article brings together lessons from spare parts optimization, emergency logistics, and disaster supply chain research, then applies them to emergency DCS and powerŌĆæprotection parts delivery. The goal is practical: help you design a parts and logistics strategy that can withstand critical failures in your automation and power chain without sacrificing cost control the rest of the year.

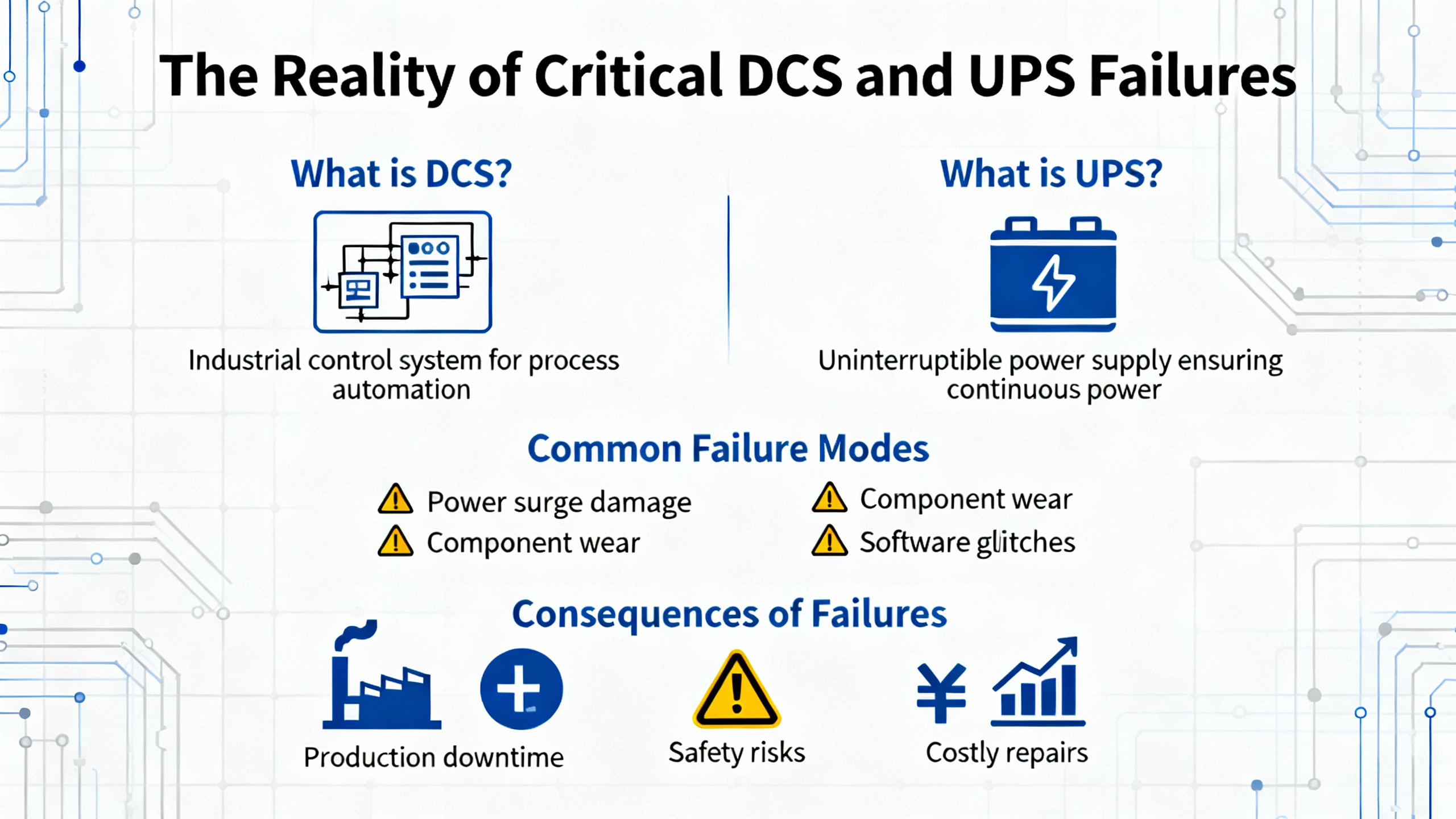

A modern industrial DCS is the nervous system of the plant. It ties together process measurements, control logic, safety interlocks, historian data, and operator interfaces. In commercial facilities, building automation, fire systems, and power management often ride on similar control infrastructure. All of it depends on a clean, continuous power path through UPS systems, inverters, switchgear, and distribution panels.

Even with redundancy, common single points of failure still show up in incident reviews. Typical examples include failed DCS power supplies, controller or I/O modules that are not in truly redundant configurations, obsolete communication cards, UPS power modules, or battery strings that have not been replaced on time. When these fail without a compatible spare on site, recovery time is dictated not by your technicians, but by your supply chain.

Several bodies of work on disasters and supply chain performance, including analyses published by FEMA and NCBI, underscore that recovery success is less about the volume of supplies and more about how quickly normal supply chains can resume after a disruption. During Hurricane Maria, for example, research summarized in an NCBI book chapter describes how large relief shipments into San Juan clogged the primary port because local trucking capacity was insufficient to move goods inland. The lesson is highly relevant to DCS parts: having the part somewhere in the world does not help if your logistics channels cannot deliver it to the failed system in time.

Critical automation and powerŌĆæprotection failures are also extremely timeŌĆæsensitive demands. Work in ScienceDirect on supply chain resilience in disruptions and demand surges emphasizes that resilience should be measured partly by how much timeŌĆæsensitive demand you fulfill during and after a disruption, not just whether you eventually fill all orders. For a DCS or UPS outage, the time window is measured in minutes and hours, not weeks. That is why emergency DCS parts delivery must be treated as a specific, engineered capability, not just a side effect of general procurement.

Although most published research focuses on healthcare, food, and consumer goods rather than power systems, the principles transfer cleanly.

Guidance from FEMAŌĆÖs Supply Chain Resilience Guide makes two key points that matter for DCS spares. First, most critical goods in a disaster still flow through private, commercial supply chains rather than government stockpiles. Second, government and emergency managers are most effective when they support and unblock those existing supply chains, instead of trying to run parallel systems. For an industrial operator, that translates into designing your DCS parts strategy so it works with your OEMs, distributors, and logistics partners instead of trying to build an isolated, bespoke channel that no one else uses.

A NCBI chapter on relief supply chains during the 2017 hurricane season shows how preŌĆædisaster surges in buying and ad hoc government ordering can pull limited logistics capacity away from commercial resupply. That same competition for trucks, drivers, and warehouse space can hit you when you most need a specific PLC rack or UPS module rushed across the country. The chapter argues that recovery should be measured by how quickly local supply chains bounce back, such as how fast stores and gas stations reopen. In a DCS context, your equivalent metric is how quickly you can restore normal control and power functionality using your standard, wellŌĆærehearsed spare parts channels.

On the spare parts side, a synthesis of industry work from providers like Sophus highlights how structured spare parts optimization can both cut cost and improve availability. One analysis notes that integrating order processing with an inventory system can boost productivity by up to 25 percent, cut space usage by roughly 20 percent, and increase stock utilization efficiency by around 30 percent, when done correctly. Forecasting models that incorporate historical demand and product life cycles are reported to lower inventory levels by about 30 percent while improving fill rates by around 10 percent. Those are not DCSŌĆæspecific numbers, but they do show that ŌĆ£more spares everywhereŌĆØ is not the only way to get reliability; targeted, dataŌĆædriven stocking can improve service while freeing cash and space.

Emergency logistics guidance from industry sources such as analyses of emergency logistics and pallet strategies adds another layer. Effective emergency logistics is characterized by speed, flexibility, efficiency, coordination, and resilience. The recommended strategies are repeatable: preŌĆæposition supplies in strategic locations, build flexible transportation networks with multiple modes, and use realŌĆætime tracking and analytics. The cargo might be relief food or spare DCS power supplies; the logistics principles are the same.

Finally, global health supply chain preparedness work from groups such as GHSCŌĆæPSM recommends clearly defined emergency commodity lists, preŌĆænegotiated vendor agreements, and written emergency supply chain plans with explicit triggers for activation and deactivation. If a national program treating outbreaks can benefit from defined emergency kits and delegated authorities, so can an industrial operation that wants to move faster than standard purchasing when a critical controller fails.

To make emergency DCS parts delivery real, you need to address three design questions: which parts you hold, where you hold them, and how you trigger their movement.

The starting point is not the catalog, but the process. You need a clear picture of which loads and control functions are truly critical. For a manufacturing plant, that might be furnace controls, safety instrumented functions, and the UPS chain that feeds them. For a hospital, it will include clinical systems, emergency lighting, and lifeŌĆæsafety controls. For a data center, focus lands on power distribution, UPS/inverter systems, cooling controls, and the layers of network and management systems that allow remote operation.

Once you have that criticality map, you can identify the specific DCS, PLC, and powerŌĆæprotection components whose failure could put those functions at risk. Typical categories include system power supplies, communication processors, I/O cards tied to protection and trip signals, HMI servers, UPS rectifier or inverter modules, static transfer switches, key switchboard control relays, and specialized interface modules. The point is not to stock every possible spare, but to understand which devices have the greatest consequence of failure combined with realistic failure modes.

Research on spare parts optimization summarized by Sophus suggests using Pareto analysis to identify the relatively small subset of parts that drive most usage and risk, with one study noting that focusing on roughly 20 percent of parts can address approximately 80 percent of inventory issues. For DCS and UPS systems, that usually maps to a short list of modules that appear repeatedly across panels and cabinets.

After you know what is critical, you still need to decide how many of each item to hold. This is where data and structured methods matter more than rules of thumb.

Sophus and other inventory optimization sources emphasize combining historical demand, seasonality, product life cycles, and sales or consumption data to build forecasts. While critical failures are rare by design, you can still use data from nuisance failures, passedŌĆæusefulŌĆælife replacements, and multiŌĆæsite fleets to estimate demand for common modules.

Classic tools such as economic order quantity and safety stock calculations, when paired with structured replenishment planning, are reported to resolve a large share of inventory problems in generic spare parts environments. Industry summaries suggest that wellŌĆæintegrated replenishment planning can address up to 80 percent of inventoryŌĆærelated issues. For DCS parts, that means quantifying how many controller failures, UPS module swaps, or network card replacements you expect over a given time horizon, then explicitly deciding how much of that you will cover through stocked spares versus expedited procurement.

You also need to recognize that inventory has a cost of capital, storage, and obsolescence. Supply chain articles on warehouse and distribution center inventory management often cite inventory carrying costs that can reach 20 to 30 percent of inventory value annually. That is a strong argument for focusing emergency stock on items where downtime cost substantially exceeds carrying cost.

The next question is location. Research from Sophus and FEMA both highlight the advantages of centralized inventory with wellŌĆædesigned distribution networks, but there is no single right answer.

For the fastest possible response, local site inventory is unmatched. If your risk analysis shows that a controller or UPS module failure will immediately stop a critical process, and the business impact per hour is large, siteŌĆæheld inventory is usually justified. The carrying cost for a small number of these highŌĆæconsequence parts is trivial compared with even a single outage event.

A regional hub model, often operated by your organization or a logistics partner, can work well for moderately critical parts and multiŌĆæsite fleets. Sophus notes that a centralized inventory management system across locations paired with an optimized network designŌĆöusing hubŌĆæandŌĆæspoke flows and coordination between distribution centersŌĆöimproves visibility and control while reducing total inventory. For DCS spares, that could mean a central hub holding certain power supplies and standardized I/O cards that multiple plants use, backed by fast shipping.

Finally, you may decide to rely on OEM or distributor inventory for lowŌĆæcriticality or lowŌĆæusage items, provided you have realistic leadŌĆætime commitments. Here, research summarized by Inbound Logistics on supply chain resilience is a caution: a survey of global shippers cited by the Business Continuity Institute found that 64 percent either did not know whether key suppliers would prioritize them during disruption or only knew for some suppliers. For emergency DCS parts, you do not want to be in that 64 percent. If you choose not to hold a part yourself, you need explicit, written commitments on emergency ordering, shipping, and prioritization.

Having the right parts in the right place is only half the story. You also need a delivery chain engineered for speed and reliability when conditions are far from normal.

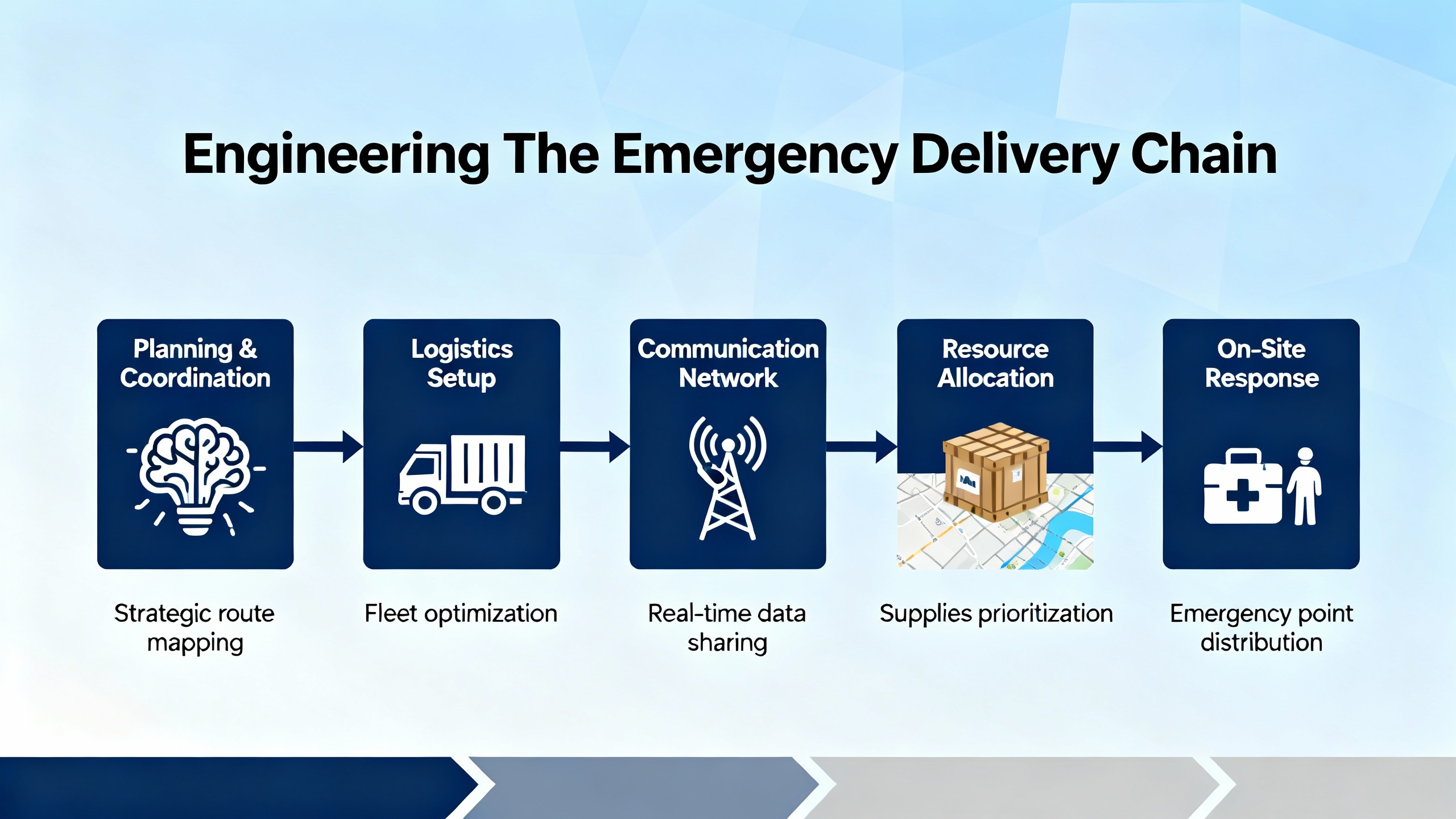

Emergency logistics research summarized in industry analyses of disaster response suggests three reinforcing strategies: preŌĆæpositioning, flexible transportation networks, and technologyŌĆædriven tracking.

PreŌĆæpositioning is simply the deliberate placement of critical inventory closer to where it will be used. For DCS spares, this might mean stocking at a regional depot near clusters of plants or data centers, or arranging for your OEM to hold contractually reserved stock in a warehouse within a target travel radius.

Flexible transportation means building options. Sophus and other supply chain optimization work recommend a mix of air, road, and maritime transport to balance cost, speed, and coverage. In an emergency DCS parts context, that often translates into an air express option for highŌĆævalue modules when every hour of downtime is expensive, backed by road transport for less urgent replenishment and redistribution.

Technology completes the picture. Emergency logistics articles highlight the value of realŌĆætime tracking and predictive analytics. For DCS spares, that can mean shipment tracking tied into your incident management system so that operations knows exactly when a replacement UPS module will arrive, or analytics that suggest alternative shipping routes if weather or infrastructure issues threaten your standard lanes.

A surprising amount of emergency response time is lost inside warehouses and distribution centers. Research from Baxter Planning, Solus, and others on distribution center layout and inventory management shows that optimized layouts can reduce internal transportation costs, lower safety stock, and improve inventory visibility.

Several practices are particularly relevant for DCS spare parts hubs. Organizing storage zones based on demandŌĆökeeping fastŌĆæmoving and critical modules closest to packing and shippingŌĆöreduces pick time. Ensuring accurate, realŌĆætime inventory with barcode or RFID scanning and robust warehouse management systems avoids the painful situation where the system shows a spare DCS power supply that cannot actually be located. Dynamic slotting, where locations are adjusted based on changing velocity and seasonality, helps maintain performance as your installed base evolves.

Cycle counting strategies described by warehouse optimization providers, where partial inventory is counted continuously without shutting down operations, can keep accuracy high without disruptive full physical counts. For emergency DCS parts, treating your critical class of spares as the highest priority for frequent cycle counts is a straightforward way to reduce unpleasant surprises during a failure.

Emergency logistics research on pallet materials might seem far removed from DCS modules, but the underlying idea is relevant: your shipping platform has to survive rough handling in bad conditions. Analyses that compare plastic pallets to wood pallets in disaster zones emphasize durability, hygiene, and uniformity under stress. In a DCS context, the priority is protecting sensitive electronics from shock, electrostatic discharge, and moisture during accelerated shipping.

That means specifying appropriate packaging standards in your contracts: antistatic bags, cushioning that can tolerate vibration, and robust outer cartons or cases that can withstand being moved quickly through multiple hubs. It also means ensuring that your emergency logistics partners understand that these are not commodity goods; clear labeling and handling instructions reduce the risk of damage while rushing parts to a site.

Technical spares and logistics design will not deliver under stress if governance and information flow are weak. Disaster supply chain work from FEMA, GHSCŌĆæPSM, and NCBI all point to the same conclusion: relationships, roles, and communication protocols must be defined before the crisis.

GHSCŌĆæPSMŌĆÖs best practices for public health emergency supply chains call for written emergency supply chain plans that define triggers for activation and deactivation, command structures, communication flows, and the transition back to routine operations. For emergency DCS parts, you need something similar, scaled to your organization.

That includes a clear definition of who can declare a critical part emergency, what criteria they must check (for example, failed redundancy, impact on safety or critical loads, expected downtime cost), who is authorized to bypass normal purchasing workflows, and which logistics partners and OEM contacts are engaged by default. PreŌĆænegotiated framework agreements with suppliers that include emergency leadŌĆætime and allocation commitments reduce the need for frantic, ad hoc negotiations during a fault.

ComplianceŌĆæfocused case studies from material handling projects show the value of having dedicated roles to manage licensing, permitting, and contractor credentials so projects stay on time. While emergency DCS parts shipping does not usually implicate building permits, there is an analogy: designating a specific role or team to own supplier qualification, contract maintenance, and documentation for emergency spares avoids confusion over responsibilities.

PagerDutyŌĆÖs discussion of supply chain resilience strategies frames resilience as the ability to anticipate, respond to, and recover from disruption while maintaining the flow of goods and services. A central theme is visibility and automation: integrating observability signals, turning them into actionable alerts, and automating workflows that reroute work and escalate incidents.

For DCS parts, that means connecting your asset management, inventory, and incident management systems. When a UPS module or DCS controller fails, the ideal state is that your incident system automatically pulls the asset record, checks spare availability, suggests the nearest location with the right part, and triggers a preŌĆædefined logistics workflow if local stock is insufficient.

Automation can also support drills and risk mitigation. PagerDutyŌĆÖs examples include regular failover simulations in data centers and preŌĆædefined workflows for highŌĆærisk events. In a DCS context, you can schedule test incidents where a critical module is ŌĆ£failedŌĆØ on paper and your team walks through the steps of sourcing, shipping, and installing a spare, measuring the time taken and points of friction.

When a real failure occurs, your response should follow a repeatable, wellŌĆæunderstood pattern rather than improvisation.

The technical teamŌĆÖs first priority is always to stabilize the situation: ensuring personnel safety, isolating faulty equipment, and placing the process in the safest available state. As that stabilizing work happens, the DCS or power engineer responsible should quickly characterize the failure at the part level, identifying the exact module and revision required. In many incidents, the dominant delay is not shipping but simply confirming the correct part.

Once the part is identified, the emergency spares playbook should initiate. The responsible engineer or duty manager confirms whether an onŌĆæsite spare is available, in good condition, and within its storage life. If so, attention shifts to installation, testing, and root cause analysis.

If no onŌĆæsite spare exists, or if more than one is required, the logistics side takes over according to the preŌĆædefined plan. The system checks regional hubs and OEM or distributor stock, selects the source that can meet the target recovery time objective, and triggers the appropriate shipping mode. Research from Purolator International on disasterŌĆæready supply chains stresses the importance of having alternate suppliers and transport options preŌĆædefined, along with contingency plans that include backup ways to move goods and an emergency fund.

Throughout the event, communication matters. FEMA and NCBI both highlight the value of shared situational awareness in disaster logistics; the same holds for a plantŌĆælevel failure. Operations, maintenance, management, and external partners should have a common picture of part status, shipping milestones, and realistic restoration times. That shared picture supports informed decisions about load shedding, production rescheduling, and customer communication.

Finally, when the event is over, resist the temptation to treat it as a oneŌĆæoff. GHSCŌĆæPSM and FEMA emphasize afterŌĆæaction reviews and iterative improvement. For DCS emergency parts, that means capturing what worked and what did not, updating your critical parts list, adjusting stocking levels or locations, and refining your playbook and contracts. Resilience is not a oneŌĆætime project; it is a continuous program.

Emergency DCS parts strategies compete for budget with many other priorities. You will need a way to demonstrate value beyond ŌĆ£it feels safer.ŌĆØ

The resilience modeling work in ScienceDirect proposes two metrics that can be repurposed effectively: a timeŌĆæsensitive demand fulfillment rate and an investment return ratio. Translated into DCS terms, the first becomes the percentage of critical failure events where you restored full function within your target recovery time. The second becomes the ratio between the avoided downtime cost (production, service level penalties, regulatory or safety risk) and the total cost of building and operating your emergency spares and logistics capability.

Supply chain and inventory management literature also provide practical financial anchors. If carrying costs are on the order of 20 to 30 percent of inventory value per year, you can compare that to the cost per hour of lost production or critical service. If a single multiŌĆæhour outage avoided by having a spare on hand pays for several years of carrying cost, the business case becomes straightforward.

A concise way to organize these ideas is shown below.

| Dimension | What It Tells You | Example In A DCS / UPS Context |

|---|---|---|

| TimeŌĆæsensitive fulfillment | How often you meet your recovery time targets | Share of critical controller failures recovered within 4 hours |

| Economic return on investment | Whether spare and logistics spend is justified | Downtime cost avoided versus annual spare inventory carrying cost |

| Supply chain reliability | How dependable your external partners are | Fraction of emergency orders shipped and delivered as contracted |

| Inventory efficiency | How well you balance availability and carrying cost | Inventory turns and obsolescence for DCS and UPS spare stock |

Analyses compiled by Sophus and others show that better data integration and forecasting can simultaneously reduce inventory and improve serviceŌĆöinventory levels lowered by roughly 30 percent alongside fill rate improvements of about 10 percent. That kind of tradeoff is precisely what you want for DCS spares: fewer idle, obsolete parts on shelves, paired with faster and more reliable availability when you actually need a module in the middle of the night.

There is no universal number, but the decision should be driven by criticality and downtime cost rather than habit. Start by identifying components whose failure would immediately affect safety functions or essential loads, and estimate the cost of an hour of downtime for each. Then compare that to the annual carrying cost of holding a spare, using inventory carrying cost benchmarks from supply chain research. In many cases, a small set of highŌĆæimpact parts will easily justify onŌĆæsite stock, while less critical items can be held at a regional hub or relied on from OEM stock with contractual leadŌĆætime guarantees.

Most organizations adopt a hybrid. OEMs and distributors play a crucial role in holding broad, multiŌĆæcustomer inventories and managing obsolescence, while your internal stock focuses on highŌĆæcriticality parts and fleetŌĆæspecific modules. Research cited by the Business Continuity Institute and summarized in Inbound Logistics shows that many companies lack clear visibility into whether they will be prioritized by suppliers during disruption. That is a strong argument for holding at least some of your own emergency stock and for negotiating explicit emergencyŌĆæresponse terms with your OEMs instead of assuming they will always have exactly what you need.

The answer depends on your process and regulatory environment, but resilience research suggests treating timeŌĆæsensitive demand separately from routine orders. For loads tied to safety or critical services, it is reasonable to express targets in hours from failure to restoration and to engineer your spares and logistics network accordingly. That may mean onŌĆæsite stock for certain modules, regional hubs with sameŌĆæday delivery for others, and air express agreements for rare but critical items. The important thing is to define those targets explicitly, measure performance against them, and adjust stocking and contracts based on real incident data.

Effective emergency DCS parts delivery is not about stockpiling everything everywhere. It is about understanding your real failure risks, building a lean but robust spares portfolio, and wiring it into a resilient logistics and governance framework so that when a critical module fails, your next moves are automatic, fast, and reliable.

Leave Your Comment