-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Gas and steam turbines sit at the heart of many industrial and utility power systems. Mechanically, a well-maintained turbine can run for decades, but its control panel rarely ages as gracefully. Obsolete controllers, failing cards, and ŌĆ£black boxŌĆØ logic are increasingly common root causes behind forced outages, missed starts, and awkward workarounds that undermine reliability and safety.

As a power system specialist focused on critical power and protection, I look at turbine controls the same way I look at UPS systems and inverters: they are part of the non-negotiable reliability backbone. When a gas turbine is your black-start source, your process driver, or a major piece of your generation portfolio, a control panel replacement is not just a controls job; it is a power-system reliability decision.

The good news is that you are not locked into a single vendor or architecture. Modern alternatives range from OEM-specific controllers to DCS-centric solutions, PLC-based designs, and selective modernization of legacy panels. The challenge is choosing an option that actually reduces your risk, supports future uprates and digital initiatives, and fits within your power protection strategy instead of complicating it.

This article walks through the key decision points and practical options, drawing on field experience and industry guidance from sources such as ASME, Allied Power Group, Control.com, Petrotech, Prismecs, Emerson, GE Vernova, Valmet, Siemens Energy, Woodward, and others.

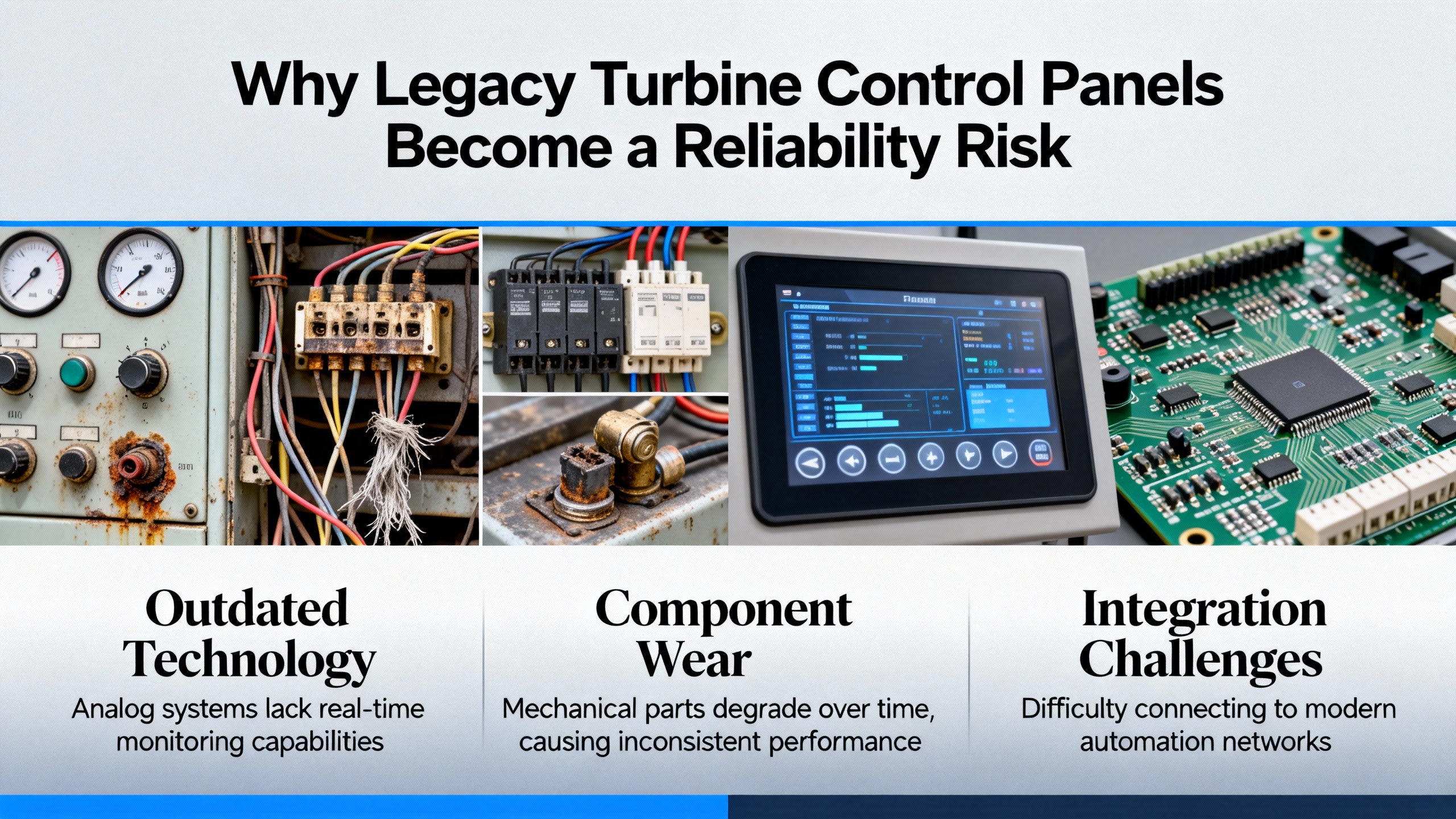

Gas and steam turbines often have a useful life of 30 years or more, while their control systems typically become obsolete much sooner. Woodward notes that obsolete controls make it difficult or impossible to obtain technical support, replacement parts, and even basic training. At that point, a single failed card can jeopardize a unit that is otherwise mechanically sound.

Operators see the symptoms long before anyone budgets for a replacement. Spare power supplies and servos sit on the shelf for a decade because OEM stock is limited and expensive. TC&E, a specialist focused on GE industrial gas turbine controls, highlights that spares older than about five years should be refurbished and rotated with in-service components, because electronic parts degrade in storage. In practice, many plants discover this only when a supposedly ŌĆ£goodŌĆØ spare fails on installation.

Another common problem is the opaque, ŌĆ£black boxŌĆØ nature of first-generation digital controls. At K+S KALI GmbHŌĆÖs potash plant in Germany, the original 1990s turbine automation for several Solar Taurus 60S units had minimal diagnostics and poor transparency. According to ValmetŌĆÖs retrofit case study, operators could not see why start sequences aborted or where faults originated. The upgrade to Valmet DNA in 2015 replaced that black box with an open platform that integrated automatic control, vibration and overspeed protection, alarms, and trend data. Operators gained clear visibility into turbine behavior and could resolve issues more quickly.

Obsolescence is not just a maintenance annoyance; it is a system risk. When a black-start gas turbineŌĆÖs control panel is unsupported, plant-wide resilienceŌĆöincluding UPS systems, switchgear, and process loadsŌĆödepends on electronics that no longer have a safety net. A case study from Petrotech on a 25 MW GE Frame 5 black-start unit in New York makes the point: replacing an obsolete excitation and fuel regulation scheme with modern digital control significantly improved starting reliability and operational flexibility for two large steam units tied to that turbine.

For many sites, the real question is not whether to replace the panel, but how to do it in a way that genuinely improves reliability instead of simply trading one form of lock-in or obsolescence for another.

Before you compare specific vendors or architectures, you need clarity on how the turbine must perform and how much risk your operation can tolerate. An experienced engineer on the Control.com forum summarized the starting point succinctly: define how the unit will be operated and what level of reliability you really require.

A turbine that runs continuously, essentially 24 hours a day year-round, supports a very different business case than a unit that starts only for peak periods or backup service. For continuous-duty units, high-reliability control architectures with redundant processors are often justified. For infrequently used units, full-blown triple modular redundant (TMR) controls may be overkill.

Redundancy choices usually fall into three broad categories: simplex (non-redundant), dual-redundant, and TMR. Each has distinct pros and cons.

| Redundancy architecture | Typical use case | Advantages | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplex (single controller) | Small industrial drives, peaking units where occasional trips can be tolerated | Lowest capital cost; simpler spares and maintenance; fewer components to age and fail | Any major controller failure typically trips the turbine; maintenance often requires outages; limited tolerance to faults |

| Dual-redundant | Mid-critical services, some peakers and cogeneration units | Some fault tolerance; can ride through certain failures; lower cost and complexity than TMR | Many failures still force trips; online replacement capabilities are limited compared with TMR systems |

| TMR (triple modular redundant) | Baseload or grid-critical units, high-value process drives | High availability; many cards can be replaced while running; voting logic masks single failures | Hardware, spares, and lifecycle support cost rise sharply; more total component failures over time simply because there are more parts |

The Control.com discussion emphasizes that TMR systems do not make individual cards more reliable. The failure rate per card stays roughly the same, but TMR systems contain approximately three times as many components, so the total number of failures in the system increases. The benefit is that most of those failures do not cause trips, and you can replace failing modules online.

The suitability of simplex or dual-redundant architectures depends on how painful a forced outage is for your operation. If a trip causes lost production that is acceptable a few times per year, simplex with a rock-solid maintenance plan may be enough. If even a short outage has high financial or safety consequences, TMR or carefully designed dual-redundant architectures start to look less expensive in total cost of risk.

Once you know your operating profile and redundancy requirements, the next decision is who will actually deliver and support the system. Both Control.com contributors and providers like Emerson and Valmet stress that the hardest part is not the hardware; it is field execution.

Removing the old panel, installing the new system, integrating it with existing mechanical and electrical systems, and commissioning the unit back into service are where many projects stumble. It is wise to place more weight on a supplierŌĆÖs track record with similar retrofits than on brand labels alone. The Control.com guidance is blunt: get references and verify that previous upgrades were completed on time, within budget, and that the units run reliably years later.

From a power-system perspective, this is also where you align the control upgrade with your UPS, DC, and protection strategy. A new DCS or OEM controller typically adds servers, network switches, and safety logic solvers that all depend on high-quality, battery-backed power. Making sure the integrator understands your critical power designŌĆöand not just turbine logicŌĆöis essential.

With those strategic decisions on reliability and vendor capability in view, you can evaluate the main architectural options for replacing a gas turbine control panel.

Most major turbine OEMs offer their own standardized control platforms. Unisys GroupŌĆÖs overview of gas turbine controls cites GE Mark VIe, Siemens T3000, and ABB Symphony Plus as typical examples. These systems are tailored to specific turbine models and include purpose-built modules, such as GEŌĆÖs safety-rated controllers that support Safety Integrity Level (SIL) requirements for protection functions.

GE VernovaŌĆÖs Mark VIe upgrade portfolio illustrates the OEM model clearly. Mark VIe can be applied across a wide range of GE frames, including 6F, 7F, 9F, 6B, 7E, and 9E units, and even to some legacy Alstom frames. It also extends beyond the gas turbine itself to heat recovery steam generators, steam turbines, and generators, enabling an integrated plant control environment. Firmware and applications are developed specifically for those turbines, and the platform is positioned as a way to standardize controls across a mixed fleet while reducing obsolescence risk.

The strengths of OEM controllers include deep turbine-specific knowledge embedded in control algorithms, direct alignment with OEM upgrade packages such as Advanced Gas Path hardware or performance improvement kits, and clear pathways for maintaining regulatory compliance and support. For plants with long-term service agreements or heavy reliance on OEM engineering support, this is often the least disruptive path.

The trade-offs are mostly around flexibility and cost. TC&EŌĆÖs experience with GE Mark platforms is a good caution: OEMs may recommend upgrading from older systems such as Mark IV or Mark V to Mark VIe for relatively small changes, not because the old hardware cannot handle the function, but because they no longer maintain expertise in the legacy logic. The result can be a large capital project where a targeted solution would have sufficed. OEM systems also tend to be more closed, with limited ability for plant engineers to modify logic or integrate non-OEM hardware without going through the vendor.

Distributed Control Systems (DCS) consolidate multiple subsystemsŌĆöturbines, boilers, balance of plantŌĆöinto a unified automation platform. Unisys highlights platforms like Emerson DeltaV, Honeywell Experion, and Yokogawa CENTUM as common choices. EmersonŌĆÖs Ovation DCS, for example, has been installed on more than 1,500 steam and gas turbine control systems according to company presentations, and is often used as the central nervous system for generating stations.

ValmetŌĆÖs modernization of K+S KALIŌĆÖs Solar Taurus fleet is a concrete example of DCS-centric turbine control. The Valmet DNA platform integrated automatic turbine control and regulation, vibration and overspeed protection, emission control, and start-up and shutdown sequencing. It also provided rich alarm and trend capabilities and supported more than 50 communication protocols, making it straightforward to link the turbines into the existing plant control system.

The benefits of this approach are substantial. Operators at the Zielitz plant reported that they could now see turbine states during start and stop sequences, understand why sequences were canceled, and locate root causes more quickly. Emissions performance improved as well; the retrofitted turbines operated near 16 mg per cubic meter of NOx against a German legal limit of 75 mg per cubic meter, verified periodically by an independent testing body. Process stability and efficiency improved enough to gain roughly 200 kW of additional turbine capacity, which reduced reliance on grid imports.

EmersonŌĆÖs work on turbine mechanical upgrades complements this model. Their Testable Dump Manifold trip system provides triple-redundant hydraulic fault tolerance with de-energize-to-trip behavior and two-out-of-three voting logic, integrated with the Ovation DCS. Combining modern digital control with robust mechanical trip systems yields both better data and higher safety integrity.

The main downsides of a DCS-centric strategy are scope and complexity. Migrating turbine control into a plant-wide DCS is often a larger project than a like-for-like panel replacement. It demands careful management of interfaces, extensive testing, and integration into your cyber security architecture. From a power protection standpoint, a DCS solution will likely increase dependence on server-class hardware and network infrastructure, all of which must be fed from reliable UPS and DC sources.

Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) sit between OEM-specific controllers and large DCS platforms. Unisys describes PLCs such as Siemens S7, AllenŌĆæBradley, and Schneider units as modular, cost-effective industrial computers well suited to smaller turbines, retrofits, or hybrid PLC plus DCS setups. They are typically programmed in ladder logic or structured text and offer high-speed I/O, redundancy options, and flexible custom logic.

PLCs become particularly powerful when combined with an open architecture philosophy, as promoted by Petrotech. Their approach relies on industry-standard programming environments and non-proprietary hardware. The benefits are easier upgrades, broader sourcing options for spares, and less dependence on a single vendor or proprietary tools. In the New York GE Frame 5 case, Petrotech combined a modern digital excitation system, new turbine fuel regulation, upgraded speed sensors, and an HMI with real-time trending of speed, exhaust temperature, generator voltage, and real power. The result was higher efficiency, improved reliability, and smoother transitions between isochronous and droop operating modes.

A PLC-centric design is often attractive for simple mechanical drive turbines, process units, or smaller cogeneration systems where a full DCS would be overkill. It also works well in hybrid architectures where a PLC handles fast local control and a higher-level DCS coordinates power plant-wide functions.

The main risks are engineering quality and functional safety. PLC platforms are flexible by design, which means the burden of getting the application logic, diagnostics, and safety functions right falls heavily on the integrator. Safety Instrumented Systems compliant with IEC 61508 and Safety Integrity Levels can be implemented on suitable hardware, but they must be engineered with rigor. Unisys emphasizes the role of integrated safety layers, such as automated emergency shutdown and independent safety logic, to ensure that failures lead to safe states even in complex configurations.

Between pure OEM and fully custom PLC solutions lies a large ecosystem of independent turbine control specialists and upgrade providers. TC&E (a division of AP4 Group), Petrotech, Woodward, PSM, Siemens Energy, Prismecs, and others all appear in industry literature with differing focuses.

TC&E concentrates on GE Mark platforms and makes a strong case that an OEM-recommended control upgrade is not always technically necessary. They routinely add features such as steam augmentation to existing Mark IV systems by writing new logic rather than replacing the entire platform. They also help plants locate legacy components, refurbish older spares, and add modern HMIs to Mark IV systems. For many operators, this kind of targeted modernization extends control system life and reduces cost without sacrificing functionality.

Petrotech and Prismecs position themselves as broader engineering partners. PetrotechŌĆÖs work on turbine efficiency emphasizes advanced digital control systems as a key lever, with microprocessor-based controls optimizing fuel flow, excitation, and speed in real time and supporting open, non-proprietary architectures. Prismecs highlights innovations such as digital twins and predictive maintenance, which rely on rich real-time data and accurate models of turbine behavior. Both approaches treat the turbine control system as part of a larger digital strategy rather than an isolated box.

Woodward focuses on replacing obsolete controls on gas turbines, steam turbines, and compressors with modern, supported platforms. Their offering is notable for emphasizing owner self-sufficiency: configuration tools and training are designed so plant staff can operate, maintain, and adapt their control systems over time instead of being captive to external service providers.

The advantages of working with independent specialists include tailored solutions, flexibility in hardware choice, often lower lifecycle cost, and the ability to preserve valuable parts of existing systems. The risks, as both Control.com contributors and Emerson project teams note, lie in execution quality. Field experience, reference projects, and long-term support capability should be scrutinized as carefully as the technical proposal.

In some situations, full control system replacement is neither necessary nor feasible. Selective modernization can address the most pressing risks while deferring a complete re-control.

TC&EŌĆÖs work on older GE platforms shows how much can be done by adding modern HMIs, updating logic, and replacing high-failure components such as power supplies and servos. Their recommendation to regularly refurbish spares older than about five years and rotate them with in-service units is a practical life-extension tactic for aging Mark IV, Mark V, and Mark VIe systems.

On the mechanical protection side, EmersonŌĆÖs turbine trip manifold upgrades demonstrate another partial modernization path. Replacing aging hydraulic trip components with a triple-redundant, testable dump manifold integrated into an existing or new DCS improves overspeed and trip reliability without touching the main control logic.

These partial approaches work best when the underlying controller is still supportable or when the plant is planning a staged migration. They can buy time and reduce risk, but they should be evaluated honestly against the pace of obsolescence. At some point, replacement becomes less risky than stretching a platform beyond its intended life.

Control panel replacement decisions increasingly intersect with performance uprates and efficiency initiatives. An ASME paper on industrial gas turbine uprates describes a wide range of modifications: increased compressor mass flow, higher firing temperature, dimensional scaling, recuperation, and higher cycle pressure ratios. Each of these changes increases output or efficiency, but they also stress components and narrow operating margins.

Modern control systems are central to making uprates work without compromising life or safety. Higher firing temperatures demand precise turbine inlet temperature control, blade cooling management, and strict adherence to life consumption models. Increased mass flow and pressure ratio alter compressor surge margins and off-design behavior, which must be monitored and controlled carefully. Combined-cycle plants see significant changes in exhaust energy, which Power Engineering notes can materially affect heat recovery steam generator behavior, drum levels, safety valve lift points, and steam turbine swallowing capacity.

Digital control platforms with advanced analytics, as described by Prismecs and Petrotech, help manage these complexities. Digital twinsŌĆövirtual replicas of turbines driven by live dataŌĆöenable scenario simulation and early detection of anomalies. Predictive maintenance algorithms using vibration, thermography, and process data, like those highlighted by Allied Power Group and MD&A in their maintenance and overhaul discussions, rely on consistent, high-quality measurements and event logging from the control system.

In practical terms, if your long-term plan includes performance improvement packages such as GE VernovaŌĆÖs PIP for B and E-class units, PSM retrofits, or low-NOx combustion upgrades, you should ensure that the chosen control architecture can support those future states. An obsolete panel that barely manages current conditions will not gracefully handle higher firing temperatures, increased mass flow, or more aggressive low-emission combustion without either major rework or new limitations.

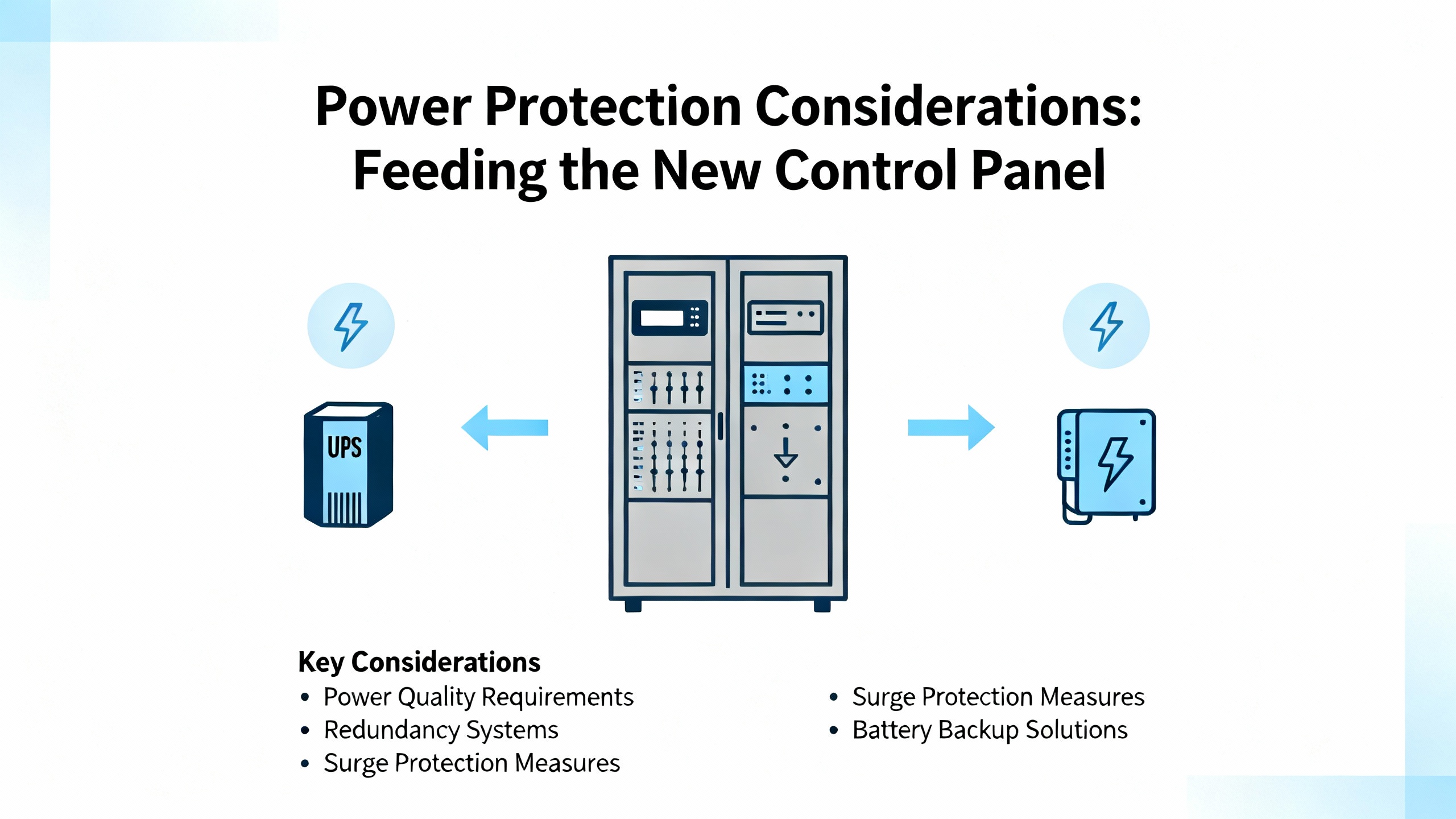

From a power-system reliability perspective, replacing a turbine control panel is inseparable from the question of how it is powered and protected. Modern control solutions use more digital components than the analog or early-generation systems they replace. Servers, redundant controllers, safety logic solvers, managed switches, and historian nodes all rely on clean, stable power.

In most industrial plants, critical controls are fed from DC battery systems or AC backed by static UPS and inverter systems. When you upgrade a turbine control panel, you should revisit the control power design with the same rigor you apply to a critical data center.

The practical questions are straightforward. The first is whether the existing DC or UPS system has enough capacity and redundancy to handle the new control loads plus a margin. DCS or OEM platforms often require more continuous power than legacy racks, and the addition of auxiliary equipment such as vibration monitoring racks, network firewalls, and secure remote access gateways can be significant. The second is ride-through capability. The control system, protective relays, excitation, and associated communication infrastructure need to stay alive through realistic fault and switching scenarios on the plant auxiliary system.

Safety system architecture also matters. Unisys emphasizes the role of independent Safety Instrumented Systems and emergency shutdown logic that default to safe states on power loss. UPS and DC designs should align with this principle so that loss of one feed leads to controlled shutdown rather than undefined behavior.

Modernization projects described in Power Magazine add a digital protection dimension: cyber security becomes the counterpart to UPS protection in the electrical domain. Moving from isolated, proprietary networks to Ethernet-based, information-enabled controls increases exposure to external threats. NERC CIP and industry security standards push operators toward defense-in-depth approaches, combining network segmentation, hardened devices, secure remote access, and robust vendor security practices.

In summary, a well-designed control panel replacement does not only deliver a new set of logic diagrams. It also strengthens the overall reliability chain, from the battery room and UPS through the network to the controller and the turbine itself.

The main control panel replacement paths can be thought of as four families. None is universally best; the right choice depends on plant context, risk tolerance, and long-term plans.

| Replacement path | Best suited for | Main strengths | Key watchpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| OEM turbine-specific controller (for example, Mark VIe, T3000) | Fleets with strong OEM relationships, units under long-term service agreements, plants planning OEM hardware uprates | Deep turbine-specific models; integrated with OEM upgrades; standardized across fleet; clear support path | Vendor lock-in; limited openness; potential for upgrades driven by OEM capability gaps rather than plant need; higher capital and licensing cost |

| DCS-centric turbine control | Large plants seeking unified automation across turbines, boilers, and balance of plant; sites targeting advanced analytics and emissions optimization | Single platform for plant control; rich alarms and trends; easier integration of predictive maintenance and digital initiatives; proven in many retrofit case studies | Larger project scope; more dependence on server and network infrastructure; requires strong cyber security and UPS design; integration effort can be high |

| PLC-based or hybrid independent solutions | Small to mid-size units, mechanical drives, cogeneration, or sites wanting maximum flexibility and open hardware | Cost-effective; flexible logic and hardware; easier to avoid technology lock-in; good fit with open-architecture philosophies such as those promoted by Petrotech | Application quality highly dependent on integrator; safety functions must be engineered carefully; may require more in-house expertise to maintain |

| Partial modernization of legacy panel | Units with constrained outage windows or limited budgets where the underlying controller is still supportable | Lower immediate cost; targeted risk reduction; extends life of existing systems; can be staged toward a full replacement later | Does not eliminate obsolescence; some high-risk components may remain; may complicate future complete migrations if not planned carefully |

The best choice often emerges when you align the replacement path with a clear performance and reliability roadmap rather than treating it as a one-time hardware swap.

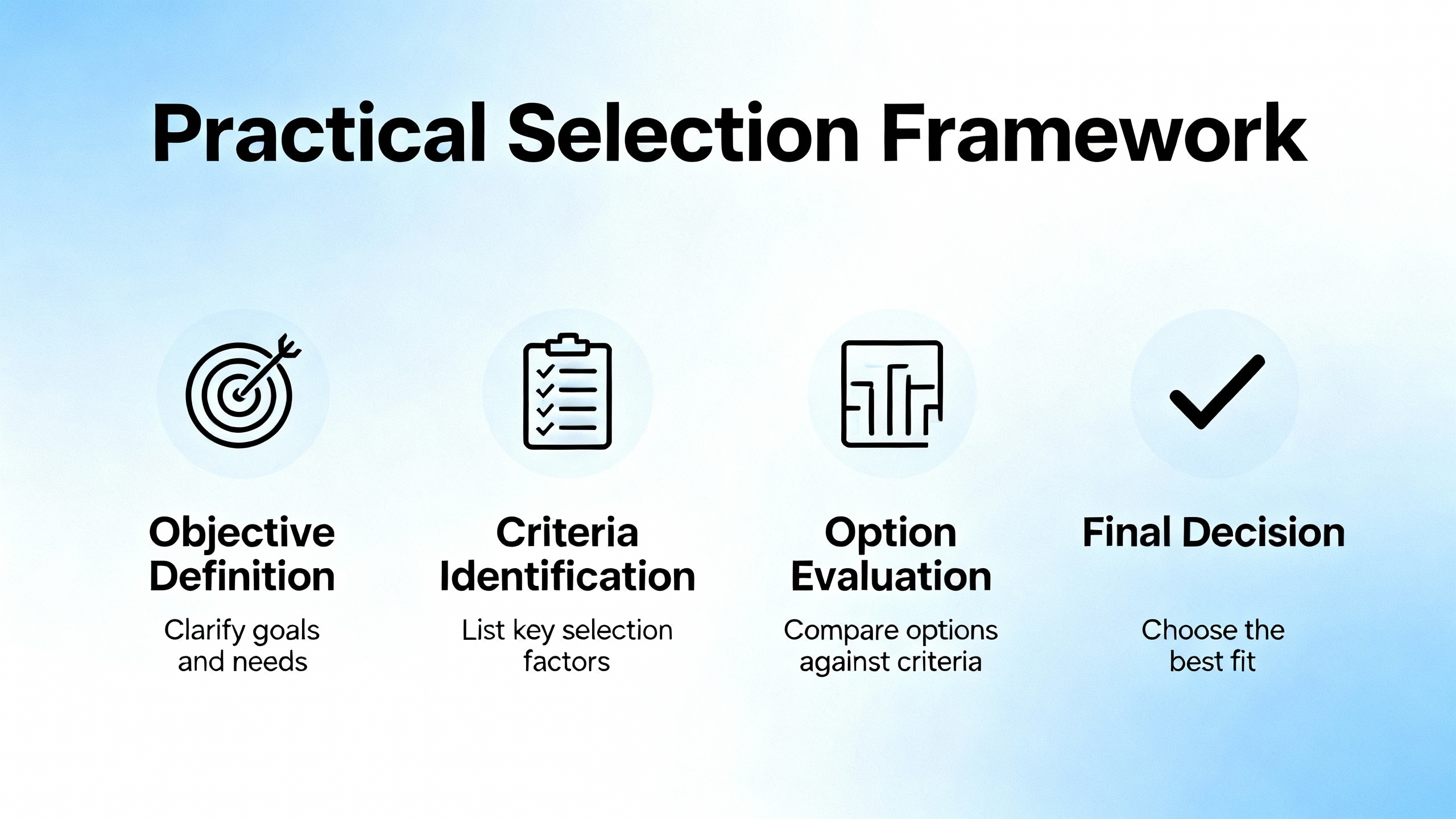

Drawing on best practices from Control.com, Emerson, Valmet, Power Magazine, and multiple upgrade providers, a practical framework for selecting and implementing a control panel replacement has several elements.

First, clarify objectives beyond ŌĆ£replace the obsolete panel.ŌĆØ Are you primarily chasing reliability and maintainability, planning performance uprates, reducing emissions, standardizing across a fleet, or enabling modern analytics and predictive maintenance? A modest peaking unit that needs reliable starting will drive very different choices than a baseload combined-cycle block that is a cornerstone of your grid or industrial power supply.

Second, refine the reliability and redundancy strategy in the context of your whole power system. That includes the turbine itself, black-start obligations, UPS and DC systems, critical loads, and grid code or process constraints. Use that to define whether simplex, dual, or TMR architectures are appropriate and what level of safety integrity you need in emergency shutdown and safety layers.

Third, decide on the architectural familyŌĆöOEM controller, DCS-centric, PLC-based, or partial modernizationŌĆöand then down-select vendors within that family. For each candidate, ask for references on similar turbines and applications, and verify them. Control.com contributors repeatedly stress that due diligence on field performance and long-term support matters far more than the brand printed on the controller.

Fourth, insist on thorough design and testing. ValmetŌĆÖs project for K+S KALI included a factory acceptance test in Finland with participation from both the plant and a specialist turbine service company, allowing the control philosophy to be adjusted before site installation. Emerson similarly emphasizes stakeholder engagement and careful planning of installation, trip systems, and hydraulic interfaces. Whether you choose OEM, DCS, or PLC, a robust test plan and realistic simulation of process conditions are essential safeguards.

Fifth, integrate power protection and cyber security into the scope from day one. Review DC and UPS capacity and redundancy, ensure that control and safety power feeds support your desired fail-safe behavior, and align with your broader plant standards. On the cyber side, leverage reference architectures where available and apply layered security around the new control assets, particularly if remote access or cloud analytics are in scope.

Finally, invest in operator and maintenance training. Power MagazineŌĆÖs modernization case studies show that modern controls can dramatically reduce nuisance trips and failed starts, but only when operators understand the new system, trust its diagnostics, and know how to respond to alarms. Training should cover both the control application and the surrounding protection and power infrastructure.

No. OEM controllers such as Mark VIe or T3000 are proven options, and they offer strong integration with OEM hardware upgrades, but they are not the only viable choice. Independent specialists and DCS or PLC-based solutions have been successfully deployed on many gas turbines, as shown in case studies from Valmet, Petrotech, and others. The decision should be based on reliability needs, supportability, openness, and total lifecycle cost, not just on OEM marketing claims. The Control.com forum explicitly cautions users to challenge assertions that only the OEM can provide suitable control and protection.

TMR architectures shine where continuous operation is critical and forced outages are extremely costly. They are common on baseload generation units and high-value process drives. TMR lets you replace many failing cards while the turbine continues running, but it also means more hardware to purchase, stock, and maintain, and more total component failures over the life of the system simply because there are more parts. For peaking or backup units where some trips are tolerable, a well-designed simplex or dual-redundant system may offer better value.

There is no universal expiration date, but there are clear warning signs. Difficulty sourcing parts, frequent nuisance trips, opaque diagnostics, and a shrinking pool of engineers who understand the platform all point toward rising risk. TC&EŌĆÖs advice to refurbish and rotate spares older than about five years illustrates how quickly component degradation becomes a concern. Woodward notes that once a control system becomes obsolete, support, parts, and training are all compromised. If your panel is in that category and the turbine is critical to your operation, planning a replacement or deep modernization is almost always safer than hoping the next outage does not happen at a bad moment.

Modernizing a gas turbine control panel is one of the most leveraged reliability investments you can make in a power system. If you align the replacement with your operating profile, uprate plans, power protection design, and digital ambitionsŌĆöand choose partners with real field experienceŌĆöyou transform the control panel from an aging weak link into a resilient, future-ready asset.

Leave Your Comment