-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When you design or upgrade industrial and commercial power systemsŌĆöUPS plants, inverter-based backup, static transfer switches, and power quality equipmentŌĆöthe choice between a Distributed Control System (DCS) and a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) is not just an automation question. It is a reliability question. The control platform you choose will directly influence how your power system behaves during a fault, how quickly you can restore capacity after maintenance, and what it costs to support the installation over 10 to 20 years.

Publications such as Plant Engineering, ISA, RealPars, and several automation forums consistently emphasize that modern PLC and DCS platforms have converged in many capabilities. That convergence is helpful, but it also makes the choice less obvious. In power applications, where a single misbehaving controller can drop a critical bus or mismanage a UPS cluster, you need a structured way to decide.

In this article, I will walk through the selection criteria that matter most in power reliability work and ground them in guidance from sources like ISAŌĆÖs Honeywell-authored control-system selection article, Plant EngineeringŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Six steps to choose between PLC and DCS,ŌĆØ and technical discussions from Control.com, Panelmatic, and others. The focus is practical: how to decide what is appropriate for your UPS, inverter, and power protection systems, and when hybrid architectures make the most sense.

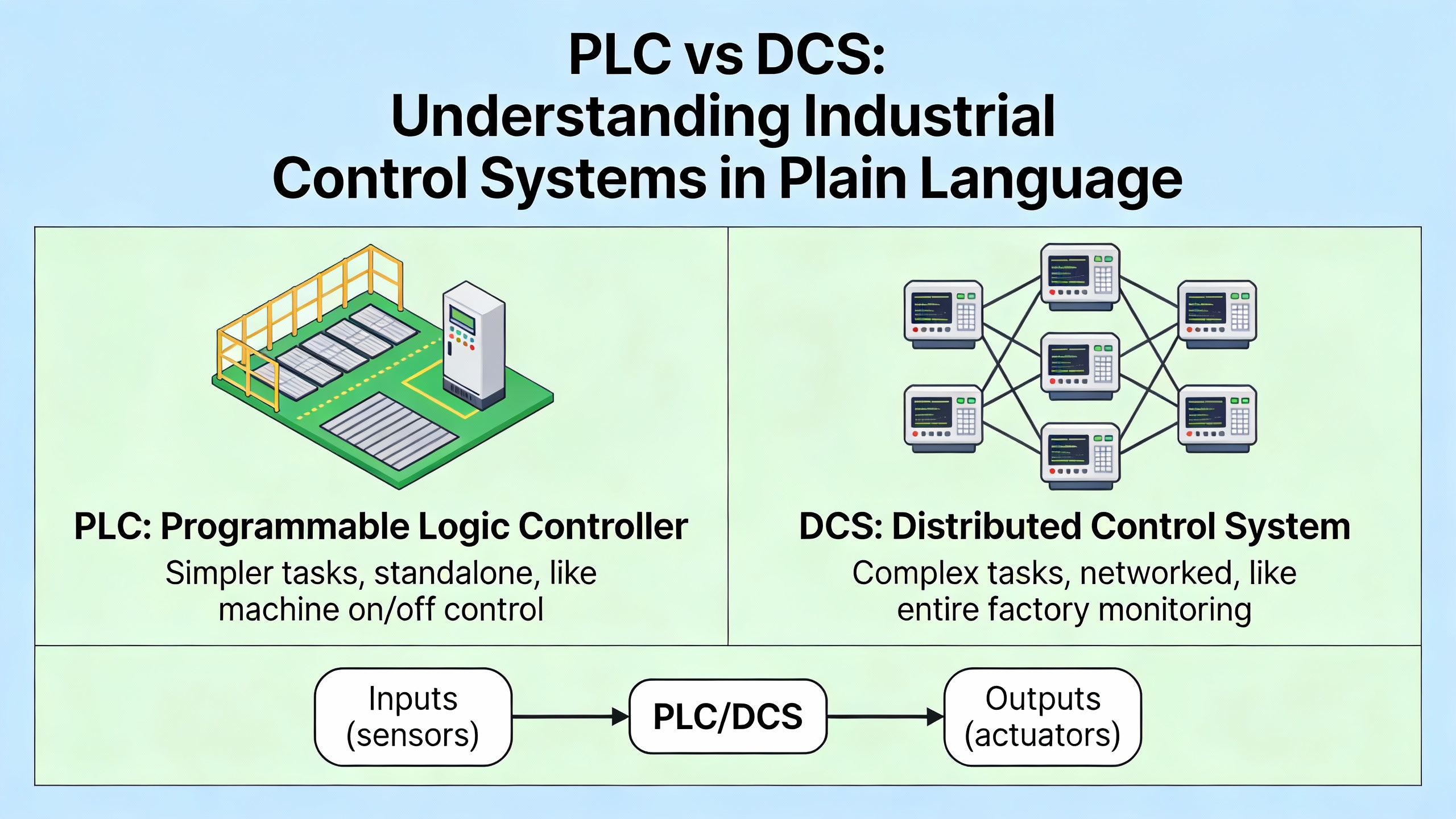

A PLC is essentially a rugged industrial computer designed for fast, deterministic control of machines and localized processes. According to historical accounts summarized by RealPars and PLC Technician training material, the PLC was originally created by Dick Morley and commercialized through Modicon to replace hard-wired relay panels at automotive plants. Early installations at GM reportedly involved over $1,000,000 in PLCs, primarily running ladder logic to perform discrete on/off control that had previously been done by relays and contactors.

A DCS, by contrast, is a plant-wide control architecture made up of multiple distributed controllers, engineering stations, and operator workstations connected by a dedicated control network. RealPars, PLCTechnician, Panelmatic, and SWIDCH all describe DCS platforms as being optimized for large, continuous or batch processes and for coordinating many units across a facility. The DCS typically includes an integrated HMI, alarm management, historian, and often batch or advanced control functions within the same vendor ecosystem.

A simple way to think about it, reflecting the distinctions laid out by RealPars and the PLC Technician material, is that PLCs were born to control individual machines, while DCS systems were born to control whole plants. Over time, both technologies have evolved and overlapped. Plant Engineering notes that in the last fifteen years, PLC plus SCADA combinations have gained memory, speed, redundancy, and shared variable databases, while DCS vendors have added discrete control languages and cut hardware prices. The result is a blurred boundary, especially in process industries.

For power systems, that blurred boundary means you can implement a fully functional UPS and generator control scheme with either a network of PLCs plus SCADA or a DCS-style platform. The decision hinges on the nature of the process, the degree of integration you need, your availability targets, and the skillset and budget available to support the system over its life.

Although the literature often focuses on chemical plants and HVAC systems, the behaviors carry directly into power reliability work.

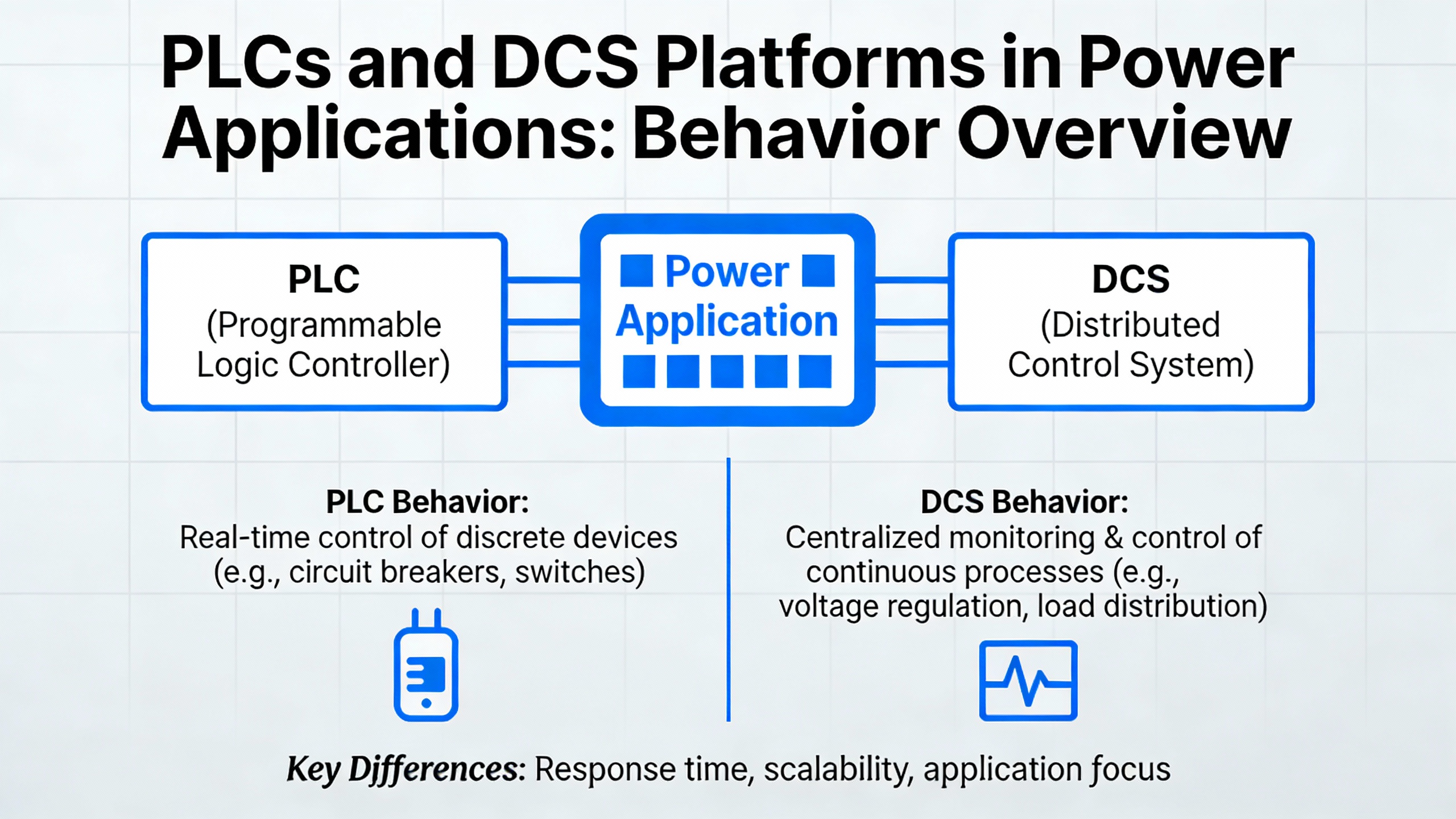

PLCs excel at high-speed, discrete logic. SWIDCH notes that PLCs are commonly used in discrete automation where signals are largely on or off, like automotive assembly lines dominated by digital states with only limited analog. Plant Engineering adds that PLCs can handle very fast scanning of several thousand I/O points in roughly a tenth of a second, which is ideal for emergency shutdowns and high-speed interlocking. Translated to a power system, that profile fits applications such as automatic transfer switch interlocks, generator start sequences, fast breaker logics, and machine-level controls inside a UPS or static switch.

DCS systems excel where there are many analog signals, numerous PID loops, and a need for plant-wide coordination. SWIDCH and Zeroinstrument both highlight that DCS architectures are better suited to continuous processes with many analog loops, such as power plants and refineries. Panelmatic and the Control.com forum discussion emphasize that DCS platforms come with built-in continuous and regulatory control, batch control, alarm management, trending, and often advanced control functions. In a power plant, or in a campus-scale microgrid with multiple generation sources, these capabilities support coordinated load sharing, tie-line control, frequency and voltage regulation, and automated abnormal condition management.

In power protection work, most real installations are not purely one or the other. An industrial facility might use PLCs inside switchgear lineups and UPS skids, supervised by a DCS or SCADA system in a control room. A large data center may choose a DCS-like platform or a large SCADA system for overall monitoring and alarm management, with PLCs handling fast local logic at breaker or UPS level. This hybrid approach matches the pattern described by Zeroinstrument and Plant Engineering, which both note that hybrid architectures using DCS for core process areas and PLCs for fast or discrete subsystems are common and effective.

The first question is about process character. Sources such as the Plant Engineering flowchart and the SWIDCH discussion converge on the same point: if your application looks like a continuous process with many analog loops, a DCS is usually favored; if it looks like a discrete or machine-centric process, a PLC-based solution often makes more sense.

In the context of power systems, a small commercial building with a single medium-voltage switchboard, one UPS, and a standby generator typically behaves like a collection of discrete devices. You have discrete statuses such as breaker open or closed, UPS on or off, generator running or stopped, and a modest set of analog measurements for voltage, current, and power factor. The number of control loops is limited, and the primary control actions are sequences and interlocks. SWIDCH points out that PLCs are particularly suitable when discrete signals dominate and analog signals are relatively few. In such a case, a PLC or small network of PLCs with an HMI or light SCADA is usually sufficient and cost-effective.

At the other end of the spectrum, consider a larger campus or industrial complex with multiple medium-voltage feeders, several UPS plants, on-site generation, and possibly energy storage. The system might require continuous management of power flows, dynamic load shedding, peak shaving, and coordination with utility grid codes. Zeroinstrument and Control EngineeringŌĆÖs guidance indicate that when I/O counts are high, analog controls are numerous, and the system is geographically spread, a DCS-oriented platform is more appropriate. That conclusion is reinforced by Plant EngineeringŌĆÖs observation that DCS architectures handle large numbers of control loops more gracefully by distributing them across multiple CPUs rather than overloading a single controller.

A practical way to apply this is to estimate the nature and volume of control loops. If the majority of your control logic is on/off sequences, permissives, and interlocks, and if your analog processing can be handled by a few dozen simple PID or limit loops, a PLC-based system is likely adequate. If you are approaching hundreds of analog control loops for voltage, frequency, load sharing, and power quality across multiple buses and sources, the DCS advantages in distributed processing and integrated operator support begin to matter.

The second major decision point is about integration and operational workflows. The DCS literature, particularly from ISAŌĆÖs guest article by a Honeywell Process Solutions product manager and the Control.com forum discussion, emphasizes that a DCS is not just hardware. It is an integrated environment for engineering, operations, and maintenance.

The Control.com discussion lists a broad set of functions that are typically built into a DCS: continuous and regulatory control, ISA S88 batch control, dynamic simulation, advanced control capabilities such as neural networks or model predictive control, redundant networking, alarm reporting and logging, material and product tracking, statistical process control, automatic loop tuning, multiple I/O drivers, and graphical operator interfaces with trending and interface to desktop tools like spreadsheets. Plant Engineering echoes this integrated view, noting that a DCS uses a single shared database for logic, HMI, alarms, and historian, which simplifies changes and tailors the environment to operator needs.

RealPars and the PLC Technician material add that DCS platforms link control logic and monitoring graphics very tightly, often allowing HMI pages to be auto-generated from control configurations. This linkage significantly reduces manual engineering time for large systems where every loop needs visibility, trending, and alarm management.

By contrast, PLC solutions generally require you to assemble your own ecosystem. Panelmatic describes PLCs as controllers whose programming and monitoring environments are typically separate and must be designed independently. Zeroinstrument and Control Engineering note that PLC-based architectures often use separate SCADA or HMI packages, a historian from another vendor, and third-party alarm management or reporting tools, connected via open protocols such as Modbus TCP or Ethernet/IP. This offers flexibility and an open architecture, but it shifts the integration burden onto your project team.

In a power system context, the distinction shows up in how operators experience the plant. A large data center or hospital that runs a central control room will benefit from the DCS philosophy: plant-wide views, sophisticated alarm management, a unified historian, and structured navigation so operators can move from one-line diagrams to detailed device faceplates with consistent behavior. ISAŌĆÖs article stresses that DCS selection should prioritize proven yet innovative technology, robustness, and ease of use, including standardized display libraries and pre-built templates that reflect abnormal situation management best practices.

If your power system will not be continuously supervised from a control roomŌĆösay you have a small UPS supporting a single building with only local operator panelsŌĆöthe value of a DCS-style integration is lower. Plant Engineering specifically notes that for systems without full-time operator supervision, such as packaged water or wastewater units, a PLC with local HMI or SCADA is often sufficient and more economical. By analogy, a small standby power system where operators only occasionally interact with the control system fits better in the PLC plus HMI camp.

An instructive example is a campus energy plant that includes several generators, a central UPS plant, and multiple medium-voltage tie breakers. Bringing all of these elements into a unified display, with alarms prioritized and logically grouped by zone and function, becomes a non-trivial engineering task. A DCS or DCS-like system with integrated templates and a unified database can reduce engineering hours and, as the ISA and Control.com sources suggest, provide more robust operation under abnormal conditions. A purely PLC-based solution can achieve the same functionality, but you will be paying for custom integration rather than using built-in platform capabilities.

Reliability and cost over the life of the installation are tightly coupled. Control engineers often focus on hardware price first, but sources like Control Engineering, ISA, and Plant Engineering repeatedly emphasize that total cost of ownership over a 10 to 20 year horizon matters more than the initial hardware bill.

On the reliability front, DCS architectures are designed from the ground up for high availability. The Control.com forum discussion describes how DCS controllers implement real-time executives tailored for bumpless failover. If one controller fails, the backup takes over without upsetting process data or losing critical information needed for batch logic, complex analog schemes, alarm filtering, and equipment allocation. Panelmatic and SWIDCH further note that DCS systems are both distributed and highly redundant, with redundancy often extending to CPUs, power supplies, servers, network switches, and cabling. Panelmatic highlights that a fault in one DCS subsystem usually does not shut down the entire plant, which is a direct benefit in large power systems where you cannot afford a full blackout due to a single controller failure.

PLC-based systems can also be designed with redundancy, but it is often less inherent and requires more engineering. The RealPars article explicitly points out that a single PLC controlling an entire plant is a single point of failure, and cautions against such designs. It also notes that a network of autonomous PLCs, connected by modern communications such as Ethernet and fiber, can approach the robustness of a DCS as long as the network and supervisory system are carefully designed. Plant Engineering acknowledges that PLC plus SCADA architectures can address many DCS applications, but warns that continuity of control and data during failures may not be as guaranteed when control is split between PLCs and external applications.

For power reliability, these distinctions show up most clearly in fault scenarios and planned maintenance. If your facility has a mission-critical UPS and generator plant where any unintended trip is unacceptable, the bumpless failover and distributed control of a DCS may be attractive, especially when combined with built-in alarm filtering and advanced control strategies for load shedding and restoration. For smaller or less critical systems, a simpler redundant or hot-standby PLC arrangement may be sufficient, provided it is engineered and tested thoroughly.

Lifecycle cost is the other half of this question. Control Engineering encourages teams to compare not only hardware price but also engineering hours, licensing, spare parts, maintenance, and upgrade cycles. Plant Engineering provides concrete examples of cost structure differences: PLC ecosystems often rely on local system integrators with day rates around a few hundred dollars, while DCS vendors commonly charge significantly higher day rates for modifications and support. Alternatively, plants can invest in training in-house engineers on the DCS platform, which raises initial cost but can lower long-term total cost.

RealPars adds another dimension by noting that DCS programmers often require specialized skills in databases and IT networking, while PLC programmers are more widely available and typically familiar with ladder logic and newer IEC languages such as function block and sequential function chart. ISAŌĆÖs article notes that DCS engineering tools with bulk configuration and standard templates can reduce repetitive work, which helps offset higher platform costs in larger projects.

In power equipment projects, a practical way to apply this is to consider how often you expect to change or expand the system. Plant Engineering stresses that where frequent modifications are expected, the single integrated database of a DCS simplifies changes and reduces errors, which can justify the premium. In a rapidly evolving microgrid or campus power system where you plan to add feeders, UPS modules, or storage over the years, that integration can save substantial engineering and commissioning effort. In a more static backup system where the topology will not change much after commissioning, the lower initial and modification costs of a PLC-based solution may be more compelling.

Selection is never purely technical. The available skills in your organization, your cybersecurity requirements, and your scalability needs all shape the right answer.

Skill availability is particularly important. RealPars points out that DCS programmers often need experience not only in control logic but also in databases and IT networking, and notes that they can be harder to find. PLCTechnician materials emphasize that PLC skills are widely taught and accessible through structured training programs, and that understanding PLCŌĆōDCS differences is itself a career-strengthening topic. Zeroinstrument and Plant Engineering both recommend selecting a platform compatible with your existing installed base and skillset, or planning to invest in training if you choose a more complex platform.

From a cybersecurity standpoint, Panelmatic notes that DCS platforms, because of their extensive interconnectivity and central visibility, can have higher exposure to cyber-attack. SWIDCH observes that centralized PLC architectures can also be vulnerable, especially when a central controller is compromised. While the research notes do not provide detailed cybersecurity best practices, they underscore that both DCS and PLC systems must be designed with security in mind. Control EngineeringŌĆÖs general guidance suggests favoring platforms that support secure authentication, role-based access, encrypted communications, and structured patch management when critical power infrastructure is involved.

Scalability is the final element of this question. ISAŌĆÖs Honeywell-authored piece advises that a DCS should be able to start from a small footprintŌĆöperhaps a single controller and stationŌĆöand scale to much larger systems with multiple controllers and servers. Zeroinstrument emphasizes that DCS architectures tend to scale more naturally for very large plants and centralized control rooms. PLC architectures scale by networking multiple controllers, which offers flexibility but demands careful design, documentation, and network management to maintain deterministic performance.

In a power context, that means considering whether your initial UPS or generator project is a small standalone system or the first phase of a multi-stage campus energy strategy. If you are building a core plant with plans to add distributed energy resources, additional switchgear lineups, and complex load management over time, starting on a scalable DCS or DCS-like platform can avoid a patchwork of separate PLC projects later. If your project is a single electrical room with one UPS and one generator and no planned expansion, a PLC-based architecture will likely remain adequate for its entire life.

It is helpful to map these criteria to typical scenarios in industrial and commercial power systems, using the patterns and examples described across the research sources.

For a small commercial building UPS and generator system, where the control requirements are limited to starting the generator, transferring load, monitoring a few breakers, and displaying basic alarms and metering, the process is discrete and the loop count is low. SWIDCH and PLCTechnician describe PLCs as ideal for such machine-level and discrete tasks, and Plant Engineering notes that for nonŌĆōcontrol-room-centric operations, PLC plus local HMI or minimal SCADA is generally more economical. In this case, a PLC-based control panel with a simple HMI is usually the right fit.

For a medium industrial plant or hospital central energy plant, the picture changes. Asset-Eyes, in its comparison of PLC, PAC, and DCS, points out that DCS platforms are often preferred for district energy and campus-wide systems, including mission-critical sites like hospitals and data centers. These systems typically have multiple chillers, boilers, generators, UPS modules, and a complex distribution network, all of which must be coordinated. Zeroinstrument notes that DCS platforms are favored where there are many analog loops, tightly coupled unit operations, and a strong need for centralized operation and built-in alarm management and historian functions. At this scale, a hybrid approach is common: a DCS or large SCADA system for plant-wide monitoring and supervisory control, with PLCs embedded in OEM equipment or local switchgear for fast, discrete logic.

For large power generation plants or university-style campus microgrids with multiple generating units, utility interties, and extensive distribution, the case for a DCS becomes stronger. SWIDCH specifically cites power plants as an example of continuous processes with many analog signals and PID loops where DCS architectures are appropriate. Plant EngineeringŌĆÖs criteria around advanced process control and high loop count also point toward a DCS, especially when long delays and tight stability requirements make advanced control techniques attractive. In such environments, the DCS provides a unified framework for voltage and frequency control, turbine and boiler controls where applicable, coordinated protection schemes, and detailed operational data to support reliability engineering and compliance.

At every scale, documentation quality and design discipline remain critical. Asset-Eyes emphasizes the importance of robust documentationŌĆöpanel design drawings, wiring diagrams, and standards complianceŌĆöregardless of whether PLC, PAC, or DCS platforms are used. That advice applies with particular force to power systems, where poor documentation can translate directly into longer outages during faults or maintenance.

Bringing these threads together, you can frame the DCS vs PLC decision for UPS, inverter, and power protection projects with a few focused questions.

First, characterize your process and loop profile. If you are primarily dealing with discrete switching and a handful of straightforward analog controls, a PLC-based solution aligns with the strengths described in sources like SWIDCH, Panelmatic, and PLCTechnician. If you are coordinating many analog control loops across multiple units and buses, a DCS or at least a DCS-like integrated platform reflects the guidance from Zeroinstrument, Plant Engineering, and SWIDCH.

Second, decide how integrated your operator environment needs to be. If you intend to operate from a central control room with operators continuously monitoring the power system, the integrated database, alarm management, and visualization tools of a DCS, as described by ISA, RealPars, and Control.com, are compelling. If interaction will be occasional and local, PLC with focused HMI or light SCADA is generally sufficient.

Third, align reliability and lifecycle cost expectations with your control architecture. For very high availability requirements, where bumpless failover and distributed control are essential, DCS platforms bring built-in redundancy and reliability features highlighted by Panelmatic, Control.com, and Plant Engineering. For smaller systems or where budget constraints dominate, PLC-based solutions can offer adequate reliability at lower initial and modification cost, especially when local integrator ecosystems and widely available PLC skills are considered.

Finally, look honestly at your teamŌĆÖs skills and your cybersecurity posture. If you already operate DCS platforms elsewhere in the facility, continuing with that ecosystem for power systems may yield consistency and leverage existing training, as Control Engineering and Zeroinstrument suggest. If your organization is PLC-centric and you lack DCS experience, a carefully designed PLC-plus-SCADA architecture aligned with Control EngineeringŌĆÖs best practices may be the more sustainable choice, provided you respect the reliability and integration limits identified in Plant Engineering and RealPars.

Plant Engineering explicitly notes that PLC plus SCADA combinations can substitute for DCS in many process applications, but not all. When advanced process control, very high loop counts, and extensive operator-centric features are required, a DCS is often still the more appropriate choice. In a large power plant or complex microgrid, you can, in theory, engineer a PLC-based solution that matches many DCS capabilities. However, according to the combination of Plant Engineering, Control.com, and ISA observations, doing so usually requires substantially more custom integration work, careful management of multiple databases, and strong engineering discipline to maintain reliability and maintainability over time.

The references do not claim that DCS is inherently more reliable in all circumstances. Panelmatic, Control.com, and SWIDCH explain that DCS architectures are designed with distribution and redundancy as core principles, often eliminating single points of failure at multiple levels. RealPars, however, points out that a properly designed network of PLCs can approach the robustness of a DCS, especially when modern communication networks and redundancy techniques are applied. Conversely, a single PLC controlling an entire plant is indeed a single point of failure. In practice, reliability depends on how the architecture is designed, implemented, and maintained, not only on whether the controllers carry a PLC or DCS label.

Control Engineering advises that total cost of ownership includes engineering and commissioning, licenses, hardware, spare parts, maintenance, and upgrade cycles over 10 to 20 years. Plant Engineering adds that modification and support costs differ by ecosystem, with PLC-focused integrators and DCS vendors often having different day-rate structures and skill requirements. ISAŌĆÖs article points out that DCS tools can reduce engineering effort through pre-built templates and bulk configuration. For power systems, particularly those that will evolve over time, these factors may outweigh the initial price difference between PLC and DCS hardware.

In critical power work, you are paid not just to keep the lights on, but to keep them on predictably and safely for decades. If you treat controller selection as an integral part of your reliability strategyŌĆögrounded in the process characteristics, operator needs, lifecycle cost, and skill base described by ISA, Plant Engineering, RealPars, SWIDCH, Panelmatic, and othersŌĆöyou will choose the platform that not only runs on day one, but that your team can confidently depend on when the grid blinks and the uptime clock really starts counting.

Leave Your Comment