-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Modern industrial power systems live or die by the quality of their control layer. For most plants, that ŌĆ£brainŌĆØ is a distributed control system, surrounded by UPS systems, inverters, transfer switches, protection relays, and a mix of legacy and modern I/O. When that brain ages out, the question is no longer whether to migrate, but how to migrate and what platform strategy to pursue.

Across power-critical facilities, the plants that handle DCS migration well tend to follow the same pattern. They treat the project like brain surgery on a patient whose heart and lungs must keep running. They plan early, use platform change as a chance to reduce operational risk, and align control decisions with power reliability and safety objectives rather than just ŌĆ£refreshing old hardware.ŌĆØ

This article takes a practical look at DCS platform-change strategies, grounded in best practices from organizations such as ISA and ARC Advisory Group, and in guidance published by Schneider Electric, Rockwell Automation, Emerson, Yokogawa, and others. The focus is on what these strategies mean in a real plant with UPS-backed loads, critical inverters, and power protection equipment that cannot go dark.

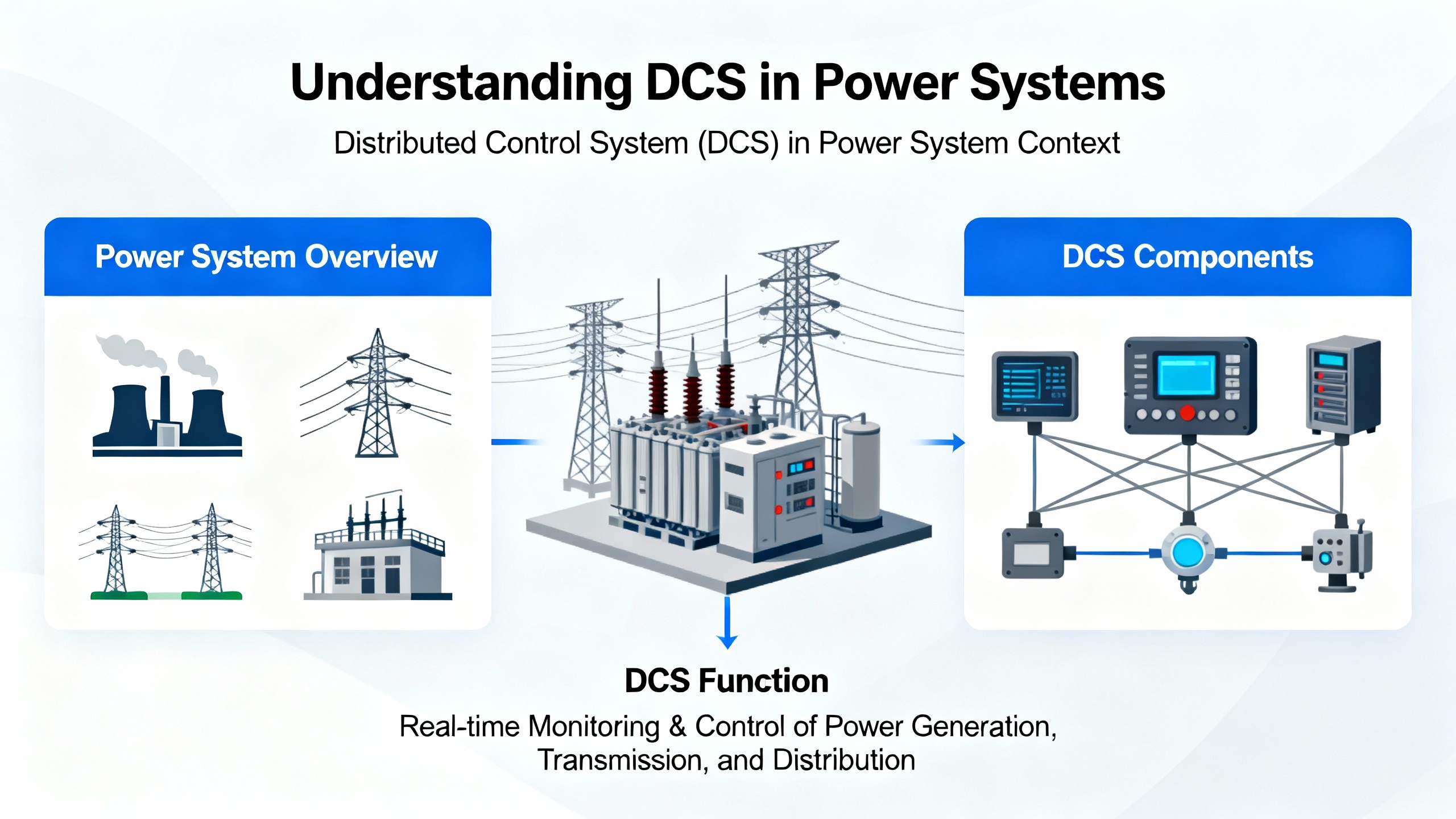

A distributed control system is the plant-wide automation backbone for process facilities. It coordinates control loops, sequences, alarms, and interlocks across boilers, turbines, switchgear, UPS systems, rectifiers, inverters, and the balance of plant.

Older DCS platforms were designed for a very different world. Hardware was robust but inflexible, HMI graphics were basic, and cybersecurity assumed an air-gapped plant network. Vendors often promised long lifecycles, but the reality is that many of those systems are now at or past end of life. ARC Advisory Group has estimated tens of billions of dollars of installed process automation systems approaching obsolescence, much of that in first- and second-generation DCS platforms.

For industrial power systems, that obsolescence shows up in specific ways. Spare parts for controller and I/O racks become rare or are sourced through risky ŌĆ£eBay and prayŌĆØ channels. Operating systems on HMI and engineering workstations fall out of support, leaving UPS-backed control rooms running on unpatched Windows versions. Engineers who know the legacy platform retire. Meanwhile, the plant is asked to integrate new power assets, such as high-efficiency inverters or battery systems, into a control system that struggles to talk to anything designed this century.

Eventually, the cost and risk of maintaining the status quo exceed the cost and risk of modernizing. The key question shifts from ŌĆ£Do we migrate?ŌĆØ to ŌĆ£How do we migrate and which platform strategy best protects our process and power integrity?ŌĆØ

Multiple independent sources converge on the same drivers for DCS migration.

First, hardware and software obsolescence. BBA Consultants point out that shortages of spare parts, original operator consoles, and supported operating systems can jeopardize production for days or weeks. Rockwell Automation and Plant Engineering emphasize that electronics lifecycles are shrinking while many DCS installations have been in place for more than twenty years. At some point, the next failed controller or comms card cannot be replaced within a reasonable outage window.

Second, knowledge and support erosion. Plant Engineering notes a shrinking pool of engineers and technicians who can support legacy platforms, while OEM training and service taper off. That knowledge risk is especially acute around power systems where misconfigured logic or misunderstood interlocks can directly affect safety and continuity of supply.

Third, cybersecurity exposure. Early DCS installations were built around an implicit air gap. Today, process control networks are increasingly connected to business systems and remote maintenance tools. Articles from ISA, InstrumentBasics, and Inside Automation highlight that many HMI and SCADA systems have gone a decade or more without security patches, making them attractive targets for modern attackers. Government guidance from NIST, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Energy, and NERC reinforces that control systems must be hardened as part of any modernization effort.

Fourth, integration and performance limitations. Legacy DCS platforms often use proprietary data structures and slow networks that cannot support modern analytics, asset management, or high-performance HMIs. Modern platforms, as described by Rockwell Automation, Emerson, and Yokogawa, provide real-time data access, advanced control algorithms, and tools for predictive maintenance and digital twins. For power systems, that translates into better visibility on breaker operations, UPS performance, fault currents, and event sequences that matter when something trips.

Finally, lost opportunity cost. Control Engineering cites research showing that operators may take roughly forty percent longer to resolve abnormal situations when using legacy HMIs compared with high-performance designs, and that typical plants lose more than five percent of capacity each year to disruptions tied to poor alarm response. Those numbers come from process plants, but the pattern is familiar to anyone who has watched operators fight cascades of nuisance alarms during a power disturbance.

Once a plant decides to modernize, the first strategic question is whether to stay with the incumbent DCS vendor or move to a new platform.

Plant Engineering and Schneider Electric both stress that either path can succeed, but each has distinct trade-offs.

A concise comparison looks like this:

| Platform choice | Main advantages | Main drawbacks |

|---|---|---|

| Stay with incumbent vendor | Easier to port control strategies and graphics; defined migration kits and paths; less training shock for operators. | Risk of locking into the same commercial and lifecycle constraints; vendors may oversell hardware; automated conversion tools may miss logic nuance. |

| Switch to a new vendor | Chance to reset standards, negotiate lifecycle and support terms, and align with preferred technology stack for power and process; may offer better advanced control or cybersecurity. | Higher engineering effort to translate strategies, retrain staff, and validate behavior; risk of underestimating integration effort with existing UPS, relays, and third-party systems. |

| Hybrid or multi-platform approach | Ability to choose best-of-breed platforms for different units (for example, one vendor for process, another for electrical SCADA); mitigates single-vendor risk. | Greater complexity in integration, lifecycle management, and skills; requires strong architecture and governance. |

Independent advisors such as ARC, ISA experts, and platform-neutral integrators repeatedly warn against relying solely on vendor ŌĆ£dog and ponyŌĆØ demos. They recommend defining clear critical-to-quality criteria first. Typical CTQs include support for advanced process control, scalability, HMI quality, proven migration paths, regional installed base, and readiness for IIoT and cybersecurity standards such as ISA/IEC 62443.

For power-focused facilities, the CTQ list should explicitly include compatibility with protective relays and power meters, native support for common protocols in electrical systems, and the ability to model and alarm on power quality and UPS status with minimal custom coding.

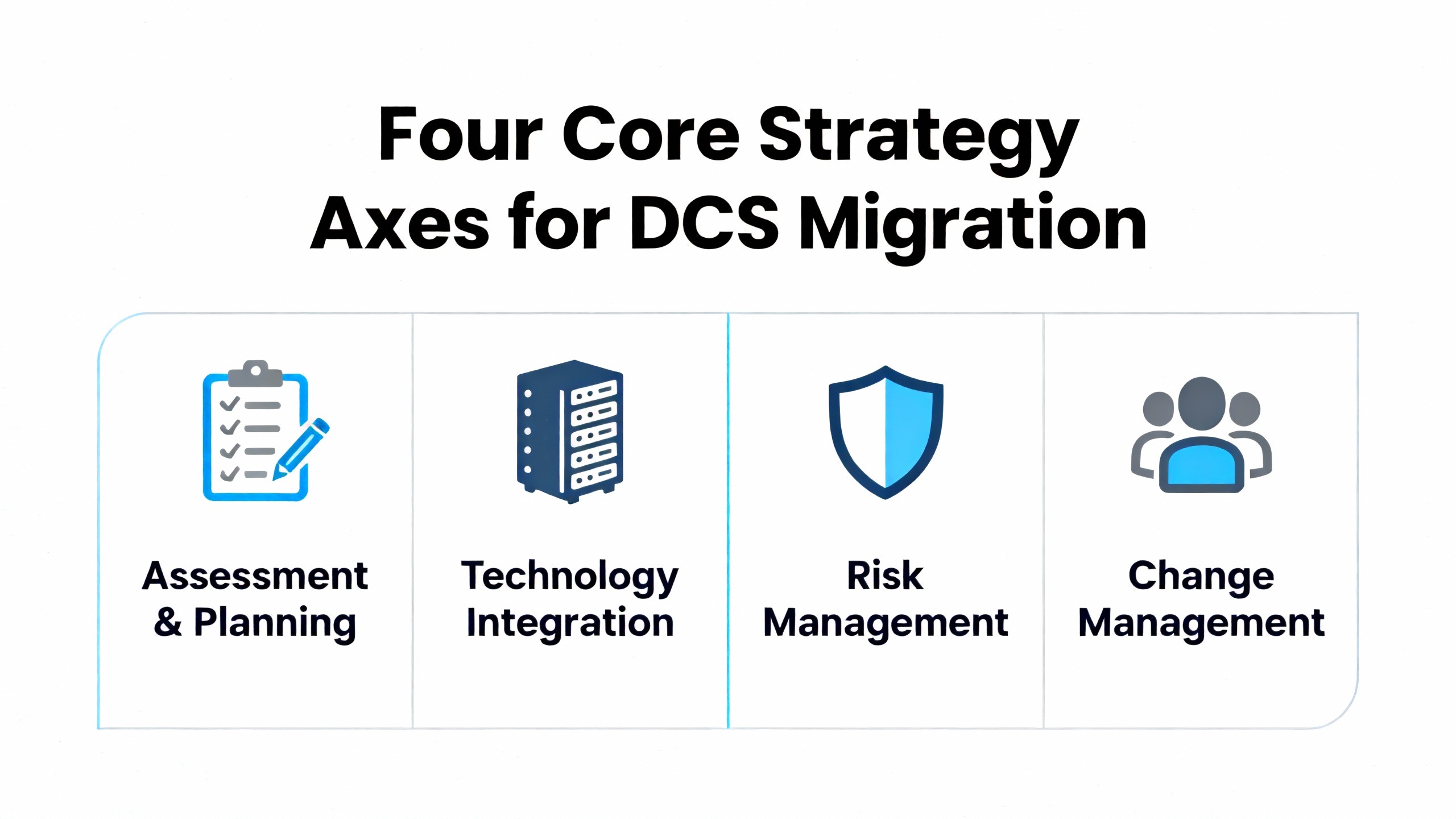

Beyond the vendor decision, several strategic axes define how the migration and platform change will unfold. Articles from IEBMedia, Plant Engineering, Emerson, and Rockwell Automation highlight four that matter most.

Replication means replacing obsolete hardware with new components while keeping functionality as close to identical as possible. In practice, replication strategies reuse control logic, alarm setpoints, and even old HMI designs. The main benefit is lower upfront engineering effort and reduced operator surprise. For power systems, replication can be attractive where interlocks are heavily certified or tied to safety cases.

The downside, as IEBMedia points out, is that you carry forward the limitations of the old system. Poor alarm handling, confusing graphics, and rigid architectures remain unchanged. You may gain more memory and processor speed, but you leave productivity and situational awareness benefits on the table.

Innovation takes the opposite view. Instead of cloning the past, it rethinks control strategies and HMIs to exploit capabilities of modern platforms. That may include automating manual switching steps, implementing model-based control for boilers or turbines, rationalizing alarms, and adding analytics that watch for degrading breaker operation or UPS battery health. IEBMedia notes that plants using innovation-focused upgrades often see better quality, less scrap, and fewer safety incidents. Control Engineering adds that properly designed high-performance HMIs measurably reduce operator response times during abnormal events.

Innovation requires more upfront engineering effort and change management, but for most facilities with finite capital, the best results come from a selective innovation approach. That means replicating what truly works and innovating where the return on investment is highest.

A rip-and-replace approach swaps the entire DCS in a single outage. Engineering may be simpler on paper, and hardware and installation costs can look lower because everything is done in one mobilization. However, downtime is concentrated into a single, long outage with elevated startup risk.

Phased migration spreads the work over several projects and outages. IEBMedia describes a common pattern where plants modernize HMIs first, then controllers, then I/O. Emerson and Rockwell Automation describe similar multi-generation coexistence strategies where old and new systems run side by side.

For a power system with limited outage opportunities, phased migration is usually the only feasible option. BBA Consultants break phased DCS migration into an initial phase focused on operational infrastructure and HMIs, followed by a phase where controllers, I/O, and control programs move over. In phase one, plants modernize Ethernet networks, data servers, and virtualization so that the new DCS has a reliable ŌĆ£nervous systemŌĆØ to ride on. Only then do they tackle the controllers and field terminations.

The trade-off is that phased migrations require more coordination and longer calendar duration. The payoff is reduced risk per step and the ability to align work with existing maintenance and turnaround schedules.

IEBMedia explains horizontal and vertical upgrade approaches with simple process examples. A horizontal approach upgrades similar equipment across the plant at once. For example, all boiler HMIs might be replaced in a single project, or all turbine controllers swapped together, regardless of which process areas they feed.

A vertical approach upgrades a complete slice of a unit. For a combined heat and power plant, that might mean upgrading the turbine control, generator excitation, switchgear I/O, and local HMIs for a single unit as one integrated package.

The choice is usually dictated by process configuration and outage constraints. Where multiple units share common utilities or UPS systems, a horizontal approach to certain layers (such as common HMIs or historian infrastructure) can make sense. Where units can be isolated for maintenance, a vertical approach supports more integrated testing of process and power behavior.

Both approaches can be combined with phased migration. Many plants, for example, start with a horizontal HMI refresh and backend virtualization, then perform vertical migrations of individual units in later outages.

Hot cutover keeps the old and new systems running in parallel and moves control loops one by one or unit by unit from the legacy DCS to the new platform. Cold cutover shuts down the legacy system completely and brings up the new system in its place with no overlap.

IEBMedia and Rockwell Automation both highlight hot cutover as the preferred choice for most plants, especially where the cost of downtime is high. With hot cutover, only a small part of the system is at risk at any given moment, and control can be switched back to the old system if something behaves unexpectedly. The price is extra hardware, additional rack space, and more complex project management, since both systems must coexist during the transition.

Cold cutover can be appropriate where the plant can afford a long outage and where the cost of duplicated infrastructure is prohibitive. However, for facilities providing around-the-clock utilities and power, such as those described in Control Engineering case studies, a cold cutover is seldom acceptable.

A useful summary of these axes is shown below.

| Strategy axis | Option | Typical advantage | Typical drawback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design philosophy | Replication | Lower engineering effort; minimal change for operators. | Carries forward old HMI, alarm, and logic limitations. |

| Innovation | Unlocks modern control, diagnostics, and cybersecurity benefits. | Higher upfront design and testing effort; more change to manage. | |

| Migration method | Rip-and-replace | Simpler engineering structure; lower visible project complexity. | Long outage; elevated startup risk. |

| Phased | Spread risk and cost; align with outages; easier learning curve. | Longer calendar duration; more interfaces to manage. | |

| Upgrade scope | Horizontal | Standardizes layers (such as HMIs) across units; economies of scale. | May require complex coordination across many process areas. |

| Vertical | Enables integrated testing of each unit; aligned with unit outages. | Less global standardization per phase. | |

| Cutover style | Hot cutover | Minimizes downtime and risk; easier rollback. | Requires extra space and hardware; more complex planning. |

| Cold cutover | Simpler hardware footprint during migration; clean cut. | Requires long outage; high operational and startup risk. |

For power-critical facilities, how the migration is staged matters as much as which DCS platform you choose. The control system cannot lose track of breakers, transformers, or UPS transfer logic simply because a new HMI came online.

BBAŌĆÖs phased approach begins with modernizing operational infrastructure and HMIs. This phase typically includes upgrading to industrial Ethernet networks, deploying new data servers, and introducing virtualization. In a power system context, that may also be when you consolidate electrical SCADA and process HMIs onto a common platform, rationalize alarm presentations for power events, and ensure UPS-backed servers are sized and configured to host virtual machines for the new DCS environment.

Virtualization is particularly important. By storing operating system images and DCS applications inside virtual machines, plants can migrate or recover those systems more easily if hardware fails or is replaced. That directly affects reliability for power system monitoring and control, because the virtual machines that host breaker, relay, or UPS graphics can be restarted on new hardware without touching the control logic in field devices.

Once the infrastructure and HMIs are in place, BBA describes a second phase focused on migrating controllers, I/O, and control programs. Here, strategies from Emerson and Rockwell Automation come into play. Migration interface modules and universal I/O cards can be used to connect new controllers to existing terminations and field wiring. Hot cutover techniques allow one control loop at a time to be transferred from the legacy DCS to the new platform while both remain live. For power systems, that might mean migrating non-critical monitoring points first, then moving into protection-related interlocks only after exhaustive simulation and staged testing.

YokogawaŌĆÖs experience with high-availability control systems underscores the reliability goals that justify this effort. Their CENTUM VP system, for example, reports ŌĆ£seven ninesŌĆØ of availability when deployed using redundant ŌĆ£pair and spareŌĆØ controller architectures. Similarly, integrated safety systems such as ProSafe-RS, certified to international functional safety standards by organizations like T├£V Rheinland, show how a modern control and safety platform can jointly reduce the probability of dangerous failures. When you replatform your DCS, the migration is often the only practical opportunity to step up to that class of availability and safety integration.

Regardless of platform or migration style, front-end loading is the most reliable way to control risk and cost. ISA, InstrumentBasics, and Rockwell Automation all stress that the most cost-effective time to influence a modernization project is in its early conceptual and planning phases. Once hardware is ordered and cutover dates are on calendars, change becomes expensive.

Control Engineering breaks FEL into three phases, each with increasingly accurate estimates. The first phase defines high-level scope and provides a rough go or no-go decision. The second phase focuses on capital planning and vendor selection, tightening estimates and identifying major risks in safety, cybersecurity, downtime, resources, network traffic, and data integrity. The third phase funds specific projects with detailed engineering and roughly ten percent accuracy.

For a power-focused plant, FEL should explicitly map how the DCS migration interacts with electrical protections, UPS autonomy, generator start sequences, and plant black-start procedures. That includes answering practical questions. During hot cutover, what keeps essential UPS loads powered if a breaker misoperation occurs? How will relay trip signals and interlocks be tested in a staging environment without compromising safety? Will the new DCS architecture segregate power and process networks in line with NERC and NIST guidance?

Power system reliability is not just about the DCS, of course. But during migration, the DCS often becomes the highest risk single point of change, because it touches so many components at once. Sound FEL planning ensures that protective relays, mechanical protections, and UPS transfer logic are treated as independent layers of defense, not as afterthoughts in a control project.

Multiple sources highlight cybersecurity as both a driver and a design criterion for DCS platform change. AFSŌĆÖs best-practices article describes how many industrial applications lack routine updates and security patches, making them prime targets for attackers. They recommend regular, high-frequency risk assessments, ideally conducted by independent experts.

Government and industry frameworks from organizations such as NIST, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Energy, and NERC provide guidance on network segmentation, monitoring, incident response, and recovery. ISA and MESA offer standards and training for secure industrial automation and control systems. Any serious DCS migration should explicitly adopt and reference these frameworks.

In practical terms, that means designing the new platform with layered defenses. Typical measures include separating corporate and control networks with firewalls, using demilitarized zones for historian and reporting servers, enforcing strong authentication and change management for control applications, and ensuring all newly deployed Windows or Linux hosts can be patched and monitored without compromising uptime.

From a power-system perspective, this is not only about protecting process data. It is about protecting breaker operations, generator dispatch, and UPS and battery management from malicious or accidental disruptions. A DCS migration that modernizes the platform but leaves unsecured remote access, flat networks, or shared passwords in place simply trades one risk for another.

Industrial power systems are unforgiving environments for experimentation. That is why so many of the case studies and best-practice articles emphasize the role of experienced partners.

Plant Engineering and Inside Automation repeatedly compare DCS migration to brain surgery and argue that domain and business expertise are as important as platform knowledge. Cross CompanyŌĆÖs work migrating DTE Calvert City from APACS to a modern DCS shows the value of integrators who have executed similar transitions, can navigate vendor-specific pitfalls, and will be present on-site during critical cutovers.

Malisko and other platform-neutral integrators position their role as ŌĆ£listen, then design.ŌĆØ They stress early requirements definition, close collaboration with plant teams, and the use of migration as a strategic initiative rather than a simple hardware swap. Third-party partners also provide an independent view of vendor proposals, helping clients avoid overbuying hardware or underestimating engineering complexity.

For facilities with limited in-house capacity, outcome-based support models can be attractive. Plant Engineering describes arrangements where vendors or integrators take on part of the lifecycle responsibility under fixed-cost contracts tied to performance outcomes, including preventive maintenance and continuous monitoring. Regardless of model, the common principle is to ensure that whoever designs and implements the migration will also help support it through the early years of operation.

Turning all of this guidance into a decision framework is less about inventing new theory and more about disciplined application.

A first step is to clarify business drivers in the context of your power system. That means quantifying the cost of unplanned outages, near misses, and maintenance overtime tied to the current control platform. It also means documenting which future capabilities matter most, such as advanced power quality analytics, tighter generator and UPS coordination, or better remote operations.

Next, map the technical and operational scope. Create a complete inventory of controllers, I/O, HMIs, networks, UPS-backed servers, relay panels, and key interlocks. Document dependencies among process units and electrical systems so that potential cutover sequences can be compared objectively. Lessons from data center migration literature are instructive here: do not underestimate the value of a thorough asset inventory and dependency map.

With that foundation, select a platform strategy tailored to different parts of the plant. In some areas, a replication-heavy, stay-with-the-vendor approach might be appropriate, particularly where safety cases are tightly bound to existing code. In others, such as new combined heat and power units or microgrid controllers, an innovation-focused migration to a different vendor may offer greater long-term value.

Design the cutover strategy around real outage opportunities and power-system constraints. For units that see turnaround intervals of several years, a hot cutover with multi-generation coexistence may be the only realistic choice. For non-critical systems or new builds, a cold cutover or even greenfield deployment may be acceptable. Align each strategy with the FEL roadmap to ensure capital and resource requirements are realistic year by year.

Finally, invest in testing and lifecycle planning. Multiple sources emphasize the importance of factory and site acceptance tests, simulation-based operator training, and side-by-side HMI running against simulated processes before going live. Once the new platform is in operation, treat it as the next starting point in an intentional lifecycle, not as a ŌĆ£set and forgetŌĆØ asset. That means continuous risk assessment, patching, and periodic architecture reviews to ensure the DCS continues to support both process performance and power reliability.

The DCS does not replace protective relays or UPS logic, but it orchestrates how those devices are monitored, alarmed, and often commanded. A modern platform with better integration to protection relays, metering, and UPS controllers can provide more accurate alarms, trend analysis, and interlocks. During migration, it is critical to preserve existing protections as independent layers while improving how the DCS visualizes and supervises them.

For most power-critical sites, phased migration combined with hot cutover is the only practical path, because long outages are not acceptable. However, there are exceptions, such as new units added to an existing site or plants undergoing major rebuilds where a more aggressive approach is feasible. The real question is how much risk and downtime the business can tolerate and what mitigation measures are available.

The earlier the better. FEL guidance from ISA and Control Engineering shows that decisions made in the earliest planning phases have the biggest influence on cost and risk. In practice, that means involving power engineers and protection specialists from the first conceptual discussions so that relay coordination, UPS autonomy, and black-start procedures are reflected in architecture, platform selection, and cutover planning.

A DCS migration is one of the rare projects that can reshape both process control and power-system reliability for a generation. Treated as a strategic platform change, grounded in sound FEL planning and informed by proven migration strategies, it becomes less like emergency surgery and more like a carefully planned upgrade of the plantŌĆÖs nervous system. For operators responsible for keeping critical loads powered and protected, that difference is measured in fewer midnight calls, fewer near misses, and a control system that is finally aligned with the realities of modern power and process operations.

Leave Your Comment