-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Steel manufacturing has always pushed automation to its limits. High temperatures, abrasive dust, heavy mechanical loads, and continuous production targets leave little room for control system mistakes. In that environment, a Distributed Control System (DCS) is not just another automation layer; it becomes the orchestration engine that aligns melting, casting, rolling, utilities, and power systems into one coherent operation.

From the perspective of a power systems specialist focused on reliability, I see three questions repeatedly coming from steel plant teams. Do we really need an integrated DCS solution instead of just more PLCs and local panels. How do we modernize legacy controls without disrupting production. And how do we protect that DCS from unstable power, harsh conditions, and future demands for energy efficiency and AI. The answers are emerging clearly in the experience of global mills and integrators, and they are strongly supported by the technical literature.

This article walks through those questions using evidence and case studies from vendors, integrators, and research bodies, and translates them into practical guidance for iron and steel plants that want integrated, resilient control.

Steelmaking is a chain of tightly coupled processes. Scrap or ore is melted, refined, cast, rolled, heat treated, surface treated, and finished. Each major area often had its own standalone control system: a PLC on the continuous caster, a separate system on the reheating furnace, islands of SCADA on utilities. According to integrated control system work summarized by EOXS, this fragmentation creates inefficiencies, error-prone handoffs, and higher operating costs, especially when processes like melting, casting, and rolling are tightly interdependent.

An Integrated Control System combines DCS, PLC, and SCADA elements into one coordinated architecture. EOXS describes ICS as a hardwareŌĆōsoftware network that monitors, controls, and optimizes operations across the mill. In practice, this means a DCS providing plant-wide process control, PLCs handling machine-level logic for equipment such as conveyors or furnaces, and SCADA and higher-level tools aggregating data for visualization and analysis.

DCS platforms are particularly well aligned to steel because they are designed for large, continuous or batch processes with many control loops and I/O points. Both Dadao Energy and Plant Automation Technology emphasize that a DCS distributes autonomous controllers around the plant, connects them with high-speed networks, and brings everything together in a central operator environment. This distribution helps reliability, because a failure in one controller does not take down the entire plant, and central supervision gives operations and maintenance a single pane of glass to see what the process is doing.

In metals and steel specifically, ABBŌĆÖs case study on Jindal Stainless illustrates what fully integrated automation can achieve. Jindal implemented a Direct Reduction Annealing and Pickling ŌĆ£Combo LineŌĆØ designed to process both hot- and cold-rolled stainless coils. ABB supplied an integrated solution based on its 800xA platform, with dedicated controllers for process and safety, coordinated low- and medium-voltage drives, and advanced models for the inline tandem mills. The solution had to synchronize a complex series of units including a multi-stand tandem mill, degreasing, furnace, pickling, and a skin pass mill. Within a few months of commissioning, Jindal was producing a new stainless surface finish tailored for that line, with reduced downtime and maintenance costs thanks to advanced diagnostics and data analytics.

EOXS reports similar gains at ArcelorMittalŌĆÖs Ghent plant, where a DCS upgrade delivered around 15 percent higher productivity and roughly 20 percent lower energy consumption. Those numbers align with Dadao EnergyŌĆÖs observation that modern DCS systems, when properly leveraged, can cut energy use by up to about one fifth compared with older controls, mainly through tighter process regulation and energy monitoring.

The evidence from these sources converges on the same conclusion. For complex, continuous steelmaking operations, an integrated DCS-centric control architecture is now a core competitiveness tool, not a luxury.

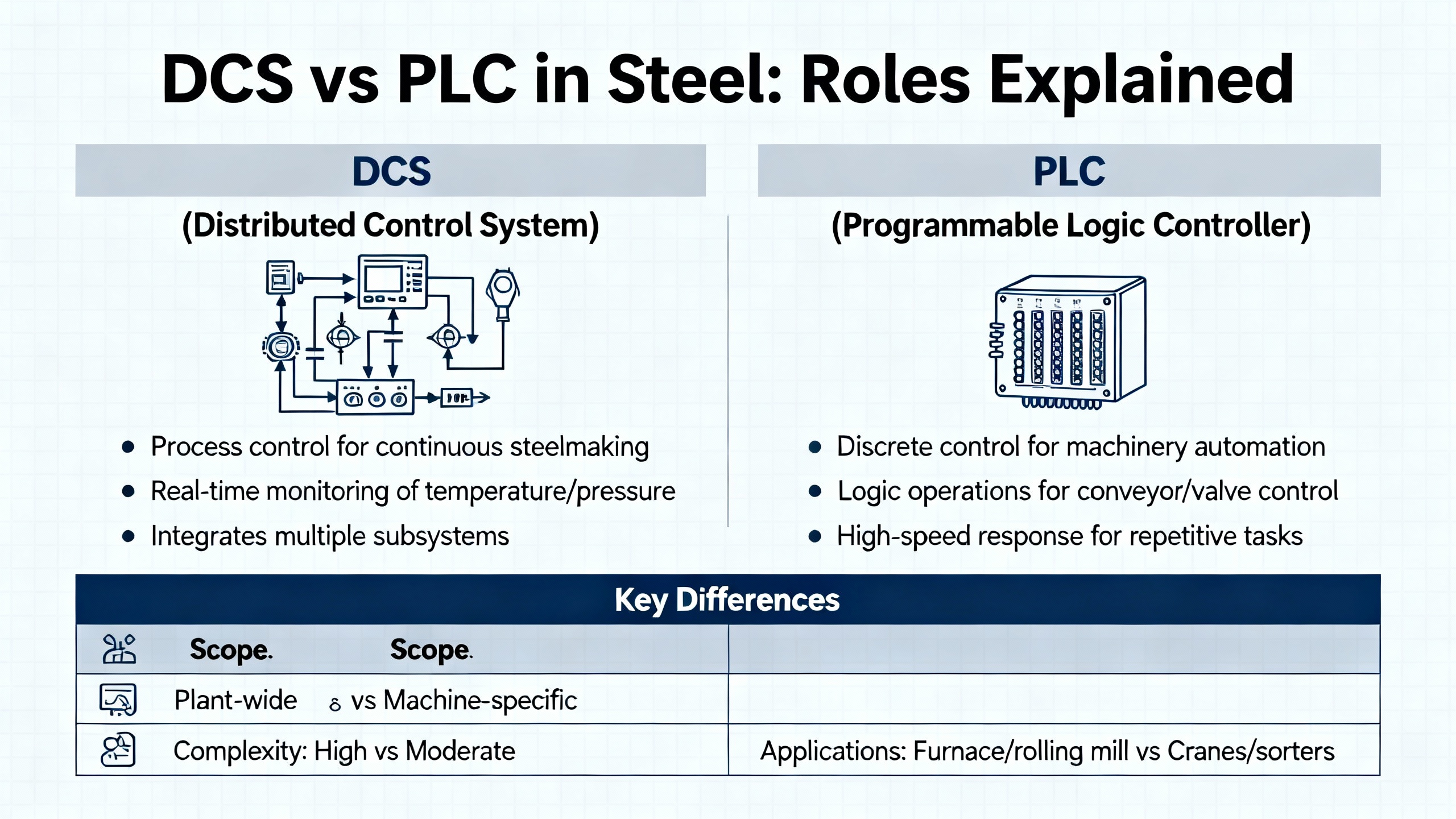

One of the first decisions plant teams wrestle with is whether to standardize on more PLC-based systems or invest in a DCS. The right answer in a steel plant is rarely eitherŌĆōor; it is about roles and boundaries.

Plant Automation Technology and Dadao Energy draw a consistent distinction. A DCS is process-centric. It is optimized to run many continuous control loops, coordinate sequences across units, and provide advanced regulatory control and analytics. A PLC is device-centric. It excels at fast, discrete control for machinery such as shears, transfer cars, and material handling.

In steel plants, that typically leads to a pattern where the DCS supervises the major process areas and utilities, while PLCs manage the local equipment details. For example, a caster mold level system or a hot strip millŌĆÖs coiler might be built on PLC logic for very fast response, but their setpoints, recipes, and interlocks tie back into the DCS. The DCS then supervises the broader mass and energy balance, quality targets, and safety envelopes.

A simple way to visualize this division of labor is to compare some prominent attributes.

| Attribute | DCS in steel plants | PLC in steel plants |

|---|---|---|

| Primary focus | Continuous and batch process control across units | Fast, discrete machine and equipment control |

| Scale of I/O | Many thousands of points across the mill and utilities | Typically up to a few thousand per machine or area |

| Operator interface | Integrated, plant-wide HMI with trends, alarms, and histories | Local panels or HMIs tied to specific machines |

| Redundancy and availability | Deep redundancy at controllers, networks, and often power inputs | Limited redundancy unless specifically engineered |

| Engineering environment | Single integrated database for logic, graphics, and reports | Separate environments per PLC and HMI vendor |

| Best-fit applications | Blast furnaces, BOF/EOF, secondary metallurgy, casters, utilities | Shears, manipulators, coil handling, individual drives or subskids |

The key in a steel plant is to avoid building what effectively becomes a DCS-like system out of uncoordinated PLCs and HMIs, which Plant Automation Technology warns can erode organization and consistency. A DCS offers the backbone for advanced regulatory control, alarm management, and lifecycle support that would be expensive to recreate from scratch using PLCs alone.

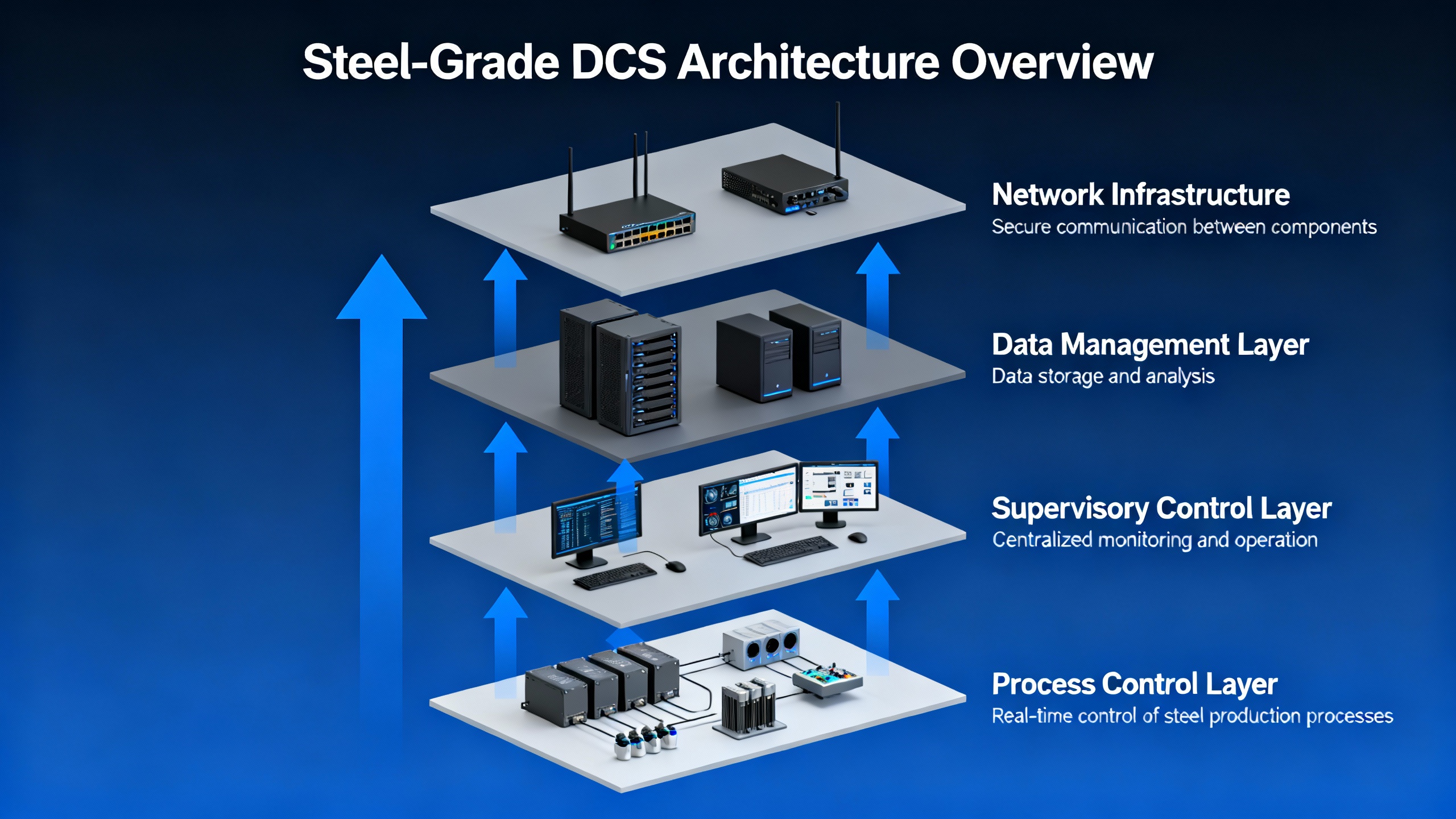

In the metals context, a DCS is not just a box of controllers. It is a hierarchical architecture that spans from field devices to scheduling systems.

Dadao Energy and Plant Automation Technology describe a typical structure that fits well in steel plants. At the base level are field devices such as thermocouples, flowmeters, level transmitters, drives, and valves. Those connect to I/O modules distributed throughout the plant, which in turn connect to process controllers that execute control strategies. Above that, operator and engineering stations provide visualization, alarm management, and configuration. At higher levels, the DCS interfaces with production management, historians, and even enterprise scheduling.

Technically, these systems now rely on high-speed Ethernet or fiber networks, using common protocols such as Modbus, Profibus, or Ethernet/IP, with millisecond-level network latency. Dadao Energy notes that well-designed DCS platforms can achieve uptime levels above 99.99 percent through extensive redundancy and fail-safes. That level of availability corresponds to less than an hour of unplanned downtime per year if the system is fully redundant and properly maintained.

DCS systems in steel also integrate advanced historians, alarm systems, and analytics. That is what allowed ABB to deploy a digital twin of the Jindal Stainless DRAP line for in-house testing before commissioning. By simulating sequences and interactions among the tandem cold mill, furnace, pickling, and skin pass units in a virtual environment, the team could debug control logic and synchronization without risking the physical line. Once the real line started up, the DCSŌĆÖs historical data and diagnostics then supported continuous optimization and early detection of issues that would otherwise become unplanned stoppages.

A smaller-scale but still instructive example comes from American SpiralWeld Pipe in the United States, described by Control Engineering. At that plant, SCADA and MES systems were deployed to monitor production of large spiral-welded pipes, some up to about 50 ft long and 12 ft in diameter. Data from thousands of tags across multiple devices feeds into a central control room equipped with large industrial displays. Operators and managers use that information to track overall equipment effectiveness, downtime reasons, and resource efficiency in real time. Although that case focuses heavily on SCADA and MES, the underlying pattern is the same as in a DCS-centric steel plant: integrated, standardized data and control logic are prerequisites for meaningful analysis and improvement.

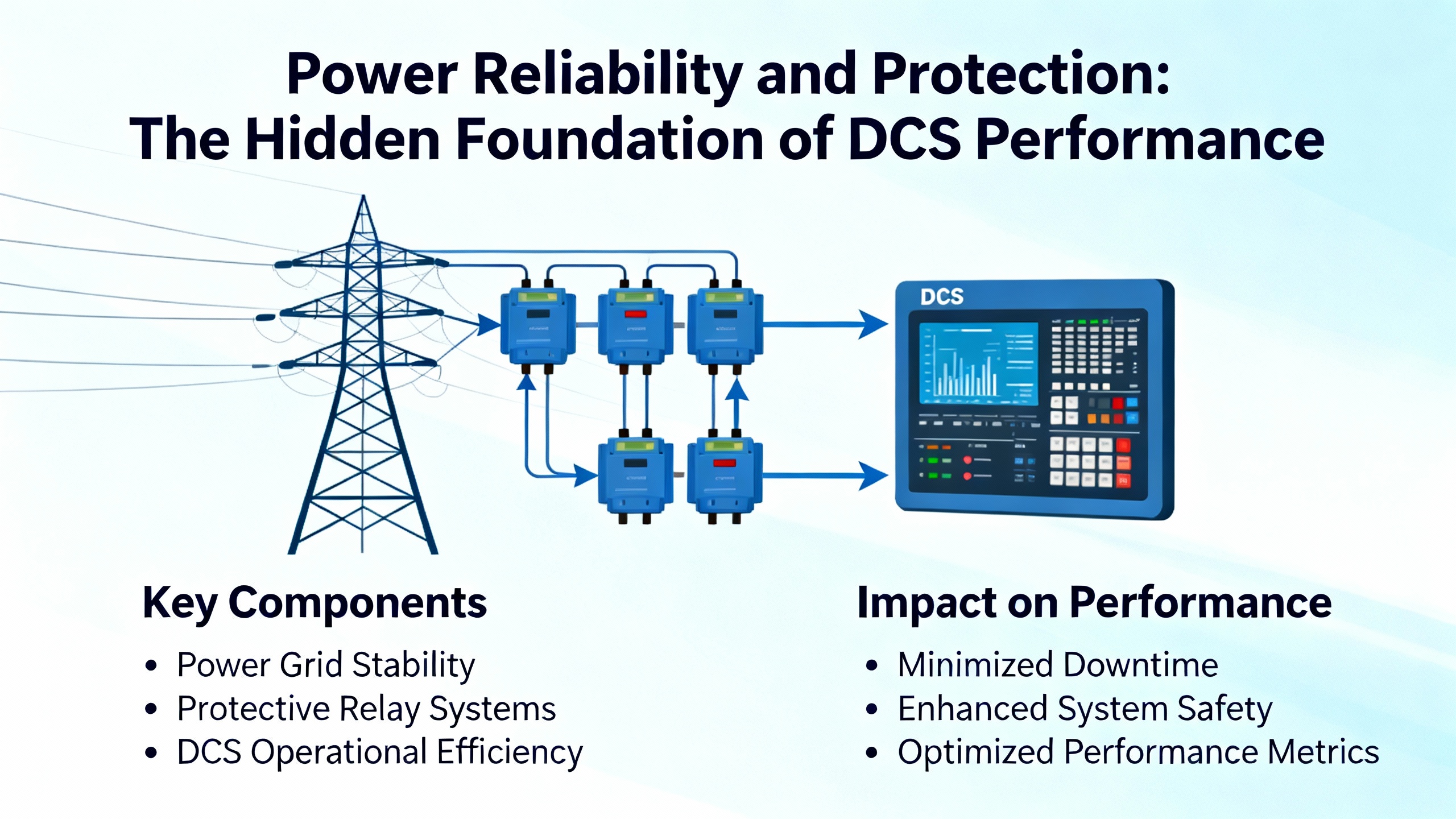

In heavy industry, most DCS failures that operations see look like ŌĆ£automation problems,ŌĆØ but a surprising number trace back to power quality and environmental stress. Jiwei AutomationŌĆÖs guidance on DCS fault diagnosis in heavy industries, including steel, makes this point clearly. Common hardware faults such as controller failures, I/O module issues, and communication dropouts frequently originate from unstable power supplies or external disturbances, not from the core automation hardware itself.

Jiwei highlights unstable powerŌĆövoltage fluctuations, brief interruptions, or sagging suppliesŌĆöas a major external factor that can degrade DCS performance or trigger shutdowns. In a steel plant, those disturbances can originate from large motor starts, arc furnace flicker, or switching events on the medium-voltage network. When the control power feeding DCS cabinets, I/O racks, and network switches is not adequately protected, even a short disturbance can cause a controller reboot or a communication fault, sometimes long after the plant has invested heavily in redundant automation hardware.

The recommended mitigations are exactly the types of measures a power systems specialist cares about. Jiwei advises stabilizing and upgrading power systems that feed DCS equipment, including the use of voltage regulators and uninterruptible power supplies. Properly designed UPS systems can ride through short disturbances and provide orderly shutdown or redundancy for longer events. When combined with good segregation between clean control power and noisy process power, this is often the cheapest ŌĆ£automation upgradeŌĆØ a plant can implement.

Environmental conditions matter just as much. Jiwei notes that extreme temperature, high humidity, and electromagnetic interference all contribute to DCS instability and hardware faults. In steel plants, cabinets located near hot mill stands, cooling beds, or furnace floors often face ambient temperatures and dust levels that exceed the ratings of delicate electronics. Maintaining climate-controlled control rooms, sealing and filtering enclosures, and applying proper shielding and grounding practices can dramatically improve long-term reliability.

Hargrove Controls & AutomationŌĆÖs steel project provides a practical illustration from a different angle. In that case, the primary driver for a control upgrade was not power quality but obsolescence. The clientŌĆÖs control hardware and software were no longer supported by the vendor, and spare parts were scarce. This led to repeated equipment downtime and extended outages whenever a failure occurred. Hargrove migrated legacy DeviceNet and ControlNet networks on a critical vacuum tank degasser to Ethernet/IP, upgraded drives and soft starters, modernized HMIs on the continuous caster, and virtualized the automation servers. After the upgrade, the plant had a more flexible and maintainable platform, with renewed OEM support and lower risk from unplanned downtime.

From a reliability standpoint, both themes converge. Robust DCS solutions in steel need both modern, supportable automation platforms and solid electrical and environmental foundations. It is not sufficient to buy a high-end DCS if it runs on unstable power, in overheated or unprotected cabinets, or on networks whose switches and cables cannot withstand the mill environment.

Many steel plants today are running on a patchwork of old DCS systems, outdated PLCs, and aging HMIs. Vendors have ended support, licenses are frozen, and spares are scavenged from decommissioned lines. Yet shutting the plant down for a full rip-and-replace project is not an option. The question is how to modernize in a controlled, staged manner.

The Hargrove steel project hints at a realistic path. The scope focused on upgrading legacy control systems for critical units and utilities, rather than everything at once. For the vacuum tank degasser, the team migrated from older industrial networks like DeviceNet and ControlNet to Ethernet/IP, which better supports modern drives, diagnostics, and integration. Drives and soft starters serving that unit were upgraded to improve reliability and maintainability. On the continuous caster, a legacy Siemens WinCC application was migrated to the latest WinCC platform, consolidating on a current HMI and SCADA foundation. Across utilities, including water treatment, the plantŌĆÖs Wonderware installation was upgraded from a 2017 version to a more recent release, aligning with modern software standards.

Crucially, all relevant automation and control assets were virtualized. Instead of relying on multiple generations of physical servers and workstations, the plant now runs its control applications on a virtual environment that simplifies backups, recovery, and future upgrades. This step makes it far easier to test new software, roll back in case of issues, and extend the system as processes change.

EOXSŌĆÖs integrated control guidance reinforces that such migration should follow a staged approach. A mill needs to start with a thorough assessment of needs and objectives, identifying where obsolescence, downtime, and quality losses hurt most. It then selects a scalable, compatible control platform that will work with existing equipment and desired future upgrades. Implementation typically proceeds area by area. Engineering teams design the integration using standard libraries and templates, roll out hardware and software with careful cutover planning, perform intensive testing and validation, and then train operators and maintenance staff on the new HMIs, alarms, and workflows. After the initial upgrade, the plant continues to refine control strategies, alarm configurations, and data analytics in a continuous improvement loop.

ABBŌĆÖs work at Jindal Stainless adds another powerful tactic to the modernization playbook: digital twins. By building a virtual model of the DRAP line tied into the same control system logic, ABBŌĆÖs team could simulate complex sequences and coordination challenges before touching the real equipment. That dramatically reduces commissioning risk and time, especially when integrating advanced features such as automatic roll change devices and micro tracking for section setpoint handling.

Collectively, these experiences suggest that steel plants should treat DCS modernization as a rolling program rather than a one-off project. Start where risk and business value are highest, integrate carefully with power and network upgrades, and use virtualization and simulation to derisk each step.

Once a DCS is in place, the difference between a high-performing system and a constant source of frustration lies in daily operation and maintenance practices. Jiwei AutomationŌĆÖs detailed guidance on DCS fault diagnosis and maintenance in heavy industries is particularly relevant here.

Jiwei recommends beginning any fault investigation with symptom analysis. That means treating operator reports systematically: sluggish control responses, frozen screens, frequent alarms, or nonresponsive subsystems all provide clues. From there, technicians perform on-site hardware inspection, using tools such as multimeters and oscilloscopes to verify power quality, signal integrity, and wiring.

System log analysis is the next pillar. DCS platforms record error codes, communication interruptions, and configuration events in logs. Reviewing those logs can pinpoint whether the root cause lies in power issues, network congestion, misconfigured parameters, or software bugs. Where hardware is suspected, Jiwei recommends module replacement tests, temporarily swapping suspect controllers or I/O modules with known-good units to see whether the problem follows the hardware.

Communication link testing is essential in steel plants where long cable runs, high electromagnetic fields, and mechanical damage are common. Network diagnostic tools that measure connectivity, latency, and packet loss help identify failing switches, damaged fibers, or saturated network segments. When problems are found, Jiwei advises replacing malfunctioning network components and strengthening redundancy to improve fault tolerance.

On the software side, Jiwei points to common issues such as programming errors, misconfigured I/O, and database faults. Best practice is to debug and correct control logic offline when possible, restore known-good program backups when necessary, and validate configuration parameters against proper documentation. Database recovery tools can protect historical data and configuration records if corruption occurs.

Preventive maintenance is arguably more important than troubleshooting. Jiwei stresses regular inspection of hardware, software, and communication lines; scheduled backups of control programs and databases; and clear operating procedures and emergency plans. Training operators to recognize early signs of DCS trouble and respond appropriately is just as important as training specialists. That training should cover fault recognition, use of diagnostic tools, and safe fallback procedures in case of system failures.

ZeroInstrumentŌĆÖs discussion of DCS configuration best practices, although based on general engineering knowledge rather than a specific article, aligns well with these maintenance principles. It emphasizes that consistent tag naming, standardized control and HMI templates, and disciplined change management make systems easier to maintain and troubleshoot. Simulation environments and digital twins, as seen in ABBŌĆÖs Jindal project, further reduce risk by allowing configuration changes to be tested before deployment.

SCADA and MES deployments like the American SpiralWeld Pipe project reinforce the value of good data and visualization for operations. At ASWP, real-time monitoring of OEE, shift performance, downtime reasons, and rework history gave both operators and managers a much clearer picture of where to act. When the underlying DCS or SCADA data is consistent and well-structured, these tools can transform daily decision-making from intuition-driven to evidence-driven.

For a steel mill, the message is clear. A DCS is not a ŌĆ£set-and-forgetŌĆØ system. It needs structured fault diagnosis routines, rigorous preventive maintenance, and ongoing training to deliver the availability and performance implied by its design metrics.

Beyond immediate reliability and throughput, modern DCS solutions are becoming the backbone of energy and environmental performance in steel plants. The steel industry is energy intensive, consuming more than about a tenth of national energy in some countries according to research published in the journal Processes, and faces pressure to reduce emissions and improve energy efficiency.

That same research highlights the value of integrating steel process gasesŌĆöconverter, blast furnace, and coke oven gasesŌĆöinto thermoelectric systems that couple industrial gas, steam, and electricity. When those byproduct gases are purified and used effectively, they can significantly cut net energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. For large steel plants with continuous gas output, the recommendation is to combine gas utilization with very large supercritical steam turbines and robust waste-heat recovery, along with gas purification and tail-gas desulfurization and denitrification.

Smaller and medium-sized plants, whose gas output is smaller and more intermittent, are better served by pressurized internal-combustion gas generators rather than large turbines. Processes describes practical implementations, such as plants using multiple engines for self-power generation and achieving notable production cost reductions. In all of these cases, automated and intelligent control is essential, especially for tail-gas treatment systems operating under highly acidic conditions. The article notes that without robust automation, high failure rates in valves and sensors force manual operations, degrading environmental performance and undermining investment in environmental technology.

Modern DCS platforms provide the infrastructure needed to implement these complex energy systems. They can coordinate gas flows, boiler and turbine operations, and tail-gas treatment in real time, backed by high-speed I/O and redundant controllers. When combined with historians and analytics, they enable plants to tune control strategies for both energy efficiency and environmental compliance.

On top of that, AI-based optimization is emerging as a significant opportunity. Griffin Open Systems describes reheat furnaces as a natural focus for AI in the steel industry. These furnaces consume large amounts of energy and directly impact product quality. Common challenges include inefficient energy use, control systems that are hard to tune, and high reject rates when slabs exit the furnace outside acceptable temperature bands. Griffin characterizes AI in this context as a layer of control system optimizers that compute optimal temperature setpoints, improving energy efficiency, control performance, and product acceptance rates.

Successful AI deployment depends on integration and transparency. Both GriffinŌĆÖs recommendations and the Processes articleŌĆÖs discussion of advanced control tools emphasize that AI platforms should integrate cleanly with existing DCS and data infrastructure and present information in ways that operators understand. No-code or low-code interfaces help control engineers and operators model and test optimizations without relying on rare data science skills. Open architectures and transparent models are preferred over opaque ŌĆ£black boxŌĆØ systems, because industrial deployment demands traceability and trust.

Processes also introduces advanced AI control tools such as multivariable model predictive control based on deep learning, fuzzyŌĆōneural adaptive control, and deep-learning soft sensors. In steel smelting furnaces, where high temperatures, dust, and large spatial gradients make direct measurement difficult, soft sensing that fuses multiple raw data sources is essential for estimating furnace state in real time. Those estimates feed into optimization and control algorithms that can maintain stability and quality without adding large amounts of physical instrumentation.

DCS platforms are central to all of this. They host or connect to the soft sensors, provide the real-time data streams, and execute the optimized control strategies. Vendors like ABB are already coupling digital twins with control systems, as at Jindal Stainless, to test and refine advanced logic before deployment. Dadao Energy notes that data historians and analytics embedded in DCS architectures pave the way for predictive analysis and machine-learning-based optimization.

Taken together, these sources show that a robust DCS is not only a tool for reliability and safety; it is increasingly the foundation for energy optimization, AI, and the transition to greener steel.

Given this landscape, plant leaders and engineers still need a practical way to decide what to do next. While each mill is unique, the combined guidance from Dadao Energy, Plant Automation Technology, EOXS, Hargrove, Jiwei, Griffin, Processes, ABB, and Control Engineering suggests a few clear lines of reasoning.

First, consider your scale and process type. If you operate a large, continuous or batch-oriented integrated steel plant, or even a mini-mill with complex process flows, and you care about plant-wide optimization, safety, and analytics, DCS-centric architectures are strongly recommended by both Dadao Energy and Plant Automation Technology. If your operations are primarily discrete, with relatively simple machine-level processes and low integration needs, PLC-based solutions may still be sufficient in that area.

Second, assess your risk from obsolescence and unplanned downtime. If your control systems are out of support, spare parts are scarce, or downtime events are increasing, your situation resembles the Hargrove steel client. In that case, a structured modernization program focusing on critical assets, standardized platforms, and virtualization should move up your priority list.

Third, examine your power and environmental conditions around automation assets. JiweiŌĆÖs analysis of power quality and environmental factors as root causes of DCS failures should serve as a warning. If DCS cabinets currently draw power from noisy process buses without UPS protection, or sit in areas exposed to heat, humidity, and electromagnetic interference, investing in power conditioning, UPS-backed control power, and improved cabinet environments may yield outsized benefits relative to cost.

Fourth, think about your data and optimization ambitions. If you have initiatives around energy efficiency, AI, or green steel, the advanced AI control strategies discussed in Processes and GriffinŌĆÖs work on reheat furnaces make it clear that a solid DCS and data infrastructure is a prerequisite. You cannot reliably optimize what you cannot measure or control consistently.

Finally, factor in people and procedures. EOXS and Jiwei both stress training and change management. Any DCS or ICS upgrade must be accompanied by operator and maintenance training, clear procedures, and ongoing support. Without that, even the best technology will underperform.

Question: When is a full DCS justified instead of just adding more PLCs.

Answer: Sources such as Dadao Energy and Plant Automation Technology suggest that a DCS is justified when you have large, continuous or batch processes with many control loops, need plant-wide optimization and safety, and expect to integrate analytics, historians, and advanced control. Steelmaking fits that profile. PLCs remain excellent for machine-level tasks, but when you find yourself stitching together many PLCs and HMIs to mimic plant-wide control, the overhead and risks typically exceed the cost of deploying a proper DCS backbone.

Question: What are the most critical power-related actions to protect a DCS in a steel mill.

Answer: Jiwei AutomationŌĆÖs fault analysis highlights three especially important measures. Stabilize and condition the power feeding DCS controllers, I/O, and networks with voltage regulators and UPS systems. Ensure proper grounding and shielding to reduce electromagnetic interference from heavy equipment. Maintain suitable temperature and humidity in control rooms and enclosures. Combined with DCS-level redundancy, these actions significantly reduce nuisance trips and hardware failures driven by the harsh steel environment.

Question: How can we prepare for AI and advanced optimization in our steel plant.

Answer: Research from Processes and recommendations from Griffin Open Systems both point to the same prerequisites. Build a robust DCS and data foundation with consistent tag naming, reliable historians, and integrated control across process units. Prioritize transparency and open architectures so that AI tools can integrate cleanly and operators can understand their recommendations. Start with high-impact, energy-intensive units such as reheat furnaces or gasŌĆōsteamŌĆōpower systems, where AI-driven setpoint optimization can directly reduce fuel use and improve quality, provided the underlying control system is stable and well-instrumented.

Steel plants are unforgiving environments. In that context, a well-architected DCS paired with reliable power, disciplined maintenance, and thoughtful integration of analytics is one of the few levers that can simultaneously improve safety, uptime, quality, and energy performance. Thinking like a power system and reliability engineer about your control systemŌĆötreating it as critical infrastructure, not just automation hardwareŌĆöis often what separates mills that merely keep running from those that run smarter and more profitably.

Leave Your Comment