-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

HumanŌĆōmachine interfaces are effectively the nervous system of a modern control room. When an Allen Bradley PanelView goes blank, garbled, or refuses to talk to the PLC, operators suddenly lose their eyes and hands on the process. From a power-system reliability perspective, that is not just an annoyance; it is a direct hit to uptime, safety, and every asset tied to that machine, from inverters and drives to UPS-backed control cabinets.

This guide walks through how to diagnose and repair Allen Bradley PanelView display problems in a way that respects both the electronics and the power infrastructure behind them. The focus is practical: what to check first on the plant floor, when to suspect power quality, when a screen swap is enough, and when it is time to call a professional repair house or replace the unit.

Allen Bradley PanelView terminals are HMI panels that display process data and let operators control PLC-based systems. They run application files, often in the .mer format created in tools such as FactoryTalk View Machine Edition, and they sit at the center of any serious automation cell.

From multiple field reports and repair-center case studies, most HMI failures fall into a few repeatable categories. Articles from automation repair specialists and HMI-focused service providers consistently describe four broad groups: screen and backlight failures, touchscreen problems, communication and tag errors, and deeper software or hardware faults.

Screen issues show up as dim, flickering, garbled, or completely black displays. Over time, backlights and LCDs age and fail, which is exactly what Monitech describes for PanelView Plus 600 units, where the cure is usually a replacement LCD or complete screen assembly rather than a new terminal. Touch problems, highlighted by Synchronics, Xinje, and several other sources, include unresponsive zones, ghost touches, and miscalibration, often caused by worn resistive layers, contamination, or damaged overlays.

Communication and software faults are just as common as physical problems. A troubleshooting guide from TCI Supply cataloging Allen Bradley PanelView error codes shows that many alarms trace back to missing displays in the project, tag misconfigurations, offline controllers, path errors, or runtime files that will not launch. Other issues, such as memory or storage errors, licensing faults, or missing ActiveX controls, are software and configuration problems that look like a ŌĆ£deadŌĆØ HMI to an operator even though the hardware is intact.

Underneath all of this is the power system. Power supply issues are repeatedly flagged as a primary root cause of HMI failures. Industrial Automation Co. notes that more than a quarter of HMIs they receive as ŌĆ£deadŌĆØ turn out to have simple power problems rather than internal damage. IVS Incorporated and the Allen BradleyŌĆōfocused troubleshooting article from Apter also emphasize that unstable voltage, surges, and abrupt power loss are behind many apparently random display failures. For a power-systems specialist, that is the first place to look.

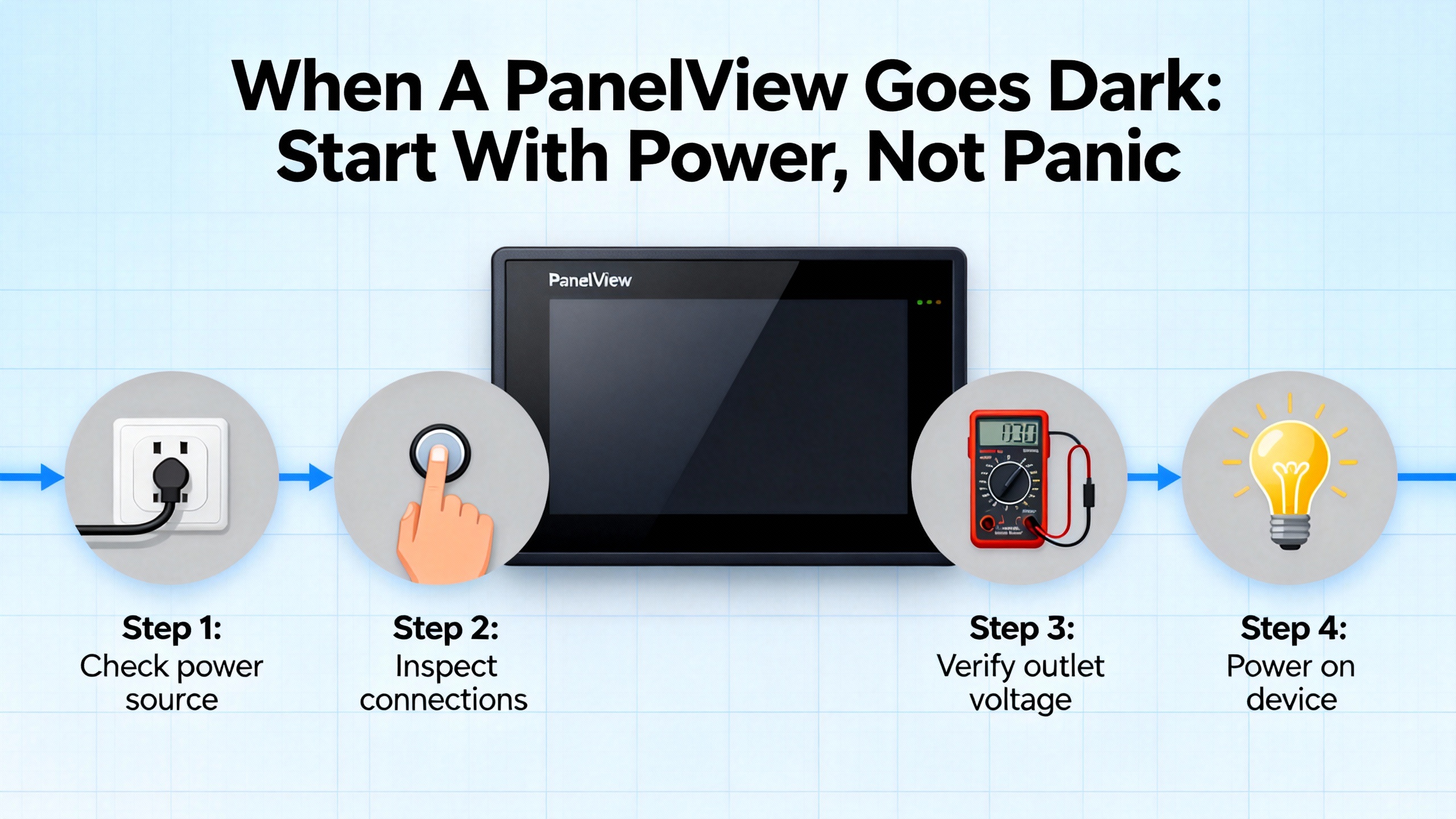

When an Allen Bradley HMI will not turn on, shows a completely blank screen, or looks dead after a power event, there is a structured way to approach it that avoids unnecessary replacements.

In the field, I start with the power chain from the upstream breaker or UPS all the way to the HMI terminals. Industrial Automation Co. points out that a significant share of ŌĆ£blankŌĆØ HMIs are simply not receiving the correct voltage at the unit, even when the source supply looks fine.

At the cabinet level, verify that the incoming supply feeding the HMIŌĆÖs power supply is present and within the nameplate range. Many PanelView terminals and similar HMIs run on 24 VDC, often supplied by a panel-mounted DC supply, while some legacy units operate on 120 VAC. If that DC supply is fed through an inverter or UPS-backed bus, confirm that all devices in that chain are energized and not stuck in bypass or fault.

Then measure at the HMI side, not just at the supply output. Industrial Automation Co. stresses this point because wiring drops, loose connectors, and internal panel fuses can drop voltage between the supply and the HMI. A simple check with a multimeter at the PanelView terminals often reveals reversed polarity, low voltage under load, or a blown fuse on an internal power board. IVS Incorporated and Apter both note that these kinds of basic electrical problems frequently show up as flickering screens, distorted images, or devices that suddenly refuse to boot after a power disturbance.

From a reliability standpoint, this is also the point where power quality needs to be evaluated. If the PanelView is fed from a bus that also supplies large drives, welders, or other high inrush loads, poor discrimination and insufficient surge protection can send voltage spikes or sags straight into the HMI electronics. Apter explicitly recommends using a UPS to stabilize voltage and protect against sudden outages that trigger HMI faults or data loss. In practice, that means giving PanelView terminals their own protected DC supply, backed by a properly sized UPS or conditioned AC feed, rather than leaving them on the dirtiest part of the network.

A blank screen does not always mean a dead HMI. MonitechŌĆÖs work on PanelView Plus 600 units, along with the Industrial Automation Co. guidance on ŌĆ£blankŌĆØ screens across brands, shows that a failed backlight or incorrect brightness settings can mimic a complete failure.

A simple but powerful field trick is to shine a bright flashlight at an angle across the screen. If you can faintly see graphics or menu items, the LCD is still receiving data and the problem is the backlight or related circuitry. In those cases, replacing the LCD assembly or the backlight module is usually sufficient. Monitech describes plug-and-play LCD kits that swap in place of the original panel and often deliver a brighter, longer-lasting display than the factory part, and they report a case where a plant avoided about $10,000 in lost production by installing such kits instead of waiting weeks for OEM replacements.

If the flashlight test shows nothing and there are no relay clicks, fan noise, or any sign of life, the problem is more likely upstream power, an internal power board failure, or in rare cases a logic module problem. Fletcher MoorlandŌĆÖs refurbishment experience reinforces that internal power-supply repairs are a frequent root cause of intermittent HMI failures and outright nonstarts.

Even when the display is dark, the PanelViewŌĆÖs status LEDs can tell you a lot. Industrial Automation Co. highlights that many HMIs, including PanelView Plus units, use LED blink patterns during boot and fault conditions. A consistent pattern of flashing green and red, or specific status indicators on the logic module, may indicate a firmware issue or internal fault that is documented in the manual. Treat those codes as seriously as you would a PLC fault LED; they are a first diagnostic step, not a cosmetic feature.

If LEDs indicate normal boot but the screen appears dead, that again points toward the display assembly or its connectors. If both LEDs and screen are lifeless, go back to the power path and internal power board.

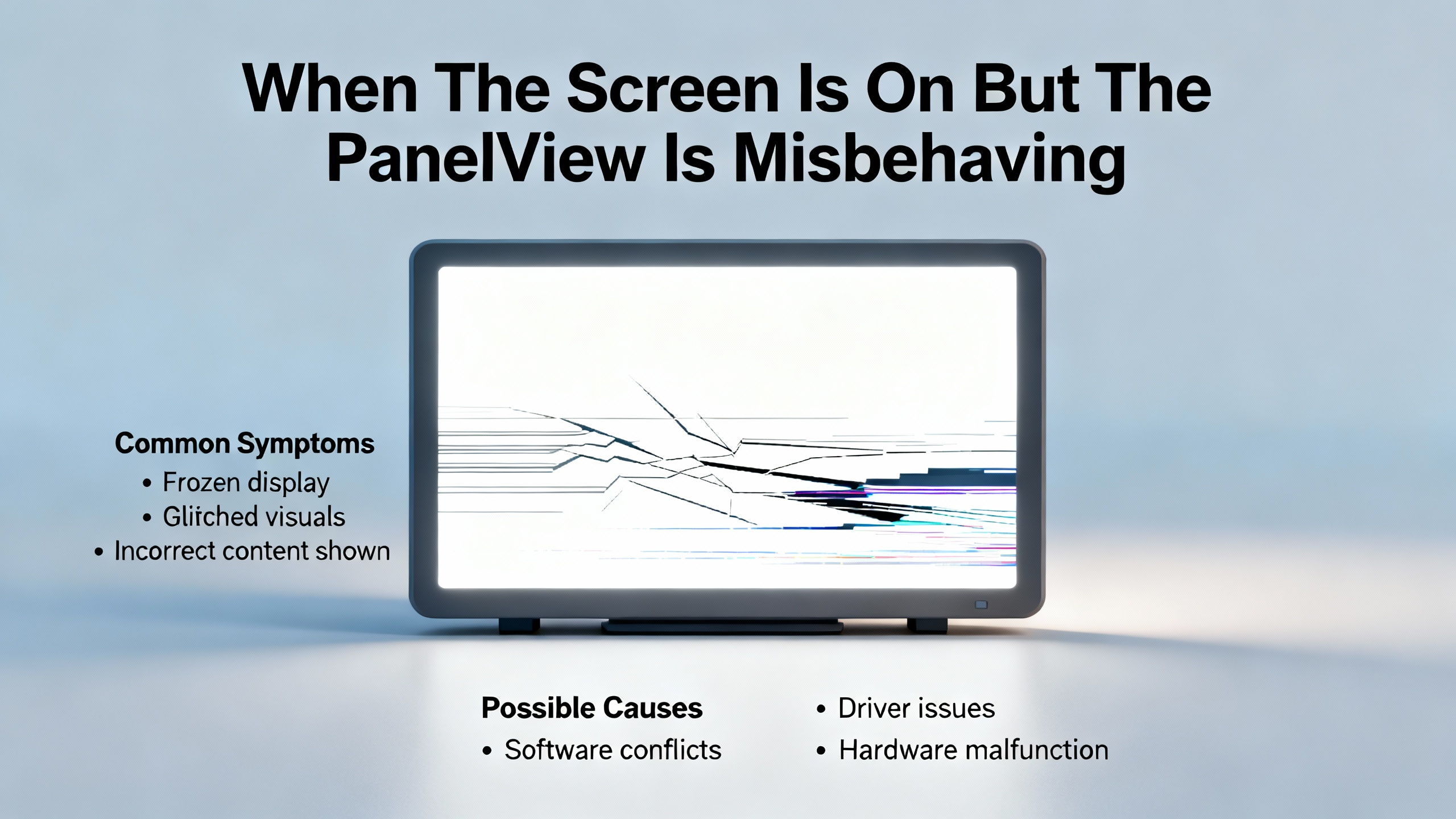

Sometimes the PanelView powers up and displays something, but the picture is garbled, the touch input is erratic, or buttons fail after changing screens. Those symptoms call for a different set of checks.

Control.comŌĆÖs discussion of a severely garbled HMI display highlights an important diagnostic principle: scope the problem. If only one PanelView on the line has a distorted screen while another on the same network is fine, you are likely dealing with a local hardware issue, not a communication or PLC problem. In such cases, basic steps include rebooting, checking all display-related cabling and connectors, and, where the HMI uses a separate monitor, temporarily testing with a known-good monitor to isolate whether the problem is the display or the controller.

Display specialists such as Monitech, Synchronics, and IVS Incorporated all describe a similar progression of display faults: first dimming and flicker, then intermittent blanking, and finally complete loss of backlight or obvious physical damage like cracks and black spots. Their recommended remedies are straightforward: adjust brightness and contrast to rule out configuration errors, then replace the LCD or complete screen assembly when hardware degradation is evident. Fletcher MoorlandŌĆÖs refurbishment services are built around that pattern, routinely replacing backlights, upgrading to LED backlighting, and fitting new membranes and keypads to restore a usable interface.

From an electrical perspective, persistent flicker, especially synchronized with large motor starts or heavy load switching, deserves a power-quality check before you condemn the screen. IVS points out that incorrect voltage, surges, and unstable power supply can all produce flickering or distorted images. If multiple HMIs in the same area show similar behavior after a large UPS transfer, generator start, or drive trip, the problem may lie in the power distribution or grounding scheme rather than in the individual displays.

Touch issues are some of the most frustrating faults because they blur the line between hardware and software. Xinje, Synchronics, Aknitech, and DriveFix all emphasize a combination of physical and configuration checks.

Begin with a visual inspection. Cracks, deep scratches, or delamination of the overlay can easily cause dead zones or phantom touches. If such damage is present, cleaning will not cure it; the panel or overlay needs replacement. Fletcher Moorland, Synchronics, and Monitech all treat touchscreen replacement as routine work, often bundling it with LCD replacement for older units.

If the surface looks intact, clean it carefully with a soft, lint-free cloth and an appropriate cleaner while the unit is powered down. Dirt, grease, and residue are common culprits for poor responsiveness. After cleaning, use the PanelViewŌĆÖs calibration function to realign touch input with on-screen elements. Manufacturer documentation and experience from repair houses show that calibration drift is a frequent cause of ŌĆ£wrong buttonŌĆØ complaints even when the hardware is not damaged.

Ghost touches, where screens register inputs without being touched, can indicate overlay failure or software corruption. Aknitech recommends updating firmware and drivers and even performing a factory reset in severe cases, but always after taking a thorough backup of the HMI project and configuration. If the PanelView still runs the runtime file but touch is unreliable, connecting a USB or PS/2 mouse, as suggested by Industrial Automation Co., can help confirm that the underlying interface and application are healthy and that the fault lies in the touch layer.

In environments using UPS and inverter-backed supplies, remember that frequent micro-outages or brownouts can corrupt touchscreen controller firmware over time. Ensuring ride-through with properly configured UPS protection, rather than relying purely on the PanelViewŌĆÖs resilience to dips, will reduce these hard-to-trace intermittent touch issues.

Allen Bradley PanelView terminals are generous with error codes, and they are far more than cryptic numbers. A buyerŌĆÖs guide from TCI Supply that catalogs common PanelView error codes shows clear patterns linking codes to trouble categories and first troubleshooting steps.

Here is a high-level view of those categories based on that guide:

| Category | Example PanelView codes | First checks |

|---|---|---|

| Display or screen reference | 403 (missing or misreferenced display) | Confirm the display name or number exists and is correctly referenced |

| Tag and communication | 662, 683, 4101, 4102 | Verify tags, controller status, network paths, and communication settings |

| Storage and memory | 1101, 1110, 2358 | Check free space, log directories, and memory allocation; delete clutter |

| Application runtime | 31, 1009, 1103, ŌĆ£Failed to Launch ApplicationŌĆØ | Validate the .mer file, startup project, and firmware compatibility |

| Licensing and feature support | 2218, 4177 | Confirm licenses and that requested features are actually supported |

| Components and paths | 4121, 4169, 4408 | Check ActiveX controls, file and comm paths, and parameter file presence |

| Communication service | 60 | Confirm RSLinx Enterprise or FactoryTalk Linx is running and configured |

The display-related error code 403, for example, indicates that the PanelView cannot find the designated display. TCI Supply advises verifying that the screen name or number actually exists in the HMI project and that PLC logic or navigation buttons reference a valid display. This kind of issue is often introduced during last-minute project edits and has nothing to do with the physical hardware.

Codes like 662, 683, 4101, and 4102 map to tag and communication problems. They typically mean the PanelView is trying to read or write data from a tag that does not exist, from a controller that is offline, or through a broken communication path. Corrective actions from the TCI guide include checking tag names and addresses carefully, ensuring the PLC is powered and in the correct mode, confirming shortcut and path configurations, and checking IP addressing and node numbers for conflicts.

Storage and memory alerts, such as 1101, 1110, and 2358, point to memory allocation failures, lack of space for logs, or inability to create files. The recommended response is to reboot the terminal, remove unneeded files and historical data, and confirm that log directories or external storage media are present and writable. For plants relying on PanelView terminals to log critical process data, this should trigger not only a cleanup but also a review of log retention policies and external archiving.

Application runtime errors, including 31, 1009, 1103, and an explicit ŌĆ£Failed to Launch ApplicationŌĆØ message, mean the terminal cannot load or start the runtime .mer file. The TCI article recommends checking that the correct runtime file is selected as the startup application, validating that the file is not corrupted, and confirming that the runtime version matches the firmware and operating system version on the PanelView. This is a common failure mode after a firmware upgrade or when swapping runtime files between different PanelView models.

Licensing and feature support codes such as 2218 and 4177 fall into a different category. These indicate activation or license issues, or attempts to use features that the particular PanelView or firmware does not support, such as certain types of alarm history. The remedy is to install valid licenses, ensure that all necessary components are properly activated, or disable unsupported functions.

Finally, codes like 4121, 4169, 4408, and 60 touch on component loading and communication services. The TCI guide notes that 4121 refers to failures loading an ActiveX control, while 4169 and 4408 highlight invalid communication or file paths and missing or corrupted parameter files. Code 60 specifically indicates that the communication service, referred to as RSLinx Enterprise or FactoryTalk Linx on the terminal, is not running. These errors call for checking installed components, verifying all paths and filenames, and in the case of communication services, restarting the terminal and checking for needed firmware or software updates.

Understanding these codes transforms troubleshooting from guesswork into a targeted process. Instead of immediately suspecting the PanelViewŌĆÖs hardware or the power system, you can separate configuration and software issues from genuine electrical or hardware faults.

Multiple sources, including XinjeŌĆÖs HMI troubleshooting guidance, a LinkedIn control engineering article, and Industrial Automation Co.ŌĆÖs network diagnostics, point toward the same lesson: jumping straight to screen replacement or a factory reset wastes time and money. A structured workflow yields better results and preserves diagnostic visibility.

The first stage is to clearly describe the abnormal symptoms. Capture exactly what operators see: a blank screen with status LEDs on, specific error codes, touch regions that are unresponsive, or alarms that appear only after changing screens. Xinje emphasizes that vague descriptions like ŌĆ£HMI not workingŌĆØ make targeted troubleshooting almost impossible.

The next stage is hardware and power verification. The LinkedIn piece highlights the importance of confirming the health and configuration of power supplies, cables, connectors, sensors, and the PLC itself before blaming software. Use a multimeter to measure voltage and continuity, and in more complex systems, an oscilloscope or logic analyzer to view signal integrity and noise. Visual inspection is just as important; look for signs of heat damage, corrosion, cracked housings, broken mounts, or loose terminal screws.

Once hardware checks pass, verify software, configuration, and network communication. For Ethernet-based PanelView systems, Industrial Automation Co. recommends basic network tests such as ping between the HMI, PLC, and any switches, followed by deeper inspection with tools like Wireshark to identify duplicate IP addresses, misconfigured ports, or NAT issues. Xinje also warns that incorrect communication addresses and COM port parameters, or damaged serial and Ethernet ports, frequently cause HMIŌĆōPLC disconnects.

Only after hardware and communication checks should you attempt recovery actions such as restarts, firmware upgrades, or factory resets. DriveFix and Aknitech both note that frozen or corrupted interfaces often recover after system restarts or firmware updates, but they stress taking backups of configuration and runtime files first. A factory reset should be a last resort, applied only after securing full backups, because it wipes all settings and runtime applications.

The final stage is documentation and prevention. Xinje recommends logging the symptom, root cause, and corrective actions each time an HMI incident occurs. That log, combined with regular maintenance intervals of roughly every three to six months, helps production teams spot patterns such as repeated power events, recurring network misconfigurations, or specific PanelView units that are approaching end of life.

Once you have narrowed down the fault, the next decision is economic and strategic: repair in-house, send the PanelView out, or replace it entirely.

Repair specialists such as Industrial Automation Co., Monitech, Fletcher Moorland, Synchronics, and IVS make a compelling case that repair is often the most cost-effective path when the core logic is still sound. Industrial Automation Co. reports that when the CPU and mainboard remain healthy, repairing display, backlight, or input modules typically costs between thirty and sixty percent less than buying a new HMI, and that turnaround times can be on the order of a few business days. Monitech describes a case where a facility avoided weeks of downtime and a five-figure production loss by installing aftermarket PanelView Plus display kits within a day rather than waiting for OEM terminals with four-week lead times.

Professional repair houses also bring specialized capabilities that most plants lack. Fletcher Moorland operates dedicated workshops for diagnosing and testing a wide range of HMI brands, including Allen Bradley PanelView units, and they routinely replace backlights, convert to LED backlighting, fit new membranes and keypads, and repair or replace internal power supplies. Their use of a secure off-site software backup service ensures that the HMIŌĆÖs project data is preserved even if the hardware is badly damaged. Synchronics and IVS similarly focus on PCB-level diagnostics, connector repair, and power supply refurbishment, along with thorough cleaning and burn-in testing.

Replacement becomes the better option when damage is severe, when the required parts are obsolete or unavailable, or when repair costs approach or exceed roughly half the price of a new unit. Xinje explicitly suggests using the fifty percent cost threshold as a rule of thumb; if repairing an aged HMI costs more than that, consider replacing it with newer hardware. Some users mitigate risk by doing both: repairing the failed PanelView for use as a spare while ordering a new unit to keep the line running.

Annual Maintenance Contracts, as described by DriveFix, can bridge the gap between individual repairs and full replacement. These contracts usually include regular inspections, firmware updates, hardware checks, and defined response times for emergencies. For plants with many HMIs, particularly across critical power and control systems, AMCs can significantly reduce unplanned downtime by catching screen, touch, and power issues before they cause outages.

Every lost HMI is a lesson in what the power system and maintenance program did not prevent. The same sources that document common display failures also converge on a set of preventive measures that align closely with good power-system design.

Power quality is the foundation. Apter recommends using UPS protection specifically to isolate HMIs from sudden outages and voltage events that can corrupt data and firmware. IVS adds that power supply problems are a leading cause of flickering, distorted, or dead screens, and that consistent use of regulators, surge protection, and well-designed UPS systems dramatically reduces such failures. In practice, that means feeding PanelView units from stable, filtered supplies, avoiding long, lightly protected runs parallel to high-current motor cables, and auditing cabinet grounding and bonding.

Environmental and mechanical protection comes next. Apter and IVS both highlight the damage caused by dust, moisture, vibration, and impacts. Enclosures should be appropriately rated for the environment, with dustproof, waterproof, and shock-resistant features where needed. Mounting hardware deserves the same level of attention; HMIs are often mounted on moving equipment, and worn mounts can lead to falls and repeated shocks, which are a short path to cracked screens and damaged internals.

Software hygiene and backups are just as important to reliability as power and hardware. Xinje urges regular backups of HMI configurations, control programs, and data so that a failed PanelView can be replaced or factory-reset without days of reengineering. Fletcher MoorlandŌĆÖs off-site software storage and the TCI Supply emphasis on correct .mer file selection show how much of HMI downtime is tied to configuration rather than electronics. Keeping firmware up to date, as recommended by DriveFix, Synchronics, and IVS, closes known bugs, reduces software-related crashes, and ensures compatibility with new runtime files.

Finally, operator and maintenance training is a form of protection. IVS notes that proper handling and shutdown procedures reduce accidental damage and software corruption, while Industrial Automation Co. and AutomationDirect stress the value of observing real operators using HMIs to identify awkward workflows or misuse, such as pressing excessively hard on touchscreens or using tools instead of fingers. When staff understand both the capabilities and the fragility of an HMI, they are more likely to report early symptoms like dim screens, slow touch response, or intermittent alarms before a complete failure.

A blank display with normal LED behavior often indicates a backlight or LCD failure rather than a total HMI failure. Monitech and Industrial Automation Co. both describe cases where shining a flashlight across the screen reveals a faint image, confirming that the logic and video signal are present while the backlight is not. In such cases, replacing the LCD or backlight assembly is usually sufficient, and the rest of the PanelView hardware can remain in service.

Purely from a hardware standpoint, a PanelView can run without a UPS, but multiple sources show that unstable power is a leading cause of HMI failures and data corruption. Apter specifically recommends UPS protection to shield HMIs from sudden outages and voltage dips, and IVS links power disturbances to flickering, dead screens, and corrupted firmware. In plants where production and safety depend on those HMIs, protecting them with a properly sized UPS and good surge protection is one of the highest-value reliability upgrades you can make.

A factory reset can clear deep software corruption, but it erases all configuration, runtime applications, and settings. DriveFix, Aknitech, and Xinje all advise treating reset as a last resort after backing up every critical file. If you do not have current backups of the .mer application and communication settings, resetting may turn a recoverable fault into a much longer outage while engineers rebuild the project. When in doubt, take an image of the terminal or involve a repair or integration specialist before resetting.

A PanelView that will not boot, a touchscreen that behaves unpredictably, or a screen that goes dark during a power event is not just an HMI problem; it is a reliability problem that reaches into your power system, network, and maintenance strategy. By starting with disciplined power and hardware checks, reading and acting on error codes, using structured troubleshooting, and engaging professional repair where it makes economic sense, you can keep Allen Bradley HMIs stable, extend their service life, and protect the uptime of every UPS-fed, inverter-driven process they control.

Leave Your Comment