-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When you walk into a control room and see Allen-Bradley PLCŌĆæ5, SLC 500, or early MicroLogix racks quietly running, it is tempting to view them as ŌĆ£good enough.ŌĆØ Many of these systems have delivered two or three decades of service. A Control.com analysis notes that well-designed control systems can operate effectively for 20 to 30 years, and in my own field work I routinely see Allen-Bradley platforms hitting that range. The problem is not that they suddenly stop working; the problem is everything that has changed around them.

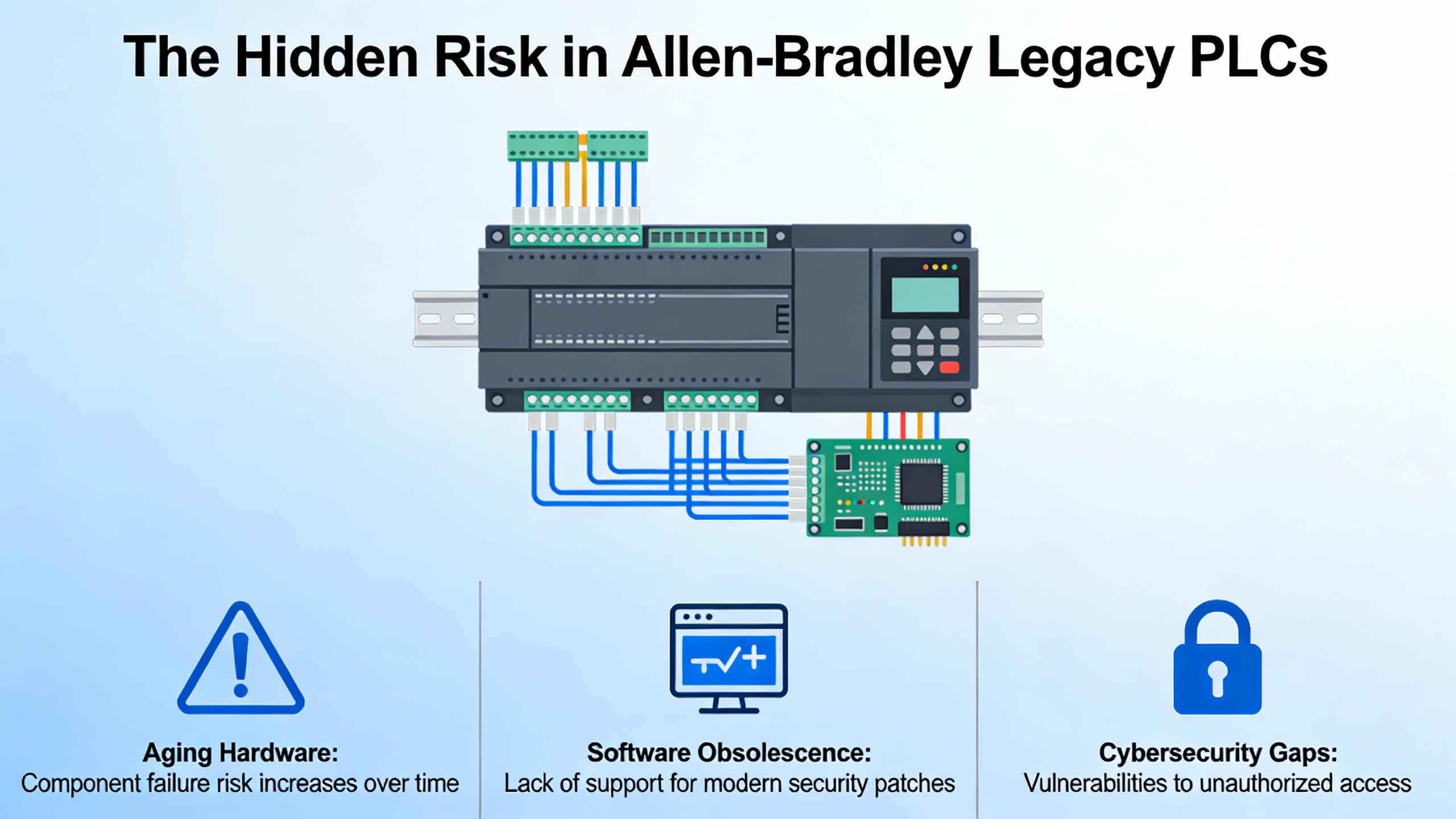

Balaji Switchgears and Panelmatic both point out the same pattern across industries. Legacy PLCs have limited processing power, poor integration with modern devices, growing cybersecurity exposure, and diminishing spare-part availability. For Allen-Bradley specifically, Applied Manufacturing Technologies and Integrity Control Services highlight that PLCŌĆæ5, SLC 500, and MicroLogix 1000/1500 families are effectively end-of-life. Rockwell Automation has consolidated around Logix-based platforms programmed with Studio 5000, while older RSLogix 5 and 500 environments no longer receive firmware or security updates.

That obsolescence directly affects reliability. E Tech Group describes a transmission-parts manufacturer that had to replace an obsolete Allen-Bradley SLC with a CompactLogix system because parts were scarce and downtime risk kept climbing. HoneywellŌĆÖs white paper on migrating legacy control systems reaches the same conclusion at the DCS level: as electronics age and support disappears, every failure becomes harder to recover from, and the total cost of ownership of staying put quietly balloons.

From a power-systems standpoint, this is more than an IT or controls concern. When a PLC tied to UPS-backed switchgear, critical pumps, or power protection equipment fails and a replacement card cannot be sourced, your ŌĆ£backupŌĆØ power strategy can unravel within hours. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs modernization work in heavy industries shows that unplanned outages from aging automation routinely cost tens of thousands of dollars per hour and create safety risks. In a forest-products case, upgrading aging PLCs across dozens of systems cut outages and delivered an estimated payback in about a year and a half.

In short, Allen-Bradley legacy PLCs can still run your plant, but the reliability, safety, and power-continuity risks around them are no longer acceptable in a modern, tightly coupled power and automation architecture.

Modernizing Allen-Bradley legacy systems is not a single decision. Several technical paths exist, and each has implications for downtime, risk, and how well your new controls will support UPS, inverters, and power protection systems.

For many plants, the most straightforward strategy is to stay within the Rockwell family and migrate to CompactLogix or ControlLogix. A guide from PLC Department describes this as ŌĆ£PLC migrationŌĆØ: moving PLCŌĆæ5 and SLC 500 programs into modern Logix controllers programmed with Studio 5000. Integrity Control Services recommends full conversions of PLCŌĆæ5 and SLC 500 to ControlLogix or CompactLogix to gain processing power, Ethernet/IP connectivity, and vendor-backed longevity, while MicroLogix 1000/1500 systems are typically upgraded to CompactLogix or Micro800 platforms.

Applied Manufacturing Technologies notes that Rockwell provides code conversion tools so RSLogix 5 or 500 projects can be translated into Studio 5000, with engineering review to clean up data structures and adapt to the tag-based Logix architecture. In practice, that means you can keep much of your proven control logic while moving it onto a controller that integrates natively with Ethernet/IP networks, modern HMIs, industrial historians, and analytics platforms.

E Tech Group describes a pragmatic version of this approach in their SLC-to-CompactLogix project. They used a Rockwell conversion kit that allowed existing wiring and mounting hardware to be reused. By preserving I/O terminations and panel layout, the team minimized labor and reduced downtime while still landing on a current Allen-Bradley platform. For plants that must coordinate with critical power equipment, this direct migration strategy often offers a manageable risk profile because field wiring to UPSs, protective relays, and switchgear-mounted I/O can remain untouched.

The trade-off is that a direct migration may not fully exploit advanced features of modern platforms. Balaji Switchgears points out that simply swapping hardware while retaining the same program architecture does not deliver the full benefits of Industry 4.0 capabilities such as deep analytics, advanced diagnostics, or cloud integration. That is where broader architectural changes come into play.

A concise comparison of key Rockwell-centric options looks like this:

| Legacy family | Typical modern platform | Key modernization tactic | Primary benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLCŌĆæ5 | ControlLogix | Code conversion tools plus I/O conversion kits | Modern CPU, Ethernet/IP, preserved logic and wiring |

| SLC 500 | CompactLogix or ControlLogix | Conversion chassis, wiring adapters, partial logic cleanup | Reduced downtime, scalable architecture |

| MicroLogix 1000/1500 | CompactLogix or Micro800 | Program re-targeting, panel rework | Higher performance, more memory, better data handling |

Not every facility is ready for a complete leap to a new controller platform. In plants that run around the clock or operate safety-critical equipment, the priority is often to reduce downtime and avoid touching validated logic wherever possible. Several sources describe hybrid approaches that keep existing PLC code while modernizing hardware and networks around it.

ProSoft TechnologyŌĆÖs guide to the ANŌĆæX4 modernization gateway illustrates a powerful example. This device can sit between legacy Allen-Bradley networks such as Remote I/O and Data Highway Plus and modern EtherNet/IP controllers. In Remote I/O Adapter Mode, it allows a ControlLogix or CompactLogix controller to monitor block transfers and I/O on an active Remote I/O network without consuming a drop, so the legacy PLC can continue running while the new PAC is commissioned in parallel. Other modes bridge DH+ to EtherNet/IP or Modbus TCP, support HMI upgrades to PanelView Plus over Ethernet without PLC code changes, or replace legacy Remote I/O drives with EtherNet/IP PowerFlex drives while preserving existing logic.

Industrial Automation Co. describes another hybrid tactic focused on ŌĆ£smart replacements.ŌĆØ They help plants identify direct-fit replacements for aging drives and PLCs that match the legacy deviceŌĆÖs voltage range, connector pattern, and communication standard. The goal is to ŌĆ£swap and startŌĆØ without rewriting ladder logic or rewiring panels. Real-world projects reused wiring paths and terminal blocks while updating to modern drives and PLCs, achieving cleaner cabinets and higher reliability without weeks of reprogramming.

ContecŌĆÖs PLC upgrade checklist reinforces this philosophy for larger systems. Their engineers often begin by replacing only obsolete electronic hardware, using adapters to keep existing wiring and connectors in place so the original software runs with minimal change. Once this hardware layer is stable, the updated logic is deployed in a second phase, with a defined rollback path and even connector replacements deferred to future maintenance windows.

Hybrid strategies excel in environments where continuous production and safety cases make big-bang cutovers unacceptable. The cost is architectural complexity: you now manage a mix of old and new networks, devices, and diagnostic capabilities. Over time, that mix should be simplified toward a fully modern Ethernet/IP-based architecture, but the hybrid phase buys you breathing room to do it safely.

Even within Allen-Bradley migrations, you face a strategic choice between minimal change and deep modernization. Vertech describes this at a generic controls level as ŌĆ£hardware-only obsolescence migrationŌĆØ versus ŌĆ£hardware and software migration.ŌĆØ Panelmatic makes a similar distinction between PLC migrations that keep panels and wiring and full PLC replacements that rebuild panels, HMIs, and power infrastructure.

In a hardware-only refresh, you replace obsolete PLC hardware with compatible modern units, sometimes using conversion kits, but keep the existing logic as intact as possible. Vertech notes that this path is lower cost and lower risk in the near term, but gains in efficiency or functionality are limited. It is best suited to systems that will be decommissioned in a few years, or where the existing logic already implements best practices and additional features add little value.

In a full overhaul, you replace hardware and rewrite the PLC program with modern software practices and high-performance HMIs. DecowellŌĆÖs guidance on IEC 61131ŌĆæ3 programming underlines how modular design, clear naming conventions, robust diagnostics, and layered architectures can significantly improve maintainability and scalability. Pattie EngineeringŌĆÖs case study shows that a complete software rewrite, while more work, can eliminate cumbersome recovery procedures and dramatically reduce restart times after faults. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs forest-industry example demonstrates that modernizing PLCs and networks, combined with better diagnostics and redundancy, can deliver a strong financial return when outages are costly.

A side-by-side view of these strategies clarifies the trade-offs.

| Strategy | What mainly changes | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware-only refresh | PLC chassis/cards, minimal code adjustments | Lower immediate risk and cost, shorter downtime | Limited functional gains, legacy logic and practices persist |

| Hardware plus software overhaul | PLCs, networks, logic, HMI, diagnostics | Better performance, maintainability, future scalability | Higher engineering effort, more extensive testing required |

For power-critical systems, the recommended path is often a staged version of the second option. You first stabilize hardware and networks to reduce immediate failure risk, then progressively refactor logic and HMIs with rigorous testing so that, when a power event occurs, your controls handle it predictably rather than compounding the disturbance.

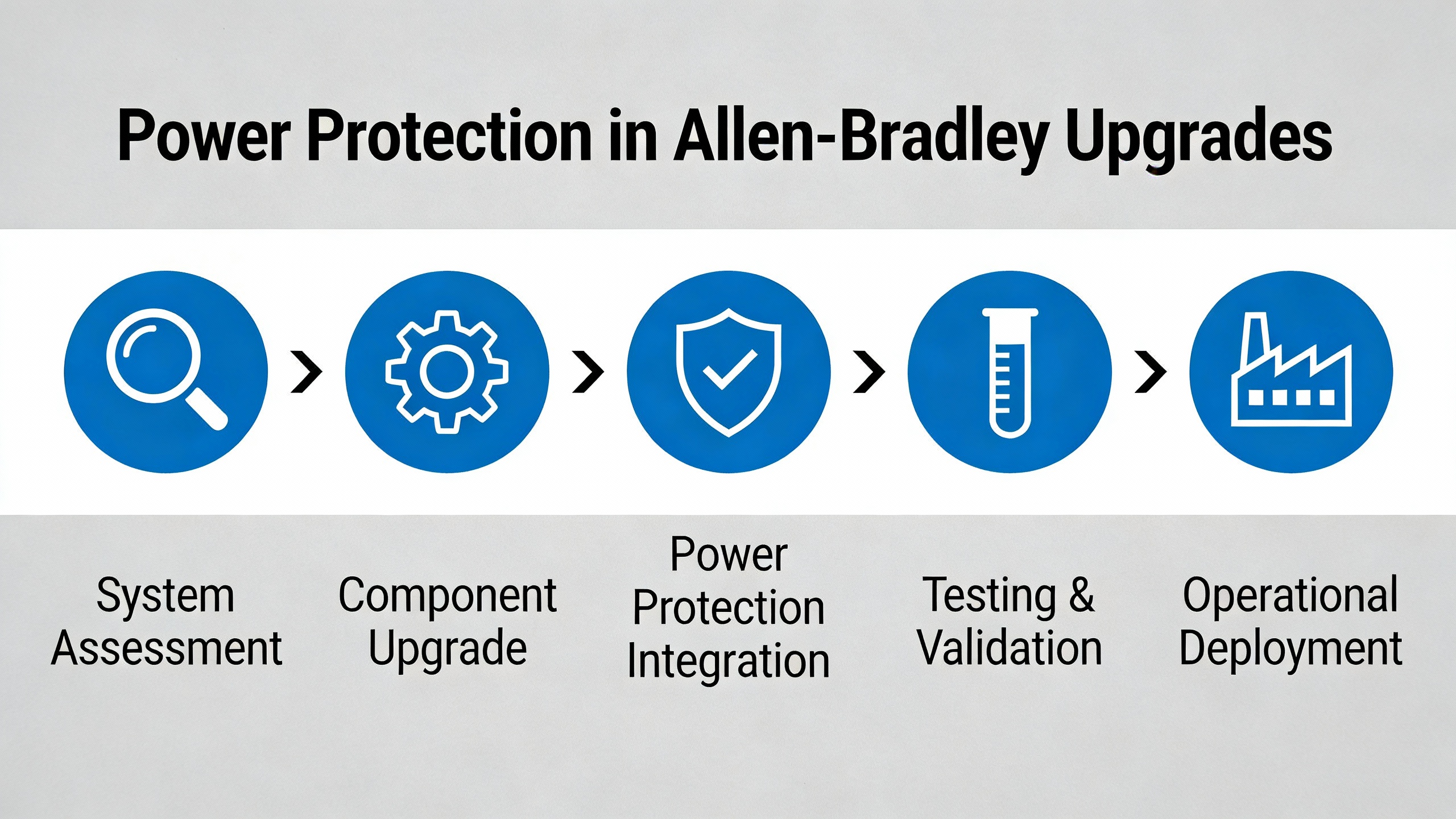

Technical choices matter, but execution quality is what keeps a PLC migration from turning into a reliability incident. Across Contec, Applied Manufacturing Technologies, Pattie Engineering, Pro-Tech Systems Group, Crow Engineering, Vertech, and RL Consulting, the same planning pattern keeps appearing: map what you have, understand risk, design the future state, plan logic migration, and test aggressively before cutover.

Applied Manufacturing Technologies emphasizes that the first planning step is a complete inventory and documentation review. That means capturing every installed PLCŌĆæ5, SLC 500, MicroLogix, drive, remote I/O rack, network segment, and power supply, along with wiring, I/O lists, and programs. Crow Engineering and RL Consulting echo this for general PLC systems, stressing that good as-built documentation is essential when legacy drawings and code comments are outdated or missing.

Contec advises mapping your installed base not just as a count of assets but in terms of obsolescence, critical nodes, unsupported components, and areas of highest risk. A practical way to apply this in an Allen-Bradley environment is to ask which PLCs or networks would halt critical processes, or compromise power protection, if they failed. That could be the PLCŌĆæ5 overseeing transfer switches and generator controls, or the SLC that coordinates large inverters feeding essential HVAC loads.

Pro-Tech Systems Group, in their discussion of upgrading legacy automation systems, recommends combining this inventory with a safety and compliance perspective. Identify which legacy controllers struggle to meet modern standards such as ISO 13849 or IEC 61508 and where cybersecurity gaps exist. The nuclear-plant PLC literature review reinforces how cybersecurity, deterministic behavior, and rigorous verification and validation dominate lifecycle decisions in high-consequence environments. While most commercial or industrial sites are less regulated than nuclear plants, adopting similar discipline for critical power and process assets is good engineering practice.

E Tech Group extends the scope of assessment beyond the PLC chassis. Power supplies, Ethernet switches, and other infrastructure components have their own lifecycles, and they should be evaluated alongside controllers. For power-system specialists, this is the moment to consider whether existing UPS units, DC distribution, and protective relays are sized and configured appropriately for the modernized controls you plan to deploy.

Balaji Switchgears recommends defining clear objectives before you select platforms. Are you primarily trying to reduce downtime, add analytics, improve cybersecurity, or standardize across sites? HoneywellŌĆÖs white paper on migrating legacy control systems urges decision-makers to think in terms of total cost of ownership and to ask what they are missing by clinging to outdated systems: lost process performance, operator effectiveness, energy efficiency, and flexibility.

For Allen-Bradley environments, the target controller layer usually centers on CompactLogix and ControlLogix, programmed with Studio 5000. PLC Department notes that these platforms offer more memory, faster processors, and better integration with HMIs, SCADA, and IIoT. Networks typically converge toward Ethernet/IP, replacing Data Highway Plus, Remote I/O, DF1, and other legacy protocols described by Applied Manufacturing Technologies and E Tech Group.

ProSoftŌĆÖs ANŌĆæX4 gateway enables a phased transition where legacy Remote I/O or DH+ networks stay online while the Ethernet/IP backbone is built out and tested. DecowellŌĆÖs best practices highlight how to design a scalable communication network using open industrial Ethernet protocols, segmented control and safety networks, structured IP addressing, and basic health monitoring of latency and packet loss.

Cybersecurity must be designed in rather than bolted on later. The nuclear-plant PLC review and RL Consulting both stress that networked PLCs introduce new attack surfaces, and standards such as ISA/IEC 62443, NFPA 79, and UL 508A should inform segmentation, access control, and patching philosophies. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs view of PLC modernization emphasizes defense in depth, pairing hardened controllers with secure communication paths and analytics that can highlight anomalies in real time. Honeywell warns against a false sense of security from legacy isolation; outdated systems can contain obsolete software and unsupported operating systems, making them difficult to protect properly.

From a power-reliability perspective, the architectural design stage is where you ensure that control networks, PLC power supplies, and UPS-backed buses are aligned. RL ConsultingŌĆÖs maintenance guidance emphasizes stable voltage, proper grounding, and environmental control around PLC panels. When you modernize, it often makes sense to standardize 24 VDC control power, coordinate PLC and network loads on UPS circuits, and ensure that switchover events do not reboot or brown out your controllers.

Once you have defined the target architecture, logic migration becomes the heart of risk management. Contec, Pattie Engineering, PLC Department, and Vertech all underscore that there is no single correct approach; the right choice depends on code quality, documentation, tool support, and system criticality.

PLC Department identifies three broad code strategies: keep the legacy system unchanged, rewrite the application from scratch, or migrate existing code with vendor tools. For Allen-Bradley migrations, code conversion from PLCŌĆæ5 or SLC 500 to Logix via Rockwell tools is often the most schedule-friendly option because it leverages proven logic. Pattie Engineering describes how automated translation tools can bring legacy programs into new environments but still require engineers to review, clean up, and thoroughly test the result. Where no tool exists and logic is stable, they sometimes perform manual line-by-line translation, adding meaningful tag names and improving readability.

Vertech and Balaji caution against copying legacy code blindly in cases where logic is already a maintenance problem. A full or partial rewrite, while more work, is an opportunity to modularize code per IEC 61131ŌĆæ3, use clear naming conventions and function blocks, and embed diagnostics and alarm structures. DecowellŌĆÖs recommended practices show how modular motor, conveyor, and alarm modules, with well-defined interfaces and status bits, make future expansion and troubleshooting far more manageable.

Testing is non-negotiable. Contec advocates building a staging environment or using simulation tools to validate new logic, confirm I/O mappings, and test operator workflows and edge-case behavior before cutover. Industrial Automation Co. recommends bench testing new drives and PLCs with the same control signals prior to production, catching misconfigurations without risking throughput. Applied Manufacturing Technologies suggests strategies such as phased cutovers, weekend swaps, and running shadow systems to minimize downtime.

Crow Engineering provides a simple but powerful calculation that illustrates why this rigor matters. A line that stops five times per day for two minutes each, across seven-day operation, loses about sixty hours of production per year. That estimate comes directly from their field experience and assumes nothing more dramatic than nuisance trips or poorly tuned logic. If your product margin is substantial, those sixty hours translate into significant lost contribution. In my own reliability reviews, I have seen that cleaning up logic during a migration and improving diagnostics can remove many of these ŌĆ£everydayŌĆØ interruptions, often with more financial impact than the main hardware upgrade itself.

Technical teams often feel that the case for upgrading Allen-Bradley legacy PLCs is obvious, but capital committees need structured justification. Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs analysis of PLC modernization economics argues that traditional ROI methods, which focus mainly on avoiding catastrophic failures, miss the continuous revenue and margin gains from better automation. Instead, they advocate combining real-time accounting and analytics to quantify production value, energy use, and material costs per unit, then tracking how modernization affects a profitability index.

In the forestry case, modernizing aging PLCs across forty-five systems that had been causing outages costing tens of thousands of dollars per hour led to reduced downtime and added redundancy and online-change capability, with an estimated payback of about one and a half years. HoneywellŌĆÖs DCS migration white paper shows a similar pattern, framing migration decisions around total cost of ownership. It encourages plants to compare the cost and risk of continuing with legacy systems against what they are missing: improved process performance, operator effectiveness, asset management, and production flexibility.

Pro-Tech Systems Group emphasizes safety and compliance in their justification framework. They argue that upgrading legacy automation, especially PLCs, is now a vital step for meeting modern safety and environmental standards such as ISO 13849 and IEC 61508, and for aligning with sustainability goals. Their perspective is that modernization should be viewed as an investment in plant safety and future competitiveness rather than a discretionary expense.

For power-system specialists, it helps to make the link explicit. Modern PLC platforms with Ethernet/IP, integrated historians, and strong diagnostics, as described by PLC Department, Schneider Electric, and PTE, make it easier to measure how power disturbances, UPS transfers, and voltage anomalies impact production performance and energy consumption. That data lets you quantify benefits like reduced scrap after voltage dips, faster restarts after utility outages, and lower energy per unit produced, all of which support a robust business case.

While most modernization articles focus on logic and networks, the intersection with UPS systems, inverters, and power protection equipment is where reliability projects either succeed quietly or fail dramatically. E Tech Group advises that lifecycle management should include power supplies and Ethernet switches alongside PLCs, and RL Consulting highlights the importance of stable voltage, grounding, and environmental control for long-term PLC performance.

Pro-Tech Systems Group and Schneider Electric both stress that modern automation platforms can track energy use and operational efficiency in real time. When you modernize Allen-Bradley PLCs, you gain the ability to pull detailed data from power meters, drives, and process equipment into analytics environments and cloud historians. Schneider Electric notes that such data can be used to calculate profitability indices and benchmark production lines, identifying where modernization yields the highest financial impact.

From a practical standpoint, this is the ideal time to ensure that critical controllers and network gear are properly backed by UPS capacity, that control power is segmented by criticality, and that PLC logic explicitly handles power events. Even though the sources here focus more on process industries than on UPS specifics, the underlying reliability principles are the same. You want PLC architectures that ride through short disturbances without rebooting, fail to a defined safe state for longer outages, and provide clear diagnostics so that maintenance teams know whether a fault was power-related or purely logical.

RL ConsultingŌĆÖs maintenance recommendations include regular validation of emergency stops, interlocks, relays, and other safety-related controls. When you integrate PLC modernization with power-system upgrades, schedule these safety checks together with tests of transfer switches, UPS bypass modes, and protective relay coordination, so that your electrical and controls layers behave as one coherent protection system.

Consider a mid-size manufacturing plant where a PLCŌĆæ5 controls a critical process line and coordinates power-related interlocks, while several SLC 500 controllers manage auxiliary systems. Communication runs over Data Highway Plus, and key PLCs are powered indirectly from UPS-fed panels, but documentation is fragmentary.

Following the patterns laid out by Applied Manufacturing Technologies, Contec, and Vertech, the team begins with an installed-base and risk assessment. They catalog all PLCŌĆæ5 and SLC racks, DH+ segments, power supplies, and panel feeders. They identify the PLCŌĆæ5 on the main line as a high-criticality node, since any failure would halt production and complicate power sequencing.

Architecturally, they choose ControlLogix as the standard controller family and Ethernet/IP as the backbone network, in line with RockwellŌĆÖs strategic direction and recommendations by PLC Department. To reduce risk, they deploy a ProSoft ANŌĆæX4 gateway in DH+ to EtherNet/IP mode, which lets a new ControlLogix processor access PLCŌĆæ5 data over the existing DH+ network without modifying legacy code. This allows them to build and test a parallel ControlLogix project while the PLCŌĆæ5 remains in charge.

For logic, they use RockwellŌĆÖs conversion tools to translate the PLCŌĆæ5 program into Studio 5000 and then apply Decowell-style cleanup: modularizing motor and conveyor control, standardizing tag names, and adding diagnostics bits and structured alarms. They adopt ContecŌĆÖs recommendation to keep wiring and connectors intact in the first phase, using conversion hardware in the PLC panel so that I/O landing points stay the same.

Testing follows Contec and Industrial Automation Co. guidance. The team sets up a staging system with a spare ControlLogix rack and a small replica of the power-interlock circuits, then drives worst-case scenarios to validate behavior. They run a shadow system, where ControlLogix observes process and power states in real time via the ProSoft gateway, comparing its computed outputs to those of the PLCŌĆæ5.

Cutover is scheduled for a weekend. Following Applied Manufacturing TechnologiesŌĆÖ best practices, they stop the line, place the power system in a safe configuration, and move I/O connections from the conversion hardware to the live ControlLogix rack. Because cabinet layouts and wiring paths were preserved, this physical work completes quickly. After a structured commissioning sequence and parallel verification of UPS and protective relay responses, the ControlLogix becomes the primary controller, while the PLCŌĆæ5 is left available as a fallback for a defined burn-in period.

Financially, the project reduces the immediate risk of a PLCŌĆæ5 failure that could have required days of scrambling for parts. Operationally, the new Logix platform, Ethernet/IP network, and improved diagnostics help the team identify and reduce ŌĆ£nuisanceŌĆØ trips similar to those quantified by Crow Engineering, cutting dozens of hours of micro-downtime per year. Because the plant now captures richer data on power events and process performance, it can start applying Schneider ElectricŌĆÖs profitability metrics to tune energy use and throughput.

Refurbished PLCŌĆæ5 or SLC 500 hardware can extend life for a while, but nearly every source in this research highlights the rising risk profile of that approach. Balaji Switchgears, Panelmatic, and Honeywell all note that as spare parts become scarce, prices go up, lead times stretch, and failures take longer to recover from. Schneider Electric and E Tech Group show that unplanned downtime is often far more expensive than planned modernization, especially on high-value lines. Refurbished parts may help you bridge to a planned migration date, but they are rarely a sustainable long-term strategy.

Not necessarily. Vertech emphasizes treating the control system as a set of subsystems rather than a monolith. In some cases, you can upgrade PLCs while leaving SCADA in place, especially if existing HMIs support Ethernet/IP or can talk to the new controllers through gateways such as ProSoftŌĆÖs ANŌĆæX4. Integrity Control Services also describes Allen-Bradley HMI modernizations that retain logic and historical data while updating PanelView hardware and screen design. Over time, however, aligning PLC, HMI, and SCADA platforms tends to reduce complexity, spare-parts inventory, and training burden, which is why many plants plan phased upgrades of all three layers.

Control.comŌĆÖs review suggests that well-designed industrial control systems can operate effectively for twenty to thirty years, and RL Consulting emphasizes that proactive maintenance, backups, and environmental control can stretch useful life. However, PLC lifecycle is no longer the only driver. Applied Manufacturing Technologies, Honeywell, and Schneider Electric all show that software compatibility, cybersecurity expectations, and business demands for data and analytics have shortened the effective support horizon for older platforms. Even if a PLCŌĆæ5 still runs, the surrounding toolchain, networks, and security posture may already be past their practical limits. In power-critical applications, waiting for a failure or a forced migration due to unsupported software is rarely a responsible choice.

Modernizing Allen-Bradley legacy PLCs is ultimately a reliability decision as much as it is a controls decision. When you treat the project as an integrated effort that spans controllers, networks, UPS-backed power, cybersecurity, and operations, you shift from defending old hardware to actively designing a resilient, data-rich control environment that supports your power-protection strategy for the next decade.

Leave Your Comment