-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

In industrial and commercial power systems, ABB variable speed drives (VSDs) and variable frequency drives (VFDs) are often the quiet workhorses behind pumps, fans, conveyors, and process lines. When those drives move into obsolete lifecycle states, the impact is rarely just a purchasing nuisance. It becomes a reliability and uptime problem.

Inverter Drive Systems defines obsolete VSDs as drives that you can no longer buy new, that have no lifecycle services, and for which replacement parts are very difficult to obtain. ABB drives can run for many years when treated well, but once a family transitions to obsolete, every failure exposes you to higher repair costs, longer outage durations, and shrinking technical support. Inverter Drive Systems explicitly calls out several ABB ranges in this category, including Sami Star, ACS300, ACS400, ACS500, and ACS600, and notes that the full obsolete and limited list is long and evolving over time.

Technology.org highlights the stakes clearly for ABB control-system parts in general: a single failed component can stop a production line and cost thousands of dollars per hour. When you combine that with an obsolete drive that nobody stocks and that ABB no longer supports, you are effectively gambling your plant’s throughput on whatever you can find in surplus channels.

A real example from Inverter Drive Systems shows how seductive repair can become a trap. One user continued repairing an obsolete ABB ACS600 instead of upgrading. When they finally compared the numbers, total spending on repairs plus standby plant and lost production had climbed to more than twice the cost of a new ABB ACS580. The message is not that repair is always wrong, but that continuing to repair obsolete drives without a plan quickly becomes irrational once you account for downtime and operational risk.

From a power-systems perspective, this matters even more in UPS-backed and critical-process environments. If an obsolete ABB drive fails on a fire pump, a critical HVAC system that keeps IT loads within safe temperature, or a conveyor feeding a high-value production line, you do not just risk a single asset. You risk cascading overloads, emergency transfers to bypass, and unscheduled generator or UPS stress.

The rest of this article focuses on how to source ABB obsolete drive parts and legacy replacements in a way that supports, rather than undermines, reliability.

ABB’s own lifecycle management approach is an important starting point when you are planning support for older drives. ABB’s refurbished parts service is structured around lifecycle phases typically referred to as active, classic, limited, and obsolete. Service availability depends on which phase a product is in.

For products in active and classic phases, ABB states that repairable parts are always offered as refurbished options. These are “like-new” components that have been recovered and updated rather than manufactured from scratch, tested to meet original equipment specifications and checked against current standards. As products move into limited and then obsolete phases, ABB often still supports repairable parts as refurbished where feasible, specifically to help users operate aging assets longer without full replacement.

In parallel, ABB runs a Pre-owned Parts (PoP) program. According to ABB’s Process Automation Service material, PoP parts are OEM-sourced used parts that primarily come from system upgrades and inventory buybacks at serviced sites. ABB positions them as higher-quality used parts because the sources are known and traceable. Each PoP unit is tested, cleaned, and repackaged in an ISO 9001 certified ABB repair center, with the intention of combining used-part pricing and controlled quality. PoP parts carry a two-year warranty from shipment, and ABB even offers a price match guarantee on qualifying in-stock PoP items for US end users. Part numbers in this program start with the letter “P,” while a related QTP category uses “R”-prefixed numbers and is searchable through ABB Business Online.

This combination of refurbished parts and pre-owned programs gives you an OEM-backed path to keep many ABB drive systems running beyond their initial lifecycle horizon, often with warranty coverage comparable to some new parts and with testing that aligns with ABB’s own standards. However, coverage is not universal. Once certain families become deeply obsolete or parts are no longer repairable, you are pushed toward third-party specialists and surplus markets.

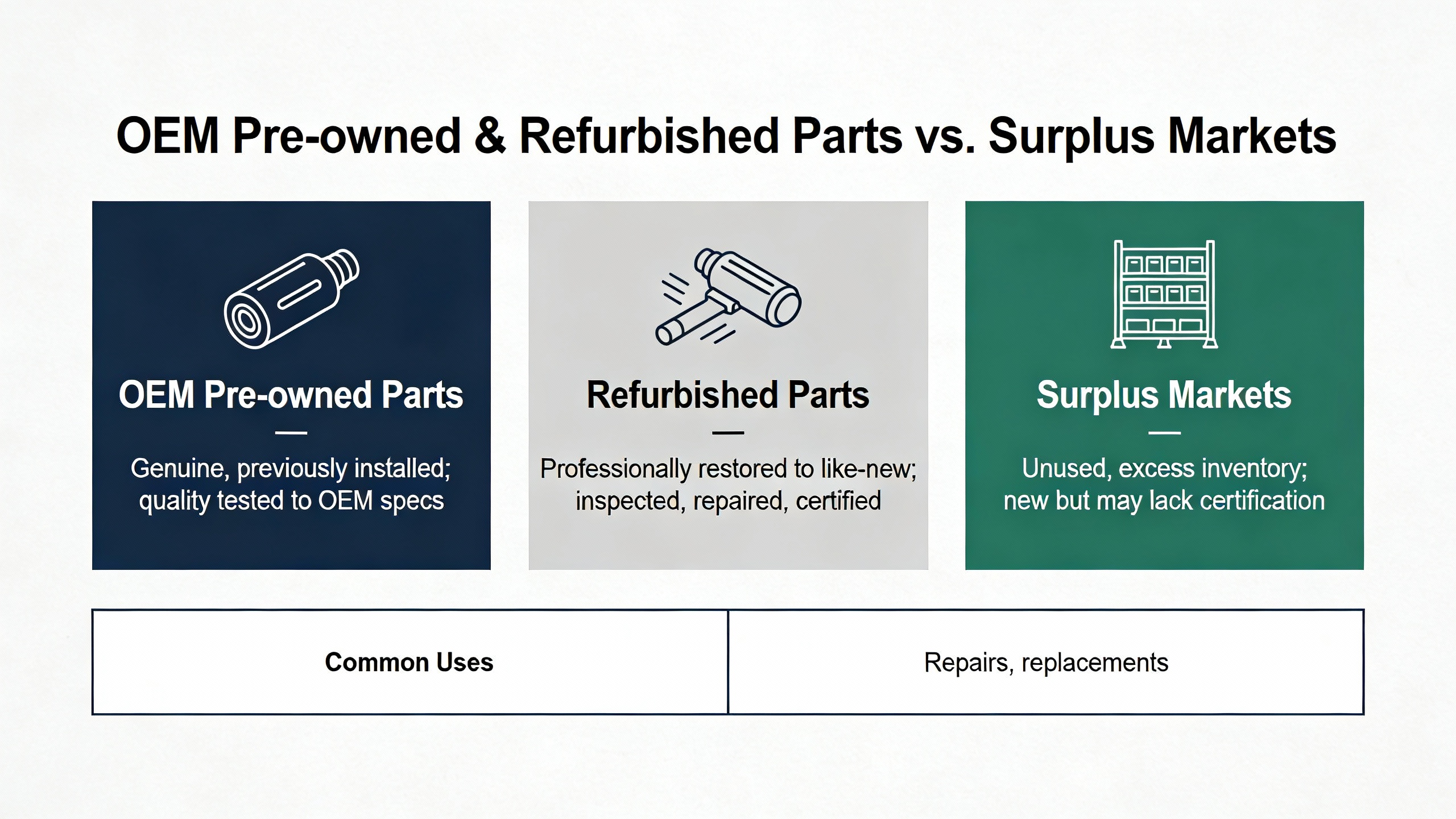

When I am advising plants on ABB legacy drive support, I usually start by mapping the realistic options for each asset: OEM-backed pre-owned or refurbished, multi-brand legacy specialists with test and warranty commitments, and more open surplus and overstock channels.

ABB’s PoP and refurbished services sit at the highest end in terms of traceability and alignment with original performance. PoP items are pulled from known sites where ABB is often already involved in service, then run through ISO 9001 repair centers. Refurbished parts are upgraded and tested to original specifications, and ABB stresses that they also conform to current component standards and safety expectations. In both cases, you are leveraging ABB’s own test procedures and documentation, and you benefit from a two-year warranty on PoP parts along with a defined replacement path if something fails.

Classic Automation sits in the middle layer as a multi-brand legacy specialist. Their ABB drives parts and repair offering emphasizes that all parts are tested in-house and are shipped with a two-year warranty. They maintain a broad inventory that includes many manufacturers far beyond ABB and GE, with some brands showing thousands of parts. That breadth is particularly valuable if your installed base is mixed, since it lets you keep legacy ABB drives and associated protection, control, and measurement equipment supported through a single partner rather than juggling many suppliers.

Surplus and overstock ABB drive channels, as described by Amikon’s guidance on overstock ABB VFD suppliers, occupy a different niche. Excess ABB VFD stock typically comes from canceled projects and over-ordering during past supply shortages, forming a pool of excess-and-obsolete inventory. These units are usually unused but may have partial documentation and uncertain storage history. The key differences among new, surplus, and refurbished drives are documentation quality, test pedigree, and traceability, not the silicon itself. Used ABB drives and parts on global marketplaces, such as those presented on Longi’s multilingual used ABB VFD listings, are another layer where technical details and warranties can be sparse and you must do more of the reliability work yourself.

Technology.org’s analysis of surplus ABB control system parts highlights why this matters. They describe typical quality and reliability concerns: unknown usage histories and storage conditions, exposure to stress, and increasingly sophisticated counterfeits with remarked date codes and substandard components. Without proper testing and traceability, degradation and microfractures may only reveal themselves under heat or vibration, which often means failure after installation rather than during incoming inspection.

The table below summarizes these sourcing paths at a high level.

| Sourcing path | Typical quality controls | Warranty and support | When it fits best |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABB PoP pre-owned parts | ISO 9001 ABB repair centers, cleaning and functional tests on OEM-sourced used parts | Two-year warranty from ABB, with defined replacement rules and US price match guarantee for qualifying PoP items | Long-term operation of ABB platforms where OEM-backed quality and known origin matter more than absolute lowest price |

| ABB refurbished parts service | Refurbishment to meet original specs, checked against current standards; availability tied to lifecycle state | Warranty through ABB’s service framework, focused on repairable items | Extending life of installed ABB equipment in active, classic, or limited phases without full system replacement |

| Legacy specialists such as Classic Automation | In-house testing on ABB parts, multi-brand inventory, two-year warranty | Technical support plus repair services for many vendors and drive families | Plants with mixed-vendor legacy equipment needing tested spares and repair under a single umbrella |

| Surplus and overstock drives from specialists like Amikon and similar vendors | Varies; some provide functional tests and inspection, others minimal screening | Often shorter warranty; depth and rigor of test reports vary widely | Cost-sensitive cases where new or OEM-backed parts are unavailable and the site can absorb higher reliability and integration risk |

For critical UPS-backed loads, process-safety functions, or where a trip would cause large environmental or safety impacts, I strongly favor staying within the ABB and high-end legacy-specialist paths until there is no realistic alternative. For noncritical fans, secondary conveyors, or backup systems, surplus channels can be a rational part of the strategy, provided they are vetted carefully.

Sourcing the part is only half the problem; integrating it correctly is where most outages are created. Three types of risk show up repeatedly in the sources: firmware and communications mismatches, thermal and electrical misapplication, and environmental and counterfeit risks.

Technology.org describes a real case where a surplus ABB drive was procured with a different fieldbus protocol than the installed base. The new unit’s hardware could not communicate correctly with the existing controller, leading to a three-day plant shutdown. They also highlight firmware mismatches, for example a controller expecting firmware version 3.2 trying to talk to a module on 2.8, causing communication deadlocks.

Industrial Automation Co. emphasizes this same integration layer when discussing replacements for discontinued drives. They stress that drive replacement is an engineering decision rather than a simple horsepower swap. You have to preserve or improve performance, communications, and reliability without major panel or program redesign. That means confirming support for industrial networks such as EtherNet/IP, Modbus RTU or TCP, PROFINET or PROFIBUS, and CANopen or DeviceNet, as well as accounting for I/O mapping, encoder feedback, and diagnostics. Many modern drives include web servers for remote monitoring and parameter tuning, which can replace older RS-232 based service methods but require rethinking commissioning workflows.

In practice, this means that when you source an obsolete ABB drive or a functional equivalent, your purchasing specification must extend beyond part number and voltage. It should include required network protocol, expected firmware major version, control-word structure, and any critical diagnostic or parameter features needed by your PLC or DCS logic.

Electrical and thermal misapplication is another common failure pattern when teams scramble to keep legacy drives running. Amikon’s guide to overstock ABB VFD suppliers makes several points that are particularly relevant.

They remind buyers that drive sizing should be based on voltage and motor current, especially maximum current under worst-case torque, rather than nameplate horsepower alone. Across-the-line motor starts can exceed eight times motor full-load amps, and while VFDs help by limiting inrush, constant-torque applications such as conveyors and mixers still demand high breakaway torque. A surplus drive that looks fine on horsepower but is optimized and sized for a lightly loaded fan can be over-stressed and fail early on a heavily loaded conveyor.

They also provide specific derating guidance. Ambient temperature ratings for many drives run from about 14 to 32°F on the low side up to roughly 104°F on the high side. Above that, continuous current capability typically derates roughly one percent for about every 2°F increase in temperature up to around 122°F. Altitude derating is also significant, roughly one percent reduction in continuous current per additional 328 ft above about 3,280 ft, leading to about a fifteen percent derate by around 8,200 ft. For the frequent case of feeding a three-phase drive with single-phase supply, Amikon recommends treating continuous capability as roughly fifty percent of nameplate current and upsizing the drive so its current rating is about twice the motor’s full-load amps.

Consider a simple example. Suppose you source a surplus ABB VFD rated for 40 A at sea level with a top ambient of 104°F and install it in a mountain facility at around 8,200 ft where the electrical room regularly runs near 113°F. You have already lost around fifteen percent of continuous current for altitude, bringing effective capacity to about 34 A. Then you take another roughly five percent hit for temperature above 104°F, leaving you near 32 A. If your motor needs 34 A continuously at worst-case torque, that surplus drive is undersized in the real environment, even though its nameplate looked safe. This is exactly the scenario where drives quietly run hot, nuisance trip on overload, and die early, often taking upstream protection devices along with them.

Industrial Automation Co. further underscores the need to align mechanical and thermal characteristics such as frame size, mounting, enclosure rating, cooling method, and airflow direction. A replacement that physically fits into an existing panel but disrupts airflow or violates enclosure ratings can compromise both safety and reliability, especially in tight UPS and critical power rooms where every watt of heat and every square inch of clearance matters.

Amikon and Technology.org converge on environmental stress and storage as major reliability drivers for surplus ABB drives. Heat is described as the number one killer of drives; cooling fans are wear items that should be replaced proactively; and dust and debris on heat sinks and fans impede cooling. Condensation or leaks can corrode boards and cause intermittent faults and outright failure.

For surplus ABB drives with unknown storage histories, Amikon recommends thorough visual inspection for discoloration, corrosion, dust, and moisture, checking enclosure integrity, fans, and filters, and either rejecting or sending for technical evaluation any units showing obvious contamination or heat damage. Technology.org extends this with a more formal evaluation process: detailed visual inspection of solder joints and capacitors, burn-in testing at elevated temperature for several dozen hours, and use of ABB diagnostic tools to read operating hours and fault logs where available.

Counterfeit and substandard parts are another concern raised by Technology.org. These may use lower-grade capacitors and poor thermal design that pass a quick bench test but degrade rapidly under real process duty with thermal cycling and vibration. This is where sourcing from ISO 9001 certified vendors, demanding traceability back to original decommissioning sources, and insisting on recent test reports becomes more than a quality preference; it becomes a risk-control strategy.

While sourcing obsolete ABB drive parts, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that the cheapest reliability risk is the one you never create. Two themes in the sources reinforce that idea: data-driven maintenance and disciplined simplicity.

ABB’s condition-based maintenance approach for variable speed drives, described in depth by Inverter Drive Systems, uses existing drive sensors to move away from fixed time-based preventive maintenance. Drives already measure key quantities such as temperature, voltage, and power. By collecting that data at one-second intervals, a single drive can generate around 200 GB of data per year. ABB’s cloud analytics use this data to predict remaining life for key components such as cooling fans, semiconductor converter modules, and DC link electrolytic capacitors.

Working with component manufacturers, ABB derived L10 life curves that estimate how long ninety percent of components will last under given conditions. Cloud algorithms translate stress histories into remaining lifetime curves for each component and the drive as a whole, with thresholds that flag when replacements should be planned. In practice, that allows reliability engineers to look one to two years ahead and see which drives will need component swaps or replacements, and when. It also reveals drives that are under-stressed, where operation can be extended beyond nominal service life without increasing risk.

In one steel rolling mill case, a drive’s converter module was flagged as end-of-life. Because the recommendation was not followed, the module failed about four months later, validating the model. After replacement, the condition-based maintenance system projected a seven-year change interval, consistent with the original failure timescale. Another example described by Inverter Drive Systems is the Aero Gravity free-fall simulator in Milan, a roughly 69 ft high and 16 ft wide wind tunnel where six 400 kW fan-motor-drive systems ramp airflow from about 75 mph to about 230 mph in seconds. Cloud-based monitoring there tracks abnormal temperatures and incorrect operations, reducing thermal stress and improving efficiency and user comfort.

The common thread in both examples is that data reduces surprises. Even if you must continue running an obsolete ABB drive because there is no immediate upgrade budget, having accurate remaining-life estimates for its fans, power modules, and capacitors lets you plan component replacements while parts are still available, instead of scrambling for obsolete spares after a failure.

MB Drive Services complements this with a conceptual guideline: the KISS principle, or “Keep It Simple, Stupid.” Applying KISS to drive systems means resisting the temptation to bolt on overly complex workarounds or custom logic, especially when dealing with obsolete hardware. Each extra conversion layer, protocol bridge, or bypass contactor is another potential failure point. In legacy ABB drive support, simplicity often looks like a clean, well-documented architecture, using standard components and avoiding exotic, hard-to-maintain hacks to keep old drives alive at any cost.

When you combine ABB’s lifecycle tools, the realities of surplus markets, and the cost of downtime, a practical strategy for ABB obsolete drives emerges. It revolves around three recurring decisions: when to replace rather than repair, how to choose the right sourcing path for the drives you must keep, and how to size your spares and monitoring to avoid emergency buying.

First, consider when to stop repairing and invest in replacement. Inverter Drive Systems’ ACS600 example shows that once cumulative repair and downtime costs exceed the price of a modern drive by a factor of two, you are almost certainly past the rational replacement point. Even before you reach that ratio, remember Technology.org’s reminder that a single ABB control-system failure can cost thousands per hour. If your line is worth, for example, $5,000.00 per hour in contribution margin and a drive failure extends your outage by eight hours while you search for an obsolete part, you have just spent $40,000.00 in lost production, not counting maintenance labor and scrap. If a new ABB drive or a modern equivalent plus a well-planned shutdown would have cost much less, the “cheap” repair was not actually cheap.

Second, for drives you must keep running in the medium term, decide which sourcing path fits each application. For safety-critical or environmentally sensitive loads, such as wastewater treatment blowers or fire pumps, ABB PoP and refurbished parts, or tested parts from legacy specialists like Classic Automation, are usually worth the premium. The two-year warranty from ABB or Classic Automation is not just a financial protection; it is also a proxy for the level of testing and quality control behind the part.

For noncritical loads where downtime is manageable, carefully vetted surplus drives from specialists like Amikon and peers can be part of a cost-effective strategy. Amikon’s guidance on matching duty type, full-load amps, ambient conditions, and applying ABB’s derating curves shows how surplus can be applied professionally rather than opportunistically. However, this only works if you have the engineering bandwidth to verify those details and perform incoming inspection and burn-in tests similar to those described by Technology.org.

Third, plan your spares and monitoring. Amikon notes that ABB VFDs are usually high-value items and recommends differentiated stocking based on criticality. For critical safety or environmental loads, having an on-site spare ABB drive can be justified. For noncritical equipment, it can be more economical to rely on trusted overstock suppliers rather than stocking multiple local spares and recreating an excess and obsolete inventory problem in your own storerooms.

Condition-based maintenance, as outlined by ABB and Inverter Drive Systems, can guide this stocking strategy. Drives that show high thermal and electrical stress with remaining-life curves trending toward zero within one to two years are strong candidates for dedicated spares or accelerated upgrades. Drives that are lightly loaded and under-stressed can be de-prioritized for replacement and might even allow you to harvest parts if a truly critical unit fails.

Throughout this planning, MB Drive Services’ KISS principle is a useful filter. If keeping a particular obsolete ABB drive in service requires ever more complex bypass schemes, custom firmware patches, or undocumented tweaks, that complexity itself becomes a risk. In many cases, the most reliable solution is a straightforward replacement with a modern ABB drive or a carefully selected equivalent, using Industrial Automation Co.’s guidelines to match electrical, mechanical, and communication characteristics while simplifying the overall system.

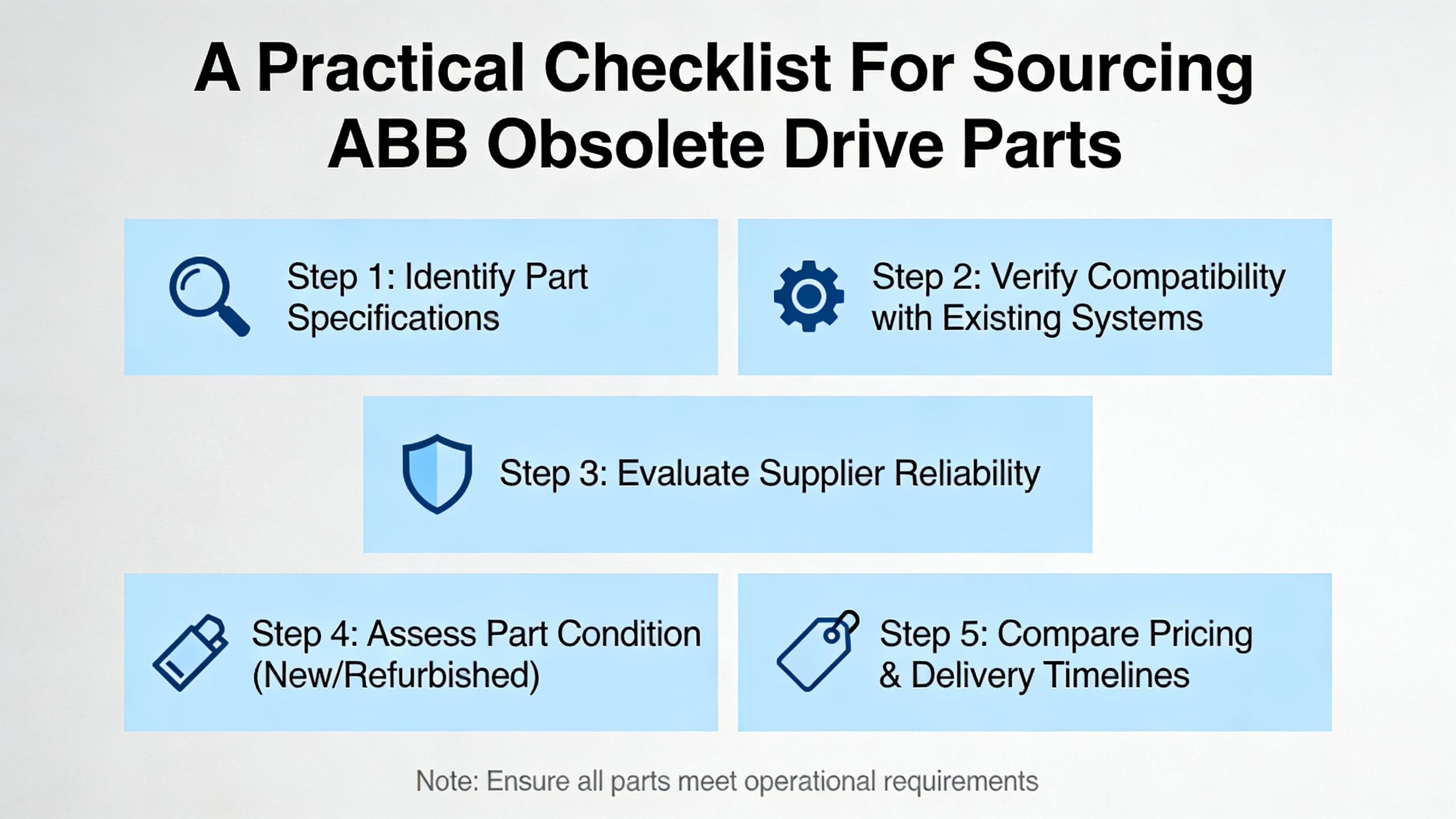

While every site and process is different, the same questions keep showing up when we evaluate ABB obsolete drive sourcing. You can treat the following as a mental checklist whenever you consider an obsolete drive part or replacement, whether from ABB, a legacy specialist, or the surplus market.

Start with specifications and derating. Confirm voltage class, motor full-load current, overload capability, and duty type, and then apply temperature and altitude derating similar to the guidance from Amikon. Make sure that after derating, the drive still covers your worst-case continuous current and torque requirements, not just nameplate horsepower.

Next, verify traceability and test evidence. OEM programs like ABB PoP make this straightforward by definition. For third-party suppliers, follow the Technology.org recommendations and ask for recent electrical and functional test reports, details on storage conditions, and clear return and RMA terms. ISO 9001 certification and specialization in automation parts are good indicators that their processes are more than ad hoc.

Compatibility and firmware are the third pillar. Use Industrial Automation Co.’s emphasis on communications and I/O to drive your questions. Specify required network protocol, anticipated firmware family, and any specific features your PLC or DCS expects. For surplus ABB drives, use ABB’s compatibility matrices and diagnostic tools where possible to ensure the replacement sits in the same firmware and option-module neighborhood as the failed unit.

Finally, evaluate warranty and cost in the context of downtime. A two-year warranty from ABB’s PoP program or from Classic Automation sends a strong signal about confidence in the part and the willingness to stand behind it. Compare any price savings from a cheaper surplus option against realistic downtime risk using the thousands-of-dollars-per-hour perspective from Technology.org and the lifecycle cost insight from Inverter Drive Systems’ obsolete drive repair example.

The table below can help structure these discussions with your suppliers.

| Evaluation area | Key questions to ask | Supporting guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical and thermal fitness | Does the derated current capacity exceed motor full-load amps under worst-case ambient and altitude? Is the drive sized for variable-torque or constant-torque duty? | Amikon’s derating rules for temperature and altitude and their emphasis on matching duty type and current rather than horsepower provide a concrete basis for this check. |

| Traceability and quality | Can the supplier show where the part came from, how it was stored, and what tests were performed, and do they offer at least a one to two-year warranty? | ABB’s PoP and refurbished services and Classic Automation’s tested-with-two-year-warranty model illustrate what strong quality control looks like in practice. |

| Compatibility and firmware | Does the drive support the same fieldbus protocol, control-word mapping, and firmware family required by your control system, and can you migrate parameters cleanly? | Industrial Automation Co.’s advice on matching industrial networks and planning parameter migration, along with Technology.org’s example of a protocol mismatch causing a three-day outage, underline why this matters. |

| Environmental resilience | Is the enclosure rating appropriate for your installation, and has the drive been inspected for heat, contamination, and moisture damage? | Amikon’s guidance on heat being the number one killer of drives and the need to inspect for dust, corrosion, and leaks is directly applicable here. |

| Lifecycle fit and economics | Is the drive family still in ABB’s active, classic, or limited phases, allowing refurbished support, or is it fully obsolete, and how does that change the cost-benefit of repair versus replacement? | ABB’s refurbished parts service and Inverter Drive Systems’ ACS600 versus ACS580 case highlight how lifecycle state shapes long-term cost and supportability. |

Surplus ABB drives from overstock channels, as described by Amikon and Technology.org, can be technically sound, especially when they are unused and stored correctly. For critical loads where a failure would cost thousands per hour or have safety or environmental implications, relying solely on surplus without strong testing, traceability, and warranty is risky. OEM-backed programs such as ABB’s PoP and refurbished services, or tested parts from specialists like Classic Automation, provide a higher level of assurance. For noncritical applications, surplus can be appropriate when combined with careful derating, inspection, and burn-in testing.

Inverter Drive Systems’ experience with an obsolete ACS600 that cost more than twice the price of an ACS580 in cumulative repairs and downtime is a useful benchmark. When your total cost of repairs, standby plant, and lost production for an obsolete drive begins to approach or exceed the cost of a modern replacement, you are likely better off upgrading. ABB’s condition-based maintenance approach can help by identifying drives whose key components are nearing end-of-life, giving you a one to two-year window to schedule replacements rather than waiting for catastrophic failures.

ABB’s PoP and refurbished parts services provide tested components from known sources, processed in ISO 9001 repair centers and backed by defined warranties, including a two-year warranty and price match conditions for PoP parts in the US. Compared with unvetted surplus, that premium buys you traceability, alignment with ABB’s original specifications, and the ability to lean on ABB’s service infrastructure if problems arise. For most critical drives and for legacy platforms that underpin essential processes, those benefits justify the incremental cost.

Supporting obsolete ABB drives and sourcing legacy parts is ultimately a reliability decision wrapped in a procurement problem. The sources discussed here, from ABB’s own lifecycle programs to Inverter Drive Systems, Amikon, Classic Automation, MB Drive Services, and Technology.org, all point toward the same conclusion. The plants that win are the ones that pair disciplined sourcing and testing with simple architectures and data-driven maintenance, treating every obsolete drive not as a future surprise but as an asset with a clear plan for its remaining life.

Leave Your Comment