-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When an ABB variable frequency drive suddenly refuses to run a motor, most plants see it as a ŌĆ£drive problem.ŌĆØ In the field, it is rarely that simple. ABB drives sit in the middle of a motor-drive-load system, and any weakness in power quality, wiring, the motor, the mechanics, or maintenance practices can surface as a drive fault or a silent, dead keypad.

As a power system specialist focused on reliability, I see the same pattern in facilities again and again. Teams rush to reset the drive or swap hardware, only to have the new unit fail for the same reason. The real payoff comes from treating ŌĆ£ABB drive not workingŌĆØ as the starting point for system-level failure analysis, not the conclusion.

This article walks through how to analyze those failures in a structured way, using patterns documented by sources such as Breaker Hunters, Fluke, Advanced Energy, and others. The principles apply across ABB ACS drives and similar industrial drives from other major vendors, but the focus here is on what you should look for around an ABB drive, how to interpret symptoms, and how to prevent repeat failures.

ABB, Siemens, Delta, Yaskawa, Mitsubishi, Danfoss, Schneider Electric, Lenze, AllenŌĆæBradley, and Fanuc all ship sophisticated drives that perform broadly similar functions. As Elkatek explains, a modern motor drive typically receives grid power, conditions it using rectifiers, DC bus capacitors, and pulse width modulation, then delivers optimized voltage and frequency to the motor.

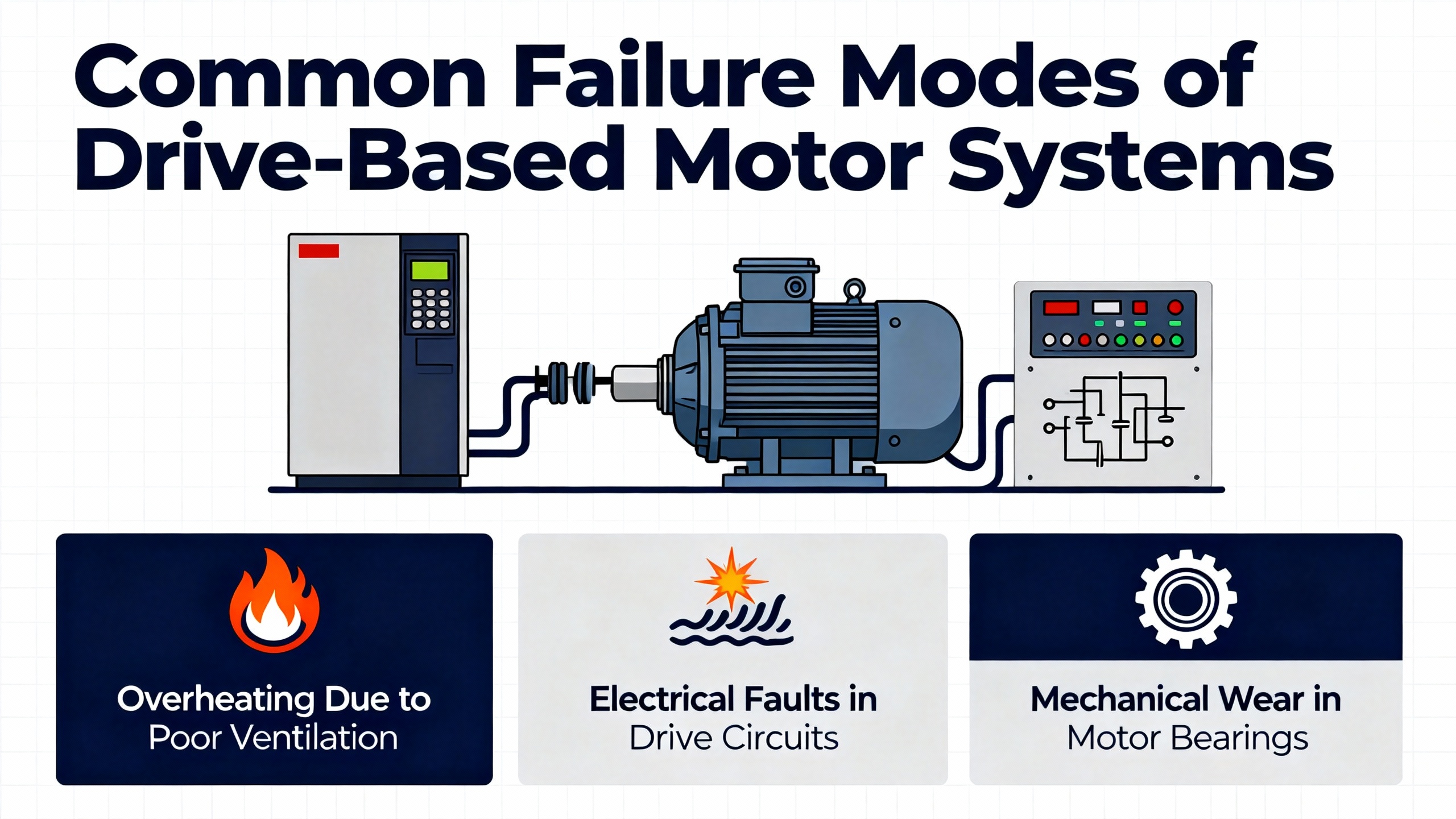

From a failure-analysis standpoint, it helps to think in terms of five blocks rather than one device.

The first block is the incoming power system: utility supply, upstream breakers and fuses, contactors, and grounding. Fluke and Breaker Hunters both highlight how transients, voltage imbalance, and harmonics originating here quietly erode motor and drive insulation long before the first trip occurs.

The second block is the drive itself. Inside an ABB drive you have input rectifiers, DC link capacitors and reactors, IGBT power modules, control boards, gate drivers, fans, and protective electronics. Elkatek calls out aging capacitors, IGBT failures, and fan breakdowns as common crossŌĆæbrand failure modes.

The third block is the motor. Studies summarized by Duke Electric and Fluke show that bearing issues and winding insulation breakdown dominate motor failures, with some sources attributing roughly half of motor failures to bearings and about thirty percent to overloading.

The fourth block is the mechanical load: pumps, fans, conveyors, extruders, and other driven equipment. Mechanical jams, misalignment, and changes in process conditions all show up electrically at the drive as rising current, thermal stress, and nuisance trips.

The fifth block is the control and feedback system: PLCs, field I/O, safety relays, encoders, and communication links. Articles from Digikey and Global Electronic Services show that misapplied parameters, communication faults, and feedback wiring problems are a major source of ŌĆ£mysteriousŌĆØ drive failures, especially in servo and smart-drive applications.

When an ABB drive ŌĆ£does not work,ŌĆØ failure analysis needs to consider all five blocks. The next sections outline how to do that without guesswork.

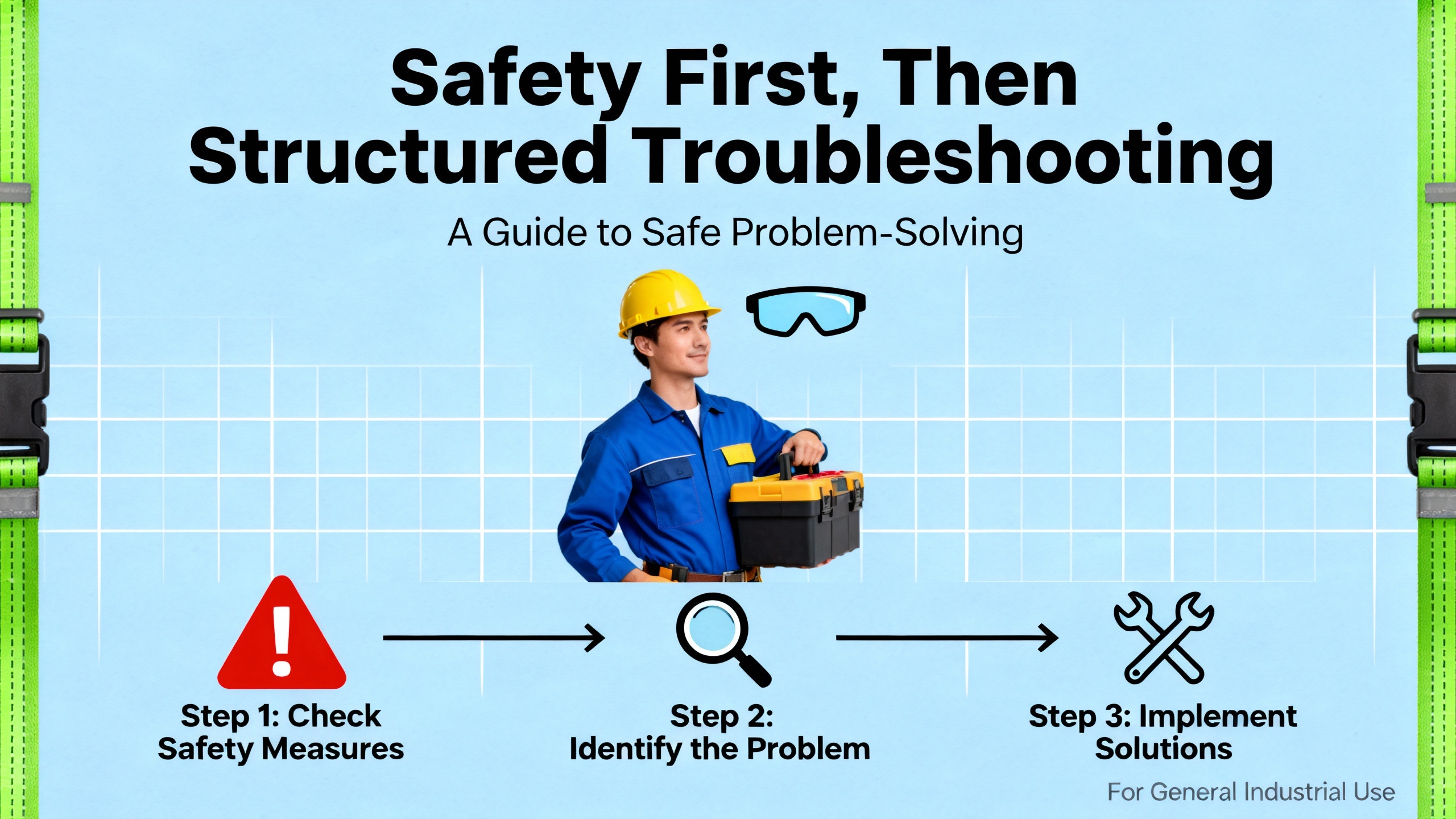

Work inside a live drive cabinet or motor control center exposes you to arc flash, shock, and mechanical hazards. Darwin Motion, Digikey, and Sure Controls all emphasize that safety and process discipline are nonŌĆænegotiable.

Before you touch an ABB drive that is not working, follow lockoutŌĆætagout procedures, comply with OSHA and company rules, wear appropriate PPE, and treat every open panel as if it contains lethal voltages. Remove conductive jewelry, control loose clothing, and, whenever possible, work with a partner rather than alone.

On the process side, DigikeyŌĆÖs discussion of the Navy sixŌĆæstep troubleshooting method and Duke ElectricŌĆÖs focus on root cause failure analysis both make the same point: follow a repeatable method. Do not jump straight to the latest alarm or the most convenient part to replace. Start with symptom recognition and elaboration, list likely faulty functions, localize the problem, then analyze the real failure mechanism.

In practice, that means that when an ABB drive is down, you begin with three kinds of information: what operators saw, what the drive reports, and what the system is doing mechanically and electrically.

Industrial Automation Co. stresses that ŌĆ£drive faultŌĆØ is not a useful symptom. The difference between a single overload trip in the middle of a production surge and a dead panel with no LEDs is enormous.

Useful symptom capture for an ABB drive includes the exact wording or code of any alarm, whether it appears instantly or after some run time, whether the motor fails to start, starts and then trips, jitters, runs at the wrong speed, or stops in the middle of a cycle, and whether there are sensory clues such as hot smells, visible damage, smoke, or unusual mechanical noise.

Record the drive model, any codes, and the operating context. Sure Controls recommends asking operators and mechanics when the problem first appeared, what changed recently, whether any wiring or equipment was modified, and whether the failure is intermittent or consistent. This basic factŌĆæfinding is cheap and often reveals a mechanical jam, a process change, or a past ŌĆ£temporaryŌĆØ wiring fix that never got documented.

Modern drives, including ABB ACS series units, are selfŌĆædiagnostic. They report overvoltage, undervoltage, overload, ground fault, overtemperature, and many other conditions. Global Electronic Services points out that drives from different brands may encode these as abbreviations such as overvoltage and undervoltage faults, overload alarms, and communication errors, but in every case the name of the fault tells you which part of the system is stressed.

Industrial Automation Co. shows how servo drives often log fault histories. ABB drives do the same. Reviewing the last several events and their timestamps can reveal patterns: trips that only occur during deceleration, faults that line up with thunderstorms or large load starts, or alarms that always appear at high ambient temperatures. That history is gold for failure analysis.

At the same time, Digikey warns against overŌĆæreliance on diagnostic LEDs and logs. An alarm code still has to be interpreted in context, using electrical measurements, mechanical checks, and an understanding of the process. Treat codes as clues, not the final answer.

Across brands and sectors, the same few failure modes show up repeatedly. The research notes below, drawn from Breaker Hunters, Fluke, Elkatek, Advanced Energy, and others, map closely to what turns up behind ABB drive failures in the field.

Breaker Hunters cites overheating from overload as a leading cause of motor control failure, estimating that roughly thirty percent of motor failures trace back to overloading. Fluke aligns with this, listing operational overload as a major contributor to motor damage.

An ABB drive that trips on overload or overcurrent is usually telling the truth. The driveŌĆÖs internal protection detects that the motor current exceeds its configured limits. That may happen because the process load has increased, a pump is partially blocked, a conveyor is jammed, a compressor is running at higher pressure, or someone has repurposed a motor and drive for a heavier task than they were selected for.

High ambient temperature and poor ventilation compound the problem. Breaker Hunters notes that dust buildup and tight installation spaces trap heat around motors; Elkatek and several motor maintenance sources report that clogged drive fans, dirty heat sinks, and inadequate cabinet ventilation push internal components beyond their design temperature.

In ABB drive investigations, some of the most common patterns are motors running consistently above their nameplate current, drives mounted in small, hot enclosures with no active cooling, and overload relays or electronic limits set well above the motorŌĆÖs fullŌĆæload amps ŌĆ£for extra margin.ŌĆØ Those choices can make an overload fault look like a nuisance, when it is actually the last line of defense before insulation damage.

Breaker Hunters describes how lightning, utility switching, and large equipment cycling cause transient overvoltages that last microseconds but can exceed insulation ratings. Fluke echoes this, noting that transient overvoltages slowly erode motor insulation and can precipitate early failure. Elkatek highlights that the same events stress drive input circuitry, particularly rectifiers and DC bus components.

On the other end of the spectrum, undervoltage sags prevent drives from supplying adequate voltage to the motor. Global Electronic Services explains that undervoltage faults force motors to draw higher current to maintain torque, which overheats windings. IEN and Fluke both recommend logging input voltage with a power quality analyzer to spot sags and swells rather than trusting spot checks.

In ABB systems, a drive that occasionally trips on overvoltage or undervoltage during storms or when large motors, welders, or capacitor banks switch is often the ŌĆ£canary in the coal mineŌĆØ for broader power quality issues. Adding surge protective devices, ensuring lowŌĆæimpedance grounding and bonding, and using line reactors or isolation transformers where recommended are not luxuries; they are preventive measures to protect both drives and motors.

ThreeŌĆæphase ABB drives are designed for balanced input and, where they output threeŌĆæphase power, for balanced loading across phases. Breaker Hunters and Fluke point out that even a few percent of voltage imbalance can generate six to fifteen times as much current imbalance, accelerating heating and insulation breakdown.

Phase imbalance can come from uneven singleŌĆæphase loading in the plant, long feeders with unequal impedance, a failing capacitor in a powerŌĆæfactor correction bank, or something as mundane as a loose termination on one phase of a breaker or contactor. Single phasing is the extreme case where one phase is lost altogether because a fuse blew, a contact failed, or a conductor opened.

Breaker Hunters notes that motors under these conditions may hum, vibrate, and run with reduced torque before tripping overloads. Fluke and IEN recommend measuring phaseŌĆætoŌĆæphase voltages at both the ASD supply and the motor, using motor drive analyzers to identify even small deviations, and ensuring that phase current imbalance remains well under ten percent.

ABB phase monitor relays, correctly applied, can detect missing phase and severe imbalance and shut the system down before damage occurs. But the underlying cause is still a connection, loading, or supply issue that needs correction.

Modern facilities pack many nonŌĆælinear loads into the same distribution system. Breaker Hunters names VFDs, UPS systems, and LED lighting as common sources of harmonics; Fluke describes harmonics as unwanted higherŌĆæfrequency voltage and current components riding on the fundamental waveform.

These harmonic currents do not produce torque. Instead, they circulate in motor windings, transformers, and buswork, causing extra heating and sometimes audible noise or vibration. Fluke references standards such as IEEE 519 that define acceptable limits for total harmonic distortion; when those limits are exceeded, nuisance tripping and thermal stress become frequent visitors.

For ABB drive systems, high harmonic distortion may appear as unexplained motor heating even at normal loading, intermittent drive trips, or problems with sensitive control electronics. Breaker Hunters and Fluke both recommend measuring THD with appropriate analyzers, installing line reactors or passive or active harmonic filters, and, for larger systems, considering multiŌĆæpulse drive configurations and properly sized neutrals.

Elkatek and Breaker Hunters describe common VFD failures that apply across brands: contamination from dust, oil, and moisture; undersized drives forced to run near or above rating; failed cooling fans; aged electrolytic capacitors; and stressed IGBT modules.

Variable frequency drives contain components with finite lifespans. VFD cooling fans and DC bus capacitors gradually degrade, especially in hot environments. Elkatek notes that capacitor aging and fan failures are among the leading internal hardware issues. Power surges and transients can blow input rectifiers or output stages. Over time, repeated thermal cycling and vibration can crack solder joints or damage circuit boards.

Industrial Automation Co. shows in detail how servo drives with internal power board failures may present as ŌĆ£no displayŌĆØ conditions or persistent hardware alarms. In ABB drives, analogous symptoms include dark keypads despite correct input voltage, repeated hardware fault codes after powerŌĆæup, visible damage on boards, or a burnt electronics odor.

The fix can range from cleaning and restoring airflow to full board or drive replacement. Elkatek emphasizes the importance of brandŌĆæspecific expertise, original or equivalent highŌĆægrade spare parts, and thorough postŌĆærepair testing rather than adŌĆæhoc component swapping.

Modern ABB drives are almost never standŌĆæalone. They integrate with PLCs, safety systems, fieldbuses, and speed or position feedback devices. Global Electronic Services points out that communication faults, parameter resets, and incorrect protocol settings are common in smart drives. Industrial Automation Co. shows how encoder errors, open feedback circuits, and wrong parameter sets cause servo drives to shut down even when power hardware is healthy.

In ABB installations, symptoms such as drives that will not start despite healthy power, ŌĆ£runŌĆØ commands that do nothing, or intermittent trips tied to network activity often trace back to control logic or communication issues. Misconfigured start sources, mismatched baud rates or node addresses, altered safety interlock wiring, or failing encoders can all make a good drive look bad.

Digikey warns that diagnostics and LEDs can be misleading if you do not understand the timing of the machine. Watching I/O, relays, and drive status through a complete cycle, with reference to schematics, often reveals that a missing start signal or open safety contact, not the drive, is the root of ŌĆ£drive not working.ŌĆØ

Many ABB drive fault logs ultimately lead back to the motor or the mechanics. Hesco, GES Repair, Groschopp, Precision Zone, and others all show that bearing failures, winding deterioration, insulation breakdown, and mechanical misalignment are at the core of most motor failures.

Duke Electric reports that bearing problems account for more than half of motor failures in some analyses. Fluke notes that about thirteen percent of motor failures and over sixty percent of mechanical failures in industrial plants involve bearings. Winding problems present as overheating, imbalance in resistance readings, or insulation resistance that has fallen below acceptable levels.

From the driveŌĆÖs perspective, these issues surface as overload trips, overcurrent alarms, ground faults, and rising current draw over time. IEN and Sure Controls highlight that current imbalance, excessive vibration, and rising thermal measurements are early warnings that the motor, not the drive, is deteriorating.

Mechanical issues in the driven load can have the same effect. Groschopp describes how tight belt tension, blocked fan housings, or mechanical jams raise torque demand, causing motors to slow, heat up, or stall. IEN distinguishes between variable torque loads, which rarely overload drives unless impeded, and constant torque loads, which can demand high current at low speed and may require external cooling.

Breakers Hunters devotes an entire section to poor maintenance and environmental factors. Dust, moisture, corrosive vapors, and vibration gradually undermine otherwise good equipment. Motors and ABB drives installed in sawmills, water treatment plants, or outdoor enclosures face extreme contamination and temperature swings.

Advanced Energy notes that electric motor systems consume more than forty percent of global electricity and that only a tiny fraction of lifecycle cost comes from purchase price; most cost lies in energy and downtime. That makes the case for formal motor management and preventive maintenance programs compelling.

GES Repair and Valley Power Systems both stress cleanliness, correct lubrication, and performance monitoring. Layers of dust on motors and drives act as insulation and clog ventilation paths, raising operating temperatures. Moisture and corrosive atmospheres corrode terminals and circuit boards, increasing resistance and causing intermittent faults. Vibration loosens terminals and components over time.

Breaker Hunters, Hesco, and Advanced Energy all recommend regular inspections, tightening of electrical connections, cleaning of motors and control panels, appropriate choice of enclosures and antiŌĆæcondensation heaters in harsh environments, and using tools such as infrared cameras and vibration analysis to detect developing issues before failure.

When an ABB drive is not working, a structured workflow lets you move from symptom to cause without unnecessary part chasing. The steps below synthesize guidance from Digikey, Sure Controls, DavisŌĆæStandard, Groschopp, Monolithic Power, Fluke, and others.

The first step is always safety and documentation. Lock out and tag out the system, verify absence of voltage where required, and review the latest service logs, operating history, and any changes since the last time the system ran reliably. Digikey strongly encourages written logs and standard operating procedures because intermittent or temperatureŌĆædependent faults often span multiple shifts and technicians.

Next, stabilize and elaborate the symptom. Run the machine, if safe, through a complete cycle and observe exactly when and how the ABB drive misbehaves. Note whether faults appear at start, during acceleration, at constant speed, during deceleration, or randomly. Monolithic Power emphasizes the importance of observing noise, heat, vibration, and odors as integral diagnostic clues.

Then, verify the power supply. Sure Controls and Groschopp both recommend confirming correct line voltage at the drive terminals, checking for tripped fuses or breakers, and inspecting visible terminations for discoloration, melted insulation, or looseness. Fluke suggests using power quality analyzers to measure voltage imbalance, sags, swells, and harmonics at both the line side and the drive input rather than relying on spot readings.

Once input power is confirmed, separate electrical from mechanical causes. DavisŌĆæStandard describes a simple method to distinguish mechanical from electrical noise by running a motor at fixed speed and then removing power; noise that decays with speed points to mechanical issues, while noise that disappears abruptly is more likely electrical. Precision Zone and Industrial Automation Co. recommend swapping in a knownŌĆægood motor or testing the motor independently with insulation resistance and resistance measurements to see whether the fault follows the motor or stays with the drive.

After that, examine the mechanical load. IEN and Groschopp advise checking couplings, belts, screws, and driven equipment for binding, misalignment, and process conditions that increase torque demand, such as thicker material, lower barrel temperatures in extrusion, or valves that no longer fully open. Overload faults that coincide with process changes almost always have a mechanical or process root cause.

Now look closely at the drive and control system. A visual inspection, as recommended by Elkatek, Sure Controls, and Industrial Automation Co., should check for dust and debris inside the ABB drive, failed or blocked fans, signs of overheating or arcing, and loose connectors. At the same time, verify control inputs: ensure that start commands actually reach the drive, that all safety and auxiliary inputs are in the expected states, and that network or fieldbus communications are healthy.

Only after these blocks have been evaluated should you dig into deeper diagnostics such as THD measurements, shaft voltage checks, or detailed waveform analysis, as suggested by Fluke and IEN. At this stage, you may be confirming a suspected harmonic issue, a degraded DC link capacitor bank, or bearing currents in large motors.

Finally, perform root cause failure analysis rather than stopping at the first failed part. Duke ElectricŌĆÖs discussion of the fiveŌĆæWhys technique is very applicable here. If an ABB driveŌĆÖs IGBT module failed, ask why it was overstressed. Was the motor cable length and filtering appropriate, or were there repeated overvoltage events from a regenerative load without proper braking? If a motor bearing failed, was it a lubrication issue, a shaft voltage problem, or misalignment induced by soft foot? Each ŌĆ£whyŌĆØ gets you closer to a corrective action that prevents recurrence.

The table below summarizes how some common ABB drive symptoms map to likely areas and first checks, based on patterns described in the research notes.

| Symptom from ABB drive system | Likely area to investigate first | Typical root causes discussed in research notes | First diagnostic steps that add the most insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated overload or overcurrent trips under load | Motor and mechanical load | Mechanical jam, increased process torque, undersized motor or drive, poor ventilation causing overheating | Compare measured current to motor nameplate, inspect load for obstruction or changes, check motor and drive cooling paths |

| Occasional overvoltage or undervoltage faults, especially during storms or large load switching | Incoming power and grounding | Utility or internal transients, voltage sags from large starts, inadequate surge protection, weak grounding | Log line voltage with a power quality analyzer, inspect and test surge protective devices, verify grounding and bonding integrity |

| Motor hums or fails to accelerate, drive trips quickly, phases show unequal currents | Phase balance and connections | Voltage imbalance from uneven loading, loose terminations, blown fuse, single phasing | Measure phaseŌĆætoŌĆæphase voltages and currents at drive and motor, inspect terminations and fuses, check for dropped phase |

| Motor and drive run hot even at moderate load, with occasional nuisance trips | Harmonics, overload, and cooling | High THD from nonŌĆælinear loads, continuous operation near or above rating, blocked filters, fan failures | Measure THD, inspect drive fans and filters, confirm drive sizing against application duty, verify ventilation and ambient temperature |

| Drive display dark despite apparent line voltage, or persistent hardware fault codes at powerŌĆæup | Internal drive hardware | Aged capacitors, failed rectifiers or IGBTs, damaged control boards from surges, severe contamination | Verify input voltage at drive terminals, perform visual inspection for damage and contamination, consult ABB diagnostics and consider specialized drive repair |

| Drive reports communication or feedback fault, will not start or stops erratically | Control circuits and feedback devices | Wrong or reset parameters, cabling faults, encoder failure, network configuration errors | Verify start/stop logic, check communication settings and cabling, test or swap feedback devices, review parameter sets against design |

This kind of mapping helps teams move away from random part replacement toward evidenceŌĆædriven fault localization.

Failure analysis is only complete when it feeds back into design, maintenance, and operating practices. Advanced EnergyŌĆÖs motor management guidance is blunt: since ninetyŌĆæplus percent of motor lifecycle cost is in electricity, not purchase price, small improvements in reliability and efficiency pay off significantly in energy and downtime savings.

Correct sizing and selection are the first line of prevention. Advanced Energy recommends running motors in the seventyŌĆæfive to one hundred percent load range for best efficiency and life. Invention HouseŌĆÖs VFD troubleshooting guidance adds that misŌĆæmatched motors and drives are a frequent cause of repeated failures and burned motors. For ABB systems, that means selecting drives with appropriate current ratings and duty class, matching motor insulation and construction to inverter duty where required, and ensuring that applicationŌĆæspecific stresses such as heavy starting or frequent cycling are accounted for.

Power quality management is equally important. Breaker Hunters and Fluke emphasize the longŌĆæterm damage caused by transients, voltage imbalance, and harmonics. Installing surge protection at service entrances and critical motor control centers, using line reactors or harmonic filters where THD is high, and periodically auditing power quality, especially after adding large drives or capacitor banks, all reduce stress on ABB drives and connected motors.

Preventive maintenance on both drives and motors cannot be a vague intention. GES Repair, Valley Power Systems, and Hesco all recommend formal programs that include cleaning enclosures and motors, checking and tightening terminals on a scheduled basis, inspecting and replacing drive fans and filters, monitoring motor vibration and temperature, and logging key operating parameters. Industrial Automation Co. and Fluke both show how realŌĆætime and trending data from modern drives and sensors enable predictive maintenance, catching deviations weeks or months before failure.

Environmental control is another overlooked factor. Breaker Hunters points out how dust and moisture in sawmills, water plants, and outdoor installations turn otherwise sound equipment into failureŌĆæprone systems. Selecting appropriate NEMA enclosures, adding antiŌĆæcondensation heaters in panels, maintaining room temperatures within equipment specifications, and controlling humidity and dust levels in electrical rooms all extend ABB drive and motor life.

Finally, documentation and training close the loop. Digikey recommends detailed service logs and standard operating procedures for troubleshooting, while Fluke encourages careful documentation of baseline conditions and tolerances. Training technicians in systematic methods, safe measurement techniques, and the specific features of ABB drives avoids both unsafe practices and expensive misdiagnoses.

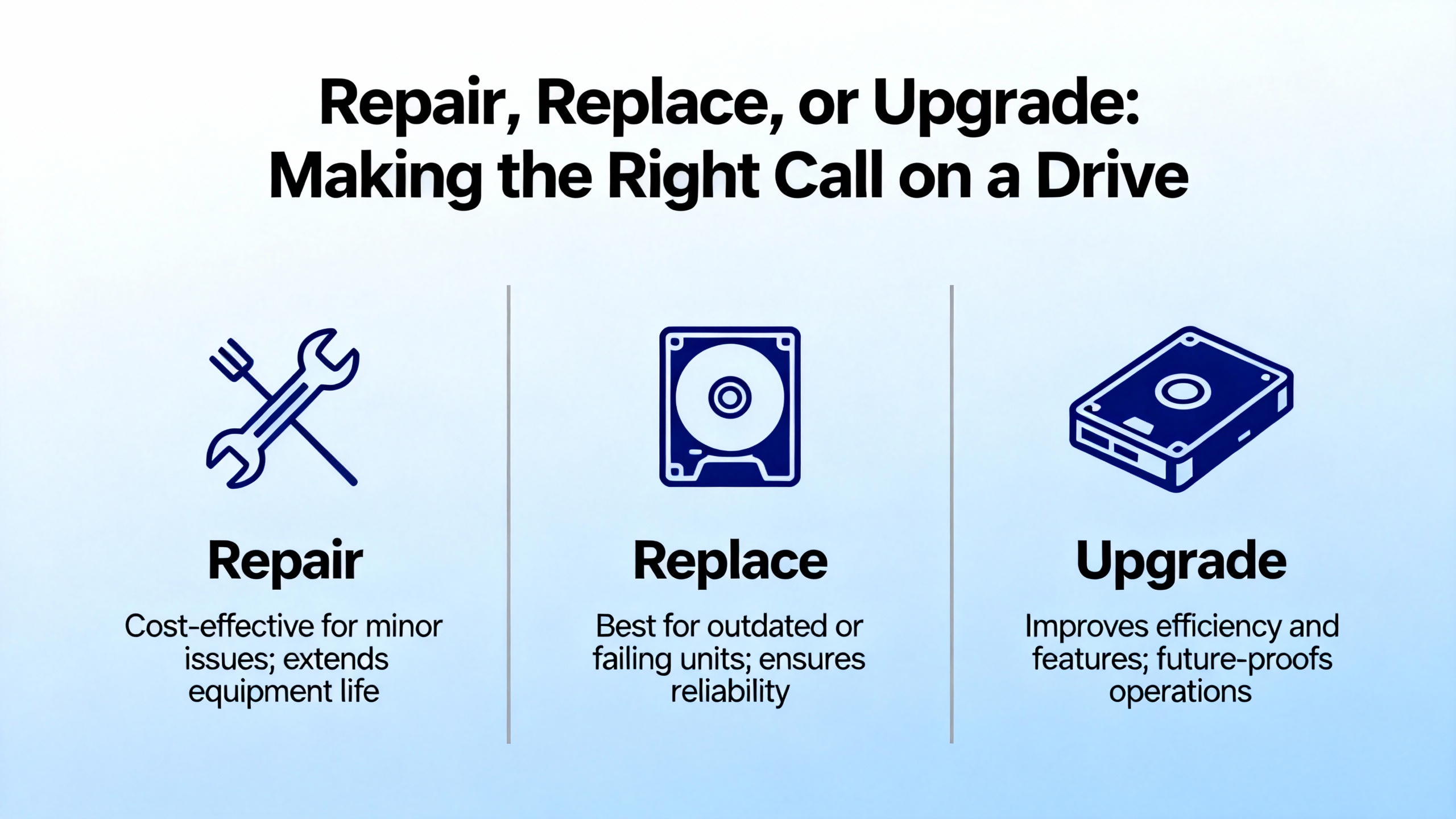

Industrial Automation Co. describes a decision framework for servo drives that applies neatly to ABB VFDs. Repair makes sense when the issue is clearly internal to the drive, the model is costly or difficult to replace, preserving original settings and wiring has value, and you can tolerate the repair lead time. Elkatek stresses that highŌĆæquality repair should involve brandŌĆæspecific expertise, proper test infrastructure, and meaningful warranties.

Replacement, on the other hand, is justified when the same fault has occurred multiple times, visible board damage suggests widespread stress, the drive is old enough that key components such as capacitors are near end of life, or downtime costs demand immediate recovery with an inŌĆæstock unit rather than waiting for repair. Replacement is also an opportunity to upgrade to a newer ABB drive with better diagnostics, energyŌĆæsaving features, or builtŌĆæin connectivity that supports predictive maintenance.

Retaining the existing drive but making no change is rarely the right answer after a serious failure. Even when a quick reset gets you running, the failure analysis work described earlier should still be completed. Root causes such as overload, imbalance, harmonics, contamination, or control logic problems do not disappear on their own. Addressing them is what differentiates a reliable plant from one that lives in a cycle of repeated ABB drive ŌĆ£mysteryŌĆØ failures.

Start with safety, then gather information. Confirm that line power is present at the drive, check for obvious wiring damage or loose terminations, and read any fault codes or messages. Talk with operators about when the issue began and what changed. As Sure Controls, Digikey, and Monolithic Power all suggest, simple observations and basic electrical checks resolve many problems before you ever need to open the drive.

Look for patterns. If the drive powers up normally but trips on overload or overcurrent under mechanical load, focus first on the motor and process: measure current versus nameplate, inspect for jams or misalignment, and check vibration and temperature. If the drive shows hardware faults at powerŌĆæup, has no display despite correct input voltage, or smells burnt, internal drive hardware is suspect. Techniques described by DavisŌĆæStandard, Precision Zone, and Industrial Automation Co., such as temporarily swapping in a knownŌĆægood motor or testing the motor independently, can help you see whether the fault follows the motor or stays with the drive.

There is no single interval that fits every plant, but the sources summarized here suggest at least annual basic inspections for motors and control panels in normal environments, and more frequent checks in harsh, hot, or dirty areas or for critical equipment that runs continuously. Advanced Energy, Valley Power Systems, and GES Repair all advocate scheduled programs that include cleaning, tightening, lubrication where applicable, verification of protective device settings, and periodic use of tools such as infrared cameras and vibration analysis for highŌĆæduty or critical assets.

ABB drives are robust pieces of equipment, but they are only as reliable as the power they receive, the motors and mechanics they control, and the maintenance culture that surrounds them. Treat each ŌĆ£drive not workingŌĆØ event as an opportunity to understand and strengthen the entire motorŌĆædrive system, and your plant will see fewer surprises, longer equipment life, and far more predictable uptime.

Leave Your Comment