-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When you design or upgrade a critical power system today, the technical challenge is only half the battle. The other half is time. The lead time for ABB distributed control system (DCS) components can easily determine whether your UPS-backed switchgear, inverters, and process loads start up on time or spend their first year as an expensive construction site.

Across the supply chain, industrial hardware lead times have lengthened and become less predictable. Demand Driven Technologies reports that some electronic components moved from roughly three to four months of lead time to as long as one to two years. MRPeasyŌĆÖs manufacturing research notes that average raw material delivery times stretched from 65 days to 81 days, while supply disruptions now cost manufacturers about eight percent of annual revenue. In that context, treating ABB DCS hardware as ŌĆ£off-the-shelfŌĆØ is no longer realistic.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs perspective, the DCS is part of the power protection system. If you lose a controller or a highŌĆæintegrity I/O card, the most robust UPS scheme in the world cannot save you from an unplanned outage. The way you plan lead time for ABB DCS components needs to reflect that reality.

This article walks through how lead time works for ABB-based control systems, why it has become so volatile, and how to plan automation projects so that control hardware does not become the critical path on your power infrastructure.

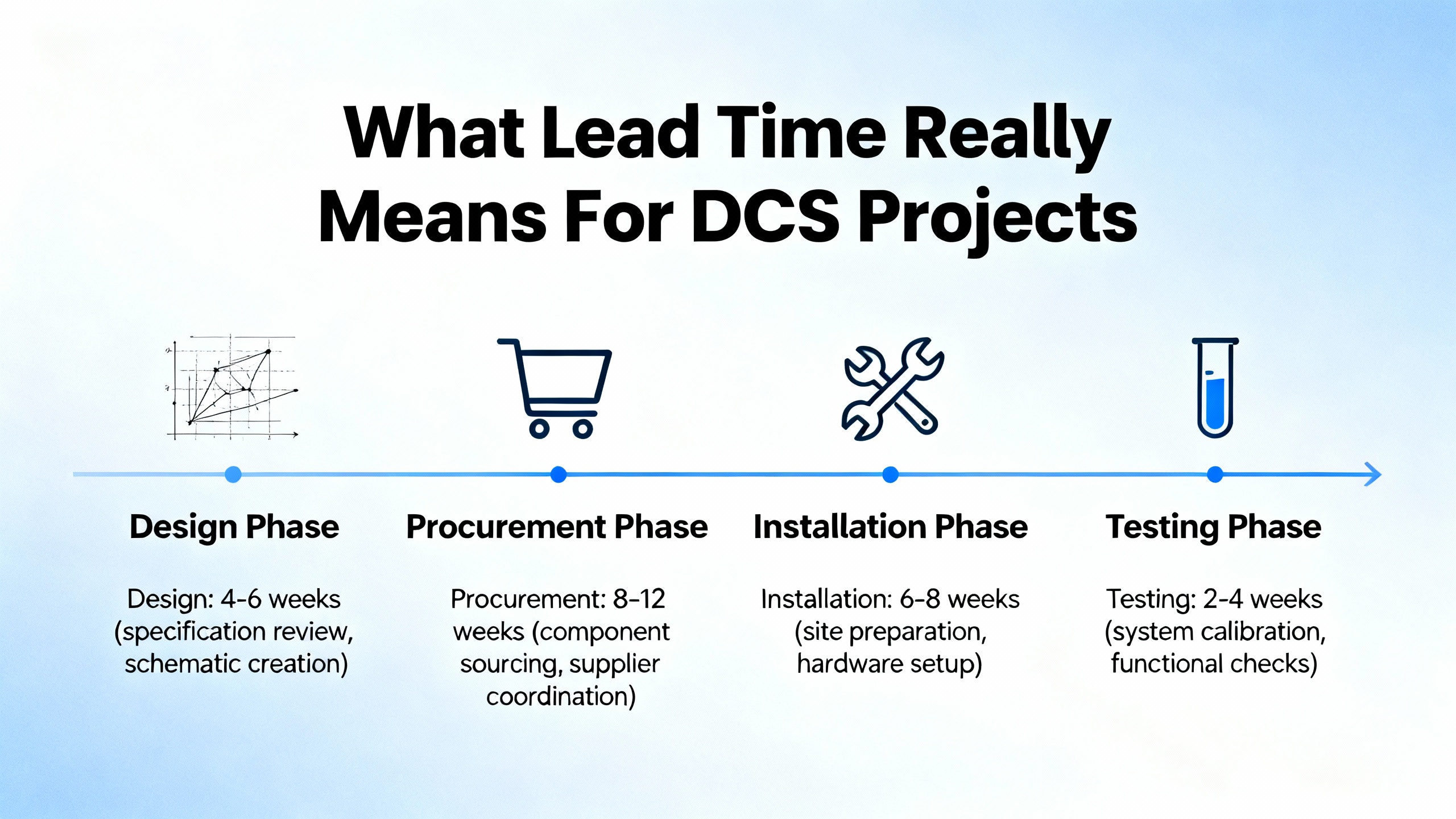

Supply chain experts like Anvyl and Ramp define lead time as the total elapsed time from initiating a request until the goods are received and ready to use. That is broader than ŌĆ£shipping timeŌĆØ or ŌĆ£manufacturing time.ŌĆØ Ramp breaks procurement lead time into three segments: preŌĆæprocessing, processing, and postŌĆæprocessing. That structure maps well onto ABB DCS hardware.

PreŌĆæprocessing covers everything that happens before the order hits ABBŌĆÖs factory or your local ABB partner. In a DCS context, that includes system scoping, I/O count estimates, controller and cabinet selection, internal approvals, and often contract negotiations. It is common for weeks to pass in this phase, even before a purchase order number exists.

Processing covers order placement, ABBŌĆÖs confirmation, and actual manufacturing or configuration of the equipment. For modular systems like ABB System 800xA, this can involve assembling racks of AC 800M controllers, configuring S800 or Select I/O modules, loading firmware, and building preŌĆæconfigured cabinets. This stage typically dominates the lead time clock for new hardware.

PostŌĆæprocessing includes shipping, customs when applicable, onŌĆæsite receiving and inspection, plus any staging or factory acceptance testing. In power projects, this postŌĆæprocessing phase often overlaps with electrical room buildŌĆæout and cable installation. Delays here are just as real as any delay in the factory.

From the projectŌĆÖs point of view, what really matters is endŌĆætoŌĆæend lead time: the time from when you decide you need an ABB controller, I/O rack, or network module until that component is bolted into a panel, powered from your UPS, and ready for I/O checkout. That is the number that should appear in your integrated schedule, not just the quoted ŌĆ£exŌĆæworksŌĆØ lead time.

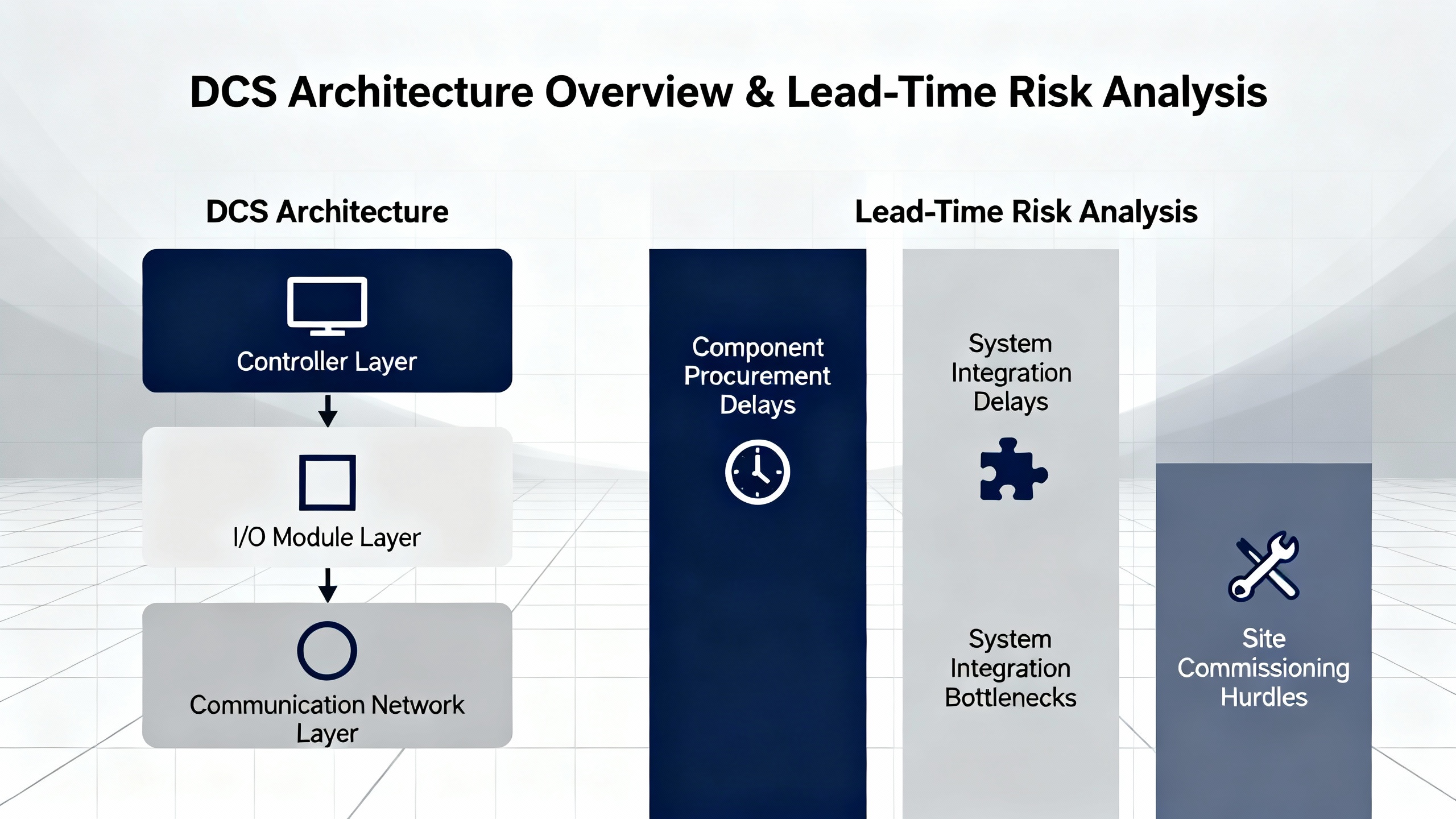

Tomarok EngineeringŌĆÖs overview of ABB automation systems describes ABBŌĆÖs DCS platforms as plantŌĆæwide automation solutions that unify engineering, operations, safety, and power automation. System 800xA can integrate a wide range of controller families, including AC 800M and several legacy lines, while communicating with over four hundred types of control devices and networks through PLC Connect. ABBŌĆÖs I/O families such as S800 I/O, S900 I/O, and Select I/O offer modular, fieldŌĆæmountable, and safetyŌĆærated options, with features like hotŌĆæswap and redundancy to reduce downtime.

Those same strengths create a complex bill of materials. A typical ABB DCS in a power application combines controllers, distributed I/O, highŌĆæintegrity safety I/O, communication modules, network infrastructure, and interfaces to UPS, inverters, and switchgear. Each group behaves differently from a leadŌĆætime perspective.

A simple way to look at the risk is to group components by function and supplyŌĆæchain exposure.

| Component group | Examples in ABB ecosystem (per Tomarok and ABB partner material) | Typical supplyŌĆæchain sensitivity | Failure or delay impact in power systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controllers and CPUs | AC 800M and related controller families | Dense in specialized electronics and firmware; strongly affected by global semiconductor lead times | Loss of a primary or redundant CPU can stop process and power automation, including UPS and transfer logic |

| Remote and safety I/O | S800 I/O, S900 I/O, Select I/O, SIL3 highŌĆæintegrity I/O | Mix of commodity and specialized components; safetyŌĆærated modules often have fewer alternative sources | Missing or failed I/O prevents healthy feedback from switchgear, breakers, battery systems, and protective relays |

| Communication gateways and protocol modules | Interfaces for PROFIBUS, MODBUS, Ethernet/IP, IEC 61850, FOUNDATION Fieldbus, OPC UA | Dependent on both ABB firmware and fieldbus chipsets; sensitive to electronics shortages | Loss affects integration with drives, relays, and thirdŌĆæparty PLCs, undermining selectivity schemes and monitoring |

| Engineering and operator stations, servers, and historians | 800xA operator workplaces, engineering servers, archiving systems | Often built on more standard IT hardware; still subject to CPU, memory, and storage constraints | Impacts visibility and control; in worst cases forces manual operation during outages or transitions |

| I/O cabinets, marshalling, and power distribution inside panels | Cabinets, terminal blocks, internal power supplies, wiring harnesses | Many items are more commodityŌĆælike; cabinets and wiring materials are usually less volatile than electronics | Delays can still stall SAT and energization if panels cannot be fully assembled |

None of these categories lives in isolation. A DCS upgrade in a data center, for example, might depend on ABB controllers, Select I/O panels near switchgear, IEC 61850 gateways to protective relays, and redundant operator stations. If any of those groups has a materially longer lead time, the entire automation scope tends to shift to its schedule.

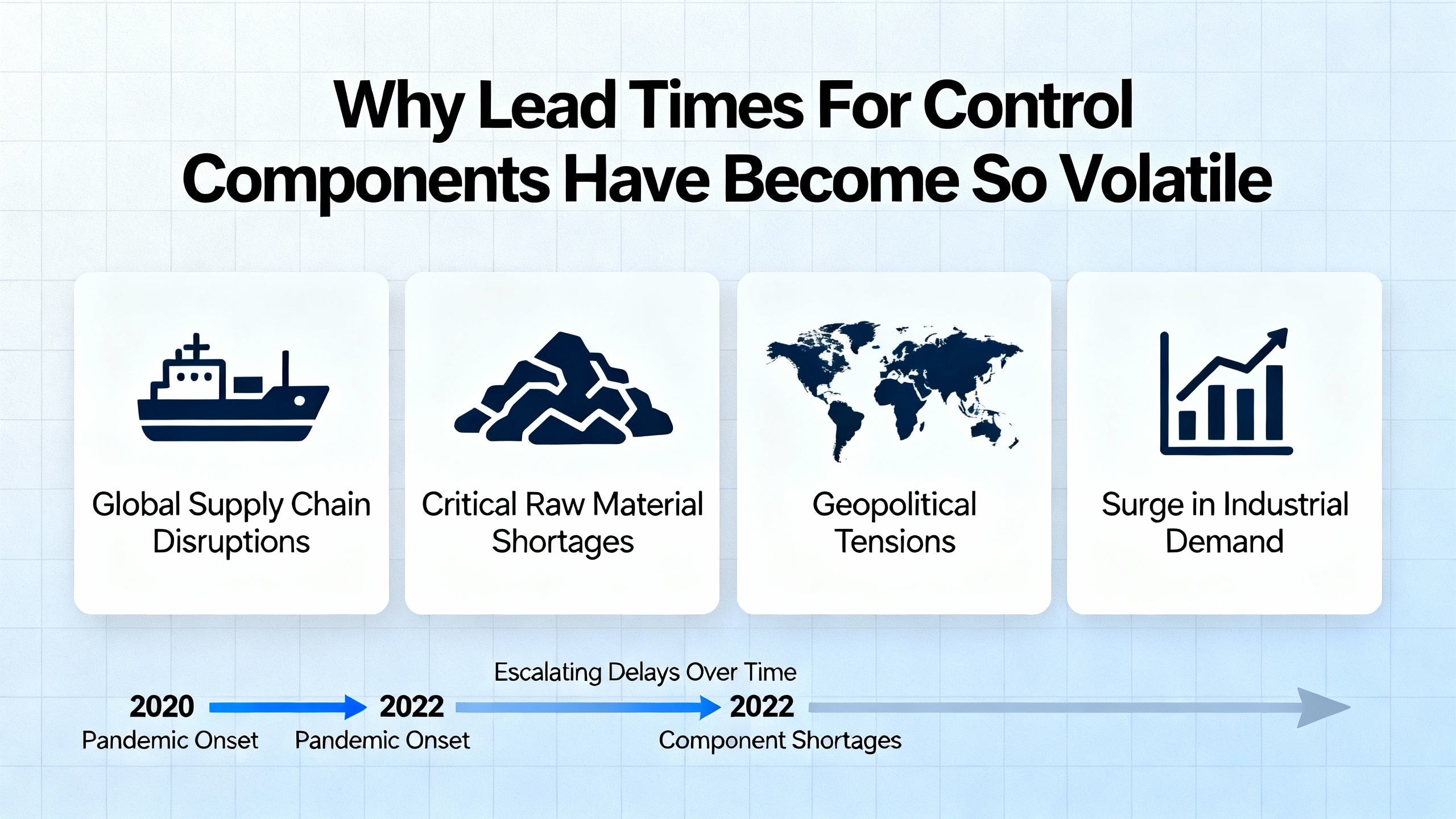

Several independent sources point to the same structural problem. Demand Driven Technologies notes that, after recent disruptions, lead times for some electronic components expanded from a typical three to four months out to as much as one to two years. MRPeasy reports that average raw material deliveries lengthened by about twentyŌĆæfive percent, from 65 to 81 days, and that supply disruptions now cost manufacturers around eight percent of annual revenue. Their data on electronic components shows lead times in the range of twelve to forty weeks for certain parts, with capacitors and automotive semiconductors cited as particularly long.

Those statistics do not come from ABB specifically, but a DCS controller or highŌĆæintegrity I/O card is built on the same global semiconductor and passive component supply chain. Even if ABB and its partners do an excellent job buffering risk, the underlying realities of chip and board manufacturing still apply.

On the heavy electrical side, Vizient highlights that lead times for large mechanical and electrical equipment in healthcare construction rose sharply as well. They cite generator lead times moving from roughly thirtyŌĆæfive to forty weeks to around sixtyŌĆæfive to seventyŌĆæfive weeks, and custom air handling units roughly doubling from about fifteen to thirty weeks between approval and delivery. That same macro environment affects mediumŌĆævoltage switchgear, UPS systems, and rectifierŌĆæcharger packages that sit adjacent to your DCS.

The takeaway is not that every ABB part will take a year to arrive. It is that your planning assumptions must acknowledge this volatility. Lead time is now a strategic design parameter, not just a line on a purchase order.

Project teams are often tempted to plug ŌĆ£catalogŌĆØ lead times into schedules and hope they remain valid. The leadŌĆætime research from Demand Driven Technologies and MRPeasy argues against that approach. They recommend working with pragmatic, relatively stable leadŌĆætime parameters in your systems and revisiting them on a monthly or quarterly cadence based on measured performance.

Applied to ABB DCS projects, that starts with building a realistic baseline rather than relying on optimistic quotes. During frontŌĆæend engineering, agree on working leadŌĆætime values for each component group, including controllers, different I/O families, communication modules, and panel fabrication. Use historical data from previous projects, your ABB partnerŌĆÖs experience, and recent purchase orders. Then lock those values into your integrated schedule and materials planning tools, understanding that any improvement later is upside rather than the assumption.

Another powerful step, drawn from valueŌĆæstream analysis guidance by visTABLE and demandŌĆædriven planning concepts, is to segment your DCS bill of materials by both criticality and lead time. Controllers, safety I/O, and key communication gateways almost always fall into the highŌĆæcriticality, longŌĆælead quadrant. Commodity items such as generic terminal blocks or cabinet accessories tend to sit in lowŌĆæcriticality, shorterŌĆælead quadrants. With that segmentation in hand, you can design decoupling points: for example, commit to controllers and safety I/O at a very early stage, while leaving some flexibility in the exact mix of nonŌĆæsafety I/O cards or cabinet layouts.

RampŌĆÖs framework of preŌĆæprocessing, processing, and postŌĆæprocessing time is helpful when deciding how early to commit. On many ABB projects, preŌĆæprocessing for longŌĆælead control components can safely start well before the rest of the plant design is frozen. You know that you will need a certain number of AC 800M controllers and a basic footprint of Select I/O regardless of minor I/O count swings. That allows you to negotiate frame agreements or release early purchase orders for the backbone hardware, while leaving the long tail of smaller items for a later wave.

Heavily standardized designs help here. Tomarok Engineering notes that 800xA provides a unified platform that can support multiple controller families, all tied into the same engineering environment. When an organization standardizes on a small set of ABB controller and I/O types across several plants, you gain volume leverage, simplify spares, and make leadŌĆætime planning more robust. GEP and other procurement experts argue that such standardization, tied to clear supplier performance expectations, tends to reduce total lifecycle cost and shorten effective lead times.

At the same time, supply chain research from Anvyl, Netstock, and Veridion shows the value of diversifying the supplier base where it makes sense. Anvyl reports that about seventyŌĆæone percent of brands already have multiple suppliers for the same item and that the same share plan to add more. For ABB DCS hardware, that does not mean switching to nonŌĆæABB substitutes, which would break your standardization. It typically means qualifying more than one authorized ABB channel partner or systems integrator, having framework agreements in place, and ensuring more than one physical path for delivery.

Logistics and proximity also matter. Several sources, including Plex (Rockwell Automation) and Veridion, emphasize using domestic or regional suppliers where feasible to cut shipping times and avoid customsŌĆærelated delays. For ABB projects, working with a local ABB partner such as Tomarok Engineering can reduce inŌĆætransit time for cabinets, make field engineering support more responsive, and simplify warranty exchanges, even if some components ultimately originate from global factories.

Finally, contracts should explicitly reflect leadŌĆætime expectations. Veridion, GEP, and Anvyl all recommend embedding leadŌĆætime commitments, penalties for chronic delays, and in some cases incentives for early delivery into supplier agreements. For ABB DCS channels, that might take the form of serviceŌĆælevel agreements with defined onŌĆætime delivery targets, clear communication obligations about expected delays, and escalation paths when a controller or I/O batch threatens to slip your energization date.

From a power system specialistŌĆÖs perspective, ABB DCS lead time can never be considered in isolation. It must be coordinated with the procurement and construction timelines for UPS systems, inverters, switchgear, generators, and protection relays.

The Vizient data on generator and air handling unit lead times illustrates how quickly powerŌĆærelated equipment can become the bottleneck. In a combined power and automation project, you might see mediumŌĆævoltage switchgear and generators ordered at the same time as DCS cabinets. If the control panels arrive months before the switchgear, your operator stations, controllers, and I/O sit idle, tying up capital while contributing nothing to schedule progress. If the situation is reversed and switchgear and UPS systems arrive before the DCS hardware that controls them, you cannot perform meaningful functional testing.

The practical answer is to build a single integrated procurement schedule for all critical power and control equipment. Use the same leadŌĆætime segmentation across UPS, inverters, switchgear, generators, ABB DCS hardware, and key network equipment. For each asset, identify whether lead time is driven more by manufacturing, shipping, or internal approvals. Then align early commitment points so that the most constrained items are ordered first, and dependent systems are synchronized.

This is also where good demand forecasting and crossŌĆæfunctional communication pay off. Plex and Anvyl both stress that sharing reasonably accurate forecasts with suppliers allows them to reserve capacity and raw materials. For multiŌĆæsite operators standardizing on ABB 800xA and common UPS architectures, that can translate into rolling annual forecasts of expected controller, I/O, and panel needs. The goal is to keep large, infrequent surprises out of the system.

Once the project is commissioned, the leadŌĆætime problem does not disappear. It simply changes shape, becoming a spares and lifecycle management problem.

Demand Driven Technologies and Netstock both highlight the importance of treating lead times as strategic parameters when sizing inventory buffers. In a DCS context, that means considering spare controllers, safety I/O modules, and key communication interfaces as inventory items just like UPS power modules or breaker trip units. Netstock presents an example where, for a simple item with known sales and lead time characteristics, a reorder point of 117 units arises from combining leadŌĆætime demand and safety stock. The exact numbers differ for ABB components, but the principle holds: longer and more variable lead times require higher safety stock if you want to protect service levels.

A pragmatic approach starts by deciding which ABB DCS components deserve true N+1 or N+2 redundancy on the shelf and which can tolerate a longer recovery. In many critical power applications, spare quantities for CPUs, highŌĆæintegrity I/O, and protocol gateways that connect to protection and UPS equipment are nonŌĆænegotiable. Less critical or more commodityŌĆælike items, such as certain cabinet accessories, might be managed with lower safety stock and a greater reliance on the supply chain.

The Demand Driven modelŌĆÖs distinction between a longŌĆæterm commitment horizon and a shortŌĆæterm execution horizon is useful here. You can lock in annual volume commitments for controllers and highŌĆærisk I/O with your ABB partner based on scenario planning, while letting actual callŌĆæoffs for individual modules follow nearŌĆæterm demand signals from maintenance and project work. Stock buffers in your storeroom then absorb the dayŌĆætoŌĆæday variability in failures and small upgrades without forcing you to renegotiate longŌĆæterm supply every time a card fails.

LeadŌĆætime parameters for these buffers should not be static. Demand Driven Technologies recommends periodically measuring actual lead times, cleansing exceptional events, and then reviewing parameters monthly or quarterly. In practice, that means tracking how long it actually takes to receive a replacement AC 800M controller, a particular Select I/O module, or an IEC 61850 gateway, and then adjusting your safety stock assumptions if performance drifts. The goal is not to chase every fluctuation but to keep your planning realistic.

ABBŌĆÖs own services can support this lifecycle view. The Performance Optimization for control systems ŌĆō Harmony service, for example, is structured around a Diagnose, Implement, and Sustain methodology. ABB describes continuous data collection, KPIŌĆædriven analysis, and value modules that expose process and controlŌĆæsystem performance during the Diagnose phase. The Implement phase turns those insights into an agreed improvement plan, and the Sustain phase provides ongoing 24/7 monitoring, trend analysis, and remote expert support under a subscription model.

While that service is framed around performance and modernization rather than pure supply chain, the same monitoring and analysis can highlight chronic hardware stress, unexpected fault patterns, or obsolescence risk on particular modules. Combined with an automation software maintenance or lifecycle management program, this creates a feedback loop: what you learn from operations informs which ABB components you prioritize for spares, upgrades, and longŌĆæterm leadŌĆætime commitments.

Consider a utilityŌĆæscale facility replacing legacy control on critical switchgear and UPS systems with ABB System 800xA. The goal is to migrate to modern controllers, safetyŌĆærated I/O, and integrated power and process automation while maintaining supply continuity.

Early in conceptual design, the team decides on a standard architecture built around a defined set of AC 800M controllers, Select I/O for highŌĆædensity I/O, and S800 I/O where intrinsic safety or legacy wiring dictates. Based on prior projects and current market intelligence, they assign working leadŌĆætime values for each component group, recognizing that controllers and safety I/O are likely to be the longest.

Rather than waiting for the full detailed design to finish, procurement and the ABB partner collaborate to place an early order for the controller families and an initial block of safety and standard I/O, structured under a framework that allows later adjustment of exact module mixes. This mirrors best practices recommended by Vizient for early purchase order release of longŌĆælead equipment and by Ramp for breaking procurement into preŌĆæprocessing, processing, and postŌĆæprocessing stages.

In parallel, the supply chain team builds an integrated schedule covering generators, mediumŌĆævoltage switchgear, UPS systems, and DCS cabinets. Where VizientŌĆÖs data suggests generators may have lead times approaching or exceeding a year, those orders are also advanced, and the DCS delivery dates are synchronized with switchgear delivery to support early functional testing.

Once in operation, the facility applies a demandŌĆædriven approach to spares. Measured lead times for replacement controllers and I/O over the first year feed into a buffer design for the storeroom. The plant allocates higher safety stock to items whose lead times prove long and volatile, while holding leaner levels of more stable, commodityŌĆælike parts. ABB performance optimization services provide ongoing health data on controllers and I/O, so that patterns of stress or obsolescence trigger early planning rather than lastŌĆæminute, expedited orders.

Supply chain practitioners working with demandŌĆædriven models recommend reviewing leadŌĆætime parameters on a regular cadence such as monthly or quarterly. For ABB DCS components, that translates into periodically comparing the lead times you planned for controllers, I/O, and panels with what you actually experienced on orders and replacements. When you see persistent deviations rather than oneŌĆæoff anomalies, adjust your planning parameters and, if necessary, your safety stock. This keeps your project schedules and buffer calculations grounded in reality without creating noise by overreacting to every delay.

Research from Netstock and others shows that thoughtful inventory optimization, including appropriate safety stock on longŌĆælead items, can cut overall holding costs by roughly fifteen to thirty percent while improving service levels. The key is to reserve higher safety stock for items whose failure would be catastrophic and whose replacement lead time is long and volatile, such as critical controllers or safety I/O, while treating less critical, shorterŌĆælead items differently. When you look at the cost of a prolonged outage in a powerŌĆæsensitive facility versus the capital tied up in a small number of extra modules, the economics often favor strategic spares.

Lifecycle programs and performance optimization services from ABB, including offerings that use the Diagnose, Implement, and Sustain structure, focus on keeping existing control systems operating at peak performance. By continuously monitoring system health, analyzing KPIs, and providing expert recommendations, they can expose emerging issues long before they become failures. That gives you more time to plan hardware replacements or upgrades and reduces the need for emergency orders with premium freight. It also helps you make better decisions about when to modernize versus when to continue maintaining a current platform.

In a world where electronic and electrical lead times move faster than most project schedules, treating ABB DCS components as a central part of your power supply resilience strategy is no longer optional. When you design lead time as deliberately as you design oneŌĆæline diagrams, you give your UPS systems, inverters, and protection schemes the control backbone they need to keep the lights on when it matters most.

Leave Your Comment