-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

When an ABB breaker ŌĆ£doesnŌĆÖt work,ŌĆØ the real problem is rarely just the device itself. In critical UPS, inverter, and power protection systems, a misbehaving breaker is usually the visible symptom of deeper issues in loading, wiring, control power, or maintenance practices. As a power system specialist, I have seen seemingly simple breaker complaints escalate into significant downtime for data centers, industrial plants, and commercial facilities because the underlying fault was misunderstood or the breaker was ŌĆ£fixedŌĆØ in the wrong way.

This guide walks through how to interpret ABB breaker problems, how to troubleshoot them methodically, and when repair or replacement makes sense. The focus is on lowŌĆæ and mediumŌĆævoltage circuit protection in industrial and commercial settings, with ABB devices as concrete examples, but the principles are grounded in guidance from ABB documentation, utility experience, and practical troubleshooting texts rather than guesswork.

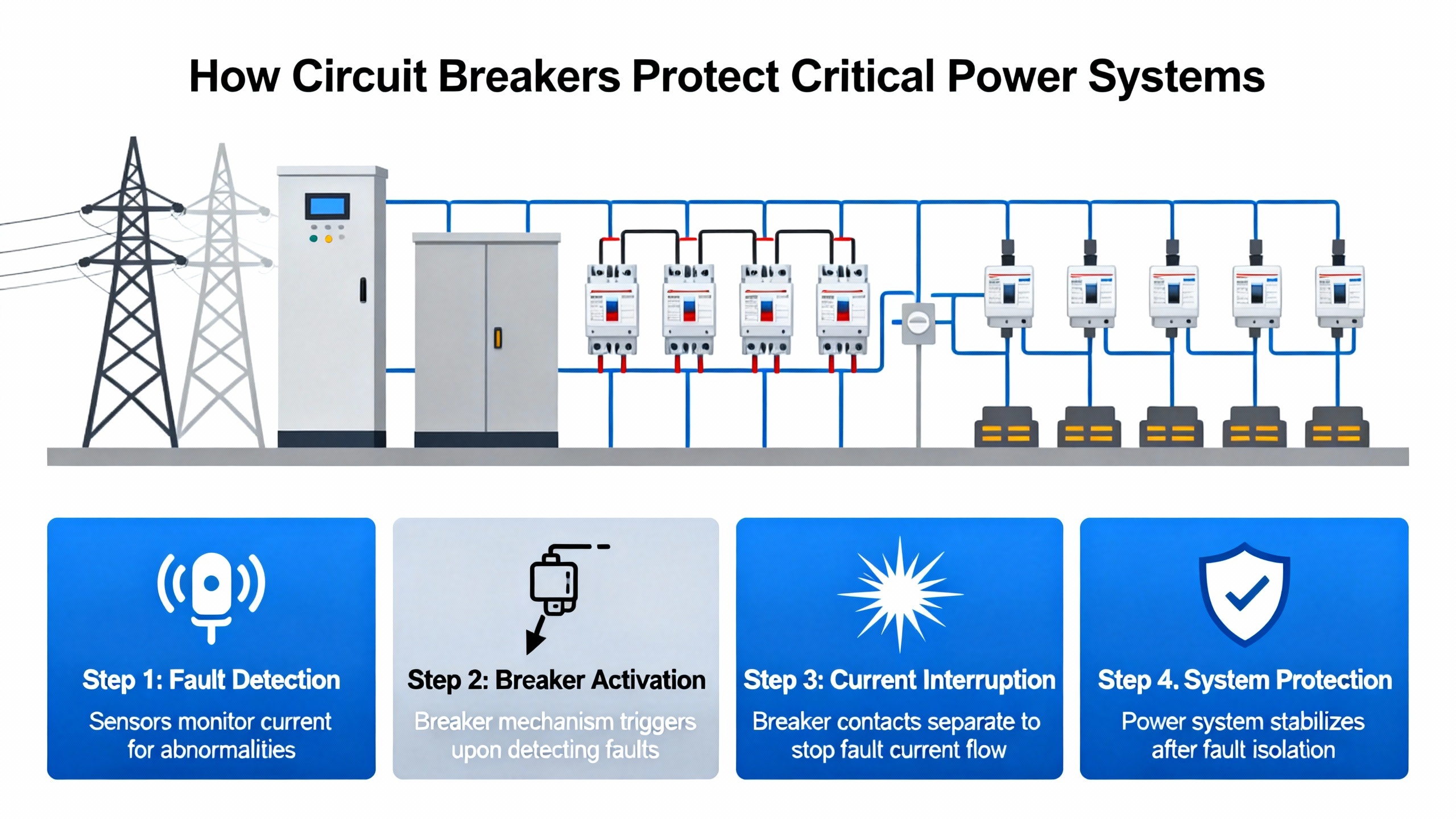

An electrical circuit breaker is a switching device that automatically interrupts current to protect conductors, equipment, and people when faults or overloads occur. Technical guidance from universities and training institutes stresses that tripped breakers are a fundamental safety mechanism to prevent overheating, equipment damage, and fire, not merely an inconvenience that needs to be reset.

ABBŌĆÖs portfolio covers miniature breakers and motor protectors, moldedŌĆæcase devices, electronic miniature breakers (often called eMCBs), and larger lowŌĆævoltage and mediumŌĆævoltage breakers used in switchboards, motor control centers, UPS input and output feeders, and inverter circuits. Several key ideas from ABBŌĆÖs own circuit breaker guide and related material are worth highlighting because they shape how these devices behave when something goes wrong.

The ABB glossary for lowŌĆævoltage selectivity defines ultimate shortŌĆæcircuit breaking capacity (Icu) as the maximum fault current the breaker can safely interrupt, and rated uninterrupted current (Iu) as the continuous current capability that effectively indicates the deviceŌĆÖs physical ŌĆ£size.ŌĆØ Rated shortŌĆætime withstand current (Icw) applies to certain breakers, particularly soŌĆæcalled Category B devices that can carry shortŌĆæcircuit current for a defined time to achieve timeŌĆæbased selectivity, while Category A devices without Icw are used where energyŌĆæbased selectivity is sufficient.

ABB releases also distinguish overload protection (function L), delayed shortŌĆæcircuit protection (function S), instantaneous shortŌĆæcircuit or earthŌĆæfault protection (function I in the sense of an instantaneous element), and directional shortŌĆæcircuit functions (G and D). Thermomagnetic releases come in variants with fixed or adjustable magnetic thresholds, and electronic releases provide even finer adjustment and selfŌĆæprotection, tripping rapidly for very high currents even if instantaneous elements are nominally set to off.

Newer ABB and ABBŌĆæbranded breakers with electronic trip units do more than simply trip. As described in field experience with ABB SACE Tmax XT5H and similar designs, their trip units often act as power quality meters, using voltage taps and bundled sensing wiring attached to each phase to monitor system conditions. ABB also supports advanced diagnostics such as the LEAP tool for Emax and Emax 2 breakers, allowing condition assessment while equipment remains in service.

All of this means that when an ABB breaker ŌĆ£does not work,ŌĆØ you are dealing with a coordinated protection and monitoring device whose behavior is shaped by mechanical mechanisms, electronic sensing, trip curves, and upstream and downstream system design.

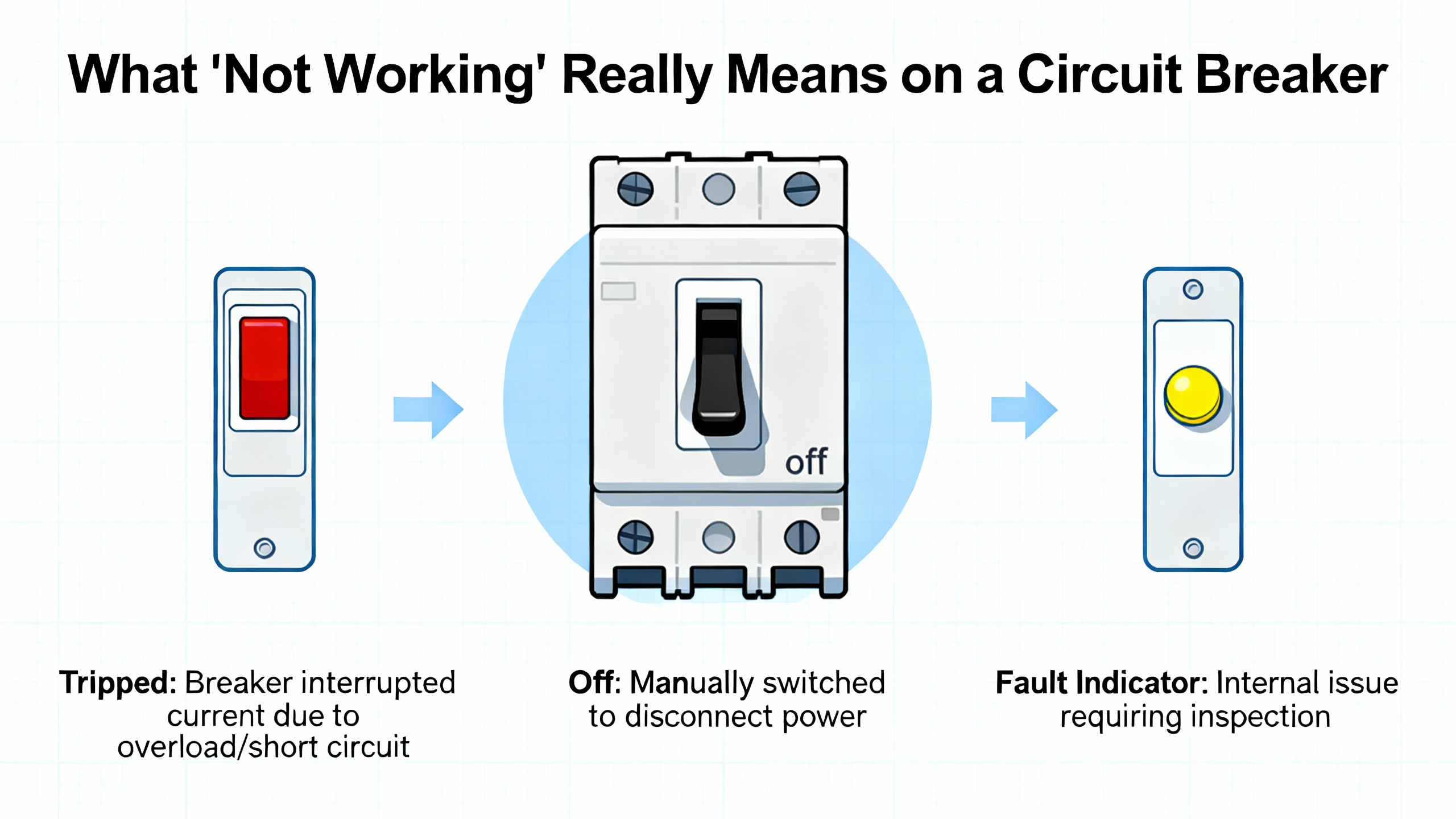

Operators and maintenance teams usually describe breaker problems in plain language: it will not close, it will not open, it trips for no reason, or it seems to operate by itself. A detailed industry analysis of ABB breaker failures groups these symptoms into four operational failure modes, which map surprisingly well to what people see in the field.

| Failure mode | Typical observed behavior | Risk level and impact |

|---|---|---|

| Refusal to close | Breaker command given but contacts do not close; position indicator and lamps disagree | Loss of backup or transfer path, inability to restore power to UPS, inverters, or critical feeders |

| Refusal to trip (open) | Fault indications and high currents, but breaker stays closed | Very high; can burn equipment, trigger upstream trips, and cause bus voltage collapse |

| False trip (ŌĆ£mis-tripŌĆØ) | Breaker opens when there is no fault and no protection operation | Nuisance outages, difficult fault location, potential miscoordination with upstream or downstream devices |

| False closing | Breaker closes although no manual or automatic closing command was issued | Shock to the system, risk of closing into faulted equipment or improperly isolated circuits |

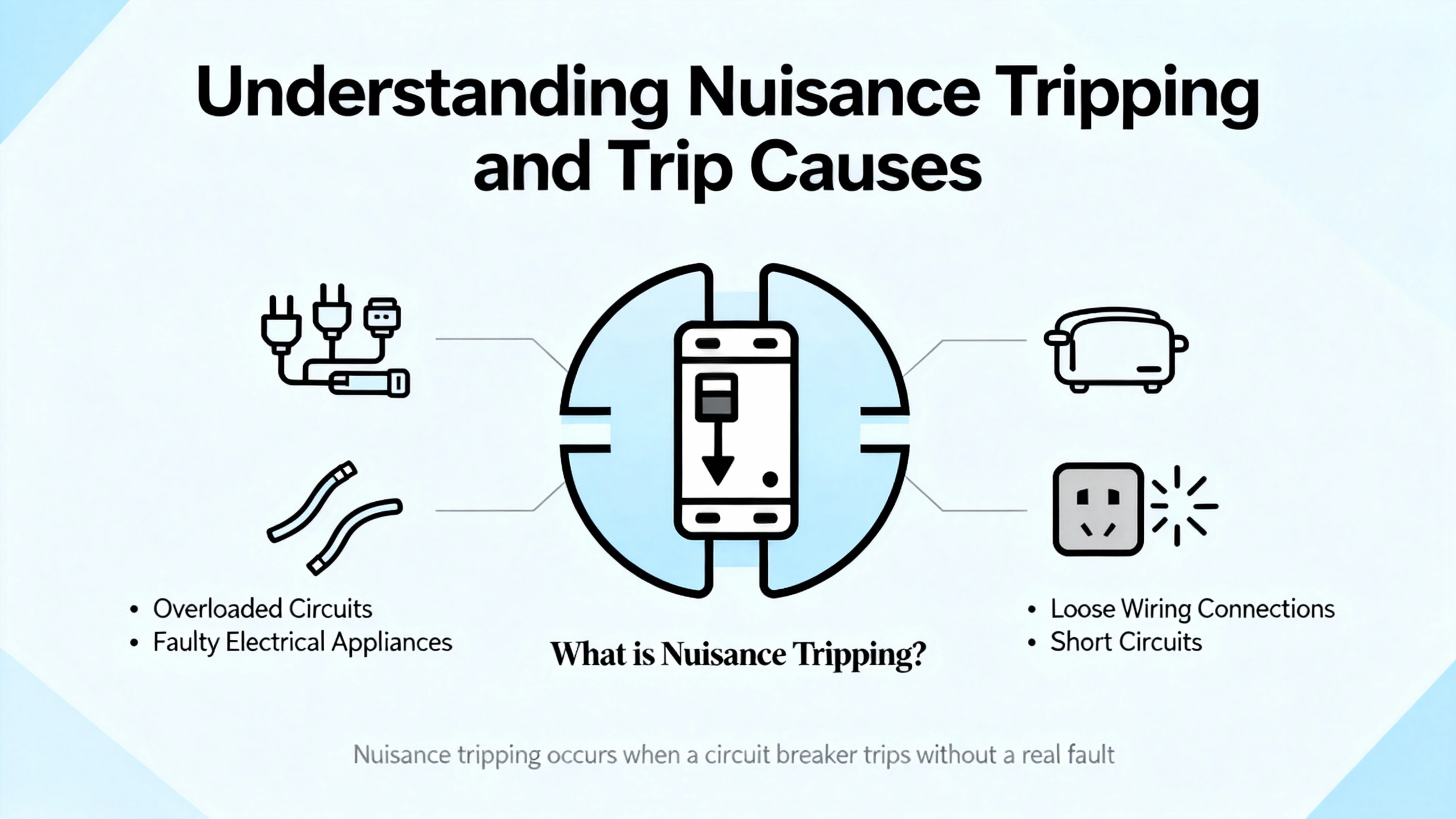

On top of these modes, there are nuisance trips that are genuine protection operations but feel like ŌĆ£misbehaviorŌĆØ to the user. Articles aimed at homeowners and technicians highlight familiar causes: circuit overloads from too many devices on one circuit, short circuits and ground faults from damaged wiring or appliances, and voltage irregularities that stress sensitive equipment. Breakers that repeatedly trip under these conditions are telling you that something in the system, not necessarily the breaker itself, needs attention.

A separate category is mechanical failure of the operating handle or mechanism. In an engineering forum discussing several ABB MS325 motor protection breakers used on a training bench, the manual operating knob failed. The authorŌĆÖs attempts to remove the front knob and access internal components revealed a complex internal mechanism and an enclosed spring area that was difficult to reach even after partial disassembly. That realŌĆæworld case illustrates how ŌĆ£stiff handleŌĆØ or ŌĆ£broken knobŌĆØ complaints may reflect internal mechanical failures that are not straightforward to repair in the field.

All of these behaviors must be interpreted carefully before anyone reaches for tools or replacement parts.

Before diagnosing why an ABB breaker is not working, it is essential to adopt the safety posture recommended by universities, technical institutes, and ABBŌĆÖs own service literature.

Guidance from a major universityŌĆÖs environmental health and safety office on resetting breakers is clear: only trained and authorized personnel should operate or reset building distribution breakers. Before attempting any reset, you should identify and correct the likely cause of the trip instead of repeatedly resetting the breaker. If the breaker trips again immediately after being reset, the recommended action is to leave it in the tripped or off position and call facilities services or a qualified electrician. Bypassing breakers, forcing them to stay on, or removing panel covers without being a qualified electrical worker are explicitly discouraged.

Educational guides from technical institutes on home and small commercial electrical problems add practical cues. Unfamiliar odors, especially a burning smell near electrical panels or equipment, are treated as serious warnings that something is overheating or failing. Excessively hot fixtures, electrical shocks when touching switches or equipment, and abnormally high energy bills are all presented as reasons to involve a licensed electrician rather than attempting doŌĆæitŌĆæyourself fixes.

Industrial troubleshooting guides add another layer: the need for systematic lockout/tagout procedures, verification of the absence of voltage before touching conductors, and appropriate personal protective equipment such as insulated gloves, eye protection, and insulated tools. These texts emphasize that technicians should perform continuity checks with supply disconnected and only then verify operation with live supply, following recognized safety standards throughout.

In critical UPS and inverter systems, these guidelines translate directly into practice. Treat all conductors as energized until proven otherwise; isolate the affected feeder or panel where possible; check for heat, discoloration, or odor around the ABB breaker and its terminations; and resist the urge to ŌĆ£just reset itŌĆØ until you have a plausible explanation for the trip or failure.

One of the most common ABB breaker complaints is nuisance tripping. In the field, this often falls into three observable patterns: overload trips, instantaneous trips when energizing equipment, and rapid reŌĆætrips after reset.

Technical guidance from vocational training programs on common electrical problems defines a circuit overload as too many appliances or devices connected to one circuit, causing the breaker to trip. The practical fix is either to reduce the load on that circuit or have an electrician add or upgrade circuits so the load is shared more appropriately. In commercial settings, this may mean moving UPS or inverter input feeds to dedicated circuits instead of sharing with general receptacle loads.

Another pattern is an immediate trip the moment the ABB breaker is closed. Training material on short circuits explains that when a hot conductor contacts a neutral or ground, a very lowŌĆæresistance path forms, causing a sudden current surge and instant breaker operation. Ground faults, especially in damp locations such as equipment rooms with condensation, behave similarly but involve unwanted current flowing to ground. These conditions are treated as serious fire and shock hazards. Practical advice from safetyŌĆæoriented sources is to inspect for visible damage, scorch marks, or frayed conductors, and to avoid reŌĆæenergizing until the fault is located and corrected.

ABBŌĆÖs own troubleshooting guidance for electronic miniature circuit breakers, summarized in a Rapid TripFix context, adds nuance. A rapidŌĆætrip approach distinguishes between overload, shortŌĆæcircuit, earthŌĆæfault, and nuisance tripping by checking device indicators, reviewing recent changes on the circuit, and measuring load and fault currents with appropriate instruments. One key step is verifying that the breakerŌĆÖs rated current and trip curve are appropriate for the load. For example, breakers with more sensitive instantaneous characteristics may nuisance trip when feeding loads with high inrush currents such as motors, transformers, or certain power electronic loads. If an ABB breaker of a given curve is undersized or misapplied, it may trip rapidly even though there is no fault in the conventional sense.

That same guidance emphasizes load isolation: deŌĆæenergize the circuit, disconnect or switch off all downstream loads, and then reŌĆæenergize the breaker. By reconnecting devices one at a time, you can identify whether a specific UPS, inverter, motor, or branch circuit triggers the trip. This method is particularly useful in scenarios like those discussed on doŌĆæitŌĆæyourself solar power forums, where an ABB breaker dedicated to an inverter repeatedly trips under certain operating conditions.

Finally, nuisance trips can reflect coordination problems rather than defects. ABBŌĆÖs selectivity glossary highlights how instantaneous thresholds and shortŌĆætime withstand ratings interact. If downstream and upstream breakers are not coordinated, a fault may cause an upstream ABB device to trip unexpectedly, even though a downstream breaker could have cleared the fault more selectively. In complex commercial and industrial systems, timeŌĆæcurrent curves must be chosen and set to avoid such misoperations.

A breaker that refuses to close under command is more than a nuisance; in critical power systems it can prevent backup supplies, standby generators, or redundant UPS modules from taking over during an event. A detailed ABBŌĆæfocused analysis of refusalŌĆætoŌĆæclose failures divides the problem into operator error, control circuit issues, and mechanical faults.

The simplest check is to rule out misoperation. In some cases, a control switch may be released too quickly or not fully engaged, and a second deliberate attempt using the correct procedure resolves the issue. Once that is eliminated, attention turns to the closing control circuit. Industry guidance suggests verifying the presence of control power, checking fuses in the closing circuit, examining the closing contactor and coil, and inspecting auxiliary contacts that either permit or block a closing command. If a closing circuit fuse is blown, the contactor is inoperative, the closing coil is faulty, or auxiliary contacts do not change state correctly, the breaker may never receive a proper closing signal.

ABB troubleshooting material links certain indication patterns to these issues. For example, if both red and green indicator lamps are dark, that suggests loss of control power or an open control loop. If a green lamp flashes without any change in mechanical position, the breaker may not have closed mechanically despite an electrical attempt. If the red lamp comes on briefly and then goes off with a trip alarm, the breaker may be closing into a fault or failing to latch mechanically and then tripping open.

Mechanical causes include loose or dropped connecting rods in the mechanism, a stuck closing iron core, a mechanism that fails to reset fully to its preŌĆæclosing position, nonŌĆæreturn of opening linkages, and stuck shafts or pins that cause a ŌĆ£hollowŌĆØ closing motion where the handle moves but the contacts do not fully engage. There is also a subtle case where operating voltage for the closing electromagnet is too high, causing failure to latch, or too low, preventing sufficient magnetic force. Some guidance uses the rule of thumb that control voltage should not fall below roughly eighty percent of its nominal value for reliable operation.

In ABB MSŌĆæseries devices and other compact breakers, mechanical complexity can make these faults difficult to correct. The MS325 disassembly case shows that simply reaching the internal spring suspected of failure required removing the front cover after considerable effort. The rear of the device mainly exposed power contacts and springs, not the front mechanism. That experience underscores the importance of deciding when field adjustments are genuinely achievable and when the device should be removed and either replaced or returned to an authorized service facility.

Refusal to open on command or during a fault is the most dangerous failure mode an ABB breaker can exhibit. The same industrial analysis that classifies refusalŌĆætoŌĆæclose failures describes refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip as highly hazardous because it prevents fault clearance. If a breaker feeds a transformer or essential bus and fails to open during a fault, currents can rise to destructive levels, burning equipment and forcing upstream breakers to operate in a stepŌĆæbyŌĆæstep fashion until a higherŌĆælevel device clears the fault. The result can be loss of voltage on entire buses or sections of the plant.

Operators can recognize refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip from a combination of symptoms: large swings in current or voltage on meters, falling bus voltage, illuminated fault panels, and protection records showing that relays have operated without any corresponding change in the breakerŌĆÖs mechanical position. In that situation, guidance from the ABB failure analysis is to manually open the breaker immediately if it is safe to do so. If transformer currents and sounds are abnormal, the recommendation is to open the upstream power breaker first to protect the transformer, then work backward to locate the nonŌĆæresponsive breaker.

Once the immediate danger is contained, a structured diagnostic sequence is needed. Electrical aspects include verifying trip supply voltage, which again should not drop below about eighty percent of rated value, and checking the integrity of the trip circuit, including fuses, wiring, relay contacts, and the trip coil. A blown fuse in the trip supply, a broken control wire, poor contact in relay circuits, or a burned trip coil can all result in a breaker that never receives sufficient energy to open.

Mechanical refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip, by contrast, involves stuck or underŌĆæimpact trip cores, dried or contaminated lubrication in linkages, or broken mechanical parts that prevent the stored energy mechanism from releasing fully. Practical troubleshooting texts on motors and control circuits stress the importance of verifying both electrical and mechanical operation in tandem, using timing and travel analysis where possible. The Electrical Power Research InstituteŌĆÖs work on ABB KŌĆæLine breakers for nuclear plants illustrates an advanced approach: timing and travel analysis, reduced controlŌĆævoltage testing, and trending of asŌĆæfound and asŌĆæleft data are used to ensure that breakers open correctly under a range of conditions.

Because of the risk involved, refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip cases are prime candidates for manufacturer or specialist involvement rather than purely inŌĆæhouse repair, especially in highŌĆæconsequence environments such as data centers, petrochemical plants, and generating stations.

Not every ŌĆ£breaker problemŌĆØ originates inside the ABB device. The same ABBŌĆæfocused failure analysis that describes refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip also defines false trip and false closing behaviors, and other field reports highlight the role of external conditions like wiring and condensation.

False trips, sometimes called misoperations or ŌĆ£misallocationŌĆØ in translated material, occur when a breaker trips automatically even though relay protection has not operated and there is no system shortŌĆæcircuit or obvious abnormal condition. Causes cited include personnel misoperation or inadvertent activation due to vibration, incorrect or overly sensitive protection settings, faults in current transformer or voltage transformer secondary circuits, poor secondary insulation, and DC control systems with double grounding that unintentionally energize trip circuits.

False closing, where a breaker closes with no apparent closing command, is equally troubling. Diagnostics rely on confirming that no manual command was given and observing that the red position indicator remains on or flashes even when the handle is in a nonŌĆæclosing position. Suspected causes include DC supply double grounding, faulty automatic reclosing relays whose contacts stick, and closing coils with unusually low resistance that respond to transient DC pulses. The recommended response is to open the misŌĆæclosing breaker, remove closing fuses if reclosing recurs, and then investigate both control circuitry and mechanical latching.

External flashover events show yet another mechanism. In a case involving a miniature ABB breaker, engineers observed a flashover between incoming phase terminals. A detailed discussion concluded that the breaker was likely the victim of an external fault rather than the root cause. Possible contributors included stray strands of flexible wiring bridging terminals, condensation droplets forming a conductive path in a humid cabinet, and metal offcuts or debris left inside that shifted during operation. One contributor even noted the possibility of deliberate sabotage using conductive compounds. The practical takeaway was to examine cabinet design for places where condensation can drip onto terminals, to carefully terminate extraŌĆæflexible conductors to avoid stray strands, and to perform insulation resistance testing from the main disconnect through to the small breakers before reŌĆæenergizing.

These examples are reminders that ABB breakers sit within wider electrical environments. Apparent device failures may be symptoms of wiring practices, environmental control, and controlŌĆæsystem design as much as manufacturing issues.

Once obvious external and system issues are addressed, testing is needed to assess breaker health and verify repairs. Here, modern ABB devices demand more care than older, purely mechanical designs.

Field experience with ABB SACE Tmax XT5H breakers highlights the complexity introduced by electronic trip units and their associated wiring. These units often have bundles of multicolored control and sensing wires attached to each phase conductor. When technicians perform insulation resistance testing using megohmmeters, these auxiliary circuits can affect readings and may themselves be stressed by the test voltage if not isolated. In one emergency call involving wet breakers, technicians disconnected the multiŌĆæpin connectors associated with the trip unit wiring before testing. Even then, measured insulation resistance of around twelve megohms between phases and from phase to ground in the presence of moisture led them to perform detailed inspection and cautious testing before returning the equipment to service. The recommended practice is to identify and isolate tripŌĆæunit wiring before highŌĆævoltage insulation tests on modern ABB breakers.

MediumŌĆævoltage vacuum breakers introduce additional considerations. A technical article on 10 kV vacuum breakers explains that the vacuum interrupterŌĆÖs internal pressure must remain within a defined vacuum range to maintain dielectric strength. Vacuum bottle leakage, insulation failure, and mechanism misoperation can all cause serious downtime. Recommended prevention includes visual inspection of glass envelopes, where a dull shielding cover or dark red arc glow indicates degraded vacuum, and periodic powerŌĆæfrequency withstand tests at fortyŌĆætwo kilovolts every three years. Handling vacuum leakage may involve adjusting contact overtravel to keep wear within about 0.12 in, measuring opening distance and overtravel, replacing defective vacuum interrupters or entire breakers, and reŌĆætesting travel, timing, and contact bounce. While this guidance is not limited to a single manufacturer, a German case study involving ABB VM1 10 kV breakers showed that vacuum bottle leakage due to moisture and pollution could be significantly reduced. After adopting a strict threeŌĆæyear test cycle and improving sealing materials, the failure rate dropped by about thirtyŌĆæfive percent within two years, demonstrating the value of disciplined testing and improved environmental sealing.

For lowŌĆævoltage ABB breakers, ABBŌĆÖs own service organization promotes condition assessment methods such as thermographic analysis to detect abnormal temperature patterns, functional testing of control and measurement functions either on site or in workshops, and riskŌĆæbased asset assessment tools that help prioritize which breakers need attention. Combining risk analysis, inŌĆæservice diagnostic tools, functional testing, and thermographic surveys provides a comprehensive view of breaker health without waiting for failures to occur.

Across all voltage levels, practical troubleshooting handbooks emphasize using the right tools in the right order: continuity and insulation checks with the supply safely disconnected; verification of proper control voltages; timing and travel measurements where equipment and safety rules permit; and finally, carefully controlled live tests to confirm correct trip behavior. When testing ABB breakers with advanced electronic trip units, the key is to avoid subjecting sensitive electronics to inappropriate test voltages or currents by following manufacturer recommendations or, when those are not available, by isolating auxiliary circuits as in the field examples described.

Deciding whether to repair or replace an ABB breaker is both a technical and a strategic reliability question. Experience from nuclear plants, industrial facilities, and ABBŌĆÖs own service practice shows that different classes of breakers warrant very different approaches.

For large lowŌĆævoltage breakers such as ABB KŌĆæLine units used in nuclear plants, overhaul and refurbishment make sense. A major guidance document from the Electrical Power Research Institute published on February 16, 2001, assembled an industryŌĆæwide consensus on overhaul maintenance tasks for these ABB breakers. It did not serve as a stepŌĆæbyŌĆæstep procedure, but rather as a reference that explains the purpose and justification for each overhaul task, including lubrication, reduced controlŌĆævoltage testing, timing and travel analysis, trending, asŌĆæfound testing, troubleshooting, and receipt inspection. Utilities use this kind of material to develop siteŌĆæspecific maintenance programs, defend their procedures to regulators, and standardize practices across fleets. In that context, structured repair and overhaul of ABB breakers by trained technicians following documented tasks is a rational strategy.

For modern lowŌĆævoltage ABB breakers with sophisticated electronic trip units, ABBŌĆÖs own service offerings, including LEAP diagnostics for certain breaker families and thermographic surveys, are designed to extend equipment life and improve reliability through proactive monitoring. In many cases, field ŌĆ£repairŌĆØ consists of targeted component replacement, careful adjustments, and updated settings carried out by ABB technicians or partners, supported by diagnostic data.

At the other end of the spectrum, small ABB devices such as MS325 motor protection breakers or miniature eMCBs are physically compact and mechanically complex. The MS325 case shows that accessing a suspected broken spring required significant disassembly from the front, and even then the spring chamber was not easily reachable. The back of the device exposed mainly power connections and springs, offering little access to the front mechanism where the fault lay. The post did not end in a simple replacement of a part but in the realization that comparing the faulty unit to a working one would be necessary just to identify which component was damaged. That experience, combined with the absence of definitive manufacturer repair instructions in the discussion, illustrates why many practitioners treat such devices as nonŌĆæserviceable and choose replacement instead of internal mechanical repair once faults are confirmed.

False trips, false closings, and external flashovers present another consideration. Where investigations like the miniature ABB breaker flashover case point to external causes such as stray wire strands, condensation, or debris, the ŌĆ£repairŌĆØ may focus more on wiring practices and cabinet design than on the breaker, perhaps accompanied by replacement of the affected device as a precaution. Similarly, where ABB failure analyses identify refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip conditions, the combination of high risk and complex mechanical and control interactions often makes manufacturer repair or replacement the only acceptable option.

The common thread across these scenarios is that ABB breakers should be treated as part of a larger reliability and maintenance program rather than as isolated components. Practical troubleshooting texts and ABB service literature converge on a few shared themes: use systematic methods instead of trial and error, develop maintenance tasks with clear justification, take advantage of condition monitoring where available, and design programs that fit the criticality of each breakerŌĆÖs role in the system.

When ABB breakers protect UPS, inverters, and other power electronics in industrial and commercial systems, a disciplined approach to ŌĆ£not workingŌĆØ complaints prevents small issues from turning into major outages.

In overload and nuisanceŌĆætrip scenarios, particularly when new UPS modules, servers, or process loads have been added, the first step is to review loading and breaker selection. Training material on preventing breaker trips stresses that highŌĆæpower appliances should not share circuits with many other devices and that persistent trips can be a sign that additional dedicated circuits or upgrades are required. Applied to ABB breakers, that means verifying that rated current and trip curves match the evolved load, not just the original design.

When immediate trips occur at energization, experience from Rapid TripFixŌĆæstyle guidance and home electrical safety resources aligns around a few questions. Did something change immediately upstream or downstream, such as recent wiring work or a new inverter? Are there signs of short circuits or ground faults such as scorch marks or visible damage? Does the breaker behave differently when loads are disconnected and reintroduced one by one? In UPS and inverter contexts, this may involve testing whether the inverter itself, rather than the feeder wiring, is the source of fault currents that drive the ABB breaker open.

RefusalŌĆætoŌĆæclose and refusalŌĆætoŌĆætrip cases demand closer attention to control circuits and mechanisms. The ABB failure analysis suggests checking control power, fuses, closing contactors and coils, and auxiliary contacts, and then moving on to mechanical linkages and stored energy mechanisms if electrical checks are satisfactory. Verifying control voltage within acceptable limits is critical in both directions: too low and coils will not operate reliably; too high and latching problems may appear. In UPS and inverter switchboards, where DC control systems are common, double grounding in DC circuits can have unexpected effects on trip and closing behavior, including false trips and false closing.

In mediumŌĆævoltage ABB breaker applications feeding large UPS or distribution transformers, the vacuum breaker guidance and ABB VM1 case study provide a roadmap for reducing failures. Regular powerŌĆæfrequency withstand tests at appropriate test voltages, careful tracking of contact wear and overtravel, proactive replacement of vacuum interrupters showing signs of degradation, improved environmental sealing, and attention to insulation cleanliness all contribute to lower failure rates. The reported thirtyŌĆæfive percent reduction in leakageŌĆærelated failures over two years in the ABB VM1 example illustrates the payoff of such programs.

Across all these contexts, ABBŌĆÖs maintenance services and the broader troubleshooting literature converge on the importance of thermographic inspections, condition monitoring, riskŌĆæbased asset assessment, and systematic testing methods. Rather than waiting for an ABB breaker to refuse to close during a transfer or refuse to trip during a fault, building a program that identifies weak points early is the most effective way to keep UPS, inverter, and power protection systems reliable.

For building and industrial distribution systems, guidance from safety organizations and electrician training programs is that significant electrical issues should be handled by qualified, licensed professionals. Small ABB breakers, especially compact motor protectors like the MS325, have mechanically complex internal mechanisms that are not straightforward to service, as field disassembly attempts show. Larger ABB breakers can be overhauled, but that work is typically done by trained technicians following detailed maintenance tasks rather than improvised in the field.

Training and troubleshooting material on breaker trips and ABB electronic breakers indicates that high inrush currents, mismatched trip curves, and overloads are common reasons for rapid tripping when new loads are added. A systematic approach is to deŌĆæenergize, connect the ABB breaker with all downstream loads off, then reintroduce the UPS or inverter and other loads one by one to see which triggers the trip. If the breakerŌĆÖs rating or curve is not appropriate for the deviceŌĆÖs inrush and steadyŌĆæstate current, or if wiring defects or ground faults are present, tripping may occur even when the breaker itself is healthy.

Situations where an ABB breaker refuses to trip, shows signs of internal damage, or is part of a mediumŌĆævoltage or nuclearŌĆærelated system warrant specialist involvement. Industry guidance on ABB KŌĆæLine and VMŌĆæseries breakers, along with ABBŌĆÖs own maintenance and diagnostic services, shows that timing and travel analysis, reduced controlŌĆævoltage testing, thermographic surveys, and structured overhaul tasks are most effective when performed by teams with specific training and tools. Even in less critical environments, repeated unexplained trips, false closings, or refusalŌĆætoŌĆæclose behavior should prompt consultation with ABB or a qualified service provider rather than continued adŌĆæhoc resets or internal mechanical tinkering.

ABB breakers sit at the heart of many critical power systems, from UPS and inverter switchboards to mediumŌĆævoltage feeders. Treating them as part of a larger protection and maintenance strategy, using the structured troubleshooting and testing approaches described here, turns ŌĆ£breaker not workingŌĆØ from a vague complaint into a solvable reliability problem.

Leave Your Comment