-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Industrial and commercial power protection has changed dramatically over the last decade. A modern electrical room that combines Schneider automation, UPS systems, inverters, static transfer switches, and power monitoring no longer behaves like a simple radial feeder. It behaves like a tightly coupled, dataŌĆædriven system.

Research summarized in a recent review hosted by PubMed Central explains that as industrial processes become more automated and data intensive, diagnosing faults gets harder, not easier. Multiple control loops, complex communication paths, and advanced algorithms mean that a single disturbance can produce symptoms in several places at once. In practice, that means a nuisance trip, a UPS transfer, and a string of SCADA alarms might all be different manifestations of one underlying integration problem.

Work from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on fault detection and diagnostics tools in building automation shows the same pattern. As more functionality moves into software and networked controls, the critical path for reliability shifts toward data quality, analytics, and automated decision logic. The hardware is still important, but the difference between ŌĆ£stable powerŌĆØ and ŌĆ£recurring unexplained outagesŌĆØ is often the integrity of the automation and its integration, not the copper and steel.

For power protection engineers working with Schneider automation, that shift has two consequences. First, fault diagnosis cannot stop at ŌĆ£the UPS trippedŌĆØ or ŌĆ£the breaker failed.ŌĆØ It has to explore how automation, communications, and analytics interacted with the power equipment. Second, system integration verification becomes as important as equipment factory acceptance tests. You are no longer just buying devices; you are commissioning a coordinated cyberŌĆæphysical system.

Fault management is often used loosely, so it helps to be precise about the terminology before tying it back to SchneiderŌĆæcentric power systems.

Classic fault diagnosis literature summarized by Greg Stanley and Associates defines a fault very broadly. A fault is any departure from desired operation, not only outright hardware failure. In a power protection context, that could be anything from an inverter that runs within nameplate but at poor efficiency, to a UPS that transfers late, to a misconfigured protection setting that leaves a feeder underŌĆæprotected. The underlying rootŌĆæcause fault is the fundamental issue that actually requires correction: for example, an incorrect CT ratio, a firmware defect, or a control logic error.

What operators see in the control room are symptoms. A symptom is any observed variable or event used to detect or isolate a fault. In Schneider automation environments this might be a breaker status mismatch between a device and SCADA, an unexpected DCŌĆæbus voltage trend on an inverter, or a recurring transfer to bypass on the same UPS during certain load changes. When that observation is the result of an explicit check or test, it becomes a test result rather than a passive symptom.

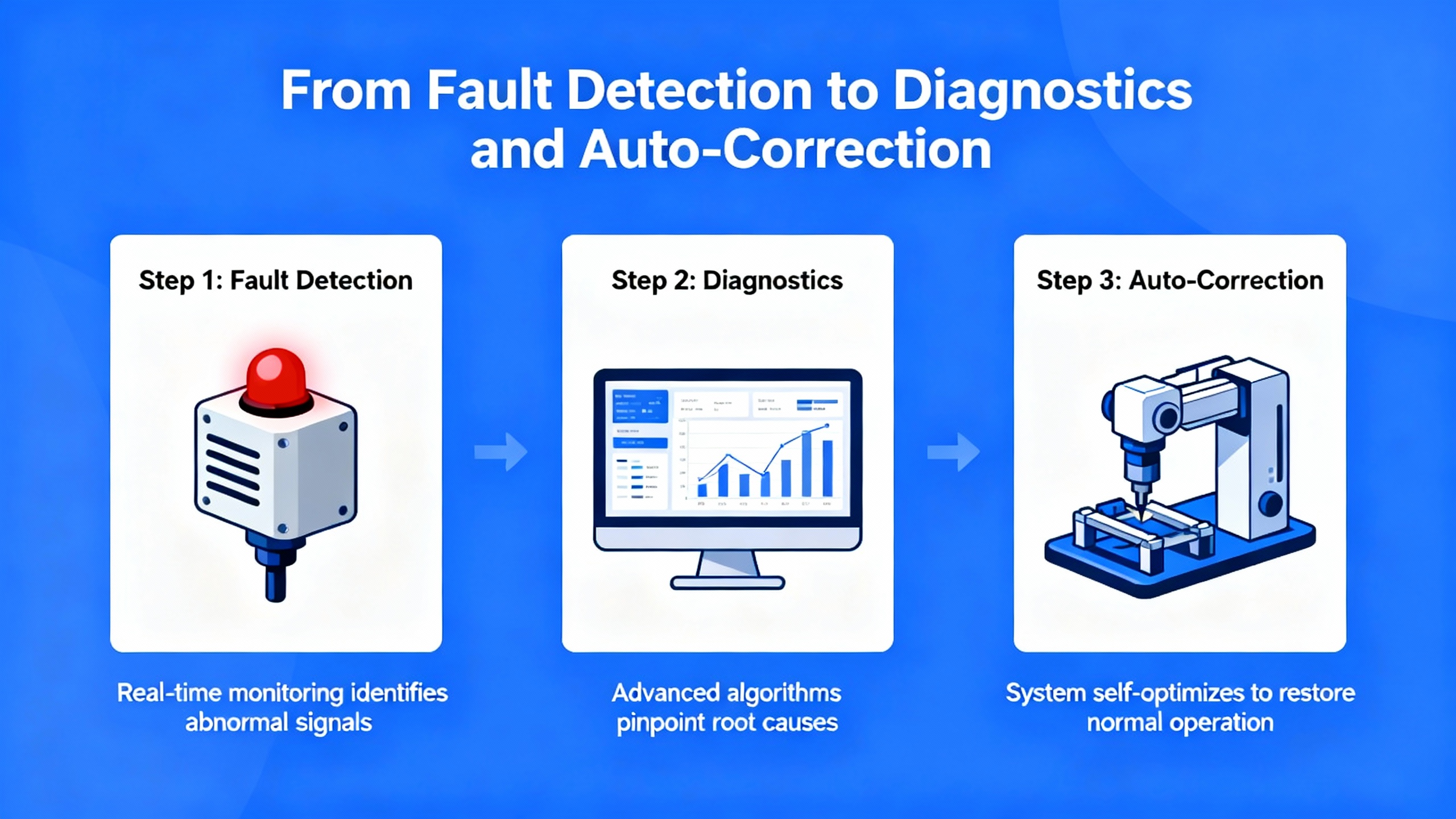

Fault detection is simply recognizing that something is wrong. Fault diagnosis, or isolation, is the process of pinning down which root cause is actually responsible so that the right corrective action can be executed. In real power systems, multiple concurrent faults are common. A noisy CT, a delayed communications path, and a misŌĆætuned control loop can all be present at once. The research notes emphasize that largeŌĆæscale systems rarely satisfy the ŌĆ£single fault at a timeŌĆØ assumption, and practical diagnostic strategies must cope with overlapping issues.

Most SchneiderŌĆæbased power networks still rely heavily on traditional alarms. A paper from ClimaCheck, which focuses on HVAC and refrigeration, draws a useful distinction that applies directly to power:

Alarms are reactive signals. They trigger when a simple threshold is crossed for a variable such as current, temperature, or pressure. By the time a UPS overŌĆætemperature alarm fires, for example, the problem is already severe enough that you are in damageŌĆæcontrol mode.

Early warnings are predictive indicators based on deviations in system performance and trend analysis. In power terms, this might be a slowly rising harmonic distortion level, a subtle change in inverter efficiency at partial load, or an increase in transfer count on a particular static switch compared to its peers. These are the kinds of patterns that automated fault detection and diagnostics (FDD) is designed to catch.

Multiple sources, including ClimaCheck and smartŌĆæbuilding FDD buyer guides, point out that hidden performance faults can drive energy waste on the order of ten to thirty percent in HVAC systems. The same principle holds for power protection: a UPS that runs hot due to a control or cooling fault will waste energy and wear out assets long before a conventional alarm fires.

Xempla and other smartŌĆæbuilding FDD providers describe FDD as a continuous analytics layer that sits on top of existing control systems, ingesting sensor data, comparing it to models or historical baselines, detecting anomalies, and then diagnosing likely causes. Nexus Labs describes this stack in four logical layers: integration, data processing, analytics, and visualization, with the FDD engine transforming raw signals into ranked, actionable issues rather than streams of unfiltered alarms.

Most commercial FDD products today stop at diagnosis. According to a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory field study of automated fault correction in large building HVAC systems, common tools identify faults and notify operators, but they still rely on human intervention for the fix. The researchers extended these platforms with autoŌĆæcorrection algorithms that could directly adjust building automation system parameters when certain types of faults were detected, under carefully controlled conditions.

The study is notable for two reasons. First, it proved that automated routines can correct faults in real facilities without degrading performance or comfort, as long as the algorithms are rigorously tested. Second, it showed that closing the loop between detection and correction significantly increased achievable energy and operational savings and reduced reliance on continuous human oversight.

For Schneider automation in power systems, that suggests an evolution path. Start with robust detection and diagnosis that leverages existing controllers, meters, and SCADA. Then, in very wellŌĆæbounded cases, introduce supervised autoŌĆæcorrection, for example adjusting noncritical setpoints or resetting certain control logic when a recognized, lowŌĆærisk pattern appears. The automation should never be allowed to ŌĆ£run awayŌĆØ with changes, but carefully scoped autoŌĆæcorrection can dramatically reduce nuisance work while keeping the human in control.

With those concepts in place, the next question is how to verify that a SchneiderŌĆæcentric automation and protection architecture will actually support effective fault diagnosis. This is where system integration best practices from the broader software world become directly relevant to power engineers.

An integration guide from Osher, which looks at enterprise systems, argues for an APIŌĆæfirst, eventŌĆædriven approach. The idea is to define clear contracts for how subsystems communicate and to design around asynchronous events rather than tightly coupled pointŌĆætoŌĆæpoint links. In practice, when you apply that mindset to a power system, you get cleaner separations between field devices, Schneider controllers, power monitoring software, FDD analytics, and enterprise platforms such as CMMS or energy management systems.

SmartŌĆæbuilding FDD stacks described by Nexus Labs mirror this structure. There is an integration layer that connects to field systems; a data layer that cleans, normalizes, and models the data; an analytics layer that runs FDD algorithms; and a visualization layer where operators work. When you view a Schneider automation architecture through this lens, you can verify integration at each layer instead of treating the system as a black box.

The relationships between layers are easier to discuss with a simple conceptual map.

| Layer | Example components in a SchneiderŌĆæcentric power system | Primary verification focus |

|---|---|---|

| Field and power devices | UPS modules, inverters, static transfer switches, switchgear, sensors, protection relays | Correct wiring and scaling, timeŌĆæstamped measurements, consistent status indications |

| Control and automation | Schneider programmable controllers, remote I/O, local HMI panels | Deterministic logic execution, correct mapping of I/O points, failŌĆæsafe behavior |

| Supervision and monitoring | SCADA, power quality meters, power monitoring software | Accurate aggregation, consistent oneŌĆæline representation, reliable event logging |

| Analytics and FDD | Performance monitoring, conditionŌĆæbased maintenance tools, AFDD platforms | Data quality checks, model accuracy, meaningful earlyŌĆæwarning indicators |

| Enterprise and cloud | CMMS, reporting, energy portals, remote dashboards | Secure integration, correct data synchronization, reliable context for decisionŌĆæmaking |

System integration verification means proving that each layer does its job and that the contracts between layers are honored. For example, when a UPS module reports an overload, the controller should act correctly, the SCADA should show accurate status and events, the FDD engine should see the same data stream and classify the event correctly, and the CMMS should receive and log the work order in a way maintenance teams can trust.

Several of the research notes focus on integration failures in other industries that have direct analogs in power systems. APPSeCONNECT highlights how data synchronization failures, broken APIs, and middleware issues in business systems can cost millions through abandoned carts, mismatched inventory, and failed transactions. CTI Electric points out that as industrial plants connect more PLCs, IoT devices, and cloud systems, the cyberattack surface grows and integration paths often become the weakest link.

In a Schneider automation environment, similar integration faults can easily masquerade as equipment problems. A misaligned time base between a protection relay and the SCADA historian may make it look as if a breaker tripped after a UPS transfer rather than before. A mislabeled Modbus register can cause an FDD engine to ŌĆ£seeŌĆØ a DCŌĆæbus voltage excursion that does not actually exist. A firewall rule change can interrupt a critical status signal, leading the automation layer to assume a device has failed and issue unnecessary transfers or alarms.

From a fault diagnosis perspective, if you skip systematic integration verification, you risk chasing the wrong root cause. You swap boards, recalibrate sensors, and even replace UPS modules when the real issue is a missing data mapping, a timestamp offset, or a network bottleneck.

Robust SchneiderŌĆæbased fault diagnosis is not about choosing a single magical algorithm. The processŌĆæcontrol literature represented in the research notes emphasizes that real systems use hybrid approaches, tuned carefully for robustness against noise, sensor faults, and model errors.

Greg StanleyŌĆÖs overview of industrial diagnostic methods distinguishes modelŌĆæbased reasoning, causal models, pattern recognition, neural networks, and ruleŌĆæbased systems. The PubMed Central review on intelligent fault detection goes further, describing parityŌĆæspace techniques, fuzzy logic, neural networks, robust transition structures, and residualŌĆæbased frameworks. In practice, these methods are often layered.

In a Schneider automation project, modelŌĆæbased methods can capture the physics of a UPS or inverter under normal conditions. DataŌĆædriven methods, such as statistical pattern recognition or machine learning, can then operate on the residuals between model expectations and actual measurements to identify patterns associated with different faults. RuleŌĆæbased logic, informed by protection design and operating procedures, can enforce guardrails so that diagnostics remain interpretable and safe.

LargeŌĆæscale FDD deployments described in the notes show that hybrid approaches deliver better scalability. For example, transition structure methods group fault models so that detection can be done in stages, with more detailed models executed only when needed. That keeps computational load manageable even in systems with many possible fault modes.

All the FDD and faultŌĆæfinding sources stress the tradeŌĆæoff between sensitivity and false positives. Set alarm thresholds too tight and you get early warnings but drown the operations team in nuisance alarms. Set them too loose and you miss developing problems or catch them only when the cost is high.

Greg Stanley treats this as a generalization of tuning alarm thresholds, with robustness tuning as a firstŌĆæclass design task. The PubMed Central review describes defining permissible error thresholds between process outputs and model outputs based on historical and heuristic knowledge of the process. If the error stays within the threshold, the system is considered faultŌĆæfree; if it exceeds the threshold, a fault is suspected.

ClimaCheckŌĆÖs experience with AFDD in HVAC shows that when earlyŌĆæwarning logic is configured thoughtfully, the number of urgent alarms and associated downtime events can drop significantly. The same principle can be applied to SchneiderŌĆæbased power systems. Use performance analytics to identify deviations early, but tune alerts so they highlight issues that matter: patterns that correlate with real failures or efficiency loss, not every tiny fluctuation around a setpoint.

Several notes warn that automated fault detection systems depend heavily on sensor data and that sensor failures themselves rank among the most common faults. The PubMed Central paper describes simulated faults in transmitters and valves using stepŌĆætype disturbances in transmitter span and zero calibration. The detection logic must distinguish between sensor faults and process faults, otherwise you end up trying to ŌĆ£fixŌĆØ equipment that is actually working while the real issue is a bad measurement.

Translating that into power protection, current transformers, voltage transducers, temperature sensors, and communication links should all be treated as diagnosable assets. Your Schneider automation strategy should include checks for sensor drift, bias, or dead zones, not only checks for UPS and inverter faults. If a DCŌĆæbus voltage channel is stuck at a plausible value, that should be flagged as a potential measurement fault, not silently trusted.

Robust architectures also avoid trusting a single sensor or model absolutely. Greg Stanley notes that practical systems approximate and combine evidence via weighting rather than relying on any one input. In power systems, that may mean crossŌĆæchecking measured power against the product of measured voltage and current, or comparing status indications from independent sources before taking critical actions.

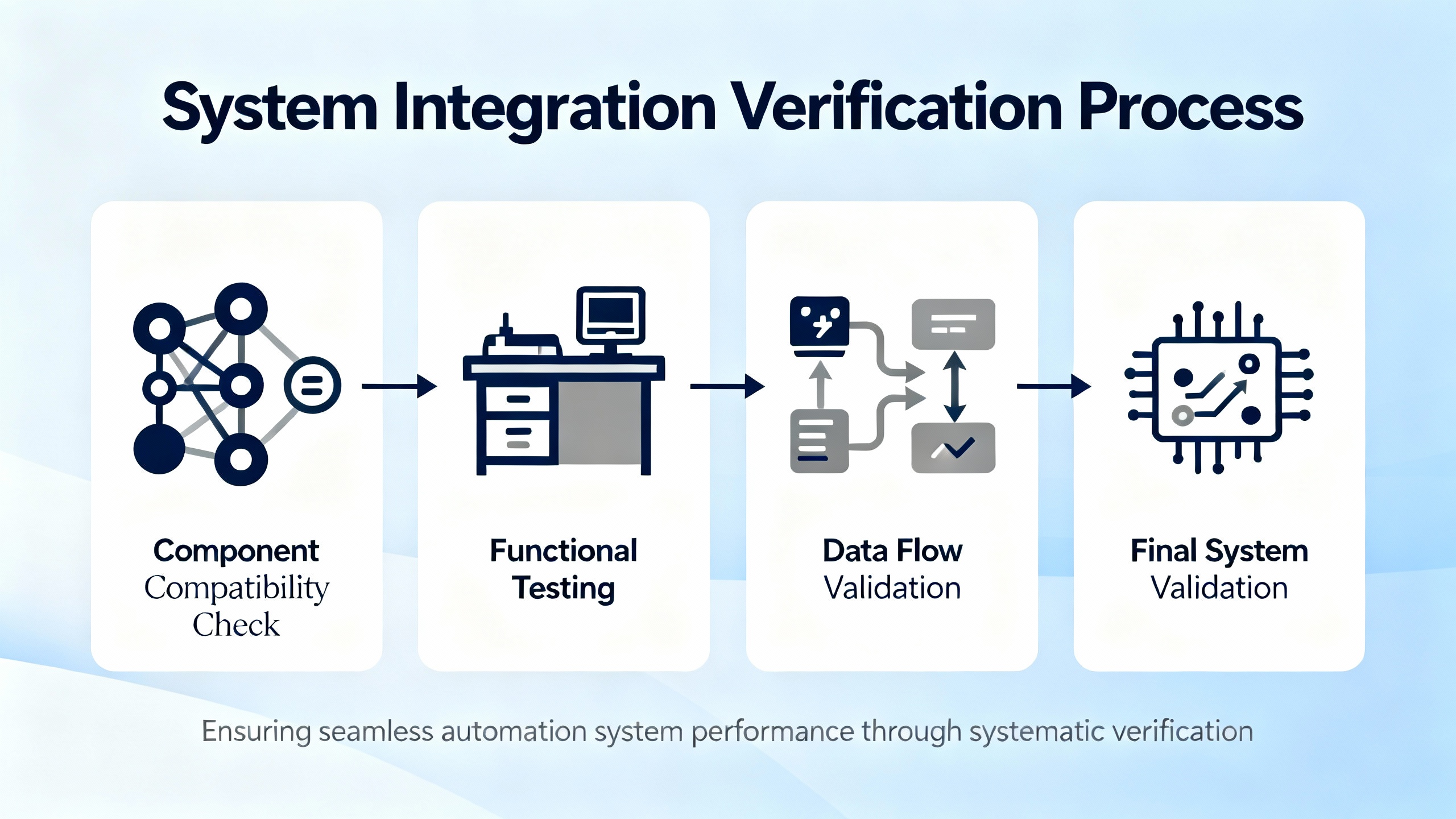

System integration testing practices from enterprise software and packaged application testing translate surprisingly well to Schneider automation projects, especially when the goal is reliable fault diagnosis and protection.

Testing guides from Testingmind, Functionize, and Opkey describe system integration testing as the phase where interactions between subsystems are verified endŌĆætoŌĆæend. Rather than focusing on individual modules in isolation, these practices validate that data, control, and error handling flow correctly across the entire landscape.

Integration testing can be approached incrementally or in a ŌĆ£big bangŌĆØ fashion. The research notes suggest that incremental approaches, where subsystems are integrated and tested step by step, enable earlier bug detection and easier isolation of faults. BigŌĆæbang approaches, where everything is wired together at once, can work for smaller, simpler systems but are harder to debug when issues arise.

Applied to Schneider automation with UPS and inverters, an incremental strategy might start by validating communication and logic between controllers and a single UPS. Once that path is stable, SCADA integration is added, followed by power monitoring and FDD analytics, and finally enterpriseŌĆælevel connections such as CMMS and reporting. At each stage, test cases are designed not only for normal operation but also for fault conditions: simulated overloads, communication loss, status mismatches, and time synchronization errors.

Modern testing platforms described in the notes emphasize automation, selfŌĆæhealing tests, and rich logging. Even if you are not using those specific tools in an electrical project, the principles carry over. Automate repeatable tests where possible, especially regression checks after configuration changes. Ensure that logs contain enough detail and correlation identifiers to reconstruct complex fault sequences. Treat integration tests as living assets that evolve with the system.

The PubMed Central review discusses ŌĆ£seeded faultŌĆØ testing and accelerated testing as ways to validate diagnostic methods. Seeded fault testing introduces controlled defects into a system so that algorithms can be calibrated and evaluated. This concept is highly relevant for SchneiderŌĆæbased power systems during commissioning and major upgrades.

In practice, that might involve temporarily misŌĆæconfiguring a noncritical setpoint within a safe range, injecting a known offset into a measurement channel, or simulating the behavior of a stuck breaker status bit using test equipment. The FDD engine and automation should then detect and classify these induced anomalies correctly. If they do not, you discover limitations in your fault models and integration paths before real faults occur.

TransitionŌĆæstructure methods and residualŌĆæbased techniques described in the research allow the diagnostic engine to decide which model bank to consult based on error patterns. During integration verification, you can step through those decision paths explicitly. For example, verify that an overcurrent signature routes diagnostics toward protection or load faults rather than toward UPS control anomalies, while a harmonic distortion signature routes toward nonlinear loads or inverter switching behavior.

Modern integration errorŌĆæhandling guidance from APPSeCONNECT stresses the importance of monitoring, automated retries, and predictive analytics in keeping dataflows healthy. CTI Electric warns that as more industrial facilities adopt IoT devices and cloudŌĆæbased control, their cyberattack surface grows, and legacy PLC and SCADA components without strong security become attractive entry points.

For Schneider automation controlling power protection, system integration verification must therefore extend beyond pure functionality. It should also validate how the system behaves under partial failures and securityŌĆærelevant scenarios. Examples include interrupted communications between a UPS and controller, expired or changed credentials for remote access, and delayed or dropped events on a congested network segment.

Error handling strategies outlined in the integration notes are directly relevant: automated retries for transient communication failures, graceful degradation when a downstream service is unavailable, and predictive analytics that identify unusual patterns in data or traffic before they become outages. Because a cyber incident can present itself as a process anomaly, your FDD design should incorporate context from security monitoring where possible, so that it can distinguish between equipment degradation and suspicious, coordinated changes.

The research notes on industrial automation troubleshooting highlight cybersecurity as a major operational risk. Ransomware that encrypts control logic, weak passwords on remote access points, and malware introduced through removable media can all disrupt operations, cause downtime, and even damage equipment.

The risk is amplified when modern Schneider automation is integrated with older legacy devices that have minimal builtŌĆæin security. CTI ElectricŌĆÖs guidance points out that older PLC and SCADA components often lack security features, and when they coexist with modern networked systems, they can become back doors into the wider control network.

For fault diagnosis and system integration verification, that means two things. First, some ŌĆ£faultsŌĆØ in your UPS or inverter behavior might actually be consequences of hostile actions or unauthorized changes. An unexpected schedule change, a modified protection setting, or a repeated spurious trip could be symptoms of compromised credentials or malware, not random failures. Second, integration verification should include checks that security controls are enforced consistently across old and new components.

Recommended strategies from the notes include stronger password policies, hardened remote access through VPNs and multiŌĆæfactor authentication, strict control of USB use and software updates, and network segmentation with compensating controls around legacy assets. Predictive analytics for error prevention, as described in the integration errorŌĆæhandling research, can also help. Machine learning models that watch for unusual traffic patterns or error bursts around critical Schneider controllers can provide early warnings of emerging cyber issues.

From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs perspective, it is important to treat cybersecurity as part of power system fault management, not as a separate, purely IT concern. A compromise that disables or confuses automation can have the same visible effect as a multiŌĆædevice failure, but the mitigation path is very different.

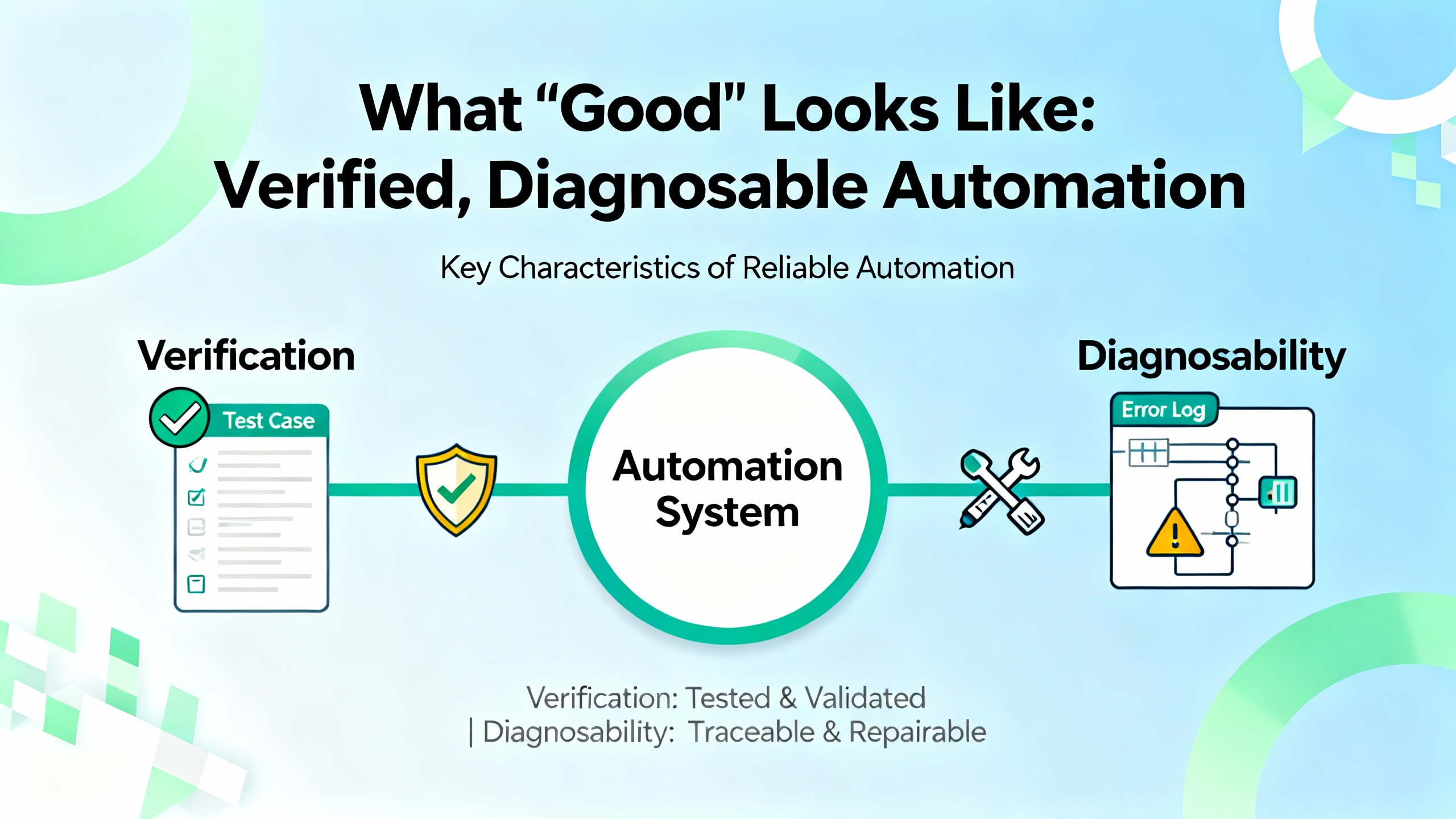

Pulling together the research insights and practical experience, it becomes possible to sketch what a wellŌĆæverified, diagnostically capable Schneider automation and power protection system looks like.

At the basic level, you see simple threshold alarms tied directly to device measurements and statuses. Diagnostic work is manual and reactive. Fault finding relies on the skill of individual technicians, following structured procedures such as MCP Technical TrainingŌĆÖs sixŌĆæstep method: gathering evidence, analyzing it, locating the fault, determining and removing the cause, rectifying the fault, and then checking the system. This is necessary but not sufficient in a highly integrated environment.

At the intermediate level, you add an FDD layer. Guided by the smartŌĆæbuilding FDD literature from Nexus Labs and Xempla, this layer ingests data from Schneider controllers and power devices, normalizes it, applies ruleŌĆæbased and modelŌĆæbased algorithms, and presents operators with a prioritized list of issues. The focus shifts from raw alarms to actionable diagnostics. Maintenance becomes more proactive, and operational teams start to see patterns and recurring problems across sites.

At the advanced level, you incorporate predictive analytics and, selectively, autoŌĆæcorrection. Following the examples from Lawrence Berkeley National LaboratoryŌĆÖs autoŌĆæcorrection field study and ClimaCheckŌĆÖs AFDD experience, algorithms not only detect and diagnose but also propose or implement bounded corrective actions. These might include resetting certain control states, adjusting noncritical limits, or scheduling conditionŌĆæbased maintenance. The system uses robust statistical methods, such as those described in the PubMed Central review, to evaluate confidence in diagnoses and avoid dramatic actions when the evidence is ambiguous.

Across all these levels, strong system integration verification remains foundational. It ensures that diagnostic and control logic actually see the same reality the power devices experience. It validates that error handling, security controls, and data synchronization behave as designed, reducing the chance that a fault in the integration fabric will confuse or mislead the diagnostics.

Most of the documented field deployments of automated FDD and autoŌĆæcorrection described in the research notes are in HVAC and building systems. However, the underlying ideas are technologyŌĆæagnostic. Wherever you have sensors, automation, and complex interactions, continuous analytics can add value. In SchneiderŌĆæbased power systems, the same pattern applies: FDD can track performance, catch hidden inefficiencies, and detect emerging faults earlier than simple alarms, as long as it is tuned to the characteristics of power equipment.

The research summarized from PubMed Central and Industry 4.0 fault detection work shows that both modelŌĆæbased and dataŌĆædriven methods are useful. Deep learning and advanced AI can be powerful, especially with rich historical data, but they are not the only way to gain reliability. Many successful systems combine straightforward physical models, residual analysis, and ruleŌĆæbased logic with moderate dataŌĆædriven components. For Schneider automation projects, it is often better to start with wellŌĆædesigned hybrid diagnostics and highŌĆæquality data than to jump straight to complex AI.

The safest way to begin is to treat fault diagnosis and system integration verification as a single program rather than separate efforts. Start by clarifying what ŌĆ£faultsŌĆØ actually matter for your critical power goals. Then ensure that your Schneider controllers, UPS and inverter measurements, SCADA, and any emerging FDD tools share a consistent data model and time base. From there, you can introduce structured diagnostic logic, validate it through incremental integration testing and seeded faults, and only then consider more advanced analytics or autoŌĆæcorrection.

Reliable power protection today depends as much on the quality of your Schneider automation and system integration as on the robustness of your UPS and switchgear. When fault diagnosis is grounded in hybrid FDD methods, supported by verified integration, and informed by cybersecurity realities, it becomes a strategic capability rather than a firefighting chore. The facilities that make that shift do not just ride through disturbances more gracefully; they run leaner, learn faster from every fault, and build a power infrastructure that is ready for the next wave of automation.

Leave Your Comment