-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

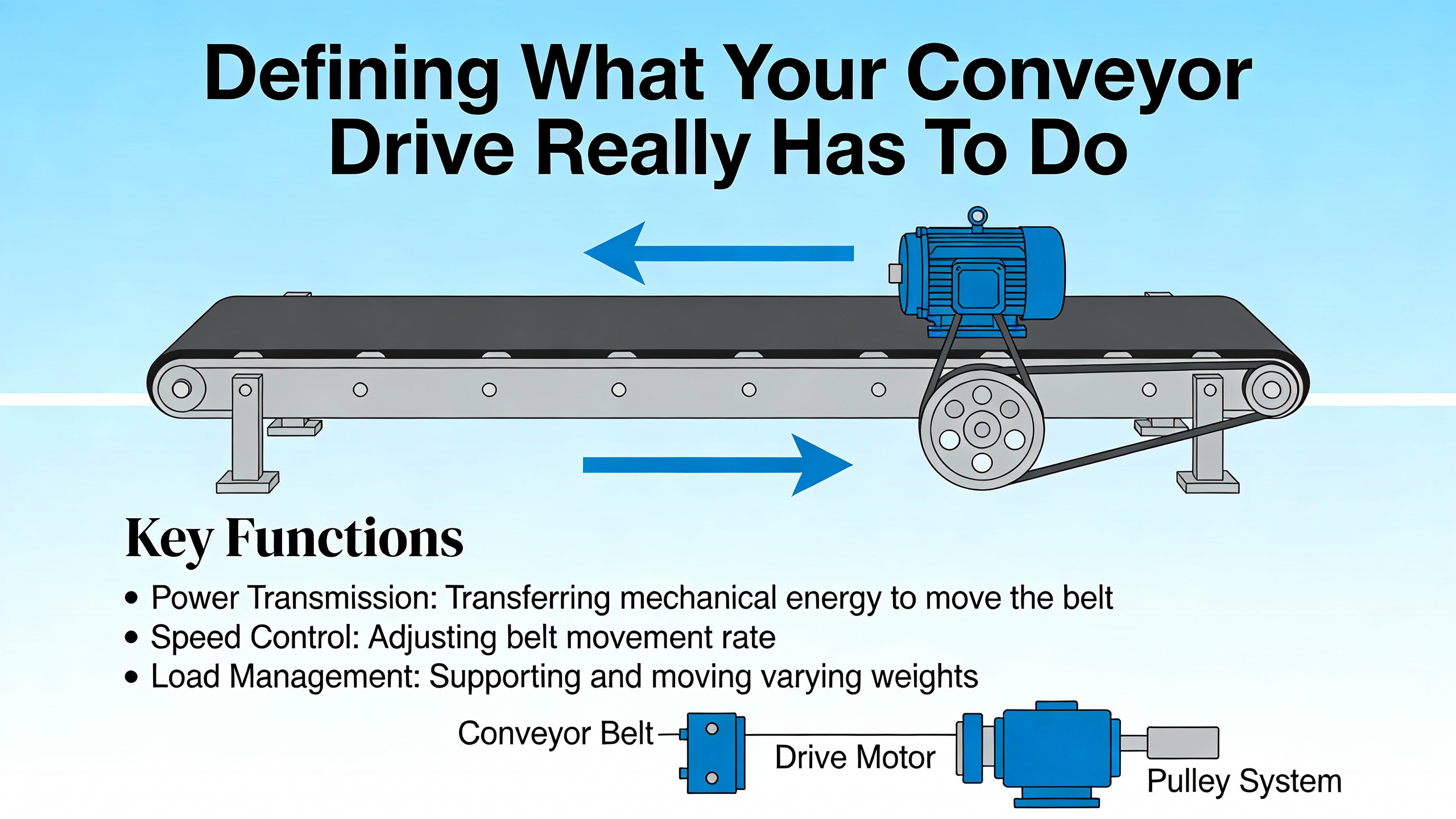

Conveyor lines are often the spine of a plant. They touch almost every product, connect critical processes, and quietly set the ceiling on how much throughput your automation can truly deliver. When a conveyor stops, everything upstream and downstream feels it. Industry case studies from sources such as Impomag and Lafayette Engineering put the cost of unplanned conveyor downtime in the thousands of dollars per hour, and in highŌĆævolume distribution as much as about fourteen thousand dollars per minute. From a power and reliability standpoint, the drive system is where electrical energy becomes mechanical work. That drive system is also where power quality issues, design mistakes, and weak maintenance practices show up first.

Writing as a power system specialist focused on UPS, inverters, and power protection, I see the same pattern repeatedly. Plants invest heavily in warehouse management systems, scanners, and PLCs, but treat the conveyor drive as a commodity. The result is overŌĆæ or underŌĆæsized motors, fixedŌĆæspeed drives where variable speed is clearly needed, and no clear strategy for protecting drives and controls from power disturbances. The good news is that the conveyor and power literature is remarkably consistent on what works. Experts from Binkelman, Coal Age, AEC Carolina, EZG Manufacturing, MLT Group, Lafayette Engineering, and others converge on a set of practical design and maintenance principles that reliably improve uptime, safety, and energy performance.

This article organizes those principles around three decision questions every operations or engineering leader should answer before committing to a conveyor drive strategy: what do you really need the drive system to accomplish, how will you make that drive reliable across its life, and how will you integrate it into your power infrastructure so that a voltage event does not become a production crisis.

A drive system that is perfectly reliable but sized for the wrong job will still underperform. The conveyor designers highlighted by AEC Carolina, Binkelman, Macawber India, and Lafayette Engineering all start from the same place: product characteristics and required throughput.

Product characteristics are more than a catalog description. They include size, weight, shape, surface, material, and any special traits such as abrasiveness, fragility, moisture content, or explosiveness. AEC Carolina stresses that these characteristics determine the conveyor type, belt surface, and speed needed for stable transport. Macawber India goes even further, noting that issues such as flammability, corrosiveness, or the need to maintain specific product temperature all influence conveyor choice. These product traits in turn drive the torque, starting capability, and speed range that the drive system must deliver.

Material type directly influences belt and cover selection, which feeds back into required power. Binkelman points out that rubber belts are preferred for abrasive materials, while PVC belts are better suited for lighter, nonŌĆæabrasive loads. When temperatures are high, compounds such as EPDM or abuseŌĆæresistant Grade 1 materials can handle the environment but often come with different friction and tensioning characteristics. For the drive system, that means different slip margins on the drive pulley and different starting torque to overcome belt inertia and load.

Throughput is the second major driver. AEC Carolina defines throughput as the volume of material moved in a given time, typically units per minute or per hour, and notes that throughput requirements directly inform conveyor speed, drive selection, and overall system sizing. Binkelman reinforces the point that belt speed should be based on both the type and volume of material. Higher speeds can cause spillage or damage to fragile items, while speeds that are too low create bottlenecks and push workŌĆæinŌĆæprocess into the aisles. As an example, a line moving three hundred and fifty cases per minute, similar to the figures cited by Impomag, will move about twentyŌĆæone thousand cases in an hour. If a design error forces operators to slow that line by just ten percent to avoid spillage, the plant gives up more than two thousand cases per hour of potential capacity without ever changing the shift schedule.

Space and layout constraints amplify these choices. AEC Carolina and Macawber India both emphasize that available floor and ceiling space shape feasible conveyor types and geometries. Spiral conveyors, overhead sections, tubular drag systems, and inclines are often used to make the most of vertical space when floor space is limited, but each geometry changes the load profile that the drive must overcome. Steeper inclines generally require more torque or specialized belts such as cleated or highŌĆæfriction designs described by Material Flow and IBT, which again loops back to drive sizing.

The operational environment is equally important. Macawber India and YFConveyor both highlight the impact of dust, high temperature, and cleanliness requirements on conveyor and material choices. In food or pharmaceutical lines, EZG Manufacturing and Nercon describe the use of stainless steel frames and hygienic belt materials, which may impose limits on allowable motor and gearbox locations or cooling arrangements. In heavyŌĆæduty mining or precast applications, EZG Manufacturing notes that frame integrity, shaft strength, and toughness are the dominant factors. Drive systems in those environments must tolerate higher shock loads, more frequent stops and starts under load, and long duty cycles.

When you define these parameters up front, the drive system becomes a calculated outcome instead of a guess. Bulk density, moisture content, particle size, and flowability determine the load seen by the belt and the power needed, as outlined in Coal AgeŌĆÖs discussion of conveyor sizing. From there, belt width, speed, and drive horsepower or kilowatt rating follow logically. Overdesign and underdesign both carry costs. Coal Age warns that undersized components lead to breakdowns and bottlenecks, while oversizing drives raises capital cost and can reduce efficiency under light load.

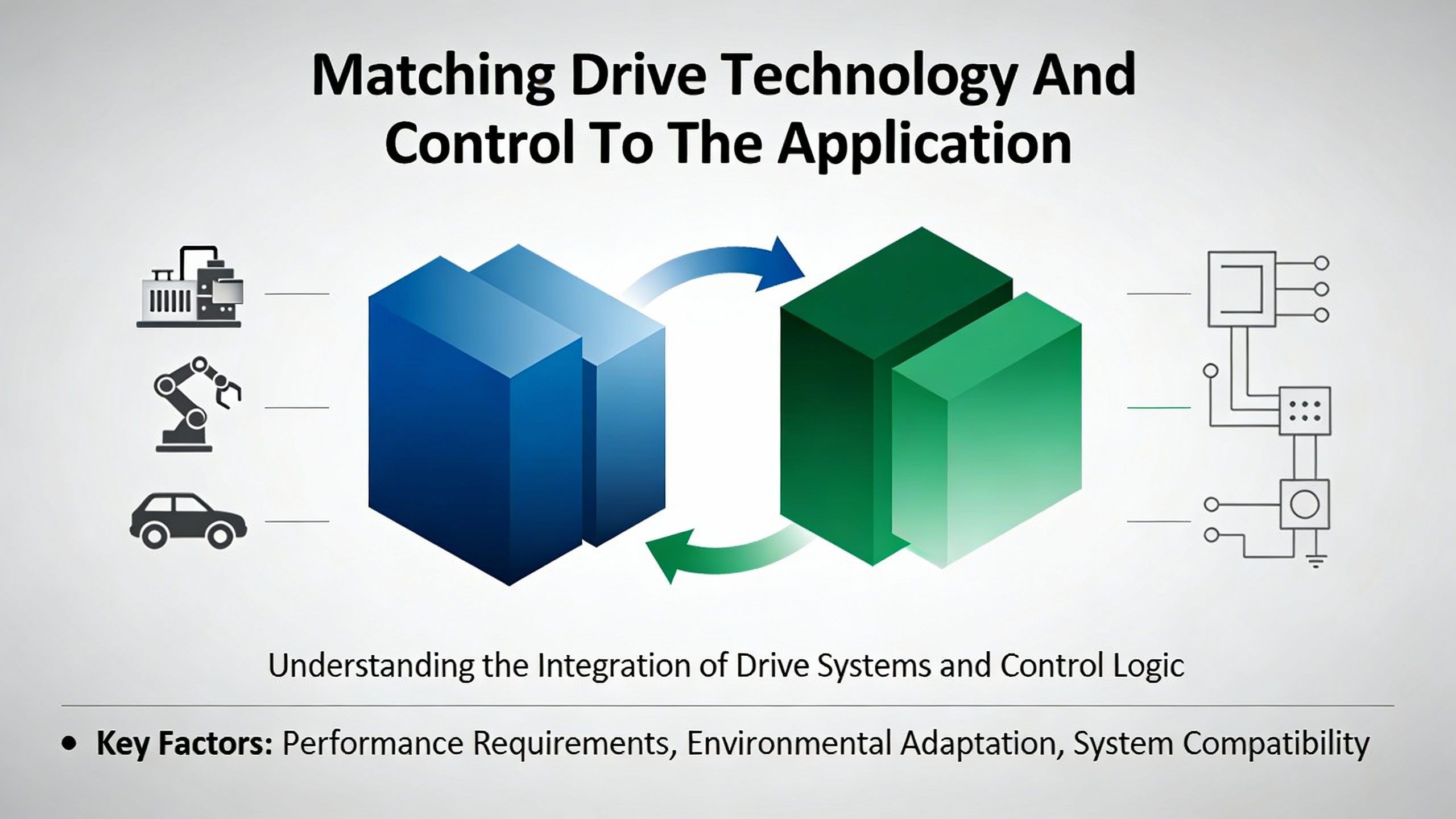

Once the mechanical and material requirements are clear, the next decision is how the conveyor should be driven and controlled. Across the sources, three themes emerge: using properly sized drives with adequate starting torque, favoring variable speed where flow varies, and integrating drives tightly with control and sensing.

Coal Age emphasizes that drive systems must be designed to handle both typical operations and fully loaded starts. Heavy loads dramatically increase starting torque requirements, and failure to account for this drives belt slippage, nuisance trip events, and shortened component life. Variable frequency drives are called out as an increasingly common solution because they provide soft starts, reduce inrush current, and give finer speed control. That combination lowers shock loading on belts and structure, reduces current peaks seen by the power system, and enables better line balancing with upstream and downstream equipment.

Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs design guidance is consistent with this view. Component selection, including motors and drives, has to match load capacity and speed requirements while also meeting energy efficiency targets. They note that energyŌĆæefficient motors and variable speed drives are key levers for improving operating efficiency without sacrificing performance. YFConveyor adds that the choice between centralized drives and distributed drives affects energy use, load sharing, and control complexity, and that pairing appropriate drive configurations with modern controls and sensors enables smoother operation.

Speed control becomes especially important in automated sortation and accumulation. CiscoŌĆæEagle and IBT both describe how advanced control logic, sensors, and realŌĆætime monitoring adjust conveyor speed and zone control to prevent jams and maximize density. CiscoŌĆæEagleŌĆÖs discussion of dynamic zone allocation shows how zone length can be adjusted to carton size, increasing product density and throughput. IBT notes that automation can monitor belt tracking, material load, and speed in real time, reducing human error and potentially cutting energy consumption through better control.

Drive technology choices also carry maintenance and reliability implications. Pit & Quarry reports that conventional conveyor drives often require frequent lubrication and attention, and that switching to lowŌĆæmaintenance technologies such as drum motors can stretch service intervals to about fifty thousand operating hours. For plants with limited maintenance staff, that reduction in lubeŌĆærelated failures and service tasks can be a compelling reason to favor integrated motorŌĆædrum solutions when the application allows.

From a power systems viewpoint, variable speed drives and modern servo or vector drives change the nature of the electrical load. They introduce nonŌĆælinear currents and can be sensitive to power disturbances. At the same time, they offer tremendous control benefits. The right response is not to avoid these drives, but to plan for their power quality needs and to coordinate drive settings with power protection devices so that nuisance trips do not become an everyday reality.

To make these choices concrete, consider a warehouse conveyor that normally runs at half of its maximum speed because downstream packing cannot keep up. A fixedŌĆæspeed drive forces operators to cycle the conveyor on and off or rely on mechanical accumulation. A properly sized variable speed drive, synchronized with sensors and the warehouse management system as described by IBT and CiscoŌĆæEagle, can slow or stop zones intelligently, reducing energy use and mechanical wear. Over a year of twoŌĆæshift operation, that can mean thousands of hours of reduced running time on motors and belts without a single missed order.

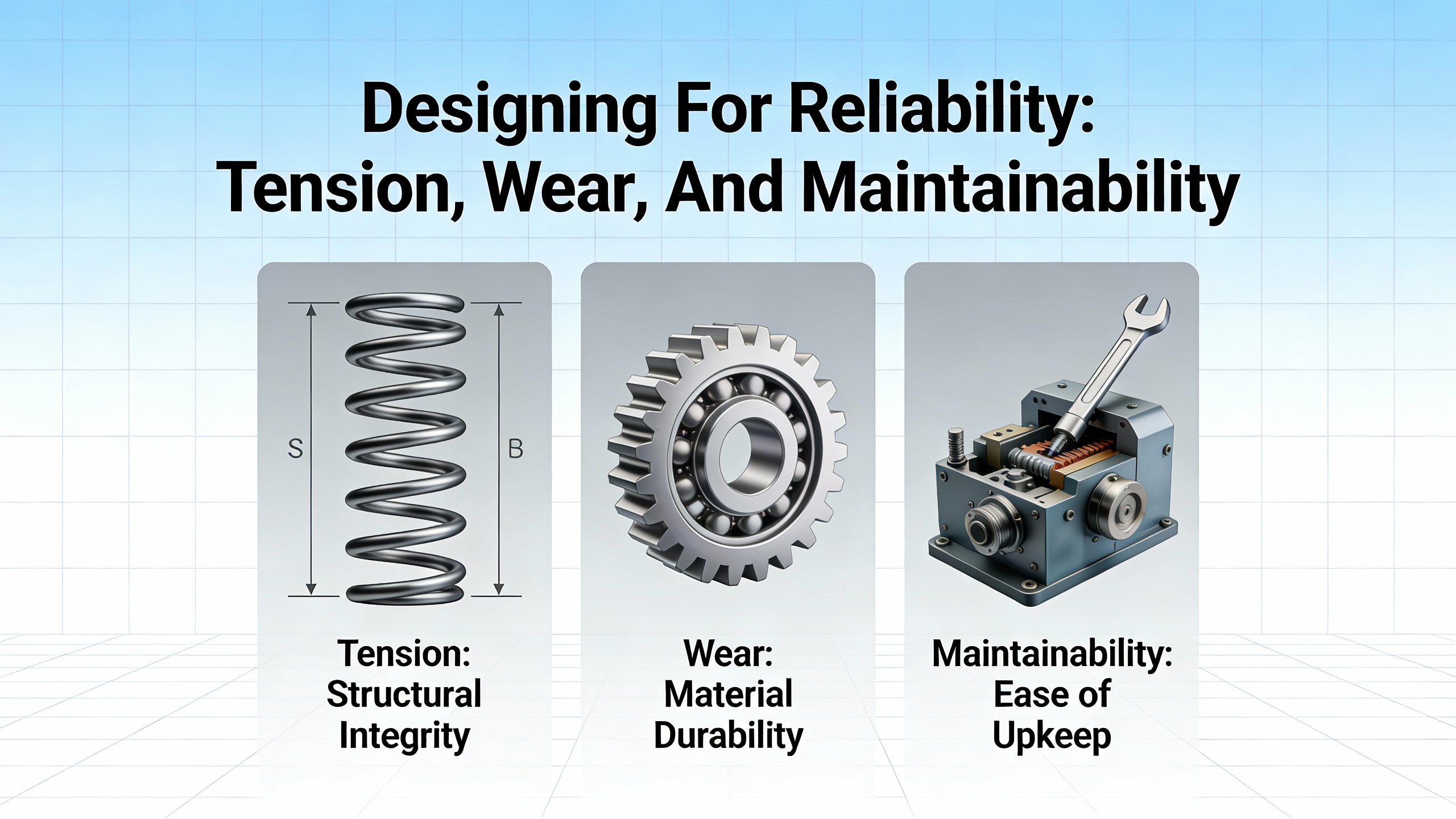

Even the bestŌĆæspecified drive will underperform if the mechanical system around it is neglected. The maintenance guidance from EZG Manufacturing, MLT Group, Conveyors247, Element Logic, Lafayette Engineering, and others is remarkably aligned: focus on belt tension and tracking, protect highŌĆæwear areas, and make maintenance easy and predictable.

Proper belt tension is the foundation of effective power transmission. Binkelman stresses that correct tension keeps the belt in contact with the drive pulley, reducing slippage and uneven wear. MLT Group adds that incorrect tension is a root cause of multiple failure modes, including misalignment, slippage, and material spillage. Pit & Quarry points out that overŌĆætensioning can cause excessive shaft deflection, material fatigue, and premature failures, while underŌĆætensioning leads to drive pulley slippage, belt sag, and accelerated wear on pulleys and wing pulleys. IBT offers a practical tip for modular belting: adding a small amount of extra belt length to create one to four inches of catenary sag after the drive roller. That extra slack acts as a selfŌĆæadjusting tensioner, improving beltŌĆætoŌĆæsprocket engagement and compensating for thermal expansion or contraction.

Tracking and geometry are equally critical. EZG Manufacturing and Conveyors247 both describe belt tracking issues as common symptoms of deeper misalignment, uneven loading, or buildup. Coal AgeŌĆÖs discussion of conveyor geometry shows how steep or uneven inclines, abrupt transitions, and tight curves disrupt material flow and increase spillage, mistracking, and mechanical stress. Poor geometry forces drives to work harder, start against compacted or plugged material more often, and tolerate higher shock loads.

Transfer points are a highŌĆæimpact area where design and maintenance intersect. Coal Age and Pit & Quarry highlight that poorly designed transfer chutes increase material turbulence, spillage, dust, and wear on belts and components. Coal Age describes the use of discrete element modeling to visualize bulk material behavior in transfer chutes, identify areas of turbulence or buildup, and optimize chute shapes and trajectories. In a borate mine case study, MotionŌĆÖs engineering team, as reported in Coal Age, replaced worn skirt clamp systems and skirt rubber, added UHMW slider beds under load points to support the belt, and corrected scraper positioning and tensioning. After these changes, the mine documented dramatic reductions in airborne dust and product spillage, and expected significant reductions in premature idler failures and belt wear. For drive systems, that translates into smoother loading, fewer overload events, and reduced torque spikes.

Maintainability is not an afterthought; it should be baked into the design. Coal Age warns that when maintainability is overlooked, simple servicing tasks become timeŌĆæconsuming and hazardous. They recommend incorporating maintenance platforms around drive pulleys, walkways, handrails, adequate lighting, and easyŌĆætoŌĆæopen inspection panels. Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs maintenance guidance echoes this by emphasizing regular access to belts, rollers, and drives for inspection and lubrication. Conveyors247 and EZG Manufacturing give very similar practical prescriptions: daily visual inspections, regular cleaning to remove debris and spills, lubrication of bearings and chains according to manufacturer guidelines, and routine checks of belt tension and alignment.

The payoff of this discipline is substantial. MLT Group notes that structured preventive maintenance extends belt life, reduces unexpected downtime, and lowers repair costs, while documented preventive schedules and conditionŌĆæmonitoring tools such as vibration analysis and thermal imaging help detect developing issues early. Impomag quantifies the stakes with an example where one minute of unplanned downtime equated to about three hundred and fifty lost cases at forty dollars each, or roughly fourteen thousand dollars in lost opportunity. At that rate, a single halfŌĆæhour driveŌĆærelated line stoppage could represent over four hundred thousand dollars in missed throughput, even before overtime and recovery efforts are considered.

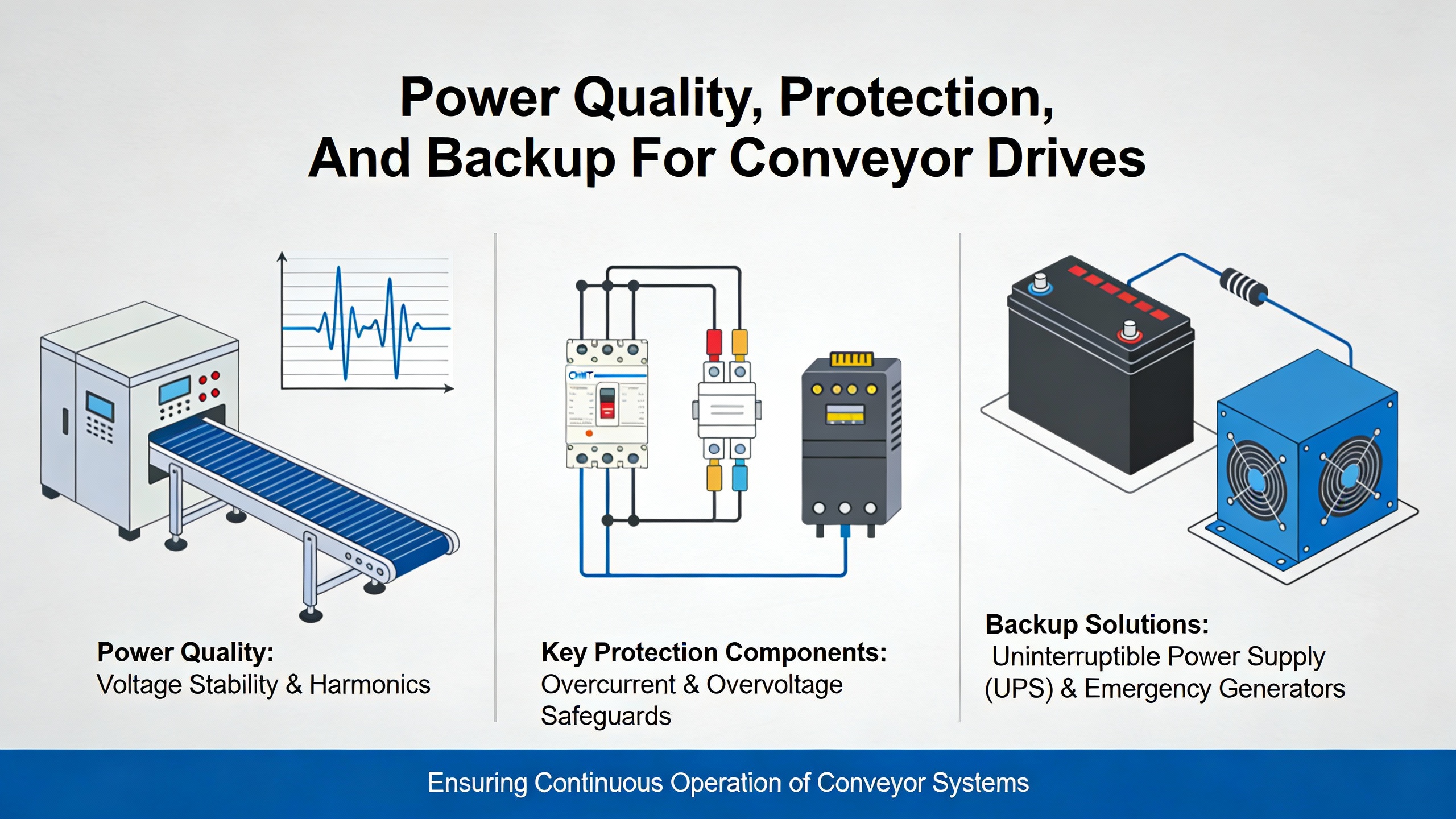

From a power systems standpoint, conveyor drives are missionŌĆæcritical loads with distinctive behavior. They combine large motors, often with variable frequency drives, significant inrush current if started across the line, and tight coupling to production flow. The maintenance and design sources make it clear that downtime is expensive and that conveyors run for long hours in tough environments. The remaining question is how to keep drive systems running when the power system misbehaves.

While the conveyor literature summarized here focuses more on mechanical and control aspects than on power protection, it consistently highlights the importance of continuous, reliable operation. Production Resources describes conveyors as core to modern material flow and supply chains. Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs maintenance guide notes that unplanned downtime can cost anywhere from about five thousand to fifty thousand dollars per hour, and more during peak season. Impomag points to situations where even a minute of downtime carries a fiveŌĆæfigure opportunity cost. Those figures are exactly the context in which UPS systems, powerŌĆæconditioning inverters, and wellŌĆæcoordinated protective relays earn their keep.

In practice, most facilities treat the conveyor system as several distinct electrical risk domains rather than as one monolithic load. The highŌĆæhorsepower motors driving long belt or roller runs often connect directly to the main distribution with appropriate motor protection. Variable speed drives for those motors must be coordinated with upstream breakers and fuses so that a brief voltage dip or fault on another branch does not immediately trip them offline. The control layer above that, including PLCs, sensors, zone controllers, and communication switches, is far lower in power but arguably more critical than a single motor. If a drive faults but control power and communications remain uninterrupted, the system can usually be restarted quickly and safely. If the control system itself collapses on every voltage event, recovery is slower, more manual, and more errorŌĆæprone.

That is why many reliability programs prioritize protecting control and communication power with UPS and powerŌĆæconditioned sources. Even a modest UPS can ride through short disturbances and give operators or automation sequences enough time to stop conveyors in a controlled fashion. When controls remain alive through a brief outage or sag, restart sequences are smoother, safety systems remain active, and troubleshooting is faster because diagnostic information is preserved. This approach aligns with the emphasis on diagnostic software, remote monitoring, and data analytics seen in Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs maintenance guidance and MLT GroupŌĆÖs discussion of advanced monitoring tools.

Another powerŌĆæside consideration is the interaction between drive technology and backup sources such as engineŌĆægenerators or static transfer switches. Variable frequency drives, servo systems, and highŌĆæefficiency motors can be sensitive to frequency and voltage variations and may present nonŌĆælinear loads to generators. Coordinating drive parameters, generator sizing, and any active frontŌĆæend or harmonicŌĆæfiltering equipment is essential. While the sources covered here do not delve into those details, the underlying theme remains: treat conveyor drive systems as critical loads during power system studies, not as an afterthought.

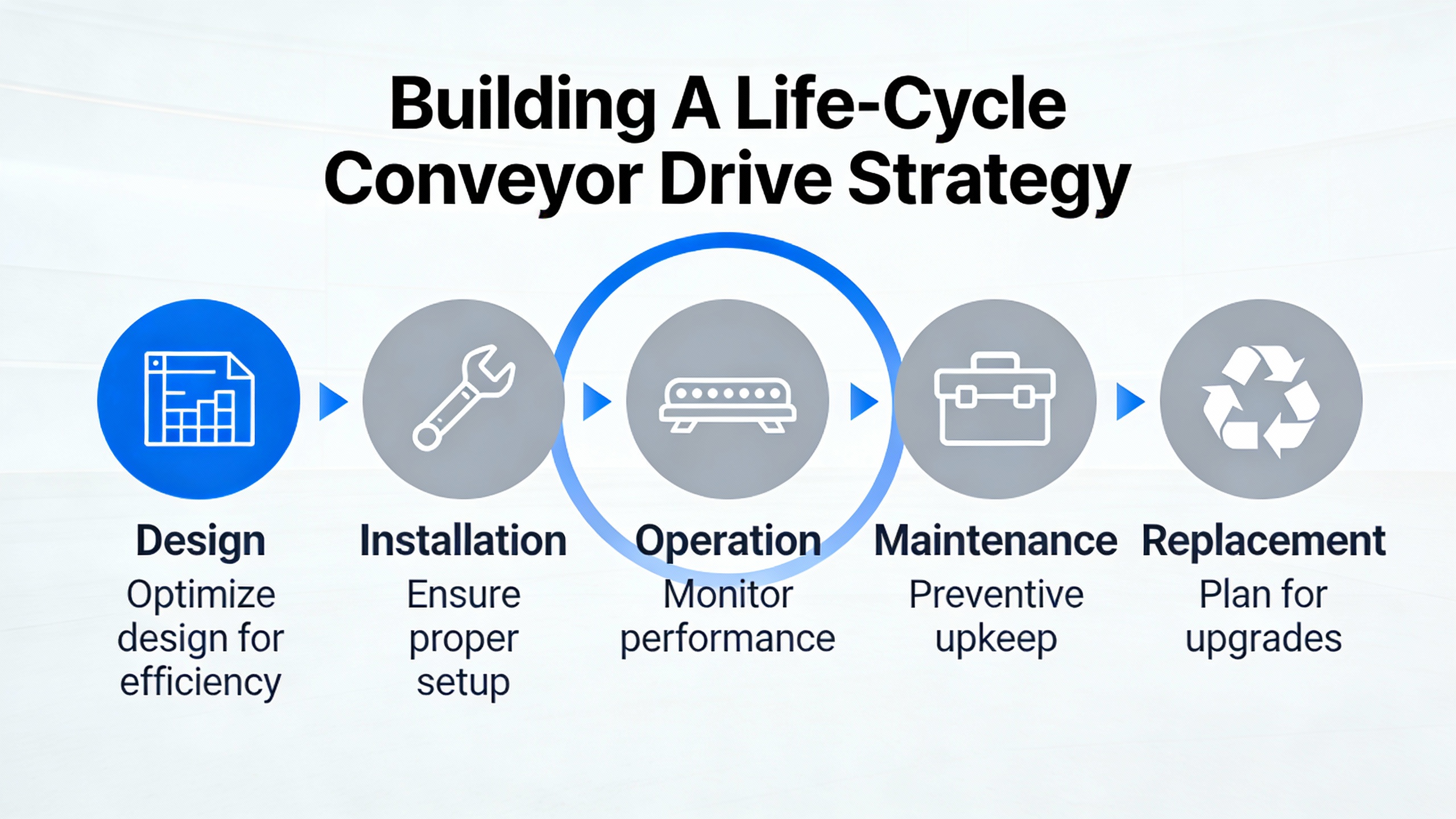

The final decision point is strategic rather than purely technical: how will you manage conveyor drives across their life cycle, from initial design through expansion, maintenance, and eventual replacement. The most successful practices in the conveyor literature share three traits: they integrate design and maintenance thinking from day one, they use data to refine maintenance and upgrades, and they engage both internal teams and external specialists.

Design and maintenance integration is visible in multiple sources. Coal Age explicitly frames maintainability as a design parameter, not a boltŌĆæon. Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs design guide couples layout and component selection with an explicit call for regular preventive maintenance once the system is installed. Production Resources and YFConveyor both stress that systems should be designed for adaptability, allowing retrofits and integration of new components or technologies without wholesale replacement. AEC Carolina recommends leaving room and structural provisions for future expansion so that additional drives, zones, or vertical paths can be added as product mixes evolve.

DataŌĆædriven refinement is the second trait. MLT Group advocates structured preventive maintenance with daily, weekly, monthly, and annual tasks, but also highlights the role of conditionŌĆæmonitoring tools and computerized maintenance management systems in optimizing service intervals. Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs maintenance guide on warehouse conveyors describes predictive maintenance using vibration, temperature, current, and tracking sensors to estimate remaining component life and trigger conditionŌĆæbased work orders. Element LogicŌĆÖs discussion of sortation system maintenance similarly calls for structured scheduling, clear procedures, and documentation, along with stocked spare parts to shorten repair times. Over time, data from these systems reveal patterns such as recurring failures in specific drive sizes or at particular transfer points, which can then be addressed through design changes, component upgrades, or control tweaks.

The third trait is collaboration. Many of the sources are themselves service or equipment providers emphasizing their expertise: AEC Carolina, Binkelman, EZG Manufacturing, Motion Conveyance Solutions, Davis Industrial, Lafayette Engineering, Speedrack West, and others all present themselves as partners in design, maintenance, or upgrades. Their advice is consistent: involve specialists who understand both conveyor mechanics and power and control systems when you face persistent tracking issues, frequent roller failures, overloads, or major structural wear. For drive systems in particular, there is value in bridging mechanical, electrical, and reliability perspectives. A conveyor specialist may optimize belt selection and transfer geometry; a power specialist can ensure that drives, UPS systems, protective relays, and backup sources are coordinated; and your inŌĆæhouse maintenance team can validate what is practical on the floor.

To make this more tangible, consider a retrofit scenario. A tenŌĆæyearŌĆæold conveyor line running fixedŌĆæspeed motors is experiencing increased stoppages due to belt wear, misŌĆætracking, and mechanical issues, and operations wants more throughput. EZG ManufacturingŌĆÖs guidance would lead you to examine belt condition, alignment, and roller health. Binkelman and Coal Age would have you revisit belt specification, tensioning, and component sizing. CiscoŌĆæEagle and IBT would push you to consider upgraded controls, sensors, and perhaps dynamic zone logic to avoid jams. From a power and reliability standpoint, this is also the ideal time to evaluate whether adding variable frequency drives, improving motor efficiency, and protecting control power with UPS support make sense. The retrofit becomes an opportunity to improve not just mechanical performance but also power quality resilience and maintainability.

A simple cost comparison underscores the stakes. If a line experiences just one unplanned halfŌĆæhour outage per week and the downtime cost is at the low end of Lafayette EngineeringŌĆÖs range, say five thousand dollars per hour, that single recurring issue carries an annual cost of around one hundred thirty thousand dollars. If the same line is closer to ImpomagŌĆÖs highŌĆævolume distribution example, where a minute of downtime costs about fourteen thousand dollars, the economics become even more compelling. In that context, investments in better drives, improved maintenance access, condition monitoring, and appropriate power protection are not luxuries; they are core reliability measures.

The table below summarizes how some of the main design and maintenance levers discussed across these sources influence conveyor drive performance.

| Design or Maintenance Lever | Primary Impact On Drives | Key Source Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Accurate material and product characterization | Correct motor and gearbox sizing, appropriate starting torque, realistic speed range | Coal Age on material properties, AEC Carolina and Macawber India on product specs |

| Belt and component selection matched to application | Stable traction, reduced slippage, compatible friction and wear characteristics | Binkelman on belt compounds, EZG Manufacturing on belt types, Nercon on spiral materials |

| Conveyor geometry and transfer design | Lower shock loads, fewer plug starts, smoother load profile | Coal Age on geometry and DEM, Pit & Quarry on transfer design |

| Variable speed drives and modern controls | Soft starts, adaptive speed, reduced energy use and mechanical stress | Coal Age on VFDs, Lafayette Engineering and YFConveyor on variable speed and energy efficiency, IBT and CiscoŌĆæEagle on automation |

| Preventive and predictive maintenance | Fewer drive stoppages due to belt, idler, and component failures, longer service life | EZG Manufacturing, MLT Group, Conveyors247, Lafayette Engineering maintenance guides |

| Power quality and control power protection | Reduced nuisance trips, faster recovery from power events, preserved diagnostics | Impomag and Lafayette Engineering on downtime cost context, MLT Group on monitoring and CMMS use |

WellŌĆædesigned conveyor drive systems sit at the intersection of good mechanical engineering, disciplined maintenance, and thoughtful power and control design. The industry guidance from conveyor and maintenance specialists is clear: understand your material and throughput, size and control your drives accordingly, protect highŌĆæwear areas, and make maintenance easy and predictable. From a power reliability perspective, treating conveyor drives and their controls as critical loads and planning for power disturbances is just as important as selecting the right belt or gearbox. When you align these elements, your conveyors stop being a constraint and start acting as a dependable, efficient backbone for the rest of your automation.

Leave Your Comment