-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

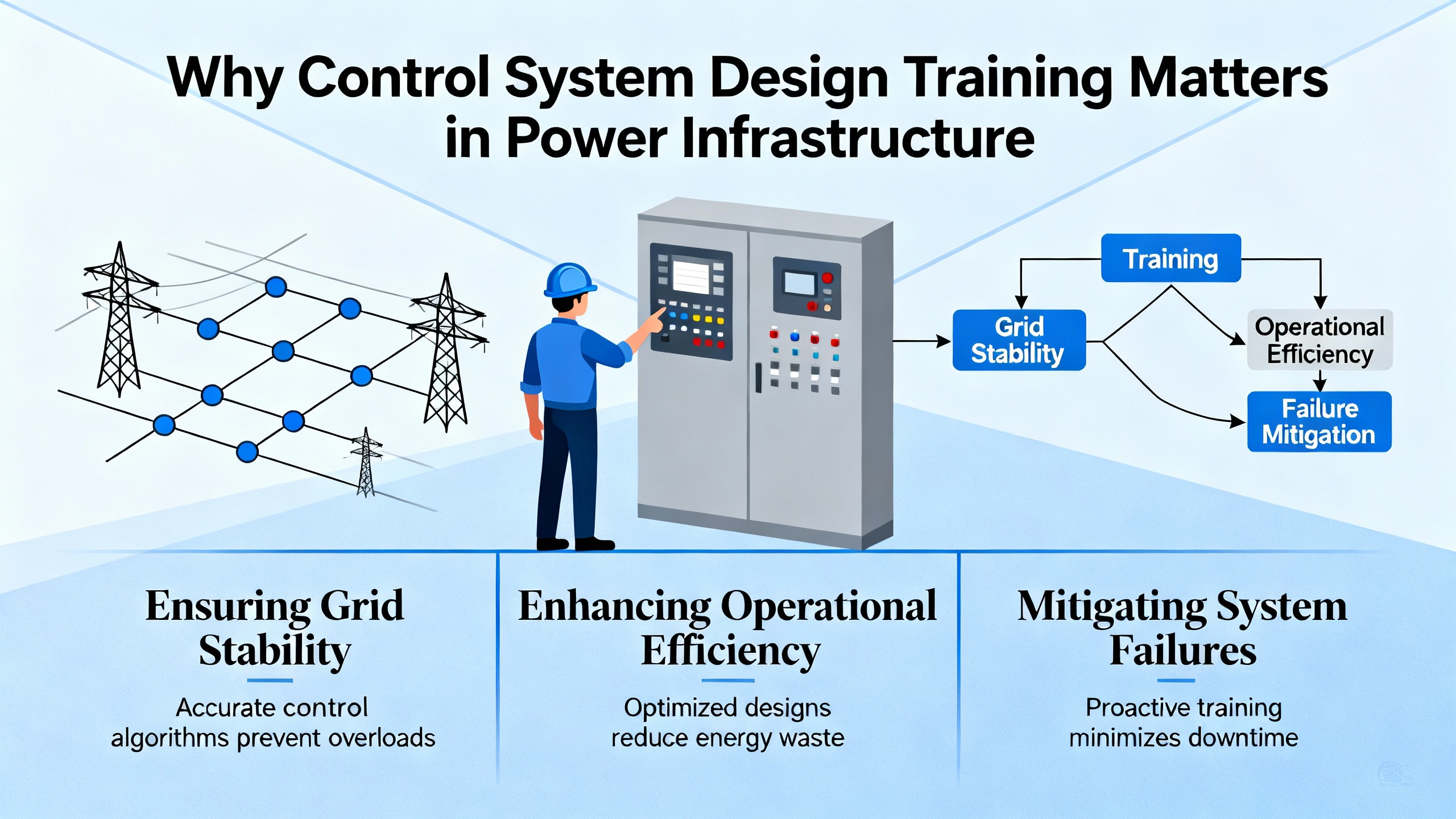

In industrial and commercial power systems, reliable control is the thin line between business continuity and cascading failures. Uninterruptible power supplies, static and rotary inverters, battery systems, and power protection schemes all depend on control logic that sees disturbances early, reacts appropriately, and fails safely. When that control logic is poorly designed or poorly understood, even premium hardware cannot compensate.

Control engineering is more than wiring up a few relays or copying a vendor function block. It is a discipline that combines system modeling, feedback theory, software engineering, and risk management. As multiple authors in modern systems engineering note, complex projects now demand holistic approaches that integrate engineering, project management, and systems theory over the entire life cycle rather than treating subsystems in isolation. That observation applies directly to large UPS plants, distributed inverter fleets, and critical power protection systems in hospitals, data centers, and manufacturing plants.

Recent highŌĆæprofile failures outside the power domain, such as the Boeing 737 Max control system crises discussed in Control Engineering Magazine, underline a hard truth. When automated control systems are safety critical, design discipline and adherence to best practices become matters of life and death. For a missionŌĆæcritical facility, a control design misstep can translate into lost production, equipment damage, or worse. Investing in serious control system design training is therefore not a luxury; it is a core reliability strategy.

In my work as a power system specialist and reliability advisor, I have seen teams that systematically train control engineers around sound design principles deliver cleaner startups, fewer commissioning surprises, and far more maintainable systems. The rest of this article distills best practices from that field experience and aligns them with guidance from sources such as Boston Engineering, ISA, Cornell University, and Trullion, with a particular eye on UPS, inverter, and power protection applications.

Before training can tackle advanced strategies like model predictive control or complex powerŌĆæsharing schemes, engineers need a shared foundation. Several sources, including Industrial Design Solutions and control theory tutorials, converge on the same basic architecture: sensor, controller, actuator, and process.

The sensor measures a relevant process variable, such as bus voltage, current, frequency, or transformer temperature. The controller compares that measurement to a desired setpoint and computes an output based on a control algorithm. The actuator then executes the decision by modulating a power electronic converter, operating a switch, or adjusting a mechanical device. The process is the physical system being controlled, for example the output of a UPS inverter feeding a critical bus.

The error signal is the difference between the setpoint and the measured variable; it is the input that drives most controllers. Developing intuition around this simple loop is critical. When a trainee can confidently identify the sensor, controller, actuator, and process for a static transfer switch, a battery charger, or a generator paralleling scheme, they are ready to move beyond cookbook configuration.

Another essential distinction is openŌĆæloop versus closedŌĆæloop control. OpenŌĆæloop systems operate without feedback and simply follow preset instructions; classic examples include timers that start a backup generator after a fixed delay. ClosedŌĆæloop systems, in contrast, continually measure outputs and adjust inputs in real time, such as an AVR maintaining generator voltage or an inverter regulating output under variable loads. Industrial Design Solutions emphasizes that closedŌĆæloop architectures provide higher accuracy and robustness in variable or safetyŌĆæcritical environments, which is exactly where most missionŌĆæcritical power systems operate.

Training programs that focus only on tool operation or vendorŌĆæspecific screens, without embedding these fundamentals, produce engineers who can configure but cannot design. This leads to fragile systems where any change requires vendor intervention and where emergent interactions between control loops are poorly understood.

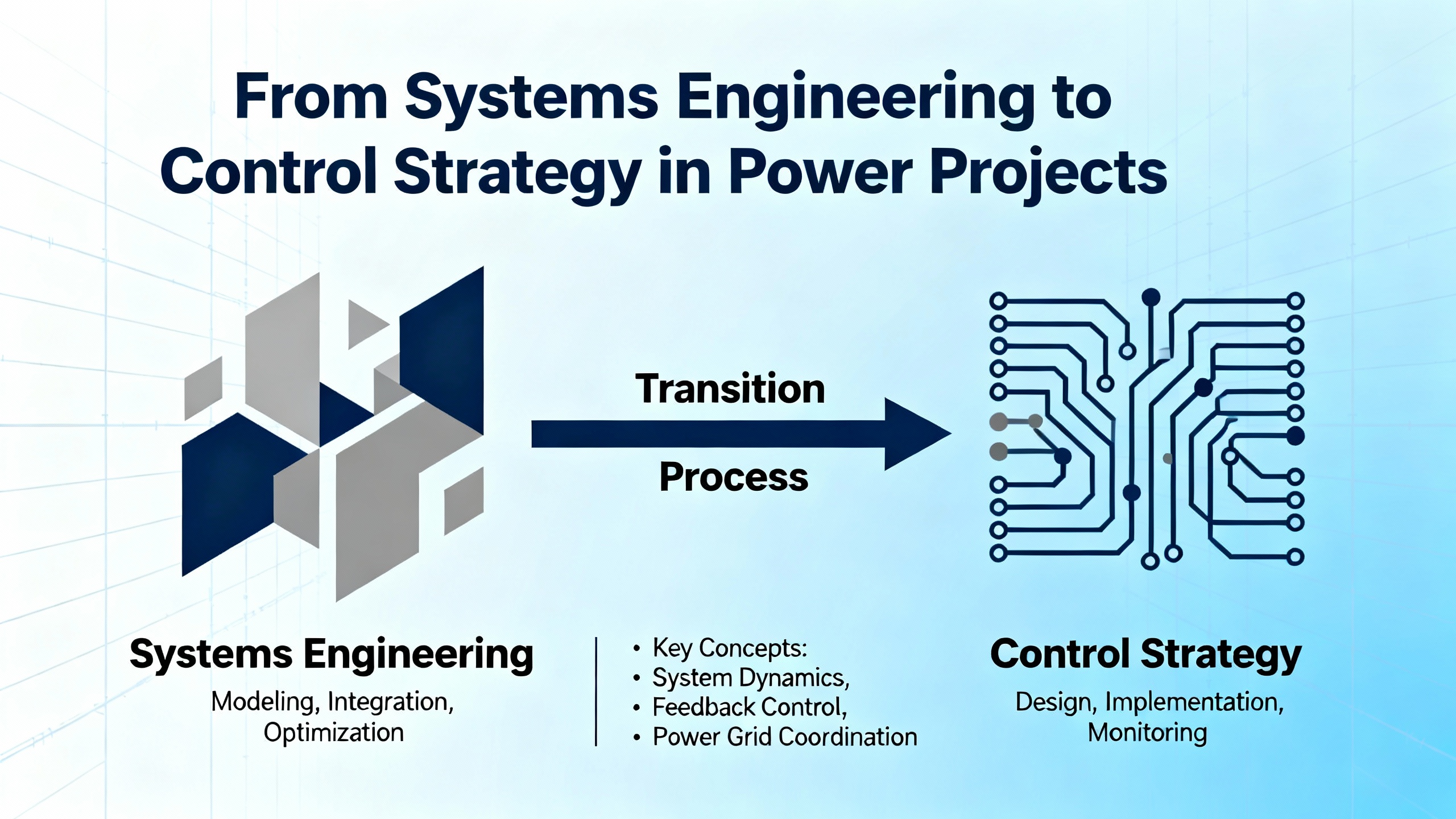

Systems engineering literature, such as the work highlighted by Aditya Sunjava and the detailed Quora discussion on control versus systems engineering, describes large systems as more than the sum of their parts. Control engineering focuses on individual automatic subsystems, like a UPS output voltage regulator, while systems engineering integrates many such subsystems into a complete solution that satisfies financial, regulatory, user, and environmental objectives.

In a critical power project, these objectives might include not just uptime and power quality, but also capital cost, operating cost, maintainability, and resilience to future changes in load profile or grid codes. Systems engineering emphasizes defining objectives clearly, engaging stakeholders early, and continually revisiting design assumptions. It also warns against the common tendency to rush through problem definition and dive straight into solutions.

Effective control system design training should explicitly teach this mindset. Engineers should learn to ask whether their UPS control scheme supports not only todayŌĆÖs load and topology but also expected growth, evolving cybersecurity constraints, and new operating modes such as islanded operation with renewables. This aligns with systems engineering guidance that a ŌĆ£satisfactory solution to the right problem is often better than an excellent solution to the wrong problem.ŌĆØ

Boston Engineering describes a control strategy as the set of rules, algorithms, and methods that manipulate a system so its output meets predefined objectives despite disturbances. In power systems, those objectives may include maintaining voltage and frequency within tight limits, sharing load between multiple UPS modules, managing battery charge and health, or coordinating transfer to bypass under fault conditions.

Training should present major control strategies not as abstract mathematics but as practical options with distinct tradeŌĆæoffs:

ProportionalŌĆæIntegralŌĆæDerivative control is ubiquitous. PID loops adjust outputs based on the proportional, integral, and derivative of the error. For example, a wellŌĆætuned PID controlling an inverterŌĆÖs output voltage can deliver excellent steadyŌĆæstate accuracy and rapid disturbance rejection. Training should cover how each term affects behavior, the pros and cons of aggressive tuning, and practical implementation issues such as actuator saturation and antiŌĆæwindup.

Model Predictive Control uses a dynamic model to predict future behavior and choose control actions that optimize a performance criterion over a time horizon. Boston Engineering notes that MPCŌĆÖs forwardŌĆælooking nature enables sophisticated decision making. For power converters or complex energy management schemes, MPC can in principle handle constraints and multivariable interactions better than simple loops, but it demands robust models and more computational resources.

OnŌĆæoff control is conceptually simple: a parameter is either above or below a threshold. Thermostatic control of a battery room HVAC system is the obvious example. In power systems, onŌĆæoff control can be adequate for noncritical auxiliary systems but is usually insufficient for core power regulation.

Fuzzy logic, stateŌĆæspace, feedforward, and adaptive control all play roles when systems are nonlinear, highly coupled, or subject to large disturbances. For example, feedforward compensation can be used in a UPS to anticipate the effect of a large step load, using information about the load transfer, before the main feedback loop has time to respond.

Control strategy selection should be taught as a design tradeŌĆæoff rather than an academic exercise. Boston Engineering emphasizes that choice depends on system complexity, required performance, and detailed objectives, and that poor choices can delay projects or cause integration problems. Training that walks through realistic power system case studies, comparing what happens when a UPS output regulator uses simple proportional control versus a carefully tuned PID with feedforward, is far more powerful than abstract block diagrams alone.

TonexŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Fundamentals of Control Systems EngineeringŌĆØ and curated control systems courses on platforms such as Coursera highlight the analytical backbone of modern control engineering. Participants learn to model dynamic systems using differential equations, transfer functions, and stateŌĆæspace representations, and to analyze stability and performance using timeŌĆædomain and frequencyŌĆædomain tools.

In the context of power systems, this analytical training should be anchored in familiar equipment. Instead of generic massŌĆæspringŌĆædamper examples, course modules can model the step response of a UPS inverter under a load change or the dynamic behavior of a generatorŌĆæUPS combination during synchronization and transfer. Concepts such as root locus, Bode plots, and gain/phase margins become immediately relevant when trainees see how they link to inverter control stability or voltage regulation under nonŌĆælinear loads.

Tonex also emphasizes stateŌĆæspace techniques, controllability, observability, and even introductory optimal and model predictive control. While not every engineer will implement MPC in a UPS, exposure to these methods prepares teams for future architectures where battery storage, renewables, and gridŌĆæinteractive inverters are orchestrated by advanced controllers.

Training programs that combine these mathematical foundations with handsŌĆæon simulation exercises, as described in Tonex and Coursera outlines, help engineers move from ŌĆ£parameter twiddlingŌĆØ to deliberate control design.

Internal control guidance from sources such as eCampusOntario, Cornell University, Diligent, and Trullion describes organizational control systems as structured sets of policies, procedures, and monitoring activities that safeguard assets, ensure reliable reporting, and maintain compliance. Although these sources focus on financial and governance controls, the underlying principles map directly onto engineering control systems.

A wellŌĆædesigned power control system should also be built on explicit objectives, a structured risk assessment, and appropriately strong controls where risk and impact are highest. eCampusOntario emphasizes establishing clear, measurable control objectives, identifying and assessing risks, and designing preventive, detective, and corrective controls. Cornell University extends this by describing preventive measures such as segregation of duties and authorization, detective controls like reconciliations and exception reporting, and the importance of rootŌĆæcause analysis when discrepancies are found.

Translating that mindset into power engineering training means teaching engineers to think beyond ŌĆ£Does the UPS maintain voltage?ŌĆØ toward ŌĆ£What could go wrong and how will we detect, prevent, or correct it?ŌĆØ For example, preventive technical controls might include redundant sensors on critical measurements or interlocks that prevent unsafe switching sequences. Detective controls could be event logs, trend analyses, and diagnostic alarms that identify incipient failures in fans, capacitors, or batteries. Corrective controls include automated safe shutdown sequences, predefined fallback modes, and documented recovery procedures.

Risk appetite and risk tolerance, concepts emphasized in internal control literature, are equally relevant. A data center might have nearŌĆæzero tolerance for unplanned power interruptions but greater tolerance for operating closer to equipment thermal limits. Training should help engineers articulate these preferences and translate them into control design decisions, such as how conservative to be with overload thresholds or how aggressively to shed noncritical loads during a disturbance.

Control frameworks also stress continuous monitoring and refinement. Internal control systems are not ŌĆ£set and forgetŌĆØ; they evolve with the business, regulatory landscape, and technology. Likewise, control design training should teach engineers to plan for periodic review of control performance, to incorporate operational feedback, and to adjust algorithms and alarm thresholds in a controlled manner as conditions change.

ISAŌĆÖs discussion of design principles for complex process control offers strong warnings against overcomplication. Complex processes are not defined only by how many signals exist, but by tightly coupled, nonlinear dynamics with long time constants. In such environments, every additional controller and sensor adds potential instability and failure modes.

ISA recommends using the minimum number of controllers consistent with performance goals and relying on the minimum number of sensors necessary for robust control, because instrumentation is often the weakest, most failureŌĆæprone element. Cascade control should be deployed only when it significantly improves performance, such as linearizing a nonŌĆælinear response or splitting a very slow time constant. Similarly, strategies where a single manipulated variable attempts to satisfy several competing objectives should be approached with great caution in highly coupled systems.

For UPS and inverter systems, this principle suggests questioning the urge to add extra nested loops and complex override logic without a clear benefit. Training should show, through examples, how an overly complicated set of interdependent loops can create oscillations or unpredictable behavior when a sensor drifts or a breaker status is misread. By contrast, wellŌĆædesigned architectures that leverage the natural dynamics of the process, avoid double control of the same variable, and maintain clear separation between control roles tend to be more stable and easier to troubleshoot.

ISA also introduces a ŌĆ£negentropic, lean developmentŌĆØ principle. Over the course of commissioning and optimization, total control code volume should ideally stay constant or shrink, because fixes replace or simplify logic instead of accumulating layers of patches and dead code. This aligns closely with lean engineering thinking: designs that simplify the overall system and its codebase are often the most robust, while mathematically elegant schemes that increase complexity should be treated with skepticism.

Embedding these ideas into training helps create engineers who instinctively look for the simplest design that works and who resist adding complexity just because tools or hardware make it easy.

CrossCoŌĆÖs vendorŌĆæneutral guidance on control system programming spells out a set of best practices born from decades of field experience. These principles are especially relevant in power control systems where logic spreads across PLCs, distributed control systems, inverter firmware, and HMI platforms.

First, define an overall structure and ŌĆ£mapŌĆØ for the application. Engineers should be trained to design and document how functions, variables, and HMI elements are segmented and organized so that others can follow the design. Supporting documentation should state functional requirements and programming standards and, ideally, live alongside the code in the form of standard libraries and templates.

Second, plan for future expansion and change without indulging in uncontrolled overdesign. CrossCo recommends segmenting memory with room for each data type, stressŌĆætesting organizational schemes, and reviewing them with peers. In power systems this might mean reserving clear namespaces and address ranges for future UPS modules, generator additions, or new measurement points, rather than scattering them wherever free space exists.

Third, develop resource awareness. Controllers have finite CPU, memory, and communication bandwidth. The article advises explicit loading tests that push systems well beyond expected scope to understand headroom, instead of adding layers of abstraction blindly. For central power controllers that must handle many signals, breaker states, and transfer sequences, this awareness is crucial.

Fourth, reuse code intelligently. Common logic, such as motor starts, breaker interlocks, or alarm handling, should exist as wellŌĆæparameterized functions or blocks, not as repeated handŌĆæcoded sequences. This reduces memory usage, accelerates development, and decreases errors when changes are needed.

Finally, ensure consistency in design patterns, naming, and comments. CrossCo emphasizes that comments should explain why things are done, while the code itself should show how. Temporary logic should be clearly segregated and cleaned up once decisions are made. In power systems where maintenance teams and future vendors must read and trust control code, this level of discipline directly affects reliability and safety.

Control system design training that treats these software practices as firstŌĆæclass topics, not afterthoughts, produces systems that are far easier to operate, audit, and evolve.

The Boeing 737 Max case, as analyzed by Control Engineering, has become a cautionary example for all safetyŌĆæcritical control systems. The article explains that updated designs now compare multiple sensor inputs, constrain automatic corrections, and allow pilots to override the system. It also highlights organizational changes aimed at elevating safety culture and empowering engineers to raise concerns.

Power control environments are different, but the underlying lessons are identical. Training should engrain a few nonŌĆænegotiable principles.

Control systems must be designed to fail safely. In a UPS plant, that may mean defaulting to a known safe mode such as static bypass under certain fault conditions, with clear indications to operators. Operators must always have a clear view of what is happening, which calls for humanŌĆæmachine interfaces that show operating modes, alarms, sensor health, and the status of major breakers without ambiguity. Alarms should guide action, not overwhelm users with noise.

Single points of failure should be avoided, especially where their failure could lead to catastrophic outcomes before human intervention is possible. Redundant sensors, diverse measurement technologies, and voting logic, applied carefully, can significantly reduce risk. Training should include case studies where reliance on a single sensor or unverified assumption led to severe incidents.

Cultural elements also matter. The Control Engineering article notes the importance of listening to trained control engineers and experienced operators, upholding standards and certifications, and protecting whistleblowers. Training programs should explicitly address the professional responsibility engineers carry when working on power control systems that can affect health, safety, and large financial exposures. This includes encouraging engineers to speak up when they see unsafe logic, missing interlocks, or inadequate testing.

Henderson Engineers describe how they implemented innovative control system design ideas by treating their initiative like a real project. They define the idea clearly, resource it appropriately, establish a process, build a roadmap, and cultivate a supportive culture. They also adopted a hybrid project management approach that blends traditional waterfall clarity about scope and time with agileŌĆÖs iterative development and frequent feedback.

This approach fits control design training remarkably well. Instead of a oneŌĆætime classroom event, training should be structured as a sequence of short, focused projects or ŌĆ£sprints,ŌĆØ each delivering a small but tangible piece of capability. For instance, one sprint might focus on modeling and tuning the output voltage loop of an inverter. A later sprint could address alarm strategy for a battery system, using operator feedback to refine thresholds and messages.

HendersonŌĆÖs use of concepts like stories, epics, and initiatives can be adapted directly. A training initiative might aim to ŌĆ£create a uniform control design and programming standard for all critical power systems.ŌĆØ Epics might include developing standard templates and libraries, building a catalog of common control modules, and training engineers across disciplines. Stories become specific tasks, such as ŌĆ£implement and review a standard UPS transfer sequence blockŌĆØ or ŌĆ£add structured alarm handling to the generator start sequence.ŌĆØ

By making training projectŌĆæbased and iterative, organizations keep it connected to real work, encourage crossŌĆæfunctional collaboration, and foster the culture of innovation and continuous improvement that Henderson Engineers link to better client experience.

A wellŌĆædesigned training program for control engineers in industrial and commercial power should combine content depth with delivery flexibility. It should address foundational theory, systemŌĆælevel thinking, detailed implementation practices, and governance.

A practical way to organize such a program is around a set of recurring themes. First, start with fundamentals and modeling, covering sensors, actuators, feedback, openŌĆæ and closedŌĆæloop behavior, and basic modeling of dynamic systems, with examples anchored in UPS and inverter applications. Second, move into control strategies and tuning, using the catalogue of strategies discussed by Boston Engineering and analytical techniques from Tonex and similar courses. Third, address risk and internal control thinking, borrowing concepts from financial internal control frameworks to structure engineering decisions around risk assessment, preventive and detective controls, and continuous monitoring.

Fourth, delve into control software and humanŌĆæmachine interface design, using CrossCoŌĆÖs guidance to teach code structure, reuse, commenting, and cleanŌĆæup, and using the Boeing and ISA cases to highlight human factors and failŌĆæsafe behavior. Fifth, incorporate verification, validation, and design control concepts. ComplianceQuestŌĆÖs discussion of design controls in medical devices, although focused on regulated health products, shows how rigorous design documentation, traceability from requirements to tests, and integration with supplier management and quality systems reduce risk and rework. Power system OEMs and integrators can adopt similar practices even when not mandated by regulation.

Finally, emphasize lifeŌĆæcycle thinking and change management. Internal control guidance from Diligent and Trullion stresses that controls must evolve with the organization and are supported by regular assessments, monitoring, and documentation. For power systems, that translates into structured approaches for updating control logic when equipment is upgraded, loads change, or new compliance requirements emerge, including clear documentation, testing, and communication to operations.

Formal courses and credentials can help structure and benchmark this training. The NCEES PE exam in Control Systems is designed to measure minimum competency after several years of practice. Its specifications outline a broad body of knowledge, including modeling, stability, feedback, and implementation, which can serve as a useful checklist. Specialized courses, such as TonexŌĆÖs fundamentals offering, provide intensive introductions or refreshers in analytical methods and modern control strategies. Curated online courses are useful supplements, offering flexible access to topics such as computational modeling, automation, and advanced control.

Different training modes bring different strengths, and organizations often combine them. The following simple comparison illustrates this.

| Training mode | Key strengths | Limitations | Best suited for | | InŌĆæhouse workshops anchored in current projects | Highly relevant, uses live systems and data, promotes crossŌĆædisciplinary collaboration | Requires internal experts and dedicated time, may be uneven in depth | Teams working on large UPS or inverter projects that need immediate impact | | External technical courses and certifications (for example, PE review, vendorŌĆæneutral fundamentals) | Structured curricula, proven coverage of essential topics, external benchmarking | Less tailored to specific company platforms, time away from work | Engineers building foundational competence or preparing for formal licensure | | Online courses and simulations | Flexible pacing, broad topic range, good for analytical skills and tools | Risk of low completion without structure, variable quality | Individuals building specific skills, such as modeling or advanced control methods |

The most effective programs tend to blend these approaches, using inŌĆæhouse projects to anchor theory from external courses and online modules.

From an internal control perspective, any system of policies and activities should be monitored and evaluated. The same applies to engineering training. Guidance from Diligent, Trullion, and Cornell University on evaluating internal control effectiveness can be adapted directly.

Organizations can define what ŌĆ£successŌĆØ means for control system design training. Common dimensions include improved reliability, reduced commissioning issues, fewer late design changes, better audit outcomes, and higher operator confidence. Just as internal controls are tested through reconciliations, walkthroughs, and data analytics, training impact can be examined by reviewing change logs, incident reports, and project retrospectives.

It is important to treat this assessment as an ongoing process rather than a oneŌĆætime survey. As technology, standards, and organizational objectives evolve, training needs will also shift. This echoes internal control recommendations that risk assessments, monitoring, and control refinement should be continuous, not episodic.

A practical technique borrowed from internal control evaluation is the ŌĆ£control selfŌĆæassessment,ŌĆØ where process owners reflect on whether designed controls are operating as intended. Control system design training can include similar selfŌĆæassessments, prompting engineering teams to periodically review whether their design practices still align with current best practices, whether documentation is kept current, and whether the actual control behavior in the field matches design intent.

Several recurring pitfalls undermine control design training in power organizations.

One is treating training as a oneŌĆætime awareness session. Without repetition, projectŌĆæbased exercises, and links to real deliverables, concepts like riskŌĆædriven design, lean architectures, or robust code practices do not stick. Systems engineering practitioners warn that the art of systems methodology is best learned through experience and team projects, not just textbooks.

Another pitfall is failing to integrate nonŌĆætechnical stakeholders. Internal control literature emphasizes engaging management, department heads, and external partners to ensure buyŌĆæin and clarity of roles. In the control design context, not involving operations, maintenance, and safety teams leads to control schemes that look elegant on paper but clash with realŌĆæworld practices, alarm fatigue, and unclear responsibilities in abnormal situations.

A third pitfall is underestimating instrumentation and data quality. ISA describes instrumentation as the weakest link in many control systems. Training that focuses solely on controller tuning and logic, without emphasizing sensor selection, placement, calibration, and diagnostics, leaves a critical gap. It also increases the risk that complex algorithms are built on unreliable measurements.

Finally, there is a tendency to focus only on the initial life of a system. The Quora discussion on systems engineering notes that this shortŌĆæterm view leads to components and subsystems that cannot accommodate societal or technological changes, causing early obsolescence. Training should therefore include lifeŌĆæcycle planning, modular designs, and disciplined change management to keep control systems aligned with evolving requirements.

How much theory do power control engineers really need? Engineers working on UPS, inverters, and power protection equipment need enough theory to understand stability, dynamic response, and the implications of different control strategies. Sources such as TonexŌĆÖs fundamentals course and the NCEES PE exam outline suggest that a solid grounding in feedback, modeling, and classical control methods is essential. However, this theory is most effective when paired with handsŌĆæon projects based on actual power equipment and scenarios.

Should we standardize on one control strategy, like PID, for everything? PID remains a workhorse and is appropriate for many loops, as Boston Engineering notes. However, the choice of strategy should be deliberate and contextŌĆædependent. Simple onŌĆæoff control may be sufficient for some auxiliary functions, while more sophisticated strategies such as feedforward or model predictive control may be justified for complex, constrained, or multivariable problems. Training should teach engineers when a simple approach is robust enough and when a more advanced strategy is warranted.

Where do internal controls and governance fit into technical training? Internal control frameworks from Cornell University, Diligent, and Trullion show that robust processes and clear documentation are critical for any system handling significant risks. For power control, integrating these concepts into technical training means emphasizing traceability from requirements to logic and tests, clear documentation of assumptions and design decisions, and structured processes for monitoring, change management, and continuous improvement.

Robust control system design is at the heart of reliable power infrastructure. Training that blends solid control theory, systems engineering mindset, rigorous software practices, and internal control disciplines gives engineers the tools to design, implement, and maintain safe, resilient UPS, inverter, and protection systems. For organizations that depend on continuous power, investing in this kind of training is one of the most costŌĆæeffective reliability measures available, and one that pays dividends throughout the life of every project.

Leave Your Comment