-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Commercial facilities are under pressure from every direction: rising energy prices, aggressive sustainability goals, and business models that rely on alwaysŌĆæon operations. As a power system specialist, I see the same pattern in almost every portfolio review. The HVAC plant, lighting, and power distribution all have some level of control, but they operate as islands. Facility teams are buried in alarms, yet they still get surprised by demand spikes, comfort complaints, and power quality issues.

Integrated building automation is how you turn that chaos into a coordinated system. When done well, it not only trims energy use and carbon; it also strengthens power reliability, supports UPS and inverter strategies, and gives you a clear line of sight from the grid connection down to individual loads.

This article walks through how to design and operate integrated automation for smart commercial buildings, with a particular focus on electrical systems and power protection.

Multiple independent research efforts converge on the same conclusion: modern automation is one of the highestŌĆæimpact levers for existing commercial buildings.

Schneider Electric reports that buildings account for roughly 37% of global COŌéé emissions and that about 70% of a typical buildingŌĆÖs carbon impact occurs during operation rather than construction. Because around half of todayŌĆÖs buildings are still expected to be in use in 2050, Schneider Electric estimates that roughly 85% of global building stock must be retrofitted to meet climate targets, and they cite automationŌĆædriven building management systems as capable of cutting energy use and carbon emissions by up to 35% without sacrificing air quality or comfort.

CIS Industries describes wellŌĆædesigned building automation systems, or BAS, as centralized digital platforms that monitor and control HVAC, lighting, security, and energy management. Their experience shows that commercial properties can see up to about 30% reductions in energy consumption when a BAS is properly designed and tuned, mainly by aligning operation with real occupancy and conditions instead of fixed schedules.

Eptura highlights a 60ŌĆæday study of IoTŌĆæenabled floors where electricity use dropped by 20%, water by 23%, and natural gas by 25%. At portfolio scale, RasMech cites a U.S. Department of Energy study finding average energy savings of 29% across commercial buildings that implemented BAS, with some building types, such as secondary schools and standalone retail, seeing more than 40% savings. Those gains were mostly from better HVAC control through setpoint adjustments, reduced minimum airflow, and occupancyŌĆæbased strategies.

These numbers matter for reliability because every kilowattŌĆæhour you do not waste is one you do not have to deliver through your switchgear, UPS, or generator. Lower and more predictable loads simplify power system design, extend battery rideŌĆæthrough, and reduce stress on distribution equipment.

Many commercial facilities already have a building management system. Smarter Technologies describes a BMS as a computerŌĆæbased system that monitors and manages mechanical and electrical services such as power, elevators, lights, access control, ventilation, heating, and airŌĆæconditioning. These systems emerged in the 1960s and have accreted layers of proprietary protocols and controls over decades.

In a traditional setup, the BMS mostly helps the facility manager watch for problems and perform basic HVAC and lighting control. As energy and sustainability expectations rose, this model started to fall short. The same Smarter Technologies guidance positions a smart building as the next generation of that BMS: one that uses integrated hardware, realŌĆætime data, twoŌĆæway communication, IoT sensors, analytics, and cloud computing to create an automated, sustainable, healthŌĆæconscious ecosystem rather than a collection of separate subsystems.

Spacewell defines a building automation system as a centralized, computerŌĆæbased platform that monitors and controls HVAC, lighting, security, and other building systems using sensors and controllers. They emphasize that when BAS is integrated with broader energy management systems and renewables, such as rooftop solar, it becomes a key tool for both energy reduction and emission mitigation, while also supporting occupant wellness and green building certifications.

Zenatix and Neuroject expand that picture to facility IoT. They describe modern automation architectures with field devices such as sensors and actuators connected via gateways and open protocols like BACnet and Modbus. These gateways push data over secure wired, WiŌĆæFi, or cellular links into cloud platforms for analytics and control. That architecture allows you to retrofit existing buildings without ripping out all legacy controls and at the same time add granular metering, occupancy sensing, and condition monitoring.

In practice, when you walk a modern plant room in a smart building, you see this evolution. The BMS screen is no longer just a readŌĆæonly map of air handlers and boilers. It is a live picture of electrical loads, UPS status, HVAC performance, lighting zones, and alarms, tied together with trend data and automated rules that act on that data.

Different vendors name their platforms differently, but the highest returns come when several critical systems are integrated so they behave like one coordinated machine.

HVAC and ventilation sit at the top of that list. Neuroject notes that HVAC can represent up to around 40% of a buildingŌĆÖs total energy consumption, and that IoTŌĆæenabled HVAC with smart thermostats and occupancyŌĆæbased ventilation can cut HVAC energy use by about 20 to 25%. CIS Industries explains how BAS optimizes HVAC using realŌĆætime occupancy, outdoor weather, and timeŌĆæofŌĆæday patterns so that conditioning occurs only where and when needed. Tyrrell Analytics recommends going beyond fixed schedules by using demandŌĆæcontrolled ventilation based on COŌéé or occupancy sensors, which improves both efficiency and indoor air quality.

Lighting is the second major target. Neuroject reports that IoT lighting control using connected fixtures and occupancy sensors can cut lighting energy by 30% or more compared with conventional alwaysŌĆæon lighting. Spacewell adds that automation turns lights off in unoccupied spaces, dims in response to daylight, and extends equipment life, while GSAŌĆÖs guidance on lighting echoes the principle of lighting only what you need, when required, at the lowest suitable intensity, with efficient LED technology as the default choice.

Security and access control increasingly operate through the same automation backbone. Neuroject describes IoTŌĆæbased security that unifies smart locks, card readers, cameras, and motion sensors into a central platform for monitoring and remote control. Digi explains how integrating CCTV, access control, and alarms into an IoT framework allows centralized monitoring, faster incident response, and stronger physical and cyber security.

On the electrical side, Schneider Electric highlights a critical but sometimes overlooked outcome of integrating power management with the BMS. By bringing realŌĆætime power data into the building automation platform, facility teams can manage nonŌĆæcritical loads, detect abnormal electrical patterns, validate energy savings, and reduce risks to power reliability and uptime. Spacewell and Zenatix similarly emphasize granular energy monitoring with smart meters and submeters at building, floor, or equipment level to track consumption, peak demand, and deviations from expected patterns.

GSAŌĆÖs federal guidance adds plug loads to the list. In a typical office, they note that equipment plugged into outlets, such as computers and copiers, can account for around 30% of electricity use. In minimally codeŌĆæcompliant buildings, plug loads may reach about a quarter of total energy consumption and can exceed half of total energy use in highly efficient buildings where HVAC and lighting are already optimized. Without automation and policies to manage those loads, they quickly erode the gains you make elsewhere.

When these systems share data and control, you gain a powerful capability: you can decide, in real time, which loads are essential and which are flexible, and coordinate HVAC, lighting, plug loads, and even production equipment with your power system, UPS, and generator strategy.

The concept of integration can feel abstract, so it helps to visualize the daily working environment of a facility team in an automated building.

Matterport describes smart building IoT combined with digital twins, where photorealistic, navigable 3D models are linked to live sensor data. Operators see not just a trend line, but the actual equipment in a model of the plant room, with data overlays showing temperatures, flows, and electrical parameters. They report that this approach can cut training time for critical operations by about half and reduce downtime by around 25% when multiple subsystems are managed from a single 3D interface.

Tecknoworks offers a complementary perspective from a large realŌĆæestate brand that deployed an AzureŌĆæbased automation solution. Their system gives tenants live energyŌĆæusage monitoring, supports modular, cloudŌĆæbased rollouts for new buildings, and uses a payŌĆæasŌĆæyouŌĆægo platform that automatically scales and provides geographic redundancy. To keep performance and costs in check, APIs preŌĆæprocess readings on arrival so that heavy analytics are not pushed into storage.

Across these examples and others from Spacewell, Eptura, and Digi, the operational pattern is similar. Sensors collect realŌĆætime data on energy use, occupancy, and environmental conditions. Controllers and analytics engines interpret that data to adjust HVAC and lighting, issue work orders, or trigger fault detection. Operators and service providers see the same information via dashboards, mobile apps, or digital twins and can intervene when needed. All of this sits on a foundation of interoperable protocols, secure networks, and clear automation rules.

From a power systems perspective, that last point is crucial. Trending data from BAS and IoT platforms gives you the factual basis for rightŌĆæsizing UPS systems, setting realistic rideŌĆæthrough times, and identifying which loads can be shed early during a disturbance versus which must stay online until the last watt is drawn from batteries.

Tyrrell Analytics frames building automation rules as standards and guidelines that connect sensors, actuators, controllers, and management systems to optimize energy efficiency and control from design through commissioning and beyond. The most resilient automation strategies start with clear objectives rather than technology wish lists.

One primary objective is efficient, reliable environmental control. Tyrrell Analytics recommends defining explicit goals such as reduced energy consumption, extended equipment life, and improved comfort before writing any rules. They then emphasize energyŌĆæefficient scheduling so that HVAC and lighting follow occupancy patterns and time of day instead of running at full capacity around the clock. Enervise illustrates how tuning thermostat start times and setpoints based on realŌĆætime occupancy and outdoor weather can cut summer energy use without sacrificing comfort, and they cite U.S. Department of Energy guidance that clogged air filters alone can increase energy consumption by about 15%.

A second objective is healthy, comfortable spaces. Spacewell notes that BAS can support personalized control of temperature, lighting, and ventilation, along with indoor air quality monitoring, to maintain healthy and productive environments. Neuroject and CIS Industries both highlight demandŌĆæcontrolled ventilation that adjusts airflow based on occupancy or COŌéé levels, which improves air quality while avoiding unnecessary fan and conditioning energy.

A third objective is lower operational risk. RasMech emphasizes alarm functions in BAS that detect abnormal conditions and notify staff quickly, supporting rapid response to safety, security, and operational issues. Tyrrell Analytics and Spacewell both describe how predictive maintenance based on sensor data can detect deviations from normal equipment performance and trigger interventions before failures occur. MatterportŌĆÖs case studies show predictive analytics reducing project planning costs and extending equipment life in industrial settings.

These objectives must be balanced against a critical warning from DŌĆæTools and GSA. Poorly configured BAS can waste energy rather than saving it, as seen in Rush University Medical Center where stuck valves and faulty sensors caused the system to increase energy use. GSAŌĆÖs guidance also stresses that upgrades and replacements must be planned carefully to avoid negative impacts on occupant health, comfort, or job performance. In other words, automation amplifies both good and bad design decisions. That is why commissioning, retroŌĆæcommissioning, and periodic reŌĆætuning are as important as the initial installation.

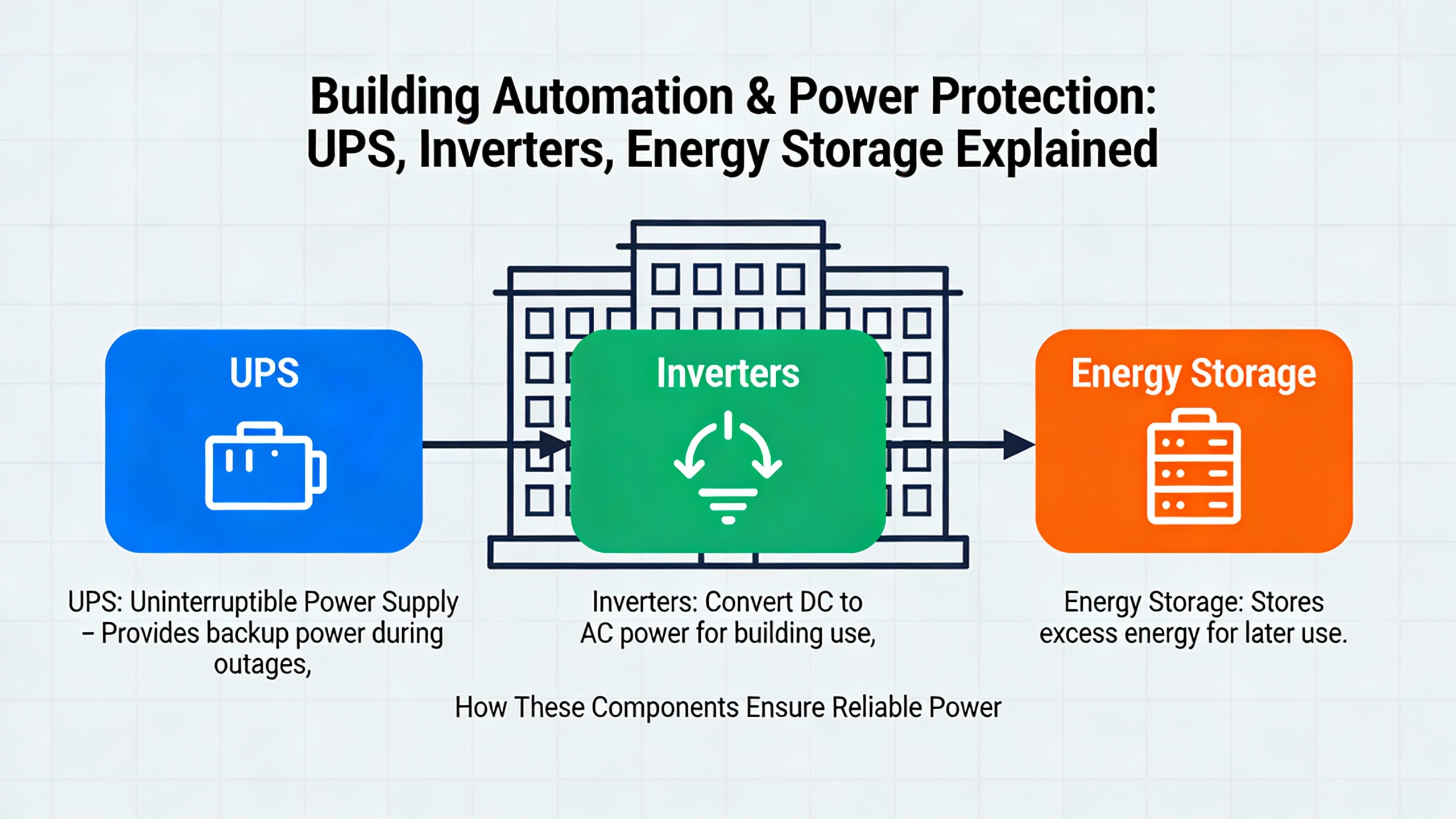

For missionŌĆæcritical facilities, the conversation about building automation is inseparable from power quality and resilience. You are not just chasing kilowattŌĆæhours; you are protecting data centers, operating rooms, process lines, and life safety systems.

Schneider Electric underscores the value of integrating power management systems with the BMS to improve electrical system efficiency. When power meters, panel monitors, and load controllers feed into the automation platform, operators can see how nonŌĆæcritical loads behave during peaks, detect abnormal electrical patterns, and validate energyŌĆæsaving projects. This same visibility can drive coordinated load shedding when your building is riding on UPS and generator power, preserving battery autonomy for the loads that genuinely matter.

GSAŌĆÖs guidance on building energy security and efficiency adds the energy storage perspective. They describe how batteries increase demand flexibility and are central to gridŌĆæinteractive efficient buildings. With storage in place, a facility can participate in utility demand response programs, take advantage of timeŌĆæofŌĆæuse tariffs, limit demand charges, and improve utilization of onŌĆæsite generation such as solar photovoltaics. Crucially, GSA also points out that stored energy can act as a backup power source during outages, enhancing resilience.

In a typical commercial power architecture, that storage function is delivered by a combination of buildingŌĆæscale batteries and smaller UPS systems feeding critical IT and control loads through inverters. When building automation is aware of the state of those systems, it can automatically reduce or shed flexible loads as battery state of charge drops, adjust chilled water or air distribution to coast through short outages, and coordinate with generators and transfer switches to avoid simultaneous peaks when utility supply returns.

Spacewell and Zenatix both emphasize granular energy monitoring at equipment and circuit levels. When you map those points to protected versus unprotected circuits, you gain a clear view of where UPS capacity is being consumed unnecessarily by nonŌĆæcritical loads and where additional protection might be warranted. Over time, trend data from BAS and energy management systems informs whether you should reconfigure panelboards, relocate UPSŌĆæbacked receptacles, or resize UPS modules to match the actual critical load profile rather than nameplate guesses.

National Facilities Direct and Matterport both highlight the stakes for 24/7 facilities such as hospitals and data centers, where downtime can cost thousands of dollars per minute. Integrated automation with robust power monitoring gives you earlier warning of overloads, overheating, or abnormal voltage conditions. Combined with digital twins and remote troubleshooting, these tools let your team model maintenance scenarios and coordinate interventions so that you must rely on UPS and generator power as infrequently and as predictably as possible.

Moving from legacy controls to an integrated, powerŌĆæaware smart building does not require a single, massive project. Most successful programs advance in deliberate stages, but they keep the endŌĆætoŌĆæend picture in mind from day one.

RasMech recommends starting with a clear assessment of existing systems and loads. That means inventorying HVAC, lighting, and electrical equipment; mapping where automation already exists; and identifying highŌĆæconsumption systems and plug loads. GSA suggests using energy audits and energy modeling to compare projected performance to baseline cases and to factor in evolving needs such as electric vehicle charging. This is also the right point to define buildingŌĆælevel objectives around energy savings, uptime, comfort, and compliance.

Neuroject, Zenatix, and Digi all advise beginning implementation on the systems with the largest energy and business impact, typically HVAC and lighting. IoT sensors and smart controllers can be retrofitted zone by zone, feeding a centralized BAS or cloud platform. The key is to adopt open protocols and architectures that will integrate with your existing BMS rather than creating new islands. AlbireoŌĆÖs overview of BAS types reinforces the value of open standards such as BACnet and Modbus and technologyŌĆæagnostic, multiŌĆævendor integration so you avoid vendor lockŌĆæin and keep future options open.

RasMech points out that while about 60% of large U.S. commercial buildings over 50,000 square feet have some form of BAS, only around 13% of small to medium buildings have comparable systems. That means more than threeŌĆæquarters of all commercial buildings represent untapped opportunity. For those smaller sites, Eptura and Digi describe how cloudŌĆæbased, IoTŌĆæcentric approaches with lowŌĆæcost sensors and SaaS maintenance platforms can deliver much of the same value without the complexity of traditional onŌĆæpremises BMS deployments.

As you expand from initial pilots, Spacewell and Tecknoworks both emphasize the importance of integrating BAS data with portfolioŌĆælevel energy management and analytics. Platforms like SpacewellŌĆÖs energy management system or EnerviseŌĆÖs cloud integration tools aggregate multiŌĆæbuilding consumption patterns and equipment performance so you can identify waste not just within a single facility, but across a campus or regional portfolio.

Throughout this roadmap, commissioning and reŌĆæcommissioning are your safety nets. GSAŌĆÖs building commissioning guidance and RasMechŌĆÖs professional installation steps both stress the need to verify that systems are planned, designed, installed, tested, and maintained to meet performance requirements. That process does not end at handover; it should be revisited periodically as occupancy patterns, equipment, and energy tariffs change.

As soon as you connect building automation and power systems to networks, you invite cyber risk. ZPE Systems warns that smart building systems are attractive attack targets because they often run outdated software and may not be governed by the same security policies as IT assets. They recommend applying Zero Trust principles, which assume no implicit trust and require strict access control, identity verification, and network segmentation for every entity on the network.

ZPE also highlights the challenge of keeping operating systems and management software patched across many devices and facilities. They describe centralized platforms, such as their Nodegrid solution, that consolidate patch management and allow operators to view software versions and push updates remotely from a single console. Digi and National Facilities Direct similarly stress that smart buildings must strengthen cybersecurity as they integrate IoT sensors, AI, and remote access, using encryption, authentication, and ongoing security updates.

From a power system standpoint, loss of visibility or control can be as damaging as a physical fault. That is why governance matters as much as technology. DŌĆæTools advises vetting providers for track records, guarantees, and robust postŌĆæinstallation support, while RasMech highlights ongoing maintenance, calibration, and staff training as prerequisites for longŌĆæterm BAS success. In practice, this means your IT security team, facility engineers, and energy managers must share a common view of which systems are critical, which networks they ride on, and how changes are requested, approved, and logged.

Several documented projects illustrate what integrated automation can deliver when it is well designed and linked to energy and power objectives.

Schneider Electric describes the Aspiria campus in the United States, where integrated building technologies delivered a roughly 16% annual reduction in energy use and a 36% reduction in emissions, with payback in about two years. Their Origine mixedŌĆæuse development in France reportedly consumes only around oneŌĆæsixth of the energy of comparable buildings without a modern building management system, showing what is possible with a highly optimized envelope and integrated controls.

National Facilities Direct points to The Edge building in Amsterdam, which uses IoT sensors extensively to optimize lighting and HVAC and achieves an approximate 70% reduction in energy consumption compared with conventional buildings. EpturaŌĆÖs IoT case study of a sensorŌĆæequipped green building achieved the earlier mentioned 20% cut in electricity, 23% reduction in water, and 25% reduction in natural gas over just 60 days, driven by realŌĆætime adjustments rather than static design measures.

Matterport shares industrial examples where combined IoT and digital twins generated about 25% lower operational costs and 15 to 30% lower energy use for INVISTA by supporting automated monitoring and optimized workflows. RasMechŌĆÖs summary of the U.S. Department of Energy study, with 29% average energy savings from BAS across commercial buildings, reinforces that these results are not limited to flagship smart buildings; they are achievable across mainstream building stock when controls are used effectively.

A simple calculation shows the stakes. If a large commercial campus consumes 10,000,000 kilowattŌĆæhours per year, a 29% reduction of the kind cited in the DOE study would save 2,900,000 kilowattŌĆæhours annually. Depending on local tariffs and demand charges, that often translates into hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, before even accounting for the improved reliability and resilience that come from lower and more predictable loads on your power systems.

Here is a concise comparison of several documented outcomes.

| Project or Study | Approach | Reported Result | Source or Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOE BAS study (commercial buildings) | BAS with improved HVAC control | About 29% average energy savings, over 40% in some uses | RasMech summarizing DOE |

| Aspiria campus | Integrated BMS and building technologies | Around 16% energy and 36% emissions reduction, twoŌĆæyear payback | Schneider Electric |

| Origine mixedŌĆæuse site | Advanced BMS and smart building design | About oneŌĆæsixth of comparable buildingsŌĆÖ energy use | Schneider Electric |

| IoTŌĆæenabled green building (60ŌĆæday study) | IoT sensors and realŌĆætime operational adjustments | 20% less electricity, 23% less water, 25% less gas | Eptura |

| The Edge building | Dense IoT and smart controls | Approximate 70% lower energy use than conventional | National Facilities Direct |

| INVISTA industrial operations | IoT and digital twins for monitoring and workflows | Around 25% lower operational costs, 15ŌĆō30% lower energy | Matterport |

The benefits of integrated automation, especially when tied to power and reliability, are substantial and wellŌĆædocumented across the sources above. Energy savings, lower operating costs, better comfort, improved indoor air quality, and higher uptime all recur. BAS and IoT platforms create a data foundation that supports predictive maintenance, demand response, participation in flexible tariffs, and progress toward certifications such as LEED and WELL, as discussed by Spacewell and Digi.

At the same time, Albireo, GSA, DŌĆæTools, and RasMech all point to real challenges. Upfront costs for hardware, software, design, and installation can be significant, especially in older or complex buildings. Integration with legacy systems is nonŌĆætrivial and may require gateways, protocol translation, and careful commissioning. Albireo notes that userŌĆæfriendly interfaces and training are essential; otherwise, facility staff can be overwhelmed, and systems revert to manual overrides that undermine efficiency.

DŌĆæTools warns that poorly configured or malfunctioning BAS can actually increase energy use, as in the Rush University example. ZPE Systems and National Facilities Direct underscore that smarter buildings expand the cyber attack surface, demanding Zero TrustŌĆæstyle security, segmentation, patching, and careful vendor management. GSA reminds us that energy upgrades must avoid unintended consequences for comfort or health, especially when envelope, ventilation, and HVAC changes interact.

For power system specialists, an additional nuance is that more automation means more dependency on reliable control networks and software. That makes resilience planning, including segregation of critical protection and transfer functions from higherŌĆælevel optimization, all the more important. Done thoughtfully, automation becomes a powerful ally rather than a brittle dependency.

Not necessarily. CIS Industries, Neuroject, Eptura, and Digi all show that you can begin with targeted IoT and control upgrades on the biggest loads, typically HVAC and lighting, and layer them onto existing systems. The key is to choose open, integrable technologies so those first steps can plug into a broader BAS or building management platform later. For smaller buildings that lack a legacy BMS, cloudŌĆæbased solutions with wireless sensors can provide meaningful benefits without a full traditional BAS deployment.

Schneider Electric and GSA both emphasize that when power management, energy storage, and building controls share data, you can prioritize loads and coordinate behavior during grid events. In practical terms, integrating meters, panel monitors, and UPS or battery status into the automation platform lets you shed nonŌĆæcritical loads early, reduce simultaneous peaks during transfer events, and make the most of battery capacity and generator runtime. The building automation system does not replace protective relays or transfer switches, but it can orchestrate how controllable loads respond around those core power protection devices.

Payback varies widely with building type, baseline efficiency, local energy costs, and the depth of automation. Schneider Electric reports a roughly twoŌĆæyear payback for the Aspiria campus, while RasMech cites a U.S. Department of Energy study showing average energy savings of 29% from BAS across commercial buildings. EpturaŌĆÖs and MatterportŌĆÖs case studies demonstrate that wellŌĆætargeted IoT and analytics projects can deliver doubleŌĆædigit percentage reductions in energy and operational costs. In my experience, projects that start with highŌĆæconsumption systems, use open standards, and are paired with disciplined commissioning are most likely to achieve attractive payback times.

As you plan your next round of upgrades, treat building automation as part of your power and reliability strategy, not just an energy project. When the BAS, meters, UPS, inverters, and generators all speak the same language, you gain control over when and how your building uses energyŌĆöand that control is the foundation of both resilient operations and sustainable performance.

Leave Your Comment