-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for ŌĆ£ŌĆØ.

Modern precision machining centers live or die on the stability and intelligence of their CNC systems. The cutting spindle, axes, and tooling get the attention, but in practice the control, software, maintenance discipline, and electrical health determine whether a metalŌĆæcutting center quietly holds tenths of a thousandth of an inch all week or spends that week in alarm states and downtime.

This article looks at CNC systems for precision metal cutting from the standpoint of reliability and uptime. Drawing on guidance and case studies from sources such as YCM Alliance, FANUC training programs, Baker Industries, MachineMetrics, and several CNC maintenance and machining specialists, it explains how to specify, operate, and maintain CNC machining centers so they cut accurately and predictably day after day.

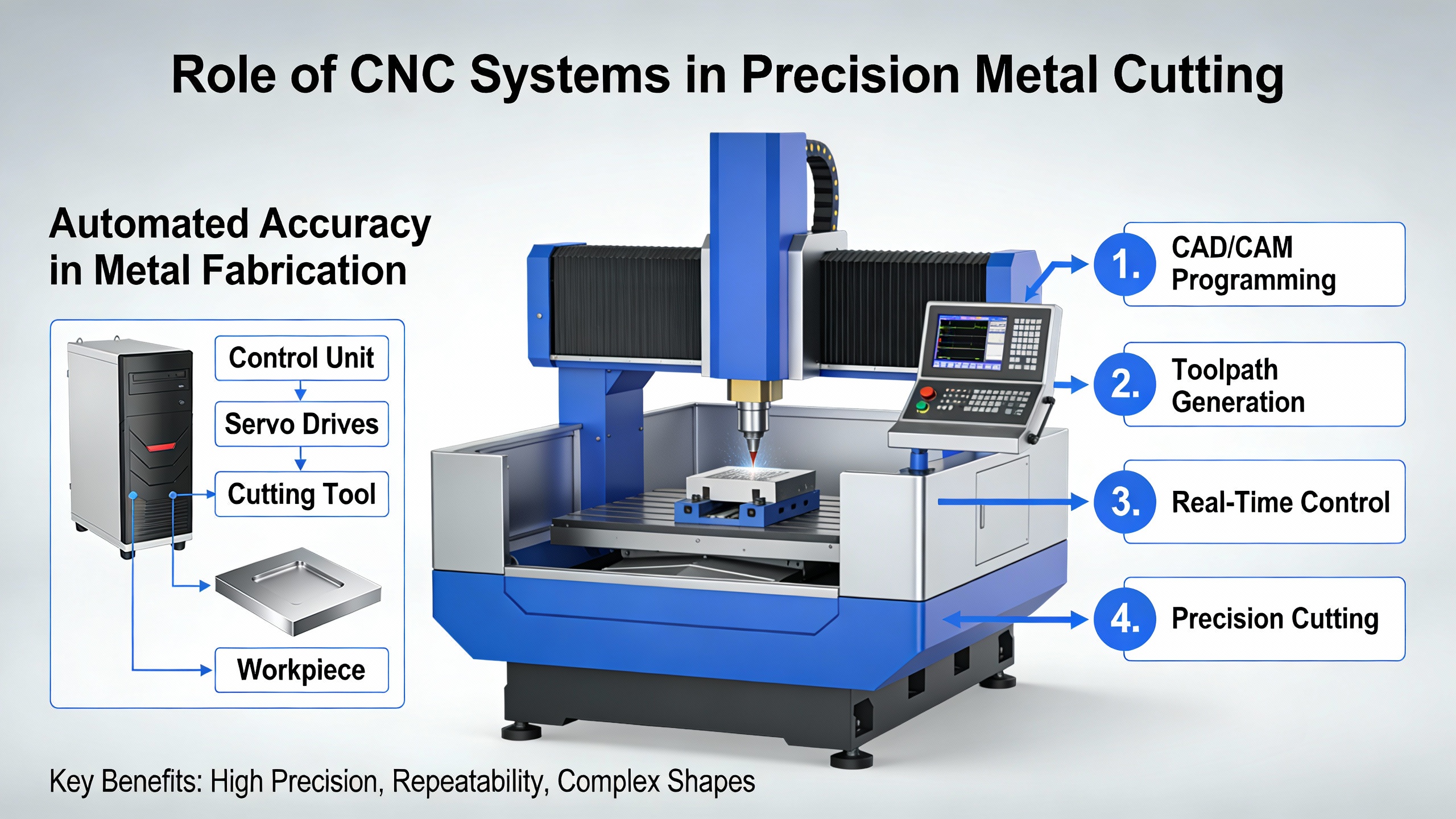

Computer numerical control (CNC) machining is a subtractive process where a digital model becomes a part through controlled cutting. As described by YCM Alliance, the typical flow starts with CAD design, moves into CAM toolpath generation and simulation, then into machine setup, automated execution, and final quality control. GŌĆæcode drives the machineŌĆÖs motion system so the cutting tool follows exactly the path the programmer intended.

Compared with manual machines, CNC machining delivers far higher repeatability and far tighter tolerances. Modern systems routinely hold positional tolerances on the order of plus or minus 0.0001 inches, supported by rigid frames, highŌĆæspeed spindles, and precision motion systems. CNC turning centers can finish cylindrical parts with surface roughness on the order of 0.2 to 0.8 micrometers Ra, which is roughly 8 to 31 microinch Ra. That level of consistency is why CNC machining dominates in aerospace, medical devices, automotive powertrain components, and other highŌĆæspec metal parts, as noted by YCM Alliance and Goodwin University.

Goodwin University also points out that CNC machining is a growth field: the global CNC machine market is projected to expand significantly, driven by demand for automation, precision, and efficiency. That growth is not just about buying more iron. It is about deploying CNC systems that combine accurate machines, capable software, trained people, and disciplined power and maintenance practices.

For metal cutting, CNC systems excel when part geometry is compatible with subtractive machining. Protolabs Network notes that relatively simple metal geometries that can be milled or turned without elaborate fixturing are generally better suited to CNC machining than to 3D printing. CNC offers better dimensional accuracy and mechanical properties than additive processes, at the cost of more stringent design constraints and higher unit cost at very low volumes.

Those advantages only matter if the machining center is reliably available. FANUC training material documents an automotive manufacturer that reduced CNC downtime by about 30 percent and increased output by 20 percent in six months by improving training, setup, and maintenance. Another case from MachineMetrics describes a shop that recovered roughly 6,900 hours of machine capacity and doubled utilization primarily through better setup tracking and process discipline, not by replacing machines.

A simple example illustrates the leverage: imagine a precision machining center scheduled for 60 hours of production per week but losing 6 hours to avoidable setup issues and small stoppages. That is a 10 percent hit to capacity. If process improvements and training similar to those described by FANUC and MachineMetrics cut that loss in half, the shop gains 3 hours of extra spindle time per week on the same installed base. Over 50 working weeks, that is 150 additional production hours without buying a single new machine.

From a reliability perspective, the CNC control is not just about trajectory generation. It is a system of mechanics, electronics, software, power, and people that either protects or squanders those hours.

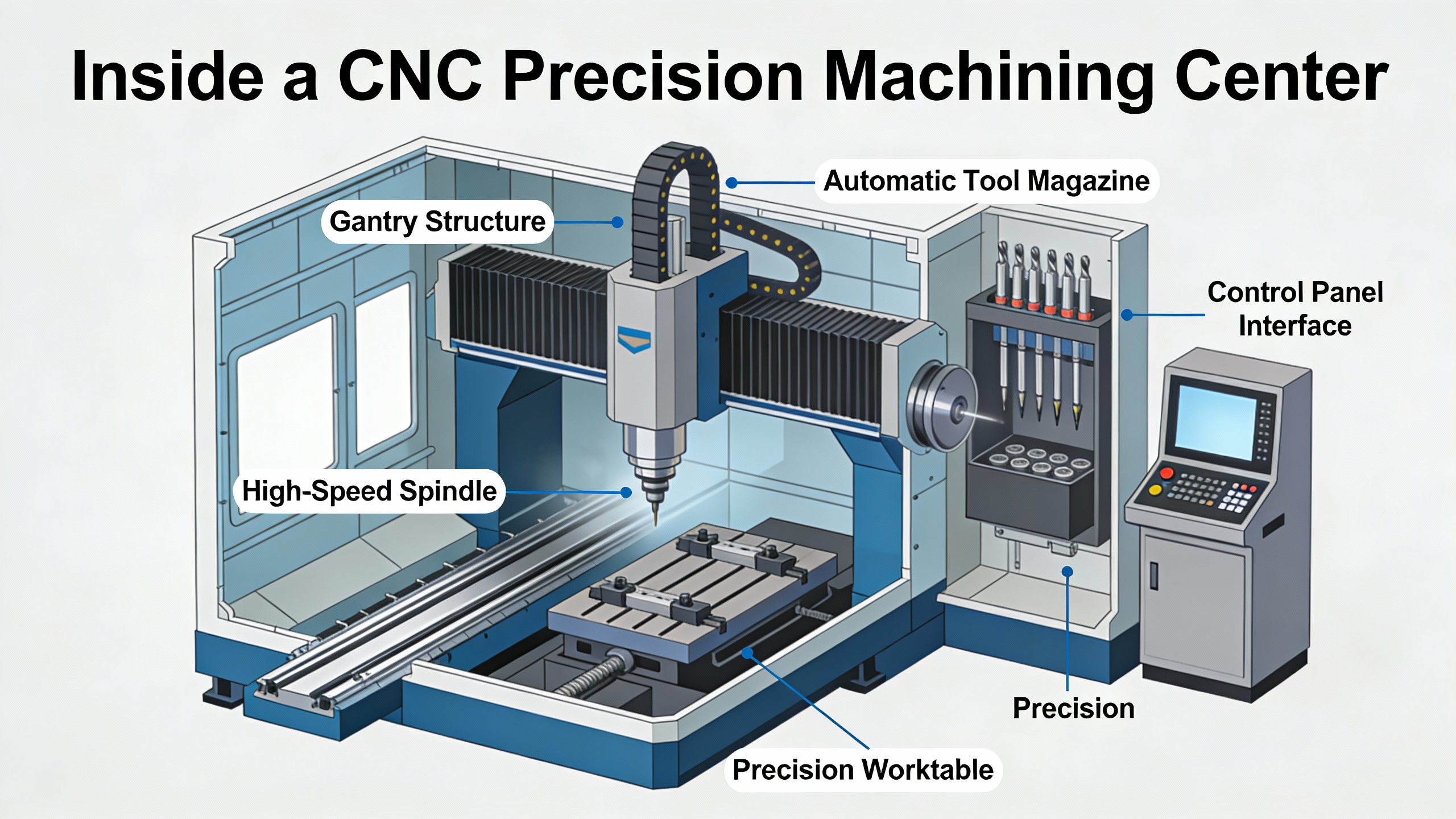

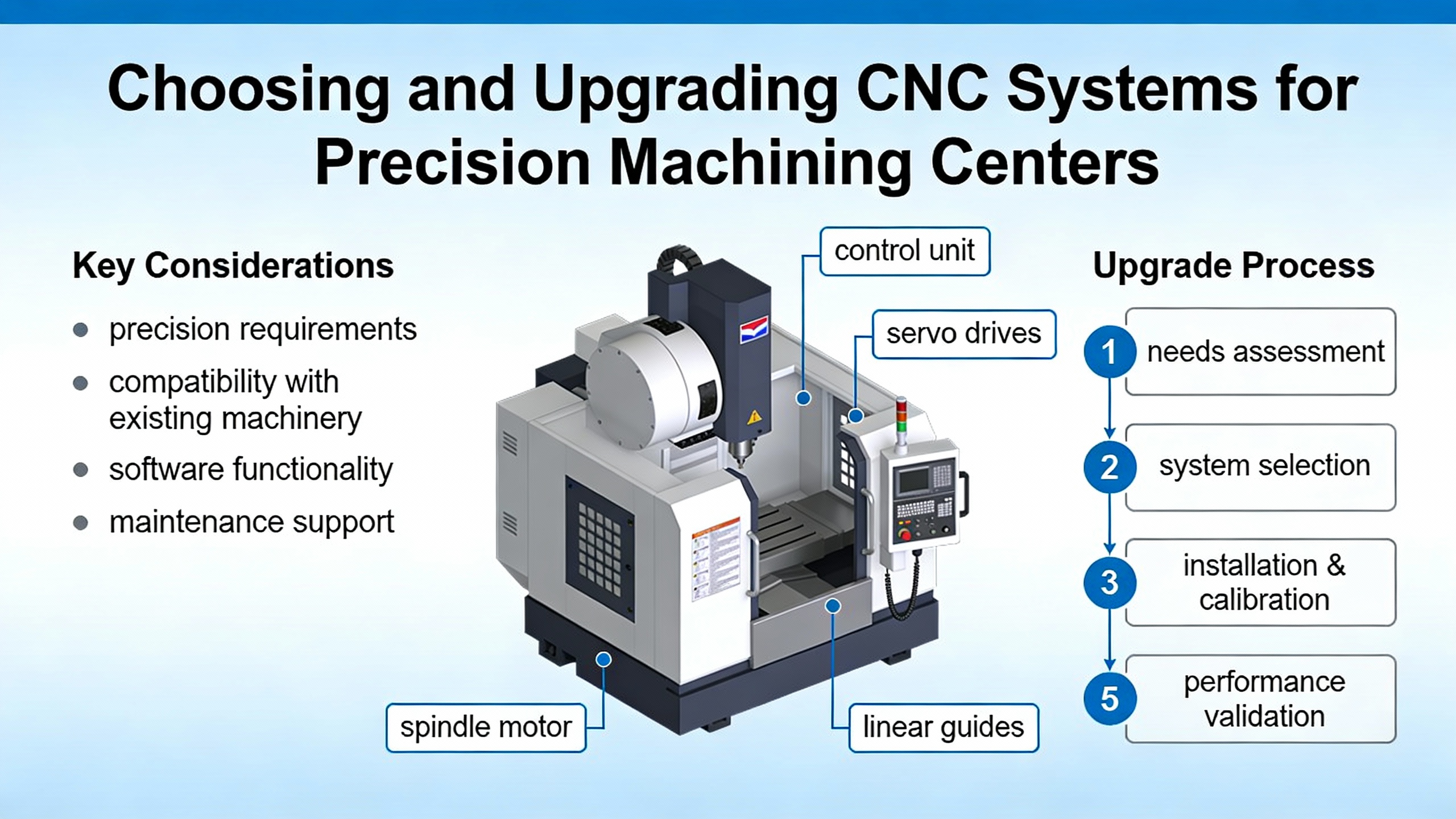

A precision machining center is more than a spindle and table. YCM Alliance describes several core elements that must work together:

The machine frame, usually cast iron or steel, provides rigidity and vibration damping. Any flex or instability here shows up as poor surface finish or drift in dimensions.

The spindle system brings power and speed to the cutting tool. MetalŌĆæcutting machining centers often run at tens of thousands of revolutions per minute, making lubrication, balancing, and cooling critical.

Linear motion systems, usually ball screws or linear motors, drive each axis. In a vertical or horizontal machining center you might see three to five controlled axes; in a turning center you typically see X and Z, with optional C and Y or B for live tooling and offŌĆæcenter features.

The CNC control interprets GŌĆæcode, coordinates all axis motion, and manages subsystems such as tool changers, coolant delivery, probing, and safety interlocks.

On the turning side, specialists such as CNC turning machine manufacturers describe the spindle and chuck holding the rotating workpiece, a tool turret indexing multiple inserts, and a tailstock or subŌĆæspindle supporting long parts or enabling backŌĆæside operations. Coolant and chip systems protect surface quality and tool life by evacuating chips and removing heat.

Every one of these subsystems depends on stable power, clean electrical cabinets, accurate feedback devices, and a control system free of latent faults. Maintenance guides such as those from CNC.works emphasize inspecting electrical connections, monitoring power supply stability, and keeping cabinets sealed and dustŌĆæfree to protect these elements.

CNC machining centers handle several fundamental metalŌĆæcutting operations. YCM Alliance and other sources identify milling, turning, drilling, boring, and grinding as the most common.

Milling centers remove material with rotating tools against a stationary workpiece. They excel at pockets, slots, contoured surfaces, and precision planar faces. ThreeŌĆæaxis mills handle most prismatic work, while fiveŌĆæaxis machines or threeŌĆæaxis machines on tilting tables allow access to multiple faces in a single setup, a point reinforced by both CNC Yangsen and ScarlettŌĆÖs efficiency guidance.

Turning centers spin the workpiece instead. According to CNC turning bestŌĆæpractice guidance, basic lathes use two axes for facing and turning diameters, while more advanced turning centers add CŌĆæaxis, live tooling, and often Y or B to mill flats, drill crossŌĆæholes, and cut complex offŌĆæcenter features in one setup. Fine finishing on such turning centers can produce the microinchŌĆælevel surfaces mentioned earlier, making them ideal for shafts, bushings, and medical implants that must mate or move smoothly.

Research into reconfigurable machining centers, such as the HTM50200 specialŌĆæshaped stone system, shows how flexible structures can support more diverse geometries. That machine uses a rotatable cross beam to switch between horizontal and vertical configurations while maintaining good dynamic behavior. Although the study focuses on stone, it highlights a broader point: mechanical layouts that can be reconfigured or that offer more accessible axes can help a machining center adapt to varied part families without sacrificing stability.

Realistically, your precision metalŌĆæcutting center may not have a spinning cross beam, but the same principle applies when you consider whether to invest in trunnion tables, additional rotary axes, or subŌĆæspindles. The objective is always the same: reduce setups while protecting stiffness and dynamic performance.

Even the best machining center cannot overcome a poor process plan. JLCCNCŌĆÖs process tips highlight that you should group operations thoughtfully, usually in three intertwined ways.

One approach is to group by tool so each tool completes all its possible features before a change. That reduces toolŌĆæchange time and positioning errors. A second is to group by part features, often tackling flat surfaces, datum features, and lowŌĆæprecision areas before complex contours and tightŌĆætolerance zones. A third is to separate roughing from finishing, especially for thinŌĆæwalled or easily deformed components, so finishing cuts see a stable, predictable geometry.

They also emphasize preserving rigidity and datum integrity in the sequence. Internal cavities are generally machined before external features so that the remaining stock keeps the part stiff during aggressive roughing. Operations using the same clamping and locating strategy should be chained together to minimize reclamping and workpiece movement, which directly affect precision.

Good clamping and reference strategies complete the picture. process experts recommend unifying design datums, process datums, and programming zero points where possible, minimizing the number of clamps, and avoiding manual adjustments that depend on operator judgment. Carefully chosen workpiece coordinate systems tied to reliable reference surfaces give the control a stable coordinate frame, which is crucial for holding tight tolerances across long runs.

Machining Concepts in Erie, Pennsylvania frames toolpaths as one of the central levers for CNC efficiency. Toolpaths are the programmed routes the cutting tool follows. The goal is to remove metal as efficiently as possible while protecting dimensional accuracy, surface finish, and tool life.

Several basic toolpath patterns show up repeatedly in precise metal cutting:

Contour or profile toolpaths follow part edges or final surfaces. They are used to finish walls or external shapes where accuracy and finish matter.

Pocketing toolpaths clear interior areas, often with zigŌĆæzag or trochoidal moves designed to maintain consistent cutter engagement.

Drilling paths position the tool and execute various cycles, including peck drilling to manage chips in deep holes.

Facing toolpaths flatten surfaces with parallel or zigŌĆæzag passes, establishing reference planes for downstream work.

More advanced strategies include 3D contouring for sculpted surfaces, spiral or radial paths for deep cavities or round features, and adaptive or highŌĆæefficiency milling that keeps chip load and engagement angle nearly constant. These adaptive methods allow higher cutting speeds and deeper stepŌĆædowns in hard metals while limiting tool vibration and heat.

A concise way to compare key toolpaths is shown below.

| Toolpath type | Typical metalŌĆæcutting use | Primary benefit for precision centers |

|---|---|---|

| Contour/profile | Finishing walls, external shapes | High dimensional accuracy and surface finish |

| Pocketing | Clearing cavities and pockets | Efficient material removal with controllable loads |

| Drilling/peck drilling | Holes and deep bores | Chip control and reduced risk of drill breakage |

| Facing | Creating flat datum surfaces | Stable reference planes for later operations |

| Adaptive / spiral | Deep pockets, hard alloys | Consistent tool engagement and better tool life |

CAD/CAM software sits at the center of this strategy. Both Machining Concepts and YCM Alliance underline the importance of using CAM to generate and simulate toolpaths before cutting. Simulation can catch collisions, overŌĆætravels, and tool deflection risks in software instead of in the machine. It also lets programmers test feed rates, stepŌĆæovers, and depth of cut to find a balance between shorter cycles and acceptable tool wear.

ScarlettŌĆÖs CNC efficiency guidance adds that skilled programmers should favor robust, comprehensive programs and subroutines over fragmented code. Excessive manual edits or small incremental changes increase the risk of accumulated positioning errors over many runs. Treating the CNC program as a stable, versionŌĆæcontrolled asset supports both accuracy and reliability.

Machining Concepts emphasizes that seconds taken out of a CNC cycle translate directly into cost savings and higher throughput. A short example shows why.

Assume a machining center runs a critical metal part in batches of 2,000 per year. If optimized toolpaths, reduced rapids, and fewer tool changes trim only 5 seconds from the cycle, that is 10,000 seconds saved annually. Dividing by 3,600 seconds per hour, the shop gains about 2.8 hours of spindle time each year on that part alone.

At first glance that may sound minor. But if a shop can remove a similar five seconds from ten different highŌĆævolume parts, that is nearly 28 hours of extra machine time. Combined with setup time reductions and less downtime from errors, the gains add up quickly. MachineMetricsŌĆÖ case study with General Grind and Machine showed that removing unnecessary setup time across 126 setups in a month recovered 74 hours of capacity and ultimately contributed to about 6,900 hours of additional machine availability.

In a precision machining center where capital costs are high, this reclaimed time can postpone or eliminate the need for another machine while keeping delivery commitments intact.

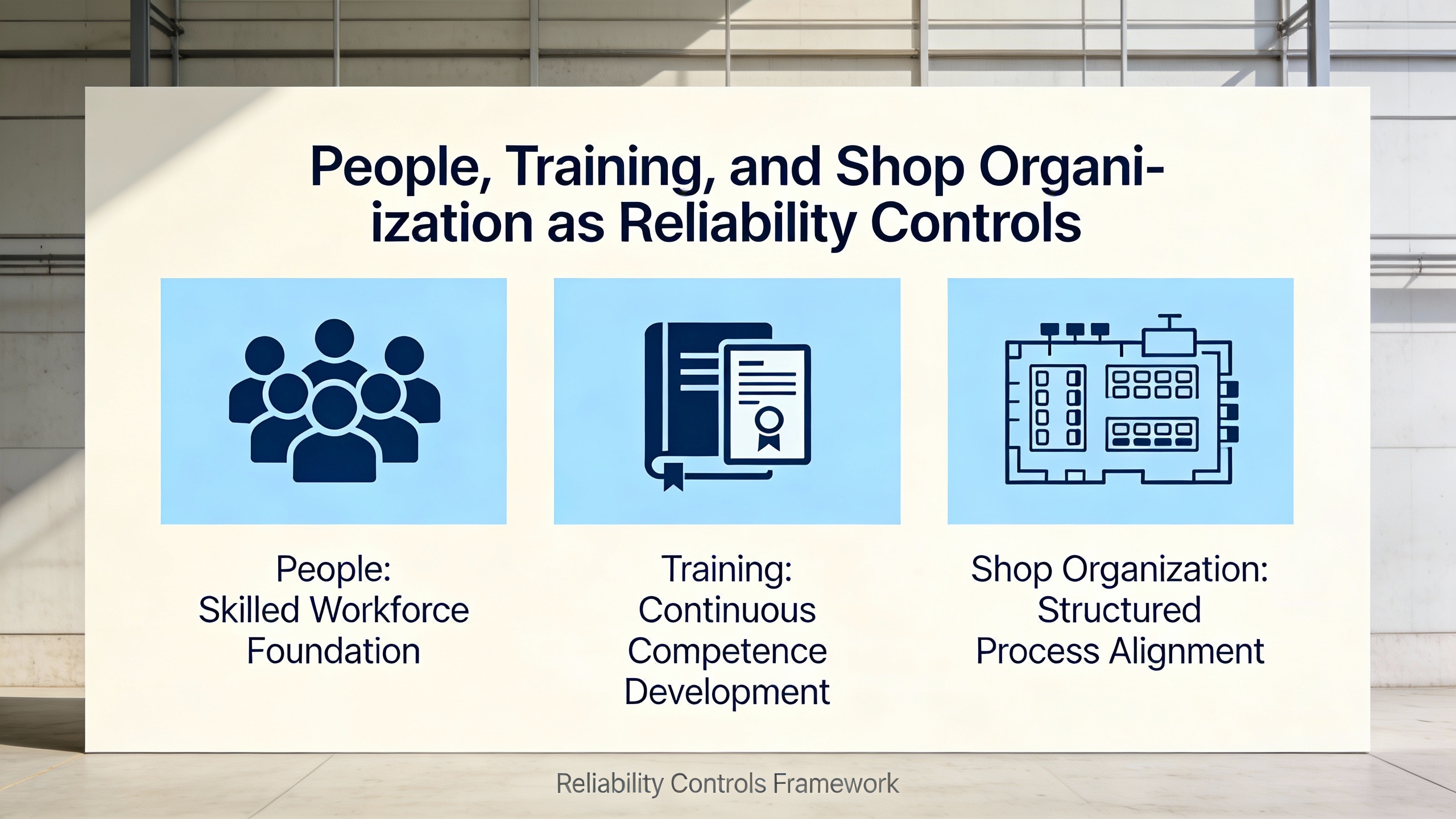

Multiple sources stress that CNC performance is limited less by hardware and more by how people set up, program, and maintain it. FANUC and T.I.E. Industrial define CNC training as structured education in setup, programming, troubleshooting, and preventive maintenance. Without that training, operators commonly misŌĆæset tools, misuse cutting parameters, or overlook early signs of problems, driving scrap and unplanned downtime.

FANUC reports several case studies that quantify the impact. An automotive manufacturer implementing comprehensive CNC training reduced downtime by about 30 percent and increased output by 20 percent within six months. An aerospace company that invested in handsŌĆæon multiŌĆæaxis training cut setup time by around 25 percent, improved material utilization, and reduced scrap. A small job shop that trained operators in proper tool selection and routine maintenance gained roughly 15 percent more uptime and 10 percent higher productivity. A heavy equipment manufacturer saw unplanned downtime fall by 35 percent and overall equipment effectiveness rise by 22 percent after training operators to detect early wear and calibrate machines correctly.

Education bodies such as Goodwin University underline that CNC machining remains a handsŌĆæon, highŌĆæskill profession despite the automation. Their data shows widespread difficulty in filling skilled machining roles and notes that machinists with strong training can expect solid earning potential. From a reliability standpoint, those trained professionals are the first line of defense against misŌĆæset offsets, poor tool choices, and overlooked maintenance tasks.

The layout and management of the machining center environment matter almost as much as the machine specification itself. ISAŌĆÖs guidance on CNC shop efficiency advocates treating the shop floor holistically: machines, tools, people, and physical layout should all be organized around a smooth workflow. Machines and workstations should be spaced and arranged to reflect daily work patterns so parts and tools flow naturally rather than crissŌĆæcrossing the floor.

Organized tool and material handling is a recurring theme. Both ISA and Scarlett recommend standardized storage with clear labeling, fixed locations, and highŌĆæquality tool cabinets or shadow boards. Grouping frequently used tools near each machine reduces walking and search time and supports safer, cleaner workspaces. Clear roles and simple hierarchies on the floor help everyone understand who owns setup, who verifies programs, and who is responsible for maintenance checks.

MachineMetrics frames CNC setup as a controllable form of downtime. They define setup time as the interval between the last good part of one job and the first good part of the next. Their recommendations include structured preŌĆæchecks for coolant and chips, standardized tool loading and inspection, consistent machine calibration steps, and initial slow runs with careful quality checks. They also suggest measuring setup time carefully, then staging tools and materials in kits or carts, grouping part families to reduce reconfiguration, and documenting best practices from the fastest, most reliable setups.

Their General Grind & Machine example is instructive. Over one month, 126 setups across 20 machines consumed about 212 hours of nonŌĆæproduction time, with each setup averaging 35 minutes more than the standard. By instrumenting setups, reviewing data weekly, and even creating a specialized ŌĆ£pit crewŌĆØ setup team, the shop unlocked roughly 6,900 hours of capacity and doubled machine utilization.

A simple scenario illustrates the leverage for a precision machining center. If a shop runs ten setups per day and can remove just 10 minutes from each, that is about 100 minutes, or 1.7 hours, of extra machine availability per day. Over a fiveŌĆæday week, that adds up to more than 8 hours, effectively one full extra shift of cutting time without touching the power or mechanical ratings of the machines.

In practice, that efficiency depends on alignment between human factors, programming discipline, and maintenance. From a reliability advisorŌĆÖs viewpoint, training operators to treat setup and organization as part of the protection system for the machine is one of the most costŌĆæeffective investments a shop can make.

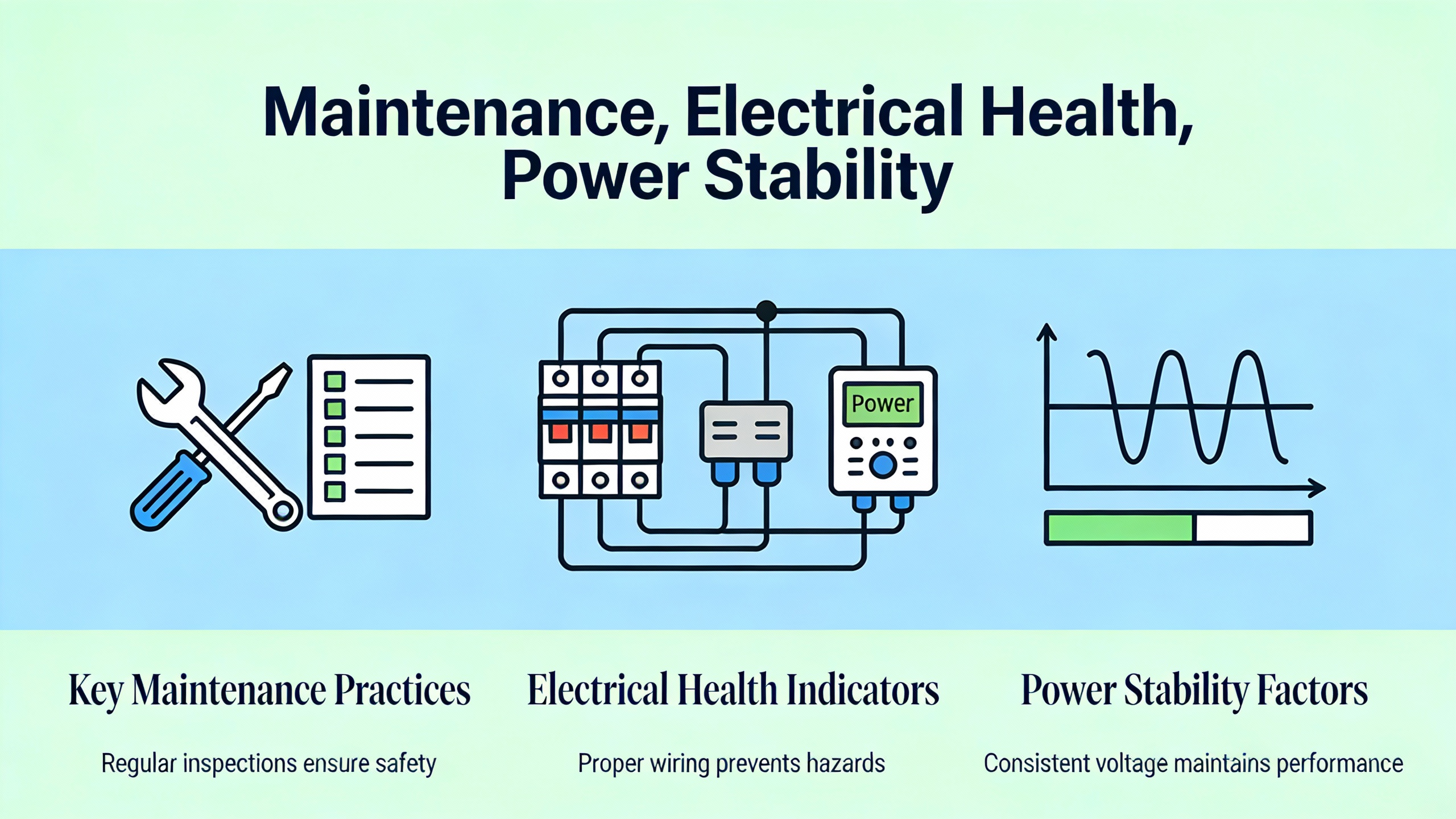

CNC machining centers are capital assets that must stay within tight mechanical and thermal tolerances to hold micronŌĆælevel positioning. A broad set of maintenance sources, including CNC.works, LMW, MROElectric, MachineMetrics, SW Machine Tech, and CNC Masters, all converge on the same theme: maintenance must be structured, frequent, and increasingly dataŌĆædriven.

Most guides recommend daily, weekly, monthly, and annual tasks. Daily actions focus on cleanliness and safety: removing chips and dust, wiping down surfaces, checking coolant and lubrication levels, and verifying that emergency stops and indicator lights work. Weekly and monthly tasks dig deeper into lubrication points, filter condition, spindle and axis health, and the condition of chucks and workholding. Annual tasks include draining and cleaning coolant tanks, replacing all lubricants, and performing deeper inspections or overhauls, particularly of spindles and ball screws.

SW Machine Tech emphasizes aligning maintenance windows with production schedules so that preventive work happens during offŌĆæpeak times, minimizing impact on deliveries. They also encourage moving from strict calendarŌĆæbased preventive maintenance toward conditionŌĆæbased maintenance that monitors usage patterns and machine condition in real time, then triggers maintenance only when needed.

MachineMetricsŌĆÖ maintenance overview explains how predictive or conditionŌĆæbased strategies use sensors on temperature, vibration, and other indicators to detect when components are nearing failure. Wireless monitoring and dashboards can send this data to techniciansŌĆÖ smartphones or tablets, allowing them to schedule repairs just in time. Their experience suggests that predictive approaches often reduce unnecessary maintenance, lower unplanned downtime, and improve profitability, especially for critical machining centers.

Across these sources, a consistent message emerges: an effective program combines routine checklists, conditionŌĆæbased monitoring, clear reporting channels, and accurate maintenance records. CNC Masters and LMW both highlight the importance of keeping a log of inspections, parts replacements, and faults to spot recurring issues and support more accurate diagnosis.

CNC machining centers are electrically complex, with drives, encoders, control boards, and safety circuits all vulnerable to poor power quality or contamination. CNC.works devotes specific attention to electrical maintenance. Their guidance includes inspecting wiring and connections regularly for looseness caused by vibration, keeping electrical cabinets sealed and free of dust, checking fuses and breakers, and monitoring power supply voltage stability.

Stable voltage and clean power are essential for avoiding spurious faults and protecting sensitive electronics. While the articles do not prescribe specific mitigation hardware, they agree that monitoring is essential and that any irregularities should be addressed promptly by qualified electrical or facility specialists. Keeping cabinets closed and clean, maintaining filters, and ensuring that cooling systems are working properly all contribute to thermal and electrical stability inside the cabinet.

CNC Yangsen adds that environmental control of the workshop itself matters. Stable temperatures, clean compressed air, and appropriate placement of compressors and other heat sources reduce thermal drift and contamination, both of which can affect CNC accuracy and reliability.

From a reliability advisory perspective, these recommendations mean that power quality and environmental monitoring should be treated as part of the CNC system. Operators and maintenance staff should be trained to notice flickering lights on drives, repeated nuisance alarms, or unusual cabinet temperatures and to route these issues through a clear reporting channel, as CNC Masters and MachineMetrics advise.

It is useful to visualize the impact of neglected maintenance with a simple hypothetical. Suppose a machining center runs two shifts per day, five days per week, totaling roughly 80 scheduled hours. If coolant concentration is not checked and adjusted as part of the daily tasks, as recommended by several maintenance guides, tool life may shorten and spindle temperatures may rise unnoticed. Over weeks, that extra heat and stress can accelerate spindle bearing wear.

If the spindle eventually fails, the machine could be down for a full workweek or longer while parts are sourced and repairs completed. If that failure removes 40 hours of cutting time in a week, then a habit of skipping ten minutes of daily checks saves at most about 50 minutes per week but risks losing 40 hours in a single event. Although the exact numbers will vary, qualitative guidance from LMW, CNC.works, and MROElectric all point to the same conclusion: modest, consistent care pays back many times over by avoiding large breakdowns.

ConditionŌĆæbased monitoring further sharpens this tradeŌĆæoff. If vibration sensors and temperature logs show that a spindle is trending toward an issue, maintenance can be scheduled during a planned stoppage and parts can be ordered in advance. That is the maintenance equivalent of a wellŌĆædesigned power protection system: problems are identified early and handled on your terms, not in the middle of a critical production run.

Baker Industries describes CNC quality control as a preventive, dataŌĆædriven discipline. Instead of measuring a few parts and hoping the process stays centered, they recommend statistical process control (SPC) and quality software.

SPC involves collecting dimensional data during production and plotting it on control charts to detect trends before parts go out of tolerance. When variation starts to creep toward the limits, the team can investigate and adjust offsets, feeds, or tooling while good parts are still being made. This reduces scrap, rework, and schedule disruptions.

Quality control software amplifies these practices by providing realŌĆætime dashboards of machine performance and quality metrics, automating some inspection steps, and maintaining traceable records of which batches met which specifications. Enhanced traceability supports customer audits and reduces the cost of quality by making it easier to pinpoint where and when a drift occurred.

MachineMetrics echoes this perspective from the machining side, noting that inŌĆæprocess monitoring and feedback can help operators spot issues with setups or tool wear quickly. When quality and machine data live together, it becomes easier to separate issues caused by programming, setup, or machine health and to respond appropriately.

Baker Industries also emphasizes calibration of measuring tools and machine systems. Accurate gauges and probes are essential to trust the data driving SPC. Their recommendations include using approved reference standards, following a regular calibration schedule, and documenting all results and adjustments.

CNC maintenance sources add that machine calibration is part of the maintenance routine. SW Machine Tech includes regular calibration and early attention to identified issues in their scheduled maintenance programs. CNC.works and LMW suggest using checklists for machine geometry, backlash, and repetition accuracy as part of deeper periodic inspections.

A simple example shows how SPC and calibration interact. Imagine a machining center producing a precision shaft that must maintain a diameter within plus or minus 0.0005 inches. If operators measure a sample of shafts every hour and record the values, a control chart might show a slow drift of a few tenŌĆæthousandths in one direction. If gauges and machines are calibrated and trusted, the team can adjust tool offsets or investigate causes such as tool wear or thermal growth before any shafts exceed the tolerance. If those instruments are not calibrated, the data may be misleading, leading either to unnecessary adjustments or to unnoticed drift until parts fail inspection.

For precision machining centers, investing in measurement and calibration discipline is as important as investing in the CNC hardware itself. From a reliability point of view, quality control reduces the risk that an undetected process change will silently degrade output until an entire batch must be scrapped or reworked.

When specifying or upgrading a machining center, YCM Alliance suggests considering not only cutting capacity but also the mix of operations and the required precision. Milling, turning, drilling, and grinding each have strengths. Turning excels at cylindrical components that benefit from rotating work and stationary tools, while milling handles prismatic parts and complex 3D shapes. Grinding adds ultraŌĆæfine surface finishing when microinchŌĆælevel finishes are required after milling or turning.

CNC YangsenŌĆÖs setup guidance reminds decisionŌĆæmakers to account for machine type as well: mills, lathes, routers, plasma cutters, and EDM machines each target different materials and geometries. For metalŌĆæcutting centers, the common choice is between threeŌĆæaxis machining centers, turning centers, and more complex fiveŌĆæaxis or multitasking machines.

Scarlett and CNC Yangsen both note that upgrading from threeŌĆæaxis to full fiveŌĆæaxis capability, or adding a tilting twoŌĆæaxis table to achieve threeŌĆæplusŌĆætwo positioning, can significantly reduce the number of setups needed for multiŌĆæsided parts. Fewer setups generally mean better accuracy and lower risk of human error, particularly on complex aerospace and medical components. The tradeŌĆæoff is higher machine cost and often more demanding programming and fixturing.

Complementing those decisions is the choice between CNC machining and alternative processes. Protolabs NetworkŌĆÖs comparison between CNC and 3D printing suggests that CNC remains the best choice for most precision metal parts with machinable geometries, offering superior mechanical properties and dimensional accuracy. Additive methods are more attractive for lowŌĆæcost plastic prototypes, very complex geometries that would be hard or impossible to machine, or specialty materials where subtractive processing is inefficient.

The key is to align machine capability with part requirements and production volume. OverŌĆæspecifying machines that spend their lives underutilized is as problematic as underŌĆæspecifying machines that can never meet tolerance or throughput requirements.

Several sources caution that buying a more expensive machining center is not always the fastest path to better results. Scarlett notes that CNC efficiency is often constrained more by operator skill, programming quality, and operational discipline than by machine design. ISAŌĆÖs efficiency tips likewise show that thoughtful floor management, clear roles, and collaborative planning yield large gains. FANUC and Goodwin both emphasize training as the bedrock of improved uptime and quality.

MaintenanceŌĆæoriented sources, including SW Machine Tech, CNC.works, LMW, MROElectric, and MachineMetrics, show that a structured maintenance program with conditionŌĆæbased elements can dramatically reduce unplanned downtime. CNC Yangsen and CNC.works also highlight the importance of environmental control, correct lubrication, and stable power supply for maintaining accuracy.

Supplier choice can help too. YCM Alliance positions itself as a specialized dealer that provides both machines and application engineering support. T.I.E. Industrial not only supplies CNC systems and parts but also offers training. Distributors like Diversified Equipment and Supply, mentioned by CNC.works, can assist with maintenance planning and decisions about repair versus replacement.

A practical way to think about investment is to compare potential gains. FANUCŌĆÖs case studies show uptime and productivity improvements in the 15 to 35 percent range from training alone. MachineMetrics reports one shop doubling machine utilization mainly through better setup practices. By contrast, a new machining center might add capacity but will not automatically solve training gaps, maintenance weaknesses, or process instability.

If a precision machining center currently uses its equipment only half of the available hours due to setups, downtime, and quality issues, improving utilization even to 70 percent yields a significant effective capacity increase. Only after those foundational levers are addressed does it make sense to ask whether additional or higherŌĆæspec machines are needed.

From a reliability and powerŌĆæsystem viewpoint, that sequence is appealing. It directs capital first into reducing avoidable failures and inefficiencies, then into increasing connected load and power requirements only when there is a clear, demonstrable need.

Case studies from FANUC and MachineMetrics, along with multiple maintenance guides, point to humanŌĆædriven issues as the largest source of avoidable downtime. Incorrect setups, poor tool selection, skipped maintenance, and inefficient setups all feature prominently. When shops invest in structured training, clear setup procedures, and disciplined daily and weekly checks, they routinely report doubleŌĆædigit reductions in downtime and significant gains in output.

FiveŌĆæaxis capability improves access to complex geometries and reduces the number of setups, which indirectly supports precision by reducing opportunities for fixturing error. Scarlett and CNC Yangsen both highlight these benefits. However, precision also depends on machine rigidity, control quality, process planning, and operator skill. A poorly planned operation on a fiveŌĆæaxis machine can still produce poor results, while a wellŌĆæplanned process on a threeŌĆæaxis machine can hold tight tolerances for suitable geometries. The decision should therefore be based on part families and process needs, not on axis count alone.

Maintenance sources broadly recommend daily, weekly, monthly, and annual tasks, with deeper inspections and software updates at longer intervals. CNC.works and LMW outline daily cleaning and fluid checks, weekly lubrication and wiring inspections, monthly filter maintenance, and annual comprehensive checks. Baker Industries and SW Machine Tech add that calibration of tools and machines should follow a defined schedule using approved reference standards, with detailed documentation. The exact interval depends on machine type, duty cycle, and quality requirements, but consistency and recordŌĆækeeping matter more than any one calendar rule.

Precision CNC machining centers are only as reliable as the systems wrapped around them. A rigid machine and fast spindle mean little without disciplined programming, trained operators, structured maintenance, stable electrical conditions, and tight quality control. When those pieces are aligned, the CNC system becomes a predictable, longŌĆælived asset that converts clean power and good code into accurate metal parts, shift after shift.

Leave Your Comment